<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Ernst Schröder, 1841

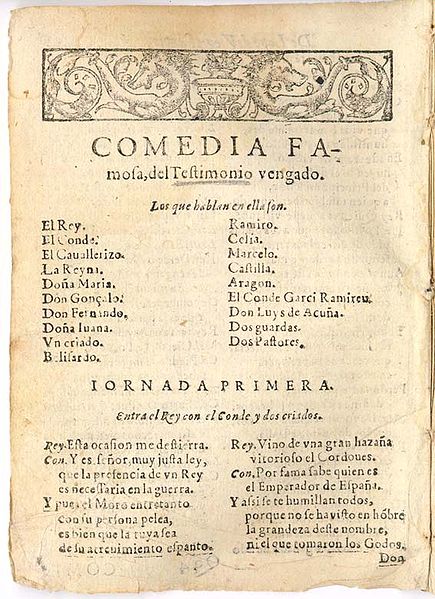

- Playwright Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio, 1562

- President of Czechoslovakia Ludvík Svoboda, 1895

PAGE SPONSOR

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (25 November 1562 – 27 August 1635) was one of the most important playwrights and poets of the Spanish Golden Century Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish letters is second only to that of Cervantes, while the sheer volume of his literary output is unequalled, making him one of the most prolific authors in the history of literature.

Nicknamed "The Phoenix of Wits" and "Monster of Nature" (because of the sheer volume of his work) by Miguel de Cervantes,

Lope de Vega renewed the Spanish theatre at a time when it was starting

to become a mass cultural phenomenon. He defined the key

characteristics of it, and along with Calderón de la Barca and Tirso de Molina,

he took Spanish baroque theatre to its greater limits. Because of the

insight, depth and ease of his plays, he is regarded among the best

dramatists of Western literature, his plays still being represented worldwide. He was also one of the best lyric poets

in the Spanish language, and author of various novels. Although not

well known in the English-speaking world, his plays were presented in

England as late as the 1660s, when diarist Samuel Pepys recorded having

attended some adaptations and translations of them, although he omits

mentioning the author. He is attributed some 3,000 sonnets, 3 novels, 4 novellas, 9 epic poems, and about 1,800 plays. Although the quality of all of them is not the same, at least 80 of his plays are considered masterpieces. A friend to Quevedo and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, the sheer volume of his lifework made him envied by not only contemporary authors such as Cervantes and Góngora, but also by many others: for instance, Goethe once wished he had been able to produce such a vast and colourful work. Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio was born in Madrid to a family of undistinguished origins, recent arrivals in the capital from Valle de Carriedo in Cantabria, whose breadwinner, Félix de Vega, was an embroiderer. The

first indications of young Lope's genius became apparent in his

earliest years. At the age of five he was already reading Spanish and

Latin, by his tenth birthday he was translating Latin verse, and he

wrote his first play when he was 12. His fourteenth year found him enrolled in the Colegio Imperial, a Jesuit school in Madrid, from which he absconded to take part in a military expedition in Portugal. Following that escapade, he had the good fortune of being taken into the protection of the Bishop of Ávila, who recognized the lad's talent and saw him enrolled in the University of Alcalá.

Following graduation Lope was planning to follow in his patron's

footsteps and join the priesthood, but those plans were dashed by his

falling in love and realizing that celibacy was not for him. In 1583 Lope enlisted in the army, and he saw action with the Spanish Navy in the Azores.

