<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Max Dehn, 1878

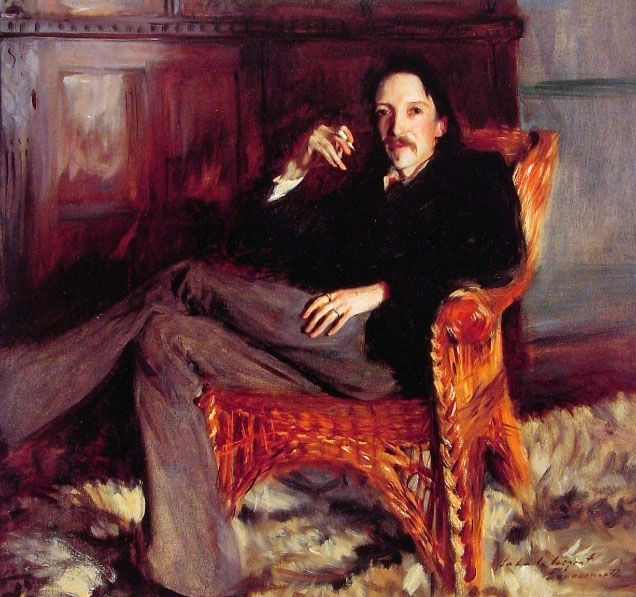

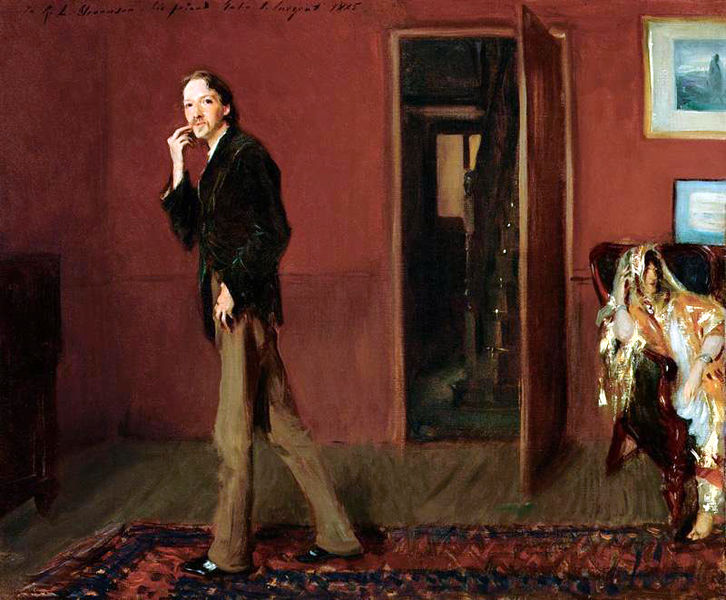

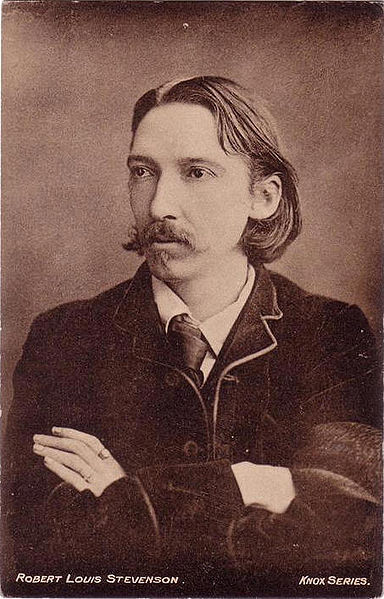

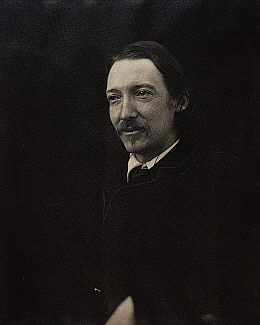

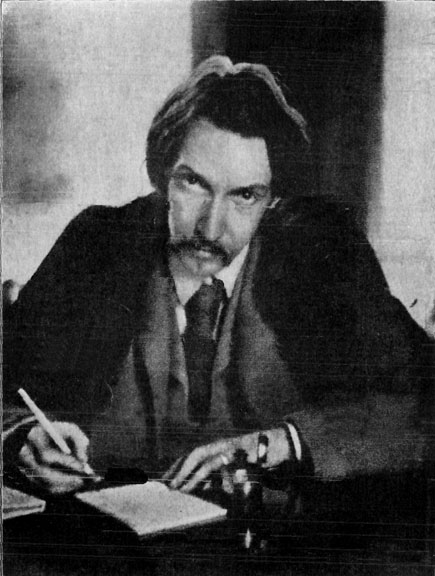

- Novelist Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson, 1850

- Emperor of China Jiaqing, 1760

PAGE SPONSOR

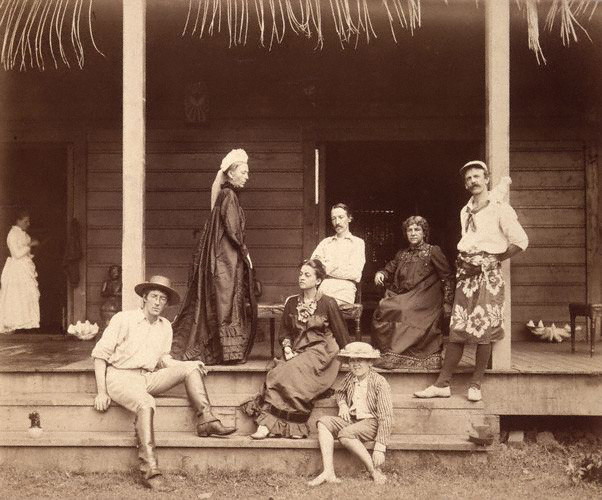

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer. Stevenson has been greatly admired by many authors, including Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, Rudyard Kipling, Marcel Schwob, Vladimir Nabokov, J.M. Barrie, and G.K. Chesterton, who said of him that he "seemed to pick the right word up on the point of his pen, like a man playing spillikins".

Stevenson was born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson at 8 Howard Place, Edinburgh, Scotland, on 13 November 1850, to Thomas Stevenson (1818 – 1887), a leading lighthouse engineer, and his wife, the former Margaret Isabella Balfour (1829 – 1897). Lighthouse design was the family profession: Thomas's own father was the famous Robert Stevenson, and his maternal grandfather, Thomas Smith, and brothers Alan and David were also among those in the business. On Margaret's side, the family were gentry, tracing their name back to an Alexander Balfour, who held the lands of Inchrye in Fife in the fifteenth century. Her father, Lewis Balfour (1777 – 1860), was a minister of the Church of Scotland at nearby Colinton, and Stevenson spent the greater part of his boyhood holidays in his house. "Now I often wonder", says Stevenson, "what I inherited from this old minister. I must suppose, indeed, that he was fond of preaching sermons, and so am I, though I never heard it maintained that either of us loved to hear them." Both Balfour and his daughter had a "weak chest" and often needed to stay in warmer climates for their health. Stevenson inherited a tendency to coughs and fevers, exacerbated when the family moved to a damp and chilly house at 1 Inverleith Terrace in 1853. The family