<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Friedrich Engels, 1820

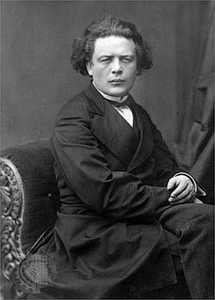

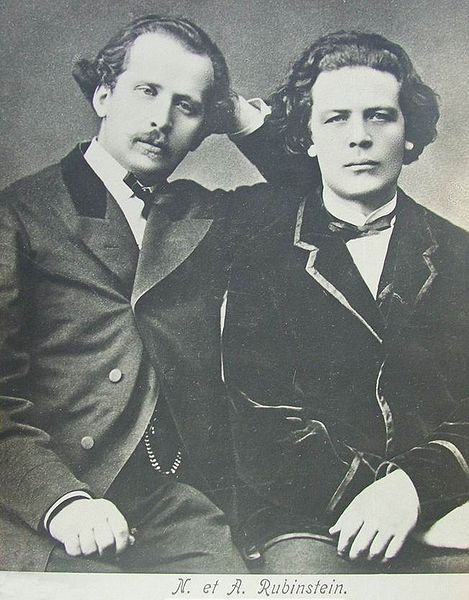

- Composer Anton Grigorevich Rubinstein, 1829

- Prime Minister of France Achille Léonce Victor Charles, 3rd duc de Broglie, 1785

PAGE SPONSOR

Anton Grigorevich Rubinstein (Russian: Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн) (November 28, 1829 – November 20, 1894) was a Russian-Jewish pianist, composer and conductor. As a pianist he was regarded as a rival of Franz Liszt, and he ranks amongst the great keyboard virtuosos. He also founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which, together with Moscow Conservatory founded by his brother Nikolai Rubinstein, helped establish a reputation for musical skill among the subjects of the Tsar of Russia.

Rubinstein was born to Jewish parents in the village of Vikhvatinets in the district of Podolsk, Russia, (now known as Ofatinţi in Transnistria, Republic of Moldova), on the Dniestr River, about 150 kilometers northwest of Odessa. Before he was 5 years old, his paternal grandfather ordered all members of the Rubinstein family to convert from Judaism to Russian Orthodoxy. Rubinstein, brought up as a Christian at least in name, lived in a household where three languages were spoken — Yiddish, Russian and German. Much later, when his musical "Russianness" was called into question by musical nationalist Mily Balakirev and others in The Five, Rubinstein might have been thinking of this part of his childhood, among other things, when he wrote in his notebooks,

Russians call me German, Germans call me Russian, Jews call me a Christian, Christians a Jew. Pianists call me a composer, composers call me a pianist. The classicists think me a futurist, and the futurists call me a reactionary. My conclusion is that I am neither fish nor fowl – a pitiful individual.

Conversion allowed the Rubinsteins to travel freely, something not permitted for Jews in Russia at the time. Rubinstein's father opened a pencil factory in Moscow. His mother, a competent musician, began giving him piano lessons at five. He apparently progressed rapidly. Within a year and a half, Alexander Villoing, a leading Moscow piano teacher, heard and accepted Rubinstein as a non-paying student. Rubinstein made his first public appearance, a charity benefit concert, in Moscow's Petrovsky Park at the age of nine. Later that year Rubinstein's mother sent him, accompanied by Villoing, to enroll at the Paris Conservatoire. Director Luigi Cherubini, however, refused an audition to Rubinstein, due to the many young prodigies who had flooded the Paris musical scene.

Rubinstein and Villoing remained in Paris a year. In December 1840, Rubinstein played in the Salle Erard for an audience that included Frederic Chopin and Franz Liszt.

Chopin invited Rubinstein to his studio and played for him. Liszt

acclaimed the young Rubinstein as his successor but advised Villoing to

take him to Germany to study composition. Instead of following Liszt's

advice, Villoing took Rubinstein on an extended concert tour of Europe

and Western Russia. They finally returned to Moscow in June 1843, after

an absence of three and a half years. Shortly before the pair returned,

Liszt had played in Saint Petersburg and reiterated to Rubinstein's

mother the advice which he had given Villoing. Determined to follow

Liszt's advice, she wanted a thorough grounding in musical theory for

both Rubinstein and his younger brother Nikolai.