Following this he returned to Madrid and began his career as a

playwright in earnest. He also began a love affair with Elena Osorio,

an actress and the daughter of a leading theater owner. When, after

some five years of this torrid affair, Elena spurned Lope in favor of

another suitor, his vitriolic attacks on her and his family landed him

in jail for libel and, ultimately, earned him the punishment of eight years' banishment from Castile. He

went into exile undaunted, in the company of the 16-year-old Isabel de

Urbina, the daughter of a prominent advisor at the court of Philip II,

whom he was subsequently forced to marry. A few weeks after their

marriage, however, Lope signed up for another tour of duty with the

Spanish navy: this was the summer of 1588, and the Invincible Armada was about to sail against England. Lope's luck again served him well, and his ship, the San Juan,

was one of the few vessels to make it home to Spanish harbors in the

aftermath of that failed expedition. Back in Spain, he settled in the

city of Valencia to live out the remainder of exile and to recommence, as prolifically as ever, his career as a dramatist. In 1590 he was appointed to serve as the secretary to the Duke of Alba, which required him to relocate to Toledo. In

1595, following Isabel's death, he left the Duke's service and – eight

years having passed – returned to Madrid. There were other love affairs

and other scandals: Antonia Trillo de Armenta, who earned him another

lawsuit, and Micaela de Luján, who inspired a rich series of sonnets and

rewarded him with four children. In 1598 he married Juana de Guardo,

the daughter of a wealthy butcher. Nevertheless, his trysts with others

– including Micaela – continued. The

1600s were the years when Lope's literary output reached its peak. He

was also employed as a secretary, but not without various additional

duties, by the Duke of Sessa. Once that decade was over, however, his

personal situation took a turn for the worse. His favorite son, Carlos

Félix (by Juana), died and, in 1612, Juana herself died in

childbirth. Micaela also disappears from the history around this point.

Deeply affected, Lope gathered his surviving children from both unions

together under one roof. His writing in the early 1610s also assumed

heavier religious influences and, in 1614, he joined the priesthood. The

taking of holy orders did not, however, impede his romantic dalliances,

although it is somewhat unclear what role his employer the duke,

fearful of losing his secretary, played in this by supplying him with

various female companions. The most notable and lasting of his

relationships during this time was with Marta de Nevares, who would

remain with him until her death in 1632. Further

tragedies followed in 1635 with the loss of Lope, his son by Micaela

and a worthy poet in his own right, in a shipwreck off the coast of Venezuela,

and the abduction and subsequent abandonment of his beloved youngest

daughter Antonia. Lope de Vega took to his bed and died of Scarlet fever, in Madrid, on 27 August of that year. A rapid survey of Lope's nondramatic works can begin with those published in Spain under the title Obras Sueltas (Madrid, 21 vols., 1776–79). The more important elements of this collection include La Arcadia (1598), a pastoral romance, one of the poet's most wearisome productions; La Dragontea (1598), a fantastic history in verse of Sir Francis Drake's last expedition and death; El Isidro (1599), a narrative of the life of Saint Isidore, patron saint of Madrid, composed in octosyllabic quintillas; La Hermosura de Angélica (1602), in three books, a sort of continuation of Ariosto's Orlando Furioso. Lope de Vega is one of the greatest Spanish poets of his time, along with Luis de Góngora and Francisco de Quevedo.

In the 1580s and 1590s his poems of moorish and pastoral themes were

extremely popular, in part because Lope — who appears in these poems as

a moor called Zaide or a shepherd called Belardo — portrayed elements of

his own love affairs. In 1602 he published two hundred sonnets with his La Hermosura de Angélica and in 1604 he republished them with new material in his Rimas. In 1614 his religious sonnets appeared in a book entitled Rimas sacras, which was another huge bestseller. Finally, in 1634 a third book of similar name, Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos,

which has been considered his masterpiece as a poet and the most modern

poem book of the 17th century: Lope created a heteronym, Tomé de

Burguillos, a poor scholar who is in love with a maid called Juana and

who observes society from a cynical and disillusional position. It

curious to note that he always treated the art of comedy-writing as one

of the humblest of trades and protested against the supposition that in

writing for the stage his aim was glory and not money. Spanish drama,

if not literally the creation of Lope, at least owes him its definitive

form – the three act comedia –

regardless of the precepts of the prevailing school of his

contemporaries. Lope accordingly felt bound to prove that from the

point of view of literary art, he attached no value to the rustic

traits of his humble age: in his Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609) – his artistic manifesto and the justification of his style, breaking the neoclassical three unities (place,

