<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Erasmus Reinhold, 1511

- Industrial Designer Harley J. Earl, 1893

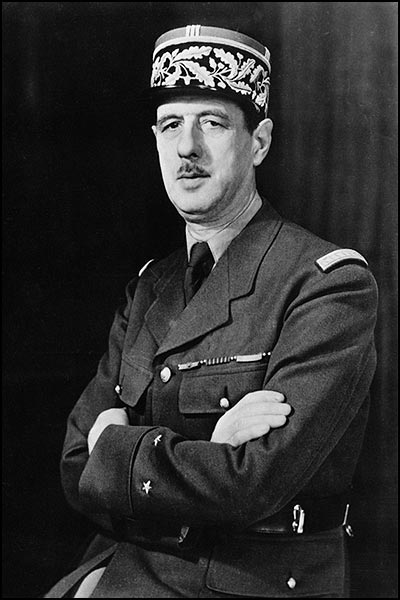

- Président de la République Française Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle, 1890

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 1890 – 9 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969.

A veteran of World War I,

in the 1920s and 1930s de Gaulle came to the fore as a proponent of

armoured warfare and advocate of military aviation, which he considered

a means to break the stalemate of trench warfare. During World War II, he reached the temporary rank of Brigadier General, leading one of the few successful armoured counter-attacks during the 1940 Fall of France,

and then briefly served in the French government as France was falling.

He escaped to England and gave a famous radio address in June 1940,

exhorting the French people to resist Nazi Germany and organised the Free French Forces with exiled French officers in Britain. He

gradually obtained control of all French colonies - most of which had

at first been controlled by the pro-German Vichy regime - and by the

time of the liberation of France in 1944 he was heading a government in

exile, insisting that France be treated as an independent great power

by the other Allies. De Gaulle became prime minister in the French Provisional Government, resigning in 1946 due to political conflicts. After

the war he founded his own political party, the RPF. Although he

retired from politics in the early 1950s after the RPF's failure to win

power, he was voted back to power as prime minister by the French Assembly during the May 1958 crisis. De Gaulle led the writing of a new constitution founding the Fifth Republic, and was elected President of France, an office which now held much greater power than in the Third and Fourth Republics. As

President, Charles de Gaulle ended the political chaos that preceded

his return to power. A new French currency was issued in January 1960

to control inflation and industrial growth was promoted. Although he

initially supported French rule over Algeria,

he controversially decided to grant independence to that country,

ending an expensive and unpopular war but leaving France divided and

having to face down opposition from the white settlers and French

military who had originally supported his return to power. De

Gaulle oversaw the development of French atomic weapons and promoted a

pan-European foreign policy, seeking independence from U.S. and British

influence. He withdrew France from NATO military command - although remaining a member of the western alliance - and twice vetoed Britain's entry into the European Community. He travelled widely in Eastern Europe and other parts of the world and recognised Communist China. On a visit to Canada he gave encouragement to Quebec Separatism. During his term, de Gaulle also faced controversy and political opposition from Communists and Socialists. Despite having been re-elected as President, this time by direct popular ballot, in 1965, in May 1968 he

appeared likely to lose power amidst widespread protests by students

and workers, but survived the crisis with an increased majority in the

Assembly. However, de Gaulle resigned after losing a referendum in

1969. He is considered by many to be the most influential leader in

modern French history. De Gaulle was born in the industrial region of Lille in French Flanders, the second of five children of Henri de Gaulle, a professor of philosophy and literature at a Jesuit college, who eventually founded his own school. He was raised in a family of devout Roman Catholics who were nationalist and traditionalist, but also quite progressive. De Gaulle's father, Henri, came from a long line of aristocrats from Normandy and Burgundy, while his mother, Jeanne Maillot, descended from a family of rich entrepreneurs from Lille. According to Henri, the family's true origin was never determined, but could have been Celtic or Flemish. He thought that the name could be derived from the word gaule — a long pole which was used in the Middle Ages to beat olives from the trees. Another source has the name deriving from Galle, meaning "oak" in the Gaulish language, and the sacred tree of the druids. Since de Gaulle's family hailed from French Flanders, the name could also be a francisised form of the common Dutch Van de walle meaning From the moat. De Gaulle was educated in Paris at the College Stanislas and also briefly in Belgium. Since childhood, he had displayed a keen interest in reading and studying history. Choosing a military career, de Gaulle spent four years studying and training at the elite military academy, Saint-Cyr. While there, and because of his height, high forehead, and nose, he acquired the nicknames of "the great asparagus" and "Cyrano". He acquired yet another nickname, Le Connétable, when he was a prisoner of war in Germany during the Great War.

