<Back to Index>

- Physician Sir Patrick Manson, 1844

- Painter Henry Lerolle, 1848

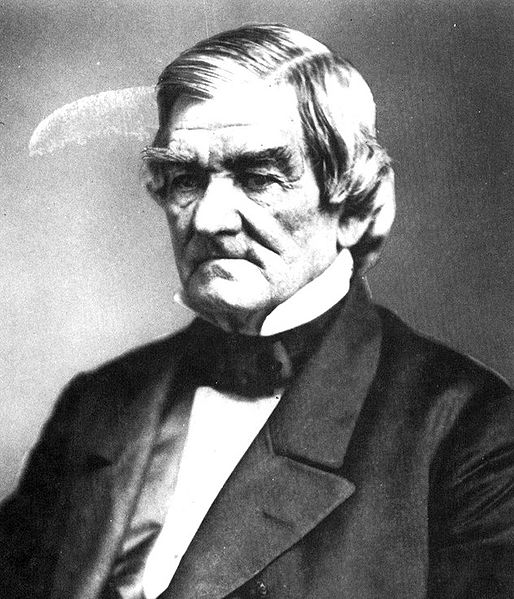

- Cherokee Chief John Ross, 1790

John Ross (October 3, 1790 - August 1, 1866), also known as Guwisguwi (a mythological or rare migratory bird), was Principal Chief of the Cherokee Native American Nation from 1828-1866. Described as the Moses of his people, Ross led the Nation through tumultuous years of development, relocation to Oklahoma, and the American Civil War.

Between 1790 and 1845, the Cherokee attempted to become a nation state, lost their ancestral land, endured removal to the Indian Territory,

and suffered the destructive Civil War, in which their early alliance

with the Confederacy jeopardized their nation. Throughout these

tumultuous years, the dominant political figure in the Cherokee Nation

was John Ross, whose leadership spanned the entire period. By ancestry,

Ross was seven-eighths Scottish,

and he grew up in both Cherokee and frontier American environments. He

had been educated in English by white men and was a poor speaker of the

Cherokee language, but his bi-cultural background allowed him to

represent the Cherokee to the Americans in government. He was one of

the wealthiest men of the Nation. In terms of heritage, education,

status, and economic pursuits, Ross closely resembled his political

foes President Andrew Jackson and Governor George R. Gilmer of

Georgia. He was among the elite of the Cherokee Nation. By his own

person he called into question many of the 19th century

European-American assumptions about race and Native American. Ross'

life had a pattern similar to those of prominent Anglo-Métis in

North America and Canada. Scots and English fur traders in North

America were typically men of social status and financial standing who

married high-ranking women of Native American ancestry. These alliances

helped both the traders and Native Americans. They educated their

children in bicultural and multilingual environments. The mixed-race

children often married and rose to positions of stature in society,

both in political and economic terms. In

the changing environment which Cherokees encountered in the 19th

century, they needed the skills and language which Ross had developed.

The majority of Cherokees ardently supported Ross, electing him as

their principal chief in every election from 1828 through 1860. Given

his stature and the controversy over Native American affairs in the

struggle over territory, there were also a vocal minority of Cherokees

and a generation of political leaders in Washington who considered Ross

to be dictatorial, greedy, and an "aristocratic leader [who] sought to

defraud" the Cherokee Nation. Ross also had influential supporters in Washington, including Thomas L. McKenney, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1824

- 1830). He described Ross as the father of the Cherokee Nation, a

Moses who "led... his people in their exodus from the land of their

nativity to a new country, and from the savage state to that of

civilization." Ross was born in Turkeytown, Alabama, along the Coosa River, near Lookout Mountain,

to Mollie McDonald, of mixed-race Cherokee and Scots ancestry, and

Daniel Ross, a Scots immigrant trader. Ross' Scots heritage in North

America began with William Shorey, a Scottish interpreter who married Ghigooie,

a "full-blood" member of the Cherokee Bird clan. In 1769, their

daughter Anna Shorey married John McDonald, a Scottish fur trader at Fort Loudoun in

Tennessee. The Scottish and English fur traders were men of social

standing who arrived with some financial backing. Their children,

whether mixed-race or not, in these years shared their status and class. Their daughter Mollie McDonald in 1786 married Daniel Ross, a Scotsman who began to live among the Cherokee as a trader during the American Revolution. Ross

spent his childhood with his parents in the area of Lookout Mountain.