moved again to the sunnier 17 Heriot Row when Stevenson was six, but the tendency to extreme sickness in winter remained with him until he was eleven. Illness would be a recurrent feature of his adult life, and left him extraordinarily thin. Contemporary views were that he had tuberculosis, but more recent views are that it was bronchiectasis or even sarcoidosis. Stevenson's parents were both devout and serious Presbyterians, but the household was not incredibly strict. His nurse, Alison Cunningham (known as Cummy), was more fervently religious. Her Calvinism and folk beliefs were an early source of nightmares for the child; and he showed a precocious concern for religion. But she also cared for him tenderly in illness, reading to him from Bunyan and the Bible as he lay sick in bed, and telling tales of the Covenanters. Stevenson recalled this time of sickness in the poem "The Land of Counterpane" in A Child's Garden of Verses (1885) and dedicated the book to his nurse.

An

only child, strange-looking and eccentric, Stevenson found it hard to

fit in when he was sent to a nearby school at six, a pattern repeated

at eleven, when he went on to the Edinburgh Academy; but he mixed well in lively games with his cousins in summer holidays at the Colinton manse. In

any case, his frequent illnesses often kept him away from his first

school, and he was taught for long stretches by private tutors. He was

a late reader, first learning at seven or eight; but even before this

he dictated stories to his mother and nurse. Throughout

his childhood he was compulsively writing stories. His father was proud

of this interest: he had himself written stories in his spare time

until his own father found them and told him to "give up such nonsense

and mind your business". He

paid for the printing of Robert's first publication at sixteen, an

account of the covenanters' rebellion, published on its two hundredth

anniversary, The Pentland Rising: a Page of History, 1666 (1866). It was expected that Stevenson's writing would remain a sideline; and in November 1867 he entered the University of Edinburgh to

