<Back to Index>

- Surgeon William Beaumont, 1785

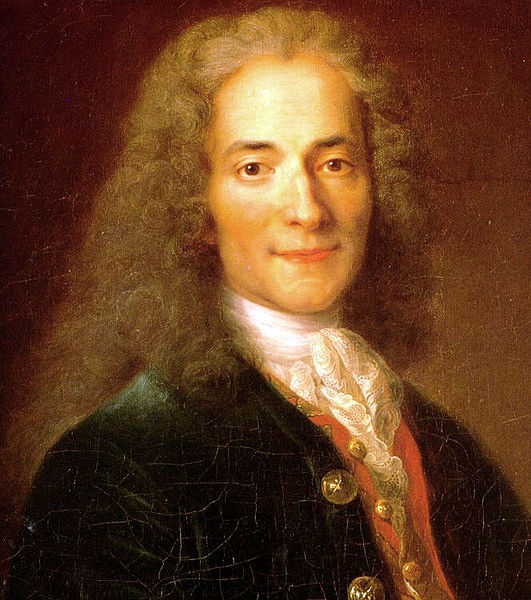

- Writer François Marie Arouet (Voltaire), 1694

- Member of the Politburo Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov, 1902

PAGE SPONSOR

François-Marie Arouet (21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778), better known by the pen name Voltaire, was a French Enlightenment writer and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion and free trade. Voltaire was a prolific writer and produced works in almost every literary form including plays, poetry, novels, essays, historical and scientific works, more than 20,000 letters and more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. He was an outspoken supporter of social reform, despite strict censorship laws and harsh penalties for those who broke them. As a satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma and the French institutions of his day.

Voltaire was one of several Enlightenment figures (along with Montesquieu, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau) whose works and ideas influenced important thinkers of both the American and French Revolutions. François Marie Arouet was born in Paris, the youngest of the five children (only three of which survived) of François Arouet (1650 – 1 January 1722), a notary who was a minor treasury official, and his wife, Marie Marguerite d'Aumart (ca. 1660 – 13 July 1701), from a noble family of the province of Poitou. Voltaire was educated by Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1704 – 1711), where he learned Latin and Greek; later in life he became fluent in Italian, Spanish and English. By

the time he left school, Voltaire had decided he wanted to be a writer,

against the wishes of his father who wanted him to become a lawyer.

Voltaire, pretending to work in Paris as an assistant to a lawyer, spent much of his time writing poetry. When his father found him out, he sent Voltaire to study law, this time in Caen (Normandy).

Nevertheless, he continued to write, producing essays and historical

studies that were not always noted for their accuracy, although most

were accurate. Voltaire's wit made him popular among some of the

aristocratic families with whom he mixed. His father then obtained a

job for him as a secretary to the French ambassador in the Netherlands, where Voltaire fell in love with a French refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer. Their scandalous elopement was foiled by Voltaire's father and he was forced to return to France. Most

of Voltaire's early life revolved around Paris. From early on, Voltaire

had trouble with the authorities for his energetic attacks on the

government and the Catholic Church. These activities were to result in numerous imprisonments and exiles. He allegedly wrote satirical verses about the aristocracy. A work about the Régent thought to be by him led to his imprisonment in the Bastille for eleven months, until the real author came forward. While there, he wrote his debut play, Œdipe. Its success established his reputation. The name "Voltaire", which the author adopted in 1718, is an anagram of "AROVET LI," the Latinized spelling of his surname, Arouet, and the initial letters of "le jeune" ("the younger"). The name also echoes in reverse order the syllables of the name of a family château in the Poitou region: "Airvault".

The adoption of the name "Voltaire" following his incarceration at the

Bastille is seen by many to mark Voltaire's formal separation from his

family and his past. Richard Holmes supports

this derivation of the name, but adds that a writer such as Voltaire

would have intended it to also convey its connotations of speed and

daring. These come from associations with words such as "voltige" (acrobatics on a trapeze or horse), "volte-face" (a spinning about to face one's enemies), and "volatile"

(originally, any winged creature). "Arouet" was not a noble name fit

for his growing reputation, especially given that name's resonance with

"à rouer" ("for thrashing") and "roué" (a "débauché"). Voltaire is known to have used at least 178 separate pen names during his lifetime. The

aptitude for quick, perceptive, cutting, witty and often scathingly

critical repartee for which Voltaire is known today made him highly

unpopular with many of his contemporaries, including much of the French aristocracy. These sharp-tongued retorts were responsible for Voltaire's exile from France, during which he resided in Great Britain. After

Voltaire retorted to an insult given him by the young French nobleman

Chevalier de Rohan in late 1725, the aristocratic Rohan family obtained

a royal lettre de cachet, an irrevocable and often arbitrary penal decree signed by the French King (Louis XV, in the time of Voltaire) that was often bought by members of the wealthy nobility to dispose of undesirables. They then used this warrant to force Voltaire first into imprisonment in the Bastille and then into exile without holding a trial or giving him an opportunity to defend himself. The incident marked the beginning of Voltaire's attempts to improve the French judicial system. Voltaire's

exile in Great Britain lasted over two years, and his experiences there

greatly influenced many of his ideas. The young man was impressed by

Britain's constitutional monarchy in contrast to the French absolute monarchy,

as well as the country's support of the freedoms of speech and

religion. He was also influenced by several of the neoclassical writers

of the age, and developed an interest in earlier English literature,

especially the works of Shakespeare,

still little known in continental Europe at the time. Despite pointing

out his deviations from neoclassical standards, Voltaire saw

Shakespeare as an example French writers might look up to, since drama

in France, despite being more polished, lacked on-stage action. Later,

however, as Shakespeare's influence was being increasingly felt in

France, Voltaire would endeavour to set a contrary example with his own

plays, decrying what he considered Shakespeare's barbarities. After

almost three years in exile, Voltaire returned to Paris and published

his views on British attitudes towards government, literature, and

religion in a collection of essays in letter form entitled the Lettres philosophiques sur les Anglais (Philosophical Letters on the English).

Because he regarded the British constitutional monarchy as more

developed and more respectful of human rights (particularly religious

tolerance) than its French counterpart, these letters met great

controversy in France, to the point where copies of the document were

burnt and Voltaire was again forced to leave France. Voltaire's next destination was the Château de Cirey, located on the borders of Champagne and Lorraine.

The building was renovated with his money, and here he began a

relationship with the Marquise du Châtelet, Gabrielle

Émilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil (famous in her own right as Émilie du Châtelet). Cirey was owned by the Marquise's husband, Marquis Florent-Claude du Chatelet,

who sometimes visited his wife and her lover at the chateau. The

relationship, which lasted for fifteen years, had a significant

intellectual element. Voltaire and the Marquise collected over 21,000

books, an enormous number for the time. Together, they studied these

books and performed experiments in the "natural sciences" in his laboratory. Voltaire's experiments included an attempt to determine the elements of fire. Having

learned from his previous brushes with the authorities, Voltaire began

his future habit of keeping out of personal harm's way, and denying any

awkward responsibility. He continued to write many plays, such as Mérope (or

"La Mérope française") and began his long researches into

science and history . Again, a main source of inspiration for Voltaire

were the years of his British exile, during which he had been strongly

influenced by the works of Sir Isaac Newton. Voltaire strongly believed in Newton's theories, especially concerning optics (Newton’s discovery that white light is composed of all the colours in the spectrum led

to many experiments at Cirey), and gravity (Voltaire is the source of

the famous story of Newton and the apple falling from the tree, which

he had learned from Newton's niece in London and first mentioned in his Essai sur la poésie épique, or Essay on Epic Poetry). Although both Voltaire and the Marquise were curious about the philosophies of Gottfried Leibniz,

a contemporary and rival of Newton, they remained essentially

"Newtonians", despite the Marquise's adoption of certain aspects of

Leibniz's arguments against Newton. She translated Newton's Latin Principia in

full, adjusting a few errors along the way, and hers remained the

definitive French translation well into the 20th century. Voltaire's

book Eléments de la philosophie de Newton (Elements

of Newton's Philosophy), which was probably co-written with the

Marquise, made Newton accessible to a far greater public. It is often

considered the work that finally brought about general acceptance of

Newton's optical and gravitational theories. Voltaire

and the Marquise also studied history — particularly those persons who

had contributed to civilization. Voltaire's second essay in English had

been Essay upon the Civil Wars in France. It was followed by La Henriade,

an epic poem on the French king Henri IV, glorifying his attempt to end

the Catholic-Protestant massacres with the Edict of Nantes, and by a

historical novel on King Charles XII of Sweden. These, along with his Letters on England mark

the beginning of Voltaire's open criticism of intolerance and

established religions. Voltaire and the Marquise also worked with

philosophy, particularly with metaphysics, the branch that dealt with what could not be directly proven: whether or not there was a God, etc. Voltaire and the Marquise analyzed the Bible, trying to discover its validity in their time. Voltaire's critical views on religion are reflected in his belief in separation of church and state and religious freedom, ideas that he had formed after his stay in England. Though

deeply committed to the Marquise, Voltaire by 1744 found life at the

château confining. On a visit to Paris that year, he found a new

love: his niece. At first, his attraction to Marie Louise Mignot was clearly sexual, as evidenced by his letters to her (only discovered in 1937). Much

later, they lived together, perhaps platonically, and remained together

until Voltaire's death. Meanwhile, the Marquise also took a lover, the

Marquis de Saint-Lambert.

After the death of the Marquise in childbirth in September 1749, Voltaire briefly returned to Paris and in 1750 moved to Potsdam to join Frederick the Great, a close friend and admirer of his. The

king had repeatedly invited him to his palace, and now gave him a

salary of 20,000 francs a year. Though life went well at first — in 1752

he wrote Micromégas, perhaps the first piece of science fiction involving

ambassadors from another planet witnessing the follies of humankind — his

relationship with Frederick the Great began to deteriorate and he

encountered other difficulties. An argument with Maupertuis, the president of the Berlin Academy of Science, provoked Voltaire's Diatribe du docteur Akakia (Diatribe

of Doctor Akakia), which satirized some of Maupertuis' theories and his

abuse of power in his persecutions of a mutual acquaintance, Samuel

Koënig. This greatly angered Frederick, who had all copies of the

document burned and arrested Voltaire at an inn where he was staying

along his journey home. Voltaire headed toward Paris, but Louis XV banned him from the city, so instead he turned to Geneva, near which he bought a large estate (Les Délices). Though he was received openly at first, the law in Geneva which banned theatrical performances and the publication of The Maid of Orleans against his will made him move at the end of 1758 out of Geneva across the French border to Ferney, where he had bought an even larger estate, and led to Voltaire's writing of Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism) in 1759. This satire on Leibniz's

philosophy of optimistic determinism remains the work for which

Voltaire is perhaps best known. He would stay in Ferney for most of the

remaining 20 years of his life, frequently entertaining distinguished

guests, like James Boswell, Giacomo Casanova, and Edward Gibbon. In 1764 he published his most important philosophical work, the Dictionnaire Philosophique, a series of articles mainly on Christian history and dogmas, a few of which were originally written in Berlin.

From 1762 he began to champion unjustly persecuted people, the case of Jean Calas being the most celebrated. This Huguenot merchant had been tortured to death in 1763, supposedly because he had murdered

his son for wanting to convert to Catholicism. His possessions were

confiscated and his remaining children were taken from his widow and

were forced to become members of a monastery. Voltaire, seeing this as

a clear case of religious persecution, managed to overturn the

conviction in 1765.

In

February 1778, Voltaire returned for the first time in 20 years to

Paris, among other reasons to see the opening of his latest tragedy, Irene.

The 5-day journey was too much for the 83-year old, and he believed he

was about to die on February 28, writing "I die adoring God, loving my

friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition." However,

he recovered, and in March saw a performance of Irene where he was treated by the audience as a returning hero. However,

he soon became ill again and died on 30 May 1778. When asked on his

deathbed by a priest to renounce the devil and turn to God, he is

alleged to have replied, "For God's sake, let me die in peace." Because

of his well-known criticism of the church, which he had refused to

retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial, but

friends managed to bury his body secretly at the abbey of

Scellières in Champagne before this prohibition had been announced. His heart and brain were embalmed separately. On 11 July 1791, the National Assembly, which regarded him as a forerunner of the French revolution, had his remains brought back to Paris to enshrine him in the Panthéon.

It is estimated that a million people attended the procession, which

stretched throughout Paris. There was an elaborate ceremony, complete

with an orchestra, and the music included a piece that André Grétry composed

specially for the event, which included a part for the "tuba curva".

This was an instrument that originated in Roman times as the cornu but had been recently revived under a new name. A

widely-repeated story that the remains of Voltaire were stolen by

religious fanatics in 1814 or 1821 during the Pantheon restoration and

thrown into a garbage heap is false. Such rumours resulted in the

coffin being opened in 1897, which confirmed that his remains were

still present.