He saw much of Cherokee society as he encountered the fullblood

Cherokee who frequented his father's trading company. As a child, Ross

was allowed to participate in Cherokee events such as the Green Corn Festival.

Despite Daniel's willingness to allow his son to participate in some

Cherokee customs, the elder Ross was determined that John also receive

a rigorous classical education. After being educated at home, Ross

pursued higher studies with the Reverend Gideon Blackburn,

who established two schools in southeast Tennessee for Cherokee

children. Classes were in English and students were mostly bicultural

like John Ross. Ross finished his education at an academy in South West

Point, Tennessee. At

the age of twenty, having completed his education and with bilingual

skills, Ross was appointed as US Indian agent to the western Cherokee and sent to Arkansas. He served as an adjutant in a Cherokee regiment during the War of 1812. With them he participated in fighting at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the British-allied Creek tribe. Ross

then began a series of business ventures. He derived the majority of

his wealth from cultivating 170 acres (0.69 km2) in Tennessee worked by twenty slaves. In 1816 he founded Ross's Landing and

ferry. In addition, Ross established a trading firm and warehouse. In

total, he earned upwards on one-thousand dollars a year. After Ross and

the Cherokee were removed to Oklahoma, settlers changed the name of

Ross's Landing to Chattanooga. In 1827, Ross moved to Rome, Georgia, to be closer to New Echota,

the Cherokee capital, and leading politicians of the nation. In Rome,

Ross established a ferry along the headwaters of the Coosa River close

to the home of Major Ridge, another wealthy and influential Cherokee

leader. He also held 20 slaves who cultivated 170 acres

(0.69 km2). By December 1836,

Ross's property was appraised at $23,665. He was then one of the five

wealthiest men in the Cherokee Nation. The

years 1812 to 1827 were also a period of political apprenticeship for

Ross. He had to learn how to conduct negotiations with the United

States and the skills required to run a national government. After

1814, Ross's political career, as a Cherokee legislator and diplomat,

progressed with the support of individuals such as Principal Chief Pathkiller, Associate Chief Charles R. Hicks, and Major Ridge,

an elder statesman of the Cherokee Nation. In 1813, as relations with

the United States became more complex, older, uneducated Chiefs like

Pathkiller could not effectively defend Cherokee interests. The

ascendancy of Ross represented an acknowledgment by the Cherokee that

an educated, English-speaking leadership was of national importance.

Both Pathkiller and Hicks saw Ross as the future leader of the Cherokee

Nation and trained him for this work. Ross served as clerk to

Pathkiller and Hicks, where he worked on all financial and political

matters of the nation. Equally

important in the education of the future leader of the Cherokees was

instruction in the traditions of the Cherokee Nation. In a series of

letters to Ross, Hicks outlined what was known of Cherokee traditions. In

1816, the National Council named Ross to his first delegation to

Washington. The delegation of 1816 was directed to resolve the

sensitive issues of national boundaries, land ownership, and white

intrusions on Cherokee land. Of the delegates, only Ross was fluent in

English, making him the central figure in the negotiations. This was a

unique position for a young man in Cherokee society, which

traditionally favored older leaders. Ross's

first political position came in November 1817 with the formation of

the National Council. He was elected to the thirteen-member body, where

each man served two-year terms. The National Council was created to

consolidate Cherokee political authority after General Jackson made

two treaties with small cliques of Cherokees representing minority

factions. Membership in the National Council placed Ross among the

ruling elite of the Cherokee leadership. In November 1818, on the eve of the General Council meeting with Cherokee agent Joseph McMinn,

Ross was elevated to the presidency of the National Committee. He held

this position through 1827. The Council selected Ross because they

perceived him to have the diplomatic skill necessary to rebuff US

requests to cede Cherokee lands. In this task, Ross did not disappoint

the Council. McMinn offered $200,000 US for removal of the Cherokees

beyond the Mississippi, which Ross refused. In

1819, the Council sent Ross to Washington again. He was assuming a

larger role among the leadership. The purpose of the delegation was to

clarify the provisions of the Treaty of 1817. The delegation had to

negotiate the limits of the ceded land and hope to clarify the

Cherokee's right to the remaining land. John C. Calhoun, the Secretary of War,

pressed Ross to cede large tracts of land in Tennessee and Georgia.

Such pressure from the US government would continue and intensify. In

October 1822, Calhoun requested that the Cherokee relinquish their land

claimed by Georgia, in fulfillment of the United States' obligation

under the Compact of 1802. Before responding to Calhoun's proposition,

Ross first ascertained the sentiment of the Cherokee people. They were

unanimously opposed to cession of land. In

January 1824, Ross traveled to Washington to defend the Cherokees'

possession of their land. Calhoun offered two solutions to the Cherokee

delegation: either relinquish title to their lands and remove west, or

accept denationalization and become citizens of the United States.