study engineering. He showed from the start no enthusiasm for his

studies and devoted much energy to avoiding lectures. This time was

more important for the friendships he made: with other students in the Speculative Society (an

exclusive debating club), particularly with Charles Baxter, who would

become Stevenson's financial agent; and with one professor, Fleeming Jenkin, whose house staged amateur drama in which Stevenson took part, and whose biography he would later write. Perhaps

most important at this point in his life was a cousin, Robert Alan

Mowbray Stevenson (known as "Bob"), a lively and light-hearted young

man, who instead of the family profession had chosen to study art. Each year during vacations, Stevenson travelled to inspect the family's engineering works – to Anstruther and Wick in 1868, with his father on his official tour of Orkney and Shetland islands lighthouses in 1869, for three weeks to the island of Earraid in

1870. He enjoyed the travels, but more for the material they gave for

his writing than for any engineering interest: the voyage with his

father pleased him because a similar journey of Walter Scott with Robert Stevenson had provided the inspiration for The Pirate. In

April 1871, he announced to his father his decision to pursue a life of

letters. Though the elder Stevenson was naturally disappointed, the

surprise cannot have been great, and Stevenson's mother reported that

he was "wonderfully resigned" to his son's choice. To provide some

security, it was agreed that Stevenson should read Law (again at

Edinburgh University) and be called to the Scottish bar. Years later, in his poetry collection Underwoods (1887), he looked back on how he turned away from the family profession. In other respects too, Stevenson was moving away from his upbringing. His dress became more Bohemian:

he already wore his hair long, but he now took to wearing a velveteen

jacket and rarely attended parties in conventional evening dress. Within the limits of a strict allowance, he visited cheap pubs and brothels. More

importantly, he had come to reject Christianity. In January 1873, his

father came across the constitution of the LJR (Liberty, Justice,

Reverence) club of which Stevenson with his cousin Bob was a member,

which began "Disregard everything our parents have taught us".

Questioning his son about his beliefs, he discovered the truth, leading

to a long period of dissension with both parents: What a damned curse

I am to my parents! as my father said "You have rendered my whole life

a failure". As my mother said "This is the heaviest affliction that has

ever befallen me". O Lord, what a pleasant thing it is to have damned

the happiness of (probably) the only two people who care a damn about

you in the world. In late 1873, on a visit to a cousin in England, Stevenson made two new friendships that were to be of great importance to him, Sidney Colvin and

Fanny (Frances Jane) Sitwell. Sitwell was a woman of thirty four, with

a young son, separated from her husband. She attracted the devotion of

many who met her, including Colvin, who eventually married her in 1901.

Stevenson was another of those drawn to her, and over several years

they kept up a heated correspondence, in which Stevenson wavered

between the role of a suitor and a son (he came to address her as

"Madonna"). Colvin

became Stevenson's literary adviser, and after his death was the first

editor of his letters. Soon after their first meeting he had placed

Stevenson's first paid contribution, an essay, "Roads", in The Portfolio. Stevenson was soon active in London literary life, becoming acquainted with many of the writers of the time, including Andrew Lang, Edmund Gosse, and Leslie Stephen, the editor of the Cornhill Magazine,

who took an interest in Stevenson's work. Stephen in turn would

introduce him to a more important friend: visiting Edinburgh in 1875,

he took Stevenson with him to visit a patient at the Edinburgh Infirmary, William Henley.

Henley, an energetic and talkative man with a wooden leg, became a

close friend and occasional literary collaborator for many years, until

in 1888 a quarrel broke up the friendship. He is often seen as

providing a partial model for the character of Long John Silver in Treasure Island. In November 1873, Stevenson had a physical collapse and was sent for his health to Menton on the French Riviera.

He returned in better health in April 1874, and settled down to his

studies, but he would often return to France in the coming years. He made long and frequent trips to the neighbourhood of the Forest of Fontainebleau, staying at Barbizon, Grez-sur-Loing and Nemours, becoming a member of the artists' colonies there, as well as to Paris to visit galleries and the theatres. He

did qualify for the Scottish bar in July 1875; and his father added a

brass plate with "R.L. Stevenson, Advocate" to the Heriot Row house.