This had come about because of the talks which he gave to fellow

prisoners on the progress of the conflict. These were delivered with

such patriotic ardour and confidence in victory that they called him by

the title which had been given to the commander-in-chief of the French

army during the monarchy. Graduating from St Cyr in 1912, he joined the 33rd infantry regiment of the French Army, based at Arras and commanded by Colonel (and future Marshal) Pétain. While serving during World War I,

he reached the rank of captain, commanding a company. He was wounded

several times, one of them in the left hand, as a result of which he

wore his wedding ring on his right hand in later life. He was captured

at Douaumont in the Battle of Verdun in March 1916. While being held as a prisoner of war by the German Army, de Gaulle wrote his first book, co-written by Matthieu Butler, "L'Ennemi et le vrai ennemi" (The Enemy and the True Enemy), analyzing the issues and divisions within the German Empire and its forces; the book was published in 1924. After the armistice, de Gaulle continued to serve in the army and on the staff of General Maxime Weygand's military mission to Poland during its war with Communist Russia (1919–1921), working as an instructor to Polish infantry forces. He distinguished himself in operations near the River Zbrucz and won the highest Polish military decoration, the Virtuti Militari. He was promoted to Commandant in the Polish Army and offered a further career in Poland, but chose instead to return to France, where he taught at the École Militaire, becoming a protégé of his old commander, Marshal Philippe Pétain. De

Gaulle was heavily influenced by the use of tanks and rapid maneuvers

rather than trench warfare. De Gaulle served with the Army of

Occupation in the Rhineland in the mid 1920s. He also — as a Commandant (Major)

by the late 1920s - briefly commanded a light infantry battalion at

Treves and then served a tour of duty in Syria, then a French colony.

During the 1930s, now a lieutenant-colonel, he served as a staff

officer in France. At the outbreak of World War II, de Gaulle was only a colonel,

having antagonized the leaders of the military through the 1920s and

1930s with his bold views. Initially commanding a tank regiment in the

French 5th Army, de Gaulle implemented many of his theories and tactics

for armoured warfare. After the German breakthrough at Sedan on 15 May 1940 he was given command of the 4th Armoured Division. On 17 May, de Gaulle attacked German tank forces at Montcornet with 200 tanks but no air support; on 28 May, de Gaulle's tanks forced the German infantry to retreat to Caumont — some

of the few tactical successes the French enjoyed while suffering

defeats across the country. De Gaulle was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, which he would hold for the rest of his life. On 6 June, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud appointed him Under Secretary of State for National Defence and War and put him in charge of coordination with the United Kingdom. As

a junior member of the French government, he unsuccessfully opposed

surrender, advocating instead that the government remove itself to

North Africa and carry on the war as best it could from France's

African colonies. While serving as a liaison with the British

government, de Gaulle telephoned Paul Reynaud, the French prime

minister, from London on 16 June informing him of the offer by Britain

of a Declaration of Union. This

would have in effect merged France and the United Kingdom into a single

country, with a single government and a single army for the duration of

the war. This was a desperate last-minute effort to strengthen the

resolve of those members of the French government who were in favor of

fighting on. The man behind the offer of a declaration of union was Jean Monnet, who was based in London as President of the Franco-British Committee of Co-operation. Monnet had first sought the advice of Desmond Morton, Churchill's Personal Assistant, who suggested that the proposal be put to Churchill through Neville Chamberlain.

The latter interceded with Churchill and the idea was put before the

Cabinet, where it was approved. The final document was drafted by Robert Vansittart, Permanent Secretary to the Foreign Office, in conjunction with Monnet himself, Morton, Sir Arthur Salter, MP for Oxford University, and Monnet's deputy at the Franco-British Committee of Co-operation, René Pleven. When

the proposal was put before Churchill, he was initially unenthusiastic.

However, de Gaulle managed to convince him that "some dramatic move was

essential to give Reynaud the support which he needed to keep his

Government in the war". Yet

despite his endorsement of the extraordinary proposal at the time, de

Gaulle later sought to distance himself from it. During an interview in

1964, which was reported in Paris Match shortly

after the general's death, de Gaulle had remarked that he and Churchill

had tried to improvise something but that neither of them had any

illusions. It had been a myth, like other myths, dreamed up by Jean

Monnet. This report brought an instant rebuttal from Monnet, who

insisted that he had personally informed de Gaulle of the proposition

and that the latter had simply acquiesced, albeit with great

hesitation. De Gaulle's intervention in the matter had been later.