To raise money for this, she sent Rubinstein and Villoing on a tour of

Russia. When the tour ended, Rubinstein and Nikolai were dispatched to Saint Petersburg to play for Tsar Nicholas I and the Imperial family at the Winter Palace. Rubinstein was 14 years old; Nikolai was eight. In spring 1844, Rubinstein, Nikolai, his mother and his sister Luba travelled to Berlin. Here he met with, and was supported by, Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer.

Mendelssohn, who had heard Rubinstein when he had toured with Villoin,

said he needed no further piano study but sent Nikolai to Theodor Kullak for instruction. Meyerbeer directed both boys to Siegfried Dehn for

work in composition and theory. Also, a Greek Orthodox priest

instructed the two boys in the catechism and Russian grammar, and both

boys studied other subjects. These non-musical lessons were

short-lived. Still, Rubinstein grew up to be a highly cultured,

widely-read artist. He was fluent in Russian, German, French and

English and could read Italian and Spanish literature. Word

came in the summer of 1846 that Rubinstein's father was gravely ill.

Rubinstein was left in Berlin while his mother, sister and brother

returned to Russia. At first he continued his studies with Dehn, then

with Adolf Bernhard Marx,

while composing in earnest. Now 17, he knew he could no longer pass as

a child prodigy. He sought out Liszt in Vienna, hoping Liszt would

accept him as a pupil. Liszt's

reaction to Rubinstein in Vienna was highly atypical of his famously

generous nature. After Rubinstein had played his audition, Liszt is

reported to have coldly said, "A talented man must win the goal of his

ambition by his own unassisted efforts." At this point, Rubinstein was

living in acute poverty. Liszt did nothing to help him. Other calls Rubinstein made to potential patrons came to no avail. Rubinstein

began giving piano lessons, continued composing, even wrote literary,

philosophical and critical essays. After a year in Vienna he gave a

concert in the Bösendörfersaal. It did not go well; months of

composition had severely reduced his time practicing the piano.

Together with a flautist he embarked on a concert tour of Hungary, then

returned to Berlin and continued giving lessons. The Revolution of 1848 forced

Rubinstein back to Russia. Spending the next five years mainly in Saint

Petersburg, Rubinstein taught, gave concerts and performed frequently

at the Imperial court. The Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, sister to Tsar Nicholas I,

became his most devoted patroness. By 1852, he had become a leading

figure in Saint Petersburg's musical life, performing as a soloist and

collaborating with some of the outstanding instrumentalists and

vocalists who came to the Russian capital. He also composed assiduously. After a number of delays, including some difficulties with the censor, Rubinstein's first opera, Dmitry Donskoy (now

lost except for the overture), was performed at the Bolshoy Theater in

St. Petersburg in 1852. Three one-act operas written for Elena Pavlovna

followed. He also played and conducted several of his works, including

the Ocean

Symphony

in its original four-movement form, his Second Piano Concerto and

several solo works. It was partly his lack of success on the Russian

opera stage that led Rubinstein to consider going abroad once more to

secure his reputation as a serious artist. In 1854 Rubinstein began a four-year concert tour of Europe.

This was his first major concert tour in a decade. Now 24, he felt

ready to offer himself to the public as a fully developed pianist as

well as a composer of worth. He very shortly reestablished his

reputation as a virtuoso. Ignaz Moscheles wrote in 1855 what would become a widespread opinion about Rubinstein: "In power and execution he is inferior to no one." As

was the penchant at the time, much of what Rubinstein played were his

own compositions. At several concerts, Rubinstein alternated between

conducting his orchestral works and playing as soloist in one of his

piano concertos. One high point for him was leading the Leipzig

Gewandhaus orchestra in his Ocean Symphony

on November 16, 1854; as this was considered one of the most

prestigious places to have a musical work performed, having the Ocean heard there was considered a high honor. Although

reviews were mixed about Rubinstein's merits as a composer, they were

more favorable about him as a performer when he played a solo recital a

few weeks later. Rubinstein spent one tour break, in the winter of 1856-7, with Elena Pavlovna and much of the Imperial royal family at Nice.

These three months would become crucial ones. Rubinstein had already

noted both his patroness's great intelligence and her great influence in terms of reform over her brother Nicholas I. (She would exercise a similar influence over her nephew, Alexander II, resulting in, among other things, the freeing of the serfs.)