But although his law studies would influence his books, he never

practised law. All

his energies were now in travel and writing. One of his journeys, a

canoe voyage in Belgium and France with Sir Walter Simpson, a friend

from the Speculative Society and frequent travel companion, was the

basis of his first real book, An Inland Voyage (1878). The canoe voyage with Simpson brought Stevenson to Grez in September 1876; and here he first met Fanny Vandegrift Osbourne (1840 – 1914). Born in Indianapolis,

she had married at the age of seventeen and soon moved with her

husband, Samuel Osbourne, to California. She had three children by the

marriage, Isobel, the eldest, Lloyd and

Hervey (who died in 1875); but anger over infidelities by her husband

led to a number of separations and in 1875 she had taken her children

to France, where she and Isobel studied art. Although

Stevenson returned to Britain shortly after this first meeting, Fanny

apparently remained in his thoughts, and he wrote an essay "On falling

in love" for the Cornhill Magazine. They met again early in 1877 and became lovers. Stevenson spent much of the following years with her and her children in France. Then, in August 1878, Fanny returned to her home in San Francisco, California. Stevenson at first remained in Europe, making the walking trip that would form the basis for Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879);

but in August 1879, he set off to join her, against the advice of his

friends and without notifying his parents. He took second class passage

on the steamship Devonia, in part to save money, but also to learn how others travelled and to increase the adventure of the journey. From New York City he travelled overland by train to California. He later wrote about the experience in The Amateur Emigrant. Although it was good experience for his literature, it broke his health, and he was near death when he arrived in Monterey. He was nursed back to health by some ranchers there. By

December 1879 he had recovered his health enough to continue to San

Francisco, where for several months he struggled "all alone on

forty-five cents a day, and sometimes less, with quantities of hard

work and many heavy thoughts," in

an effort to support himself through his writing, but by the end of the

winter his health was broken again, and he found himself at death's

door. Vandegrift — now divorced and recovered from her own illness —

came to Stevenson's bedside and nursed him to recovery. "After a

while," he wrote, "my spirit got up again in a divine frenzy, and has

since kicked and spurred my vile body forward with great emphasis and

success." When his father heard of his condition he cabled him money to help him through this period. In

May 1880, Stevenson married Fanny although, as he said, he was "a mere

complication of cough and bones, much fitter for an emblem of mortality

than a bridegroom." With his new wife and her son, Lloyd, he travelled north of San Francisco to Napa Valley, and spent a summer honeymoon at an abandoned mining camp on Mount Saint Helena. He wrote about this experience in The Silverado Squatters. He met Charles Warren Stoddard, co-editor of the Overland Monthly and author of South Sea Idylls, who

urged Stevenson to travel to the south Pacific, an idea which would

return to him many years later. In August 1880 he sailed with his

family from New York back to Britain, and found his parents and his

friend Sidney Colvin on the wharf at Liverpool,

happy to see him return home. Gradually his new wife was able to patch

up differences between father and son and make herself a part of the

new family through her charm and wit. For

the next seven years, between 1880 and 1887, Stevenson searched in vain

for a place of residence suitable to his state of health. He spent his

summers at various places in Scotland and England, including Westbourne, Dorset, a residential area in Bournemouth. There he lived in a dwelling he renamed Skerryvore after a lighthouse, the tallest in Scotland, built by his uncle Alan Stevenson many years earlier. For his winters, he escaped to sunny France, and lived at Davos-Platz and the Chalet de Solitude at Hyeres,

where, for a time, he enjoyed almost complete happiness. "I have so

many things to make life sweet for me," he wrote, "it seems a pity I

cannot have that other one thing — health. But though you will be angry

to hear it, I believe, for myself at least, what is is best. I believed

it all through my worst days, and I am not ashamed to profess it now." In spite of his ill health he produced the bulk of his best known work during these years: Treasure Island, his first widely popular book; Kidnapped; Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the story which established his wider reputation; and two volumes of verse, A Child's Garden of Verses and Underwoods. At Skerryvore he gave a copy of Kidnapped to his dear friend and frequent visitor, Henry James. On

the death of his father in 1887, Stevenson felt free to follow the

advice of his physician to try a complete change of climate. He started

with his mother and family for Colorado; but after landing in New York they decided to spend the winter at Saranac Lake, in the Adirondacks. During the intensely cold winter Stevenson wrote a number of his best essays, including Pulvis et Umbra, he began The Master of Ballantrae,

and lightheartedly planned, for the following summer, a cruise to the

southern Pacific Ocean. "The proudest moments of my life," he wrote,

"have been passed in the stern-sheets of a boat with that romantic

garment over my shoulders." In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht Casco and