Returning the same day to Bordeaux,

the temporary wartime capital, de Gaulle learned that Marshal

Pétain had become prime minister and was planning to seek an armistice with

Nazi Germany. De Gaulle and allied officers rebelled against the new

French government; on the morning of 17 June, de Gaulle and other

senior French officers fled the country with 100,000 gold francs in

secret funds provided to him by the ex-prime minister Paul Reynaud.

Narrowly escaping the Luftwaffe, he landed safely in London that

afternoon. De Gaulle strongly denounced the French government's

decision to seek peace with the Nazis and set about building the Free French Forces out

of the soldiers and officers who were deployed outside France and in

its colonies or had fled France with him. On 18 June, de Gaulle

delivered a famous radio address via the BBC Radio service. Although the British cabinet initially attempted to block the speech, they were overruled by Churchill. De Gaulle's Appeal of 18 June exhorted the French people to not be demoralised and to continue to resist the occupation of France and work against the Vichy regime,

which had signed an armistice with Nazi Germany. Although the original

speech could only be heard in a few parts of occupied France, de

Gaulle's subsequent ones reached many parts of the territories under

the Vichy regime, helping to rally the French resistance movement and

earning him much popularity amongst the French people and soldiers. On

4 July 1940, a court-martial in Toulouse sentenced de Gaulle in absentia to four years in prison. At a second court-martial on 2 August 1940 de Gaulle was condemned to death for treason against the Vichy regime.

With British support, de Gaulle settled himself in Berkhamstead (36

miles northwest of London) and began organising the Free French forces.

Gradually, the Allies gave increasing support and recognition to de

Gaulle's efforts. In dealings with his British allies and the United States,

de Gaulle insisted at all times on retaining full freedom of action on

behalf of France, and he was constantly on the verge of being cut off

by the Allies. He harbored a suspicion of the British in particular,

believing that they were surreptitiously seeking to steal France's

colonial possessions in the Levant. Clementine Churchill,

who admired de Gaulle, once cautioned him, "General, you must not hate

your friends more than you hate your enemies." De Gaulle himself stated

famously, "France has no friends, only interests." The

situation was nonetheless complex, and de Gaulle's mistrust of both

British and U.S. intentions with regards to France was mirrored in

particular by a mistrust of the Free French among the U.S. political

leadership, who for a long time refused to recognise de Gaulle as the

representative of France, preferring to deal with representatives of

the Vichy government. Roosevelt in particular hoped that it would be

possible to wean Pétain away from Germany. Working with the French resistance and supporters in France's colonial African possessions after the Anglo-U.S. invasion of North Africa in November 1942, de Gaulle moved his headquarters to Algiers in May, 1943. He became first joint head (with the less resolutely independent General Henri Giraud,

the candidate preferred by the U.S. who wrongly suspected de Gaulle of

being a British puppet) and then - after squeezing out Giraud by force

of personality - sole chairman of the French Committee of National Liberation. At the liberation of France following Operation Overlord, he quickly established the authority of the Free French Forces in France, avoiding an Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories. He flew into France from the French colony of Algeria a

few days before the liberation of Paris by Leclerc's French Armoured

Division, and drove near the front of the liberating forces into the

city alongside Allied officials. De Gaulle made a famous speech

emphasising the role of France's people in her liberation. After his return to Paris, he moved back into his office at the War Ministry, thus proclaiming continuity of the Third Republic and denying the legitimacy of the Vichy regime. Under

the leadership of General de Lattre de Tassigny France fielded an

entire army - a joint force of Free French together with French

colonial troops from North Africa - on the western front. Initially

landing as part of Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France, the French First Army helped

to liberate almost one third of the country and meant that France

actively rejoined the Allies in the struggle against Germany. The

French First Army captured a large section of territory in southern

Germany after the Rhine crossings, thus enabling France to be an active

participant in the signing of the German surrender. Also, through the

intervention of the British and Americans at Yalta and despite the resistance of the Russians, a French zone of occupation was created in Germany.

