<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Anatoly Ivanovich Mal'cev, 1909

- Guitarist James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix, 1942

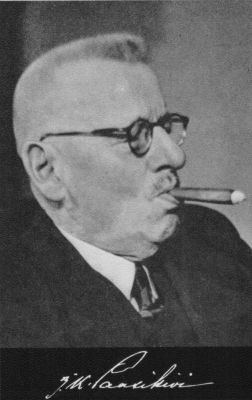

- 7th President of Finland Juho Kusti Paasikivi, 1870

PAGE SPONSOR

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (November 27, 1870 – December 14, 1956) was the seventh President of Finland (1946 – 1956). He also served as Prime Minister of Finland (1918 and 1944 – 1946), and was generally an influential figure in Finnish economics and politics for over fifty years. He is particularly remembered as a main architect of Finland's foreign policy after the Second World War.

He was born as Johan Gustaf Hellsten in 1870 at Hämeenkoski in Päijänne Tavastia in Southern Finland, the son of August Hellsten, a merchant, and Karolina Wilhelmina Selin. He Finnicized his name to Juho Kusti Paasikivi in 1885. Paasikivi

was orphaned at the age of 14 and was raised by his aunt. The young

Paasikivi was an enthusiastic athlete and gymnast. He received most of

his elementary education in Hämeenlinna, where he exhibited an early appetite for reading, and was the best pupil in his class. He entered the University of Helsinki in 1890, graduating with a Bachelor's degree in 1892, and as a lawyer in

1897. That year he married his first wife, Anna Matilda Forsman

(1869 - 1931). They had four children, Annikki (1898 – 1950), Wellamo

(1900 – 1966), Juhani (1901 - 1942), and Varma (1903 - 1941). In 1901,

Paasikivi became a Doctor of Law, and was associate professor of Administrative Law at Helsinki University 1902-1903. He left this post to become Director-in-Chief of Treasury of the Grand Duchy of Finland, a position he retained until 1914. For practically all of his adult life, Paasikivi moved in the inner circles of Finland's politics. He supported greater autonomy and an independent Cabinet (Senate) for Finland, and resisted Russia's panslavic intentions

to make Russian the only official language everywhere in the Russian

Empire. He belonged, however, to the more complying Fennoman or Old Finn Party,

opposing radical and potentially counter-productive steps which could

be perceived as aggressive by the Russians. Paasikivi served as a Finnish Party member

of Parliament 1907 - 1909 and 1910 - 1913. He served as a member of the

Senate 1908 - 1909, as Head of the Finance Division. During the First World War Paasikivi

began to have doubts about the Fennoman Party's obedient line. In 1914,

after resigning his position at the Treasury, and also standing down as

a member of Parliament, Paasikivi left public life and office. He

became Chief General Manager of the Kansallis-Osake-Pankki (KOP) bank, retaining that position until 1934. Paasikivi also served as a member of Helsinki City Council 1915 - 1918. After the February Revolution in

Russia 1917, Paasikivi was appointed to committee that began to

formulate new legislation for a modernized Grand Duchy. Initially he

supported increased autonomy within the Russian Empire, in opposition to the Social Democrats in the coalition-Senate, who in vain strived for more far-reaching autonomy; but after the Bolshevik October Revolution Paasikivi championed full independence — albeit in the form of constitutional monarchy. During the Civil War in Finland Paasikivi was firmly on the side of the White government. As Prime Minister May - November 1918 he strived for continued constitutional monarchy with Frederick Charles of Hesse (a

German Prince) as king, intending to ensure Finland of German support

against Bolshevist Russia. However, as Germany lost the World War,

monarchy had to be scrapped for a Republic more in the taste of the

victorious Entente. Paasikivi's Senate resigned, and he returned to the KOP bank. Paasikivi, as politically conservative, was a firm opponent of Social Democrats in the cabinet, or Communists in the Parliament. Tentatively he supported the semi-fascist Lapua movement which

requested radical measures against the political Left. But eventually the Lapua movement radicalized further, assaulting also Ståhlberg,

the Liberal former President of Finland, and Paasikivi like many other

supporters turned away from the radical Right. In 1934 he became

chairman for the Conservative Kokoomus party, as a champion of democracy, and achieved the party's rehabilitation after its suspicious closeness to the Lapua movement and the failed coup d'état, the Mäntsälä Rebellion. Widowed

in 1931, he re-married Allina (Alli) Valve (1879 – 1960) in 1934 and

resigned from politics. However, he was persuaded to accept the

position as Ambassador to Sweden, at this time regarded as Finland's

most important embassy. Authoritarian regimes seizing power in Germany, Poland and Estonia made Finland increasingly isolated while the Soviet Union threatened. After the gradual dissolution of the League of Nations, and as it turned out that France and the United Kingdom were uninterested, Sweden was

the only regime left who possibly could give Finland any support at

all. Approximately since the failed Lapua coup, Paasikivi and Mannerheim had belonged to a close circle of Conservative Finns discussing how this could be achieved. In Stockholm Paasikivi

strived for Swedish defence guarantees, alternatively a defensive

alliance or a defensive union between Finland and Sweden. Since the

Civil War the relations between Swedes and Finns had been frosty. The

revolutionary turmoil at the end of the World War had in Sweden led to Parliamentarism,

increased democracy, and a dominant role for the Swedish Social

Democrats. In Finland, however, the result had been a disastrous Civil War and a total defeat for Socialism. At the same time as when Paasikivi arrived in Stockholm, it became known that President Svinhufvud retained

his aversion for Parliamentarism and (after pressure from Paasikivi's

Conservative Party) had declined to appoint a Cabinet with Social

Democrats as Ministers. This didn't improve Paasikivi's reputation

among the Swedish Social Democrats dominating the government, who were

sufficiently suspicious due to his association with Finland's

Monarchist orientation in 1918, and the failed Lapua coup in 1932. Things actually improved, partly due to Paasikivi's efforts, partly since President Kallio had been elected. As President, Kallio approved of Parliamentarism and appointed Social Democrats to the Cabinet. But the suspicions between Finland and Sweden were too strong: During the Winter War Sweden's

support for Finland was considerable, but short of one critical

feature: Sweden neither declared war on the Soviet Union nor sent

regular troops to Finland's defense. This made many Finns, including

Paasikivi himself, judge his mission in Stockholm to have been a

failure.