set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel "plowed her

path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far

from any hand of help." The

salt sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health;

and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific,

visiting important island groups, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands where he became a good friend of King Kalākaua, with whom Stevenson spent much time. Furthermore, Stevenson befriended the king's niece, Princess Victoria Kaiulani, who was of Scottish heritage. He also spent time at the Gilbert Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand and the Samoan Islands. During this period he completed The Master of Ballantrae, composed two ballads based on the legends of the islanders, and wrote The Bottle Imp. He also witnessed the Samoan crisis. The experience of these years is preserved in his various letters and in The South Seas. A second voyage on the Equator followed in 1889 with Lloyd Osbourne accompanying them. It was also from this period that one particular open letter stands

as testimony to his activism and indignation at the pettiness of such

'powers that be' as a Presbyterian minister in Honolulu named Rev. Dr.

Hyde. During his time in the Hawaiian Islands, Stevenson had visited Molokai and the leper colony there, shortly after the demise of Father Damien. When Dr. Hyde wrote a letter to a fellow clergyman speaking ill of Father Damien, Stevenson wrote a scathing open letter of rebuke to Dr. Hyde. Soon afterwards in April 1890 Stevenson left Sydney on the Janet Nicoll and went on his third and final voyage among the South Seas islands. In 1890 he purchased four hundred acres (about 1.6 square kilometres) of land in Upolu,

one of the Samoan islands. Here, after two aborted attempts to visit

Scotland, he established himself, after much work, upon his estate in

the village of Vailima. Stevenson himself adopted the native name Tusitala (Samoan for

"Teller of Tales", i.e. a storyteller). His influence spread to the

Samoans, who consulted him for advice, and he soon became involved in

local politics. He was convinced the European officials appointed to

rule the Samoans were incompetent, and after many futile attempts to

resolve the matter, he published A Footnote to History.

This was such a stinging protest against existing conditions that it

resulted in the recall of two officials, and Stevenson feared for a

time it would result in his own deportation. When things had finally

blown over he wrote to Colvin, who came from a family of distinguished

colonial administrators, "I used to think meanly of the plumber; but

how he shines beside the politician!" He was friends with some of the politicians and their families. At one point he formally donated, by deed of gift, his birthday to the daughter of the American Land Commissioner Henry Clay Ide, since she was born on Christmas Day and

had no birthday celebration separate from the family's Christmas

celebrations. This led to a strong bond between the Stevenson and Ide

families. In

addition to building his house and clearing his land and helping the

Samoans in many ways, he found time to work at his writing. He felt

that "there was never any man had so many irons in the fire." He wrote The Beach of Falesa, Catriona (titled David Balfour in the USA), The Ebb-Tide, and the Vailima Letters, during this period. For

a time during 1894 Stevenson felt depressed; he wondered if he had

exhausted his creative vein and completely worked himself out. He wrote

that he had "overworked bitterly". He felt more clearly that, with each fresh attempt, the best he could write was "ditch-water". He

even feared that he might again become a helpless invalid. He rebelled

against this idea: "I wish to die in my boots; no more Land of

Counterpane for me. To be drowned, to be shot, to be thrown from a

horse — ay, to be hanged, rather than pass again through that slow

dissolution." He then suddenly had a return of his old energy and he began work on Weir of Hermiston. "It's so good that it frightens me," he is reported to have exclaimed.

He felt that this was the best work he had done. He was convinced,

"sick and well, I have had splendid life of it, grudge nothing, regret

very little ... take it all over, damnation and all, would hardly

change with any man of my time." Without knowing it, he was to have his wish fulfilled. During the morning of 3 December 1894, he had worked hard as usual on Weir of Hermiston.

During the evening, while conversing with his wife and straining to

open a bottle of wine, he suddenly exclaimed, "What's that!" He then

asked his wife, "Does my face look strange?" and collapsed beside her. He died within a few hours, probably of a cerebral haemorrhage,

at the age of 44. The Samoans insisted on surrounding his body with a

watch-guard during the night and on bearing their Tusitala upon their

shoulders to nearby Mount Vaea, where they buried him on a spot overlooking the sea. Stevenson had always wanted his 'Requiem' inscribed on his tomb. However, the piece is widely misquoted, including the inscription on his tomb, which closes: Stevenson was loved by the Samoans and the engraving on his tombstone was translated to a Samoan song of grief which is well known and still sung in Samoa.

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

And the hunter home from the hill.