De Gaulle served as President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic starting in September, 1944 and visiting Moscow for talks with Stalin at the end of 1944. He sent the French Far East Expeditionary Corps to re-establish French sovereignty in French Indochina in 1945. He made Admiral d'Argenlieu High commissioner of French Indochina and General Leclerc commander-in-chief in French Indochina and commander of the expeditionary corps. De

Gaulle finally resigned on 20 January 1946, complaining of conflict

between the political parties, and disapproving of the draft

constitution for the Fourth Republic, which he believed placed too much power in the hands of a parliament with its shifting party alliances. He was succeeded by Félix Gouin (French Section of the Workers' International, SFIO), then Georges Bidault (Popular Republican Movement, MRP) and finally Léon Blum (SFIO). De

Gaulle's opposition to the proposed constitution failed as the parties

of the left supported a parliamentary regime. The second draft

constitution narrowly approved at the referendum of October 1946 was even less to de Gaulle's liking than the first. He then returned to his home at Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises to write his war memoirs. In April 1947 de Gaulle made a renewed attempt to transform the political scene by creating a Rassemblement du Peuple Français (Rally of the French People, or RPF), but after initial success the movement lost momentum. In May 1953, he withdrew again from active politics, though the RPF lingered until September 1955. He once more retired to his country home to continue his war memoirs, Mémoires de guerre. The

famous opening paragraph of this work begins by declaring, "All my

life, I have had a certain idea of France (une certaine idée de

la France)", comparing his country to an old painting of a Madonna, and

ends by declaring that, given the divisive nature of French politics,

France cannot truly live up to this ideal without a policy of

"grandeur" (roughly "greatness"). During this period of formal

retirement, however, de Gaulle maintained regular contact with past

political lieutenants from wartime and RPF days, including sympathisers involved in political developments in French Algeria. The Fourth Republic was tainted by political instability, failures in Indochina and inability to resolve the Algerian question. It did, however, pass the 1956 loi-cadre Deferre which granted independence to Tunisia and Morocco, while the Premier Pierre Mendès-France put an end to the Indochina War through the Geneva Conference of 1954. On

13 May 1958, settlers seized the government buildings in Algiers,

attacking what they saw as French government weakness in the face of

demands among the Arab majority for Algerian independence. A "Committee

of Civil and Army Public Security" was created under the presidency of

General Jacques Massu, a Gaullist sympathiser. General Raoul Salan,

Commander-in-Chief in Algeria, announced on radio that he was assuming

provisional power, and appealed for "confidence in the Army and its

leaders". Under the pressure of Massu, Salan declared Vive de Gaulle! from the balcony of the Algiers Government-General building on 15 May. De Gaulle answered two days later that he was ready to "assume the powers of the Republic". Many worried as they saw this answer as support for the army. At

a 19 May press conference, de Gaulle asserted again that he was at the

disposal of the country. As a journalist expressed the concerns of some

who feared that he would violate civil liberties, de Gaulle retorted

vehemently: "Have

I ever done that? On the contrary, I have reestablished them when they

had disappeared. Who honestly believes that, at age 67, I would start a

career as a dictator?" A

republican by conviction, de Gaulle maintained throughout the crisis

that he would accept power only from the lawfully constituted

authorities. The crisis deepened as French paratroops from Algeria seized Corsica and a landing near Paris was discussed (Operation Resurrection). Political leaders on many sides agreed to support the General's return to power, except François Mitterrand, Pierre Mendès-France, Alain Savary, the Communist Party, and certain other leftists. On 29 May the French President, René Coty,

appealed to the "most illustrious of Frenchmen" to confer with him and

to examine what was immediately necessary for the creation of a

government of national safety, and what could be done to bring about a

profound reform of the country's institutions. De

Gaulle remained intent on replacing the constitution of the Fourth

Republic, which he blamed for France's political weakness. (Indeed he

had resigned 12 years previously because he believed the parties made

the task of government too difficult.) He set as a condition for his

return that he be given wide emergency powers for six months and that a

new constitution be proposed to the French people. On 1 June 1958, de Gaulle became Premier and was given emergency powers for six months by the National Assembly. On 28 September 1958, a referendum took place and 79.2 percent of those who voted supported the new constitution and the creation of the Fifth Republic. The colonies (Algeria was officially a part of France, not a colony) were given the choice between immediate independence and the new constitution. All African colonies voted for the new constitution and the replacement of the French Union by the French Community, except Guinea,

which thus became the first French African colony to gain independence,

at the cost of the immediate ending of all French assistance. According to de Gaulle, the head of state should represent "the spirit of the nation" to the nation itself and to the world: "une certaine idée de la France" (a certain idea of France). In the November 1958 elections, de Gaulle and his supporters (initially organised in the Union pour la Nouvelle République - Union Démocratique du Travail, then the Union des Démocrates pour la Vème République, and later still the Union des Démocrates pour la République, UDR) won a comfortable majority. In December, de Gaulle was elected President by the electoral college with 78% of the vote, and inaugurated in January 1959. He oversaw tough economic measures to revitalise the country, including the issuing of a new franc (worth 100 old francs). Internationally, he rebuffed both the United Statesand the Soviet Union, pushing for an independent France with its own nuclear weapons,