Rather than accept Calhoun's ultimatum, Ross made a bold departure from

previous negotiations. He pressed the Nation's complaints. On April 15,

1824, Ross took the dramatic step of directly petitioning Congress.

This fundamentally altered the traditional relationship between an

Indian nation and the US government. Never

before had an Indian nation petitioned Congress with grievances. In

Ross' correspondence, what had previously had the tone of petitions of

submissive Indians were replaced by assertive defenders. He was able to

argue as well as whites, subtle points about legal responsibilities. This change was apparent to individuals in Washington, including future president John Quincy Adams.

He wrote, "[T]here was less Indian oratory, and more of the common

style of white discourse, than in the same chief's speech on their

first introduction." Adams

specifically noted Ross' work as "the writer of the delegation" and

remarked that "they [had] sustained a written controversy against the

Georgia delegation with greate advantage." The Georgia delegation acknowledged Ross' skill in an editorial in The Georgia Journal,

which charged that the Cherokee delegation's letters were fraudulent

because they were too refined to have been written or dictated by an

Indian. In January 1827, Pathkiller, the Cherokee's principal chief, and Charles R. Hicks,

Ross's mentor, both died. In a letter dated February 23, 1827, to

Colonel Hugh Montgomery, the Cherokee Agent, Ross wrote that with the

death of Hicks, he had assumed responsibility for all public business

of the nation. The year 1827 marked not only the elevation of Ross to

principal chief pro tem,

but also the climax of political reform of the Cherokee government. The

Cherokee Council passed a series of laws creating a bicameral national

government. In 1822 they created the Cherokee Supreme Court, capping

the creation of a three-branch government. In May 1827, Ross was

elected to the twenty-four member constitutional committee, which

drafted a constitution calling for a principal chief, a council of the

principal chief, and a National Committee, which together would form

the General Council of the Cherokee Nation. Although the constitution

was ratified in October 1827, it did not take effect until October

1828, at which point Ross was elected principal chief. He was

repeatedly reelected and held this position until his death in 1866. The

Cherokee had created a system of government with delegated authority

capable of dependably formulating a clear, long-range policy to protect

national rights. They had a strong leader in Ross who understood the

complexities of the United States government and could use that

knowledge to implement national policy. On

December 20, 1828, Georgia, fearful that the United States would be

unable to effect the removal of the Cherokee Nation, enacted a series

of oppressive laws which stripped the Cherokee of their rights and were

calculated to force the Cherokee to remove. In this climate, Ross led

another delegation to Washington in January 1829 to resolve disputes

over non-payment of annuities and the boundary between Georgia and the

Cherokee Nation. Rather than lead the delegation into futile

negotiations with President Jackson, Ross wrote an immediate memorial

to Congress, forgoing the customary correspondence and petitions to the

President. Ross found support in Congress from individuals in the National Republican Party, such as Senators Henry Clay, Theodore Frelinghuysen, and Daniel Webster and Representatives Ambrose Spencer and David (Davy) Crockett. Despite this support, in April 1829, John H. Eaton,

Secretary of War (1829 - 1831), informed Ross that President Jackson

would support the right of Georgia to extend her laws over the Cherokee

Nation. In May 1830, Congress endorsed Jackson's policy of removal by

passing the Indian Removal Act. It authorized the president to set aside lands west of the Mississippi to exchange for the lands of the Indian nations in the east. When

Ross and the Cherokee delegation failed in their efforts to protect

Cherokee lands through dealings with the executive branch and Congress,

Ross took the radical step of defending Cherokee rights through the

U.S. courts. In June 1830, at the urging of Senator Webster and Senator

Frelinghuysen, the Cherokee delegation selected William Wirt, US Attorney General in the Monroe and Adams administrations, to defend Cherokee rights before the U.S. Supreme Court. Wirt argued two cases on behalf of the Cherokee: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia. In his decision, Chief Justice John Marshall never