time, and action) – Lope begins by showing that he knows as well as

anyone the established rules of poetry, and then excuses himself for

his inability to follow them on the ground that the "vulgar" Spaniard

cares nothing about them: "Let us then speak to him in the language of

fools, since it is he who pays us." Lope belonged in literature to what may be called the school of good sense: he boasted that he was a Spaniard pur sang,

steadfastly maintained that a writer's business is to write so as to

make himself understood, and took the position of a defender of the

language of ordinary life. Unfortunately, the books he read, his

literary connections, and his fear of Italian criticism all exercised

an influence upon his naturally robust spirit and, like so many others,

he caught the prevalent contagion of mannerism and of pompous phraseology. His

literary culture was chiefly Latin-Italian and, while he defends the

tradition of the nation and the pure simplicity of the old Castilian,

he still did not wish to be taken for an uninformed person, a writer

devoid of classical training: he especially emphasizes the fact that he

has passed through university, and he continually accentuates the

difference between those who know Latin and ignorant laymen. Another

reason for him to speak deprecatingly of his dramatic works was the

fact that the vast majority of them were written in haste and to order.

Lope does not hesitate to confess that "more than a hundred of my

comedies have taken only twenty-four hours to pass from the Muses to

the boards of the theatre." His biographer Pérez de

Montalbán, a great admirer of this kind of cleverness, tells how

on certain occasion in Toledo, Lope composed fifteen acts in as many

days: that is to say, five entire comedies in two weeks. In

spite of some discrepancies in the figures, Lope's own records indicate

that by 1604 he had composed, in round numbers, as many as 230

three-act plays (comedias). The figure had risen to 483 by 1609, to 800 by 1618, to 1000 by 1620, and to 1500 by 1632. Montalbán, in his Fama Póstuma (1636) set down the total of Lope's dramatic productions at 1800 comedias and

more than 400 shorter sacramental plays. Of these 637 plays are known

to us by their titles, but only the texts of some 450 are extant. Many

of these pieces were printed during Lope's lifetime, either in

compilations of works by various authors or as separate issues by

booksellers who surreptitiously bought manuscripts from the actors or

had the unpublished comedy written down from memory by persons they

sent to attend the first performance. Therefore such pieces that do not

figure in the collections published under Lope's own direction – or

under that of his friends – cannot be regarded as perfectly authentic,

and it would be unfair to hold their author responsible for all the

faults and defects they exhibit. The

classification of this enormous mass of dramatic literature is a task

of great difficulty. The terms traditionally employed – comedy,

tragedy, and the like – do not apply to Lope's oeuvre. Another approach

to categorization is needed. In the first place, Lope's work

essentially belongs to the drama of intrigue: be the subject what it

may, it is always the plot that determines everything else. It is from

history, Spanish history in particular, that Lope borrows more than

from any other source. It would in fact be difficult to say what

national and patriotic subjects, from the reign of the half-fabulous King Pelayo down

to the history of his own age, he did not put upon the stage.

Nevertheless, Lope's most celebrated plays belong to the class called capa y espada or "cloak and dagger", where the plots are almost always love intrigues complicated with affairs of honor, most commonly involving the petty nobility of medieval Spain. Among the best known works of this class are El perro del hortelano (The Dog in the Manger), La viuda de Valencia (The Widow from Valencia), and El maestro de danzar.

In some of these Lope strives to set forth some moral maxim and to

illustrate its abuse by a living example. Thus, on the theme that

poverty is no crime, we have the play entitled Las Flores de Don Juan.

Here, he uses the history of two brothers to illustrate the triumph of

virtuous poverty over opulent vice, while simultaneously (but

indirectly) attacking the institution of primogeniture,

which often places in the hands of an unworthy person the honor and

substance of a family when the younger members would be much better

qualified for the trust. Such morality pieces are, however, rare in

Lope's repertory; generally, his sole aim is to amuse and stir his

public, not troubling himself about its instruction. His focus remains

fixed on the plot.