and strongly encouraged a "Free Europe", believing that a confederation

of all European nations would restore the past glories of the great

European empires. He set about building Franco-German cooperation as the cornerstone of the European Economic Community (EEC), paying the first state visit to Germany by a French head of state since Napoleon. In January 1963, Germany and France signed a treaty of friendship, the Élysée Treaty. France also reduced its dollar reserves, trading them for gold from the U.S. government, thereby reducing the US' economic influence abroad. On 23 November 1959, in a speech in Strasbourg, de Gaulle announced his vision for Europe: ("Yes, it is Europe, from the Atlantic to the Urals, it is the whole of Europe, that will decide the destiny of the world.") Upon

becoming president, de Gaulle was faced with the urgent task of finding

a way to bring to an end the bloody and divisive war in Algeria. French

left-wingers were in favour of granting independence to Algeria and

urged him to seek a way to achieve peace while, at the same time,

avoiding a French loss of face. This stance greatly angered the French settlers and

their metropolitan supporters, and de Gaulle was forced to suppress two

uprisings in Algeria by French settlers and troops, in the second of

which (the Generals' Putsch in April 1961) France herself was threatened with invasion by rebel paratroops. De Gaulle's government also covered up the Paris massacre of 1961, issued under the orders of the police prefect Maurice Papon. He was also targeted by the settlers' resistance group Organisation de l'armée secrète (OAS) and several assassination attempts

were made on him; the most famous is that of 22 August 1962, when he

and his wife narrowly escaped an assassination attempt when their Citroën DS was targeted by machine gun fire arranged by Colonel Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry at the Petit-Clamart. After a referendum on Algerian self-determination carried out in 1961, de Gaulle arranged a cease-fire in Algeria with the March 1962 Evian Accords, legitimated by another referendum a month later. Although the Algerian issue was settled, Prime Minister Michel Debré

resigned over the final settlement and was replaced with Georges

Pompidou on 14 April 1962. France

recognised Algerian independence on 3 July 1962, while an amnesty was

belatedly issued covering all crimes committed during the war,

including the genocide against the Harkis. In just a few months in 1962, 900,000 French settlers left the country. After 5 July, the exodus accelerated in the wake of the French deaths during the Oran massacre of 1962. It had now become clear that the Evian Accords would not be enforced and that the French government had no intention of protecting the settlers. In

September 1962, de Gaulle sought a constitutional amendment to allow

the president to be directly elected by the people and issued another referendum to this end. After a motion of censure voted by the Parliament on 4 October 1962, de Gaulle dissolved the National Assembly and held new elections. Although the left progressed, the Gaullists won an increased majority — this despite opposition from the Christian democratic Popular Republican Movement (MRP) and the National Centre of Independents and Peasants (CNIP) who criticised de Gaulle's euroscepticism and presidentialism. De

Gaulle's proposal to change the election procedure for the French

presidency was approved at the referendum on 28 October 1962 by more

than three-fifths of voters despite a broad "coalition of no" formed by

most of the parties, opposed to a presidential regime. Thereafter the

President was to be elected by direct universal suffrage for the first

time since Louis Napoleon in 1848.

With

the Algerian conflict behind him, de Gaulle was able to achieve his two

main objectives: to reform and develop the French economy, and to

promote an independent foreign policy and a strong stance on the

international stage. This was named by foreign observers the "politics

of grandeur" (politique de grandeur). In the context of a population boom unseen in France since the 18th century, the government under prime minister Georges Pompidou oversaw a rapid transformation and expansion of the French economy. With dirigisme —

a

unique combination of capitalism and state-directed economy — the

government intervened heavily in the economy, using indicative

five-year plans as its main tool. High-profile projects, mostly but not

always financially successful, were launched: the extension of Marseille harbor (soon ranking third in Europe and first in the Mediterranean); the promotion of the Caravelle passenger jetliner (a predecessor of Airbus); the decision to start building the supersonic Franco-British Concorde airliner in Toulouse; the expansion of the French auto industry with state-owned Renault at its center; and the building of the first motorways between Paris and the provinces. With