acknowledged that the Cherokee were a sovereign nation. He did not

compel President Jackson to take action that would defend the Cherokee

from Georgia's laws. The Cherokee Nation claim was denied on the

grounds that the Cherokees were a "domestic dependent sovereignty" and

as such did not have the right as a nation state to sue Georgia. The

court later expanded on this position in Worcester v. Georgia,

ruling that Georgia could not extend its laws into Cherokee lands. It

was not because they were fully sovereign, however, but because they

were a domestic dependent sovereignty. As such the court ruled the

Cherokee were dependent not on the state of Georgia, but on the United

States. According to the series of rulings, Georgia could not extend

its laws because that was a power in essence reserved to the federal

government. The Cherokee were considered sovereign enough to legally

resist the government of Georgia, and were encouraged to do so. The

court carefully maintained that the Cherokee were ultimately dependent

on the federal government and were not a true nation state, nor fully

sovereign. Thus the dispute was made moot when federal legislation in

the form of the Indian Removal Act exercised the federal government's

legal power to handle the whole affair. The series of decisions

embarrassed Jackson politically, as Whigs attempted to use the issue in

the 1832 election. They largely supported his earlier opinion that the

"Indian Question" was one that was best handled by the federal

government, and not local authorities. In an unusual meeting in May

1832, Supreme Court Justice John McLean spoke

with the Cherokee delegation to offer his views on their situation.

McLean's advice was to "remove and become a Territory with a patent in

fee simple to the nation for all its lands, and a delegate in Congress,

but reserving to itself the entire right of legislation and selection

of all officers." McLean's advice precipitated a split within the Cherokee leadership as John Ridge and Elias Boudinot began

to doubt Ross' leadership. In February 1833, Ridge wrote Ross

advocating that the delegation dispatched to Washington that month

should begin removal negotiations with Jackson. However, Ridge and Ross

did not have irreconcilable worldviews; neither believed that the

Cherokee could fend off Georgian usurpation of Cherokee land. Although

Ridge and Ross agreed on this point, they clashed about how best to

serve the Cherokee Nation. In

this environment, Ross led a delegation to Washington in March 1834 to

try to negotiate alternatives to removal. Ross made several proposals;

however, the Cherokee Nation may not have approved any of Ross' plans,

nor was there reasonable expectation that Jackson would settle for any

agreement short of removal. These offers, coupled with the lengthy

cross-continental trip, indicated that Ross' strategy was to prolong

negotiations on removal indefinitely. He hoped to wear down Jackson's

opposition to a treaty that did not require Cherokee removal. Ross'

strategy was flawed because it was susceptible to the United States'

making a treaty with a minority faction. On May 29, 1834, Ross received

word from John H. Eaton, that a new delegation, including Major Ridge,

John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Ross' younger brother Andrew,

collectively called the Ridge Party, had arrived in Washington with the

goal of signing a treaty of removal. The two sides attempted

reconciliation, but by October 1834 still had not come to an agreement.

In January 1835 the factions were again in Washington. Pressured by the

presence of the Ridge Party, Ross agreed on February 25, 1835, to

exchange all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi for land west of

the Mississippi and 20 million dollars. He made it contingent on the

General Council's accepting the terms. Lewis Cass,

Secretary of War, believing that this was yet another ploy to delay

action on removal for an additional year, threatened to sign the treaty

with John Ridge. On December 29, 1835, the Ridge Party signed the removal treaty with

the U.S., although this action was against the will of the majority of

Cherokees. Ross unsuccessfully lobbied against enforcement of the

treaty. Those Cherokees who did not emigrate to the Indian Territory by 1838 were forced to do so by General Winfield Scott. This forced removal came to be known as the "Trail of Tears".

Accepting defeat, Ross convinced General Scott to allow him to

supervise much of the removal process. On the Trail of Tears, Ross lost

his wife Quatie, a full-blooded Cherokee woman of whom little is known. She died shortly before reaching Little Rock on the Arkansas River. Ross later married again, to Mary Brian Stapler. In

the Indian Territory, Ross helped draft a constitution for the entire

Cherokee nation in 1839, and was chosen as chief of the nation. The American Civil War was

a test for Ross to hold the nation together, preserve national rights

acquired by treaties, and ensure national welfare. As the southern

states seceded and formed the Confederacy, slave-owning Cherokee, who formed the core of the old Treaty Party, banded together under the leadership of Stand Watie and pushed for a treaty with the new Confederate government. The

Cherokees' own severe internal dissension from the 1820 to the 1840s

over issues of acculturation and removal motivated Ross' overriding

concern for unity in 1861. Furthermore, Ross understood that "the

relations which the Cherokee people sustain toward their white brethren

have been established by subsisting treaties with the United States..." The

Cherokee right to land, self-government, and annuities from the sale of

ancestral lands were all secured in treaties with the United States;

Ross knew they would be lost if the Cherokee Nation joined the

Confederacy. Seeing the conflict between treaties with the Union and

some members' sympathies with the Confederacy, Ross opted for a policy

of neutrality to unify the nation and ensure that Cherokee rights were

not lost. In February 1861, Ross began a vigorous campaign among the leaders of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek Nations

to advance his policy, emphasizing loyalty to the United States to

protect their treaty rights. The policy of neutrality was a skillful

attempt to spare the Cherokee the depredations of war and the potential

loss of their precious rights, but by July 1861, Ross had been informed

that "difficulties of a serious character existed...between half and

full blood Cherokees..." Ross

attempted to salvage the situation by convening the Executive Council

on August 21, 1861, "for the purpose of devising means by which the

people may become deeply impressed with the importance of being united

in sentiment & action for the welfare of our Common Country." Ross

explained how the Cherokee' treaty relationship with the United States

dictated the policy of neutrality. Nonetheless, he concluded with, "in

my opinion, the time has now arrived when you should signify your

consent for the authorization of the nation to adopt preliminary steps

for an alliance with the Confederate States..." His

shift was understandable in terms of traditional Cherokee political

ethos. Any Cherokee leader would have been expected to calmly state and

restate the same opinion until a consensus emerged, at which point all

Cherokee would either accept the emerging sentiment or withdraw. Ross

perceived the forces pushing for ties with the Confederacy to be in the

majority; in traditional Cherokee style, he acceded to the majority

sentiment in order to preserve unity and harmony. Despite

his attempt to keep the Cherokee united, not all agreed with this

position. Before the end of 1861, the Civil War had come to the Indian

Territory; the failure of Ross to shield the five nations was complete.

The Cherokees had chosen the wrong ally to defend the nation's rights,

for the South could not protect the Cherokee Nation. The Union Army invaded it in July 1862. With

this defeat, the Cherokee nation was abandoned by the Confederacy.

Fearing the loss of the rights for which they had sacrificed their

ancestral lands, Ross led a large part of the population back to

allegiance to the Union cause. A regiment of Cherokee men enlisted in

the Union Army. Ross went to Washington, where the Cherokee leadership

hoped he could "advocate our cause, to represent us [in Washington] and

exert all your influence to preserve our nationality and our rights." In a letter to President Lincoln before

his arrival, Ross outlined a six-point defense of Cherokee rights based

on mutual observance of treaty obligations. The skillfully crafted

argument absolved Cherokee disloyalty by claiming the treaties were

abrogated by the failure of the United States to fulfill the promises

it had contracted. Lincoln, a trained lawyer, expressed doubt about the

logic of Ross' arguments. Although unwilling to accede to the idea that

the United States had special obligations to the Cherokee, Lincoln

acknowledged the Cherokees' general right to protection by the

government. Ross

stayed in Washington from October 1862 through July 1865. In 1863 Stand

Watie's troops burned his home of Park Hill in Oklahoma, demonstrating

the strong conflicts within the Cherokee nation. Ross continued to

defend Cherokee treaty rights and tried to ensure the welfare of the

nation for the duration of the war. The government-in-exile received

grievances and updates from citizens who remained in the Nation. Ross,

who gained access to members of Congress and the Executive, lobbied to

aid the Cherokee and other western Indian nations. Although Ross was

able to establish and maintain correspondences with Lincoln, Edwin M. Stanton,

Secretary of War; and William P. Dole, Commissioner of Indian Affairs,

his task remained arduous. His pleas received sympathetic hearing, but

he had not convinced the government of its obligations to the

Cherokees. Ultimately, Ross was successful in getting Cherokee

regiments armed for defense, which allowed the Cherokee to return to

the Union. He was never successful in settling the Cherokees' rights

with the United States. In

his final annual message on October 1865, Ross assessed the Cherokee

experience during the Civil War and his performance as chief. The

Cherokee could "have the proud satisfaction of knowing that we honestly

strove to preserve the peace within our borders, but when this could

not be done,...borne a gallant part in the defense...of the cause which

has been crowned with such signal success." Ross died on August 1, 1866 in Washington, DC. The City of Chattanooga named the Market Street Bridge in Ross's honor. The

city of Rossville Georgia, just south of the Tennessee state line is

named in Ross' honor. The "John Ross House" is located there, and is

one of the oldest surviving homes in the Chattanooga area. Ross lived

there as a child and received much of his formal education until moving

closer to New Echota. Ross sold the home to relatives in 1828.