Prior to the Winter War, Paasikivi became the Finnish representative in the negotiations in Moscow. Seeing that Stalin did

not intend to change his policies, he supported compliance with some of

the demands. When the war broke out, Paasikivi was asked to enter Risto Ryti’s

Cabinet as a Minister without portfolio — in practice in the role of a

distinguished political advisor. He ended up in the Cabinet's leading

triumvirate together with Risto Ryti and Foreign Minister Väinö Tanner (chairman of the Social Democrats). He also led the negotiations for an armistice and the peace, and continued his mission in Moscow as an ambassador. In Moscow he was, by necessity, isolated from the most secret thoughts

in Helsinki, and when he found out that these thoughts ran in the

direction of revanche with Germany's aid, he resigned. Paasikivi

retired for the second time. In the summer of 1941, when the Continuation War had

begun, he took up writing his memoirs. By 1943 he concluded that

Germany was going to lose the war and that Finland was in great danger

as well. However, his initial opposition against the pro-German

politics of 1940-41 was too well known, and his first initiatives for

peace negotiations were met with little support both from Field Marshal

Mannerheim and from Risto Ryti, who now had become President. Immediately after the war, Mannerheim appointed Paasikivi Prime Minister. For the first time in Finland a Communist, Yrjö Leino,

was included in the Cabinet. Paasikivi's policies were realist, but

radically different than those of the previous 25 years. His main

effort was to prove that Finland would present no threat to the Soviet

Union, and that both countries would gain from confident peaceful

relations. He had to comply with many Soviet demands, including the War

Crimes trial. When Mannerheim resigned, Parliament selected Paasikivi

to succeed him as President of the Republic. Paasikivi was then aged

seventy-five. Paasikivi

had thus come a long way from his earlier classical conservatism. He

now was willing to co-operate regularly with the Social Democrats and,

when necessary, even with the Communists, as long as they acted

democratically. He only once accepted his party, the Conservatives,

into the government as President - and even that government lasted only

about six months and was considered more a caretaker or civil-servant

government than a regular parliamentary government. He even appointed a

Communist or a People's Democrat, Mauno Pekkala, as Prime Minister in

1946. Paasikivi's political flexibility had its limits, however, and

this was shown in the Communists' alleged coup attempt or coup plans in

the spring of 1948. He ordered some units of the army and navy to

Helsinki to defend the capital against a possible Communist attack.

Most modern Finnish historians deny that most Communists wanted a

violent coup, especially not without the Soviet support. Later in the

spring, when the Parliament passed a non-confidence motion against the

Communist Interior Minister Leino, due to controversy about the

treatment of prisoners whom he had ordered to be deported to the Soviet

Union (they were mostly Ingrians and East Karelians), Paasikivi had to

dismiss Leino who refused to resign at once. After the 1948

parliamentary elections, where the Communists dropped from the largest

to the third largest party, Paasikivi refused to let them into the

government - and the Communists remained in the opposition until 1966. As President, Paasikivi kept Finland's foreign relations in the foreground, trying to ensure a stable peace and wider freedom of action. Paasikivi concluded that, all the fine rhetoric aside,

Finland had to adapt to superpower politics and sign treaties with the

Soviet Union to avoid a worse fate. Thus he managed to stabilize

Finland's position. This "Paasikivi doctrine" was adhered to for

decades, and was named Finlandization in the 1970s. It

should be noted that he was helped in his relations with the Soviet

leaders by his ability to speak some Russian, so he did not have to use

interpreters all the time, like his successor Kekkonen did. Having

studied in Russia as a young man, Paasikivi also knew the classic

Russian literature and culture. Paasikivi

stood for re-election in the Presidential election of 1950, where he

won 171 out of the 300 electoral college votes. The priorities of his

second term were centred largely on domestic politics, in contrast to

his first term. Stalin's

death made Paasikivi's job easier. As a lover of sports, and a former

athlete and gymnast, Paasikivi had the pleasure, during his second term

of office, of opening the 1952 Summer Olympics held in Helsinki. By

the end of Paasikivi's second six-year term, Finland had gotten rid of

the most urgent political problems resulting from the lost war. The Karelian refugees had been resettled, the war reparations had been paid, rationing had ended and in January 1956 the Soviet Union removed its troops from Porkkala marine base at Helsinki. He

did not actively seek re-election when his second term ended in 1956,

ending his term on March 1, 1956, at the age of eighty-five. More

specifically, Paasikivi was willing to serve as President for about two

more years if a great majority of politicians asked him to do so. He

appeared as a dark-horse presidential candidate on the second ballot of

the electoral college on February 15, 1956, but was eliminated as the

least popular candidate. His last-minute candidacy was based on a

misunderstood message from some Conservatives which made him believe

that enough Agrarians and Social Democrats would support him. After his

unsuccessful last-minute presidential candidacy, Paasikivi felt

betrayed by those politicians who asked him to participate in the

election. He even denied giving his consent to the presidential

candidacy in a public statement. He died in December, not yet having finished his

memoirs.