these projects, the French economy recorded growth rates unrivalled

since the 19th century. In 1964, for the first time in nearly 100 years France's GDP overtook that of the United Kingdom, a position it held until the 1990s. This period is still remembered in France with some nostalgia as the peak of the Trente Glorieuses ("Thirty Glorious Years" of economic growth between 1945 and 1974). He vetoed the British application to join the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1963 because, he said, he thought the United Kingdom lacked the necessary political will to be part of a strong Europe. He further saw Britain as a "Trojan Horse" for the USA. He

maintained there were incompatibilities between continental European

and British economic interests. In addition, he demanded that the

United Kingdom accept all the conditions laid down by the six existing

members of the EEC (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg,

Netherlands) and revoke its commitments to countries within its own

free trade area. He supported a deepening and an acceleration of common

market integration rather than expansion. However,

in this latter respect, a detailed study of the formative years of the

EEC argues that the defence of French economic interests, especially in

agriculture, in fact played a more dominant role in determining de

Gaulle's stance towards British entry than the various political and

foreign policy considerations that have often been cited. The

General's attitude was also influenced by resentments which had come

about during his exile in Britain during the Second World War. Added to

these were fears of an Anglo-American agreement in regard to nuclear

weapons – the USA had provided Britain with Polaris missiles the previous year. In December 1967, claiming continental European solidarity, de Gaulle again rejected British entry into the European Economic Community. The United Kingdom nevertheless became a member of the EEC in January 1973.

As

early as April 1954, de Gaulle had proposed that France should have its

own nuclear weapons. This would enable her to become a partner in any

reprisals and would give her a voice in matters of atomic control. Six years later, on 13 February 1960, France became the world's fourth nuclear power when a nuclear device was exploded in the Sahara some 700 miles south-south-west of Algiers. In November 1967, an article by the French Chief of the General Staff (but inspired by de Gaulle) in the Revue de la Défense Nationale caused international consternation. It was stated that French nuclear force

should be capable of firing ‘in all directions’ – thus including even

America as a target. This surprising statement was intended as a

declaration of French national independence, and was in retaliation to

a warning issued long ago by Dean Rusk that

US missiles would be aimed at France if she attempted to employ atomic

weapons outside an agreed plan. However, criticism of de Gaulle was

growing over his tendency to act alone with little regard for the views of others. In August, concern over de Gaulle's policies had been voiced by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing when he queried ‘the solitary exercise of power’. De

Gaulle was convinced that a strong and independent France could act as

a balancing force between the United States and the Soviet Union, a

policy seen as little more than posturing and opportunism by his

critics, particularly in Britain and the United States, to which France

was formally allied. In January 1964, France established diplomatic

relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC) — the first step towards formal recognition. This was done without first severing links with the Republic of China (Taiwan), led by Chiang Kai-shek. Hitherto the PRC had insisted that all nations abide by a "one China" condition, and at first it was unclear how the matter would be settled. However,

the agreement to exchange ambassadors was subject to a delay of three

months and in February, Chiang Kai-shek resolved the problem by cutting

off diplomatic relations with France. Eight years later U.S. President Richard Nixon visited the PRC and began normalising relations - a policy which was confirmed in the Shanghai Communiqué of 28 February 1972. As part of a European tour, Nixon visited France in 1969. He

and de Gaulle both shared the same non-Wilsonian approach to world

affairs, believing in nations and their relative strengths, rather than

in ideologies, international organisations, or multilateral agreements.

De Gaulle is famously known for calling the United Nations le Machin ("the thing"). In

September and October 1964, despite a recent operation for prostate

cancer and fears for his security, he set out on a punishing

20,000-mile tour of all ten republics in Latin America. He had visited

Mexico the previous year and was again keen to show the French flag and

gain both cultural and economic influence in this new 26-day tour. He

spoke constantly of his resentment of US influence (hegemony) in Latin

America - "that some states should establish a power of political or

economic direction outside their own borders". Yet France could provide

no investment or aid to match that from Washington.

