<Back to Index>

- Anatomist Albrecht von Haller, 1708