Now patroness and artist, with others present, began discussing plans

to raise the level of musical education in their homeland. These

discussions bore fruit at first in the founding of the Russian Musical Society (RMS) in 1859. The opening of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, the first music school in Russia and an outgrowth of the RMS, followed in 1862. Rubinstein not only founded it and was its first director but also recruited an imposing pool of talent for its faculty. Some

in Russian society were surprised that a Russian music school would

actually attempt to be Russian. One "fashionable lady," when told by

Rubinstein that classes would be taught in Russian and not a foreign

language, exclaimed, "What, music in Russian! That is an original

idea!" Rubinstein adds, And

surely it was surprising that the theory of Music was to be taught for

the first time in the Russian language at our Conservatory....

Hitherto, if any one wished to study it, he was obliged to take lessons

from a foreigner, or to go to Germany. There

were also those who feared the school would not be Russian enough.

Rubinstein drew a tremendous amount of criticism from the Russian

nationalist music group known as The Five. Mikhail Zetlin, in his book on The Five, writes, The

very idea of a conservatory implied, it is true, a spirit of academism

which could easily turn it into a stronghold of routine, but then the

same could be said of conservatories all over the world. Actually the

Conservatory did raise

the level of musical culture in Russia. The unconventional way chosen

by Balakirev and his friends was not necessarily the right one for

everybody else. It was during this period that Rubinstein drew his greatest success as a composer, beginning with his Fourth Piano Concerto in 1864 and culminating with his opera The Demon in 1871. Between these two works are the orchestral works Don Quixote, which Tchaikovsky found "interesting and well done," though "episodic," and the opera Ivan IV Grozniy, which was premiered by Balakirev. Borodin commented on Ivan IV that

"the music is good, you just cannot recognize that it is Rubinstein.

There is nothing that is Mendelssohnian, nothing as he used to write

formerly." At the behest of the Steinway & Sons piano

company, Rubinstein toured the United States during the 1872-3 season.

Steinway's contract with Rubinstein called on him to give 200 concerts

at the then unheard-of rate of 200 dollars per

concert (payable in gold — Rubinstein distrusted both United States banks

and United States paper Money), plus all expenses paid. Rubinstein

stayed in America 239 days, giving 215 concerts — sometimes two and three

a day in as many cities. Rubinstein wrote of his American experience, May

Heaven preserve us from such slavery! Under these conditions there is

no chance for art — one simply grows into an automaton, performing

mechanical work; no dignity remains to the artist; he is lost.... The

receipts and the success were invariably gratifying, but it was all so

tedious that I began to despise myself and my art. So profound was my

dissatisfact that when several years later I was asked to repeat my

American tour, I refused pointblank.... Despite

his misery, Rubinstein made enough money from his American tour to give

him financial security for the rest of his life. Upon his return to

Russia, he "hastened to invest in real estate", purchasing a dacha in Peterhof, not far from Saint Petersburg, for himself and his family. Rubinstein

continued to make tours as a pianist and give appearances as a

conductor. In 1887, he returned to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

with the goal of improving overall standards. He removed inferior

students, fired and demoted many professors, made entrance and

examination requirements more stringent and revised the curriculum. He

led semi-weekly teachers' classes through the whole keyboard literature

and gave some of the more gifted piano students personal coaching.

During the 1889-90 academic year he gave weekly lecture-recitals for

the students. He resigned again — and left Russia — in 1891 over

Imperial

demands that Conservatory admittance, and later annual prizes to

students, be awarded along racial quotas instead of purely by merit.

These quotas were effectively to disadvantage Jews. Rubinstein

resettled in Dresden and

started giving concerts again in Germany and Austria. Nearly all of

these concerts were charity benefit events. Rubinstein also coached a

few pianists and taught his only private piano student, Josef Hofmann. Hofmann would become one of the finest keyboard artists of the 20th century. Despite

his sentiments on ethnic politics in Russia, Rubinstein returned there

occasionally to visit friends and family. He gave his final concert in

Saint Petersburg on January 14, 1894. With his health failing rapidly,

Rubinstein moved back to Peterhof in the summer of 1894. He died there

on November 20 of that year, having suffered from heart disease for some time. The former Troitskaya street in Saint Petersburg where he lived is now named after him.

By

1867, ongoing tensions with the Balakirev camp, along with related

matters, led to intense dissension within the Conservatory's faculty.

Rubinstein resigned and returned to touring throughout Europe. Unlike

his previous tours, he began increasingly featuring the works of other

composers. In previous tours, Rubinstein had played primarily his own

works.