In

December 1965, de Gaulle returned as president for a second seven-year

term, but this time he had to go through a second round of voting in

which he defeated François Mitterrand, who did far better than anyone dreamed possible, gaining 45% of the vote. In February 1966, France withdrew from the common NATO military

command, but remained within the organisation. De Gaulle, haunted by

the memories of 1940, wanted France to remain the master of the

decisions affecting it, unlike in the 1930s, when France had to follow

in step with her British ally. He also declared that all foreign

military forces had to leave French territory and gave them one year to

redeploy. In September 1966, in a famous speech in Phnom Penh (Cambodia), he expressed France's disapproval of the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, calling for a U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam as the only way to ensure peace. As the Vietnam War had its roots in the previous Indochina War,

in which the United States had provided France with aid, this speech

did little to endear de Gaulle to the Americans, even if their leaders

later came to the same conclusion. During the establishment of the European Community, de Gaulle helped precipitate one of the greatest crises in the history of the EC, the Empty Chair Crisis. It involved the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy, but almost more importantly the use of qualified majority voting in

the EC (as opposed to unanimity). In June 1965, after France and the

other five members could not agree, de Gaulle withdrew France's

representatives from the EC. Their absence left the organisation

essentially unable to run its affairs until the Luxembourg compromise was reached in January 1966. De

Gaulle succeeded in influencing the decision-making mechanism written

into the Treaty of Rome by insisting on solidarity founded on mutual

understanding. He vetoed Britain's entry into the EEC a second time, in June 1967. With

tension rising in the Middle East in 1967, de Gaulle on 2 June declared

an arms embargo against Israel, just three days before the outbreak of

the Six-Day War. This, however, did not affect spare parts for the French military hardware with which the Israeli armed forces were equipped. This was an abrupt change in policy. In 1956 France, Britain, and Israel had cooperated in an elaborate effort to retake the Suez Canal from Egypt. Israel's air force operated French Mirage and Mystère jets in the Six-Day War, and its navy was building its new missile boats in Cherbourg.

Though paid for, their transfer to Israel was now blocked by de

Gaulle's government. But they were smuggled out in an operation that

drew further denunciations from the French government. The last boats

took to the sea in December 1969, directly after a major deal between

France and now-independent Algeria exchanging French armaments for

Algerian oil. Under de Gaulle, following the independence of Algeria, France embarked on foreign policy more favourable to the Arab side.

General de Gaulle's position in 1967 at the time of the Six Day War

played a part in France's newfound popularity in the Arab world. Israel turned towards the United States for arms, and toward its own industry. In

a televised news conference on 27 November 1967, de Gaulle described

the Jewish people as "this elite people, sure of themselves and

domineering". In his letter to David Ben-Gurion dated

9 January 1968, he explained that he was convinced that Israel had

ignored his warnings and overstepped the bounds of moderation by taking

possession of Jerusalem, and so much Jordanian, Egyptian, and Syrian

territory by force of arms. He felt Israel had exercised repression and

expulsions during the occupation and that it amounted to annexation. He

said that provided Israel withdrew her forces, it appeared that it

might be possible to reach a solution through the UN framework which

could include assurances of a dignified and fair future for refugees

and minorities in the Middle East, recognition from Israel's neighbors,

and freedom of navigation through the Gulf of Aqaba and the Suez Canal.

The Eastern Region of Nigeria declared itself independent under the name of The Independent Republic of Biafra on

30 May 1967. On July 6 the first shots in the Nigerian civil war were

fired, marking the start of a conflict would last until January 1970. Britain provided military aid to the Federal Republic of Nigeria — yet

more was made available by the Soviet Union. Under de Gaulle's

leadership, France embarked on a period of interference outside the

traditional French zone of influence. A policy geared toward the

break-up of Nigeria put Britain and France into opposing camps.

Relations between France and Nigeria had been under strain since the

third French nuclear explosion in the Sahara in

December 1960. From August 1968, when its embargo was lifted, France

provided limited and covert support to the breakaway province. Although

French arms helped to keep Biafra in action for the final 15 months of

the civil war, its involvement was seen as insufficient and

counterproductive. The Biafran Chief of Staff stated that the French

"did more harm than good by raising false hopes and by providing the

British with an excuse to reinforce Nigeria." In July 1967, de Gaulle visited Canada, which was celebrating its centennial with a world's fair, Expo 67. On 24 July, speaking to a large crowd from a balcony at Montreal's city hall, de Gaulle shouted Vive le Québec! (Long live Quebec!) then added, Vive le Québec libre! (Long live Free Québec!). The Canadian media harshly criticised the statement, and the Prime Minister of Canada, Lester B. Pearson stated that "Canadians do not need to be liberated." De Gaulle left Canada two days later without proceeding to Ottawa as

scheduled. He never returned to Canada. The speech caused outrage in

most of Canada; it led to a serious diplomatic rift between the two

countries. However, the event was seen as a watershed moment by the Quebec sovereignty movement. In the following year, de Gaulle visited Brittany, where he declaimed a poem written by his uncle (also called Charles de Gaulle) in the Breton language. The speech followed a series of crackdowns on Breton nationalism.

De Gaulle was accused of double standards for on the one hand demanding

a "free" Quebec because of its differences from English-speaking

Canada, while on the other oppressing a regionalist movement in

Brittany. De

Gaulle's government was criticised within France, particularly for its

heavy-handed style. While the written press and elections were free,

and private stations were able to broadcast in French from abroad, the state had a monopoly on television and radio (ORTF).

This monopoly meant that the executive was in a position to bias the

news. In many respects, society was traditionalistic and

repressive — this included the position of women. Many

factors contributed to a general weariness of sections of the public,

particularly the student youth, which led to the events of May 1968.

The huge demonstrations and strikes in France in May 1968 severely

challenged de Gaulle's legitimacy. He made a flying visit to Germany and met with Jacques Massu, the then chief of the French forces occupying Germany, to discuss possible army intervention against the protesters. In

a private meeting discussing the students' and workers' demands for

direct participation in business and government he coined the phrase

"La réforme oui, la chienlit non", which can be politely translated as 'reform yes, masquerade/chaos no.' It was a vernacular scatological pun meaning 'chie-en-lit,

no'. The term is now common parlance in French political commentary,

used both critically and ironically referring back to de Gaulle. But

de Gaulle offered to accept some of the reforms the demonstrators

sought. He again considered a referendum to support his moves, but

Pompidou persuaded him to dissolve parliament (in which the government

had all but lost its majority in the March 1967 elections) and hold new

elections instead. The June 1968 elections were a major success for the

Gaullists and their allies; when shown the spectre of revolution or

even civil war, the majority of the country rallied to him. His party

won 358 of 487 seats. Pompidou was suddenly replaced by Maurice Couve de Murville in July. Charles de Gaulle resigned the presidency at noon, 28 April 1969, following the rejection of his proposed reform of the Senate and local governments in a nationwide referendum.

De Gaulle vowed that if the referendum failed, he would resign his

office. Despite an eight-minute-long speech by de Gaulle, the

referendum failed and he duly resigned, whereupon he was replaced by Georges Pompidou. De Gaulle retired once again to Colombey-les-Deux-Églises,

where he died suddenly in 1970, two weeks before his 80th birthday and

in the middle of writing his memoirs. He had generally been in very

robust health until then, despite an operation on his prostate some

years before. He had been sitting in front of the television while

waiting for the start of the news when he felt unwell and collapsed.

His wife called the doctor and the local priest, but by the time they

arrived he had died: the cause of death was a heart attack. De

Gaulle had made arrangements that insisted that his funeral would be

held at Colombey, and that no presidents or ministers attend his

funeral - only his Compagnons de la Libération. Heads of state had to content themselves with a simultaneous service at Notre-Dame Cathedral. He

was carried to his grave on an armoured reconnaissance vehicle, and as

he was lowered into the ground the bells of all the churches in France

tolled starting from Notre Dame and spreading out from there. He was

buried on November 12. He

specified that his tombstone bear the simple inscription of his name

and his dates of birth and death. Therefore, it simply says: "Charles

de Gaulle, 1890–1970". De Gaulle was nearly destitute when

he died. When he retired, he did not accept the pensions to which he

was entitled as a retired president and as a retired general. Instead,

he only accepted a pension to which colonels are entitled. His family

had to sell the Boisserie residence. It was purchased by a foundation

and is currently the Charles de Gaulle Museum. Charles

de Gaulle married Yvonne Vendroux on 7 April 1921. They had three

children: Philippe (born 1921), Élisabeth (1924), who married general Alain de Boissieu, and Anne (1928–1948). Anne had Down's syndrome and died at the age of 20. One of Charles de Gaulle's grandsons, also named Charles De Gaulle, was a member of the European Parliament from 1994 to 2004, his last tenure being for the National Front. Another grandson, Jean de Gaulle, was a member of the French Parliament until his retirement in 2007.

His expression, "Europe, from the Atlantic to the Urals", has often been cited throughout the history of European integration. It became, for the next ten years, a favourite political rallying cry of de Gaulle's. His vision stood in contrast to the Atlanticism of the United States and Britain, preferring instead a Europe that would act as a third pole between

the United States and the Soviet Union. By including in his ideal of

Europe all the territory up to the Urals, de Gaulle was implicitly

offering détente to the Soviets, while his phrase was also interpreted as excluding the United Kingdom from a future Europe.“ Oui, c’est l’Europe, depuis l’Atlantique jusqu’à l’Oural, c’est toute l’Europe, qui décidera du destin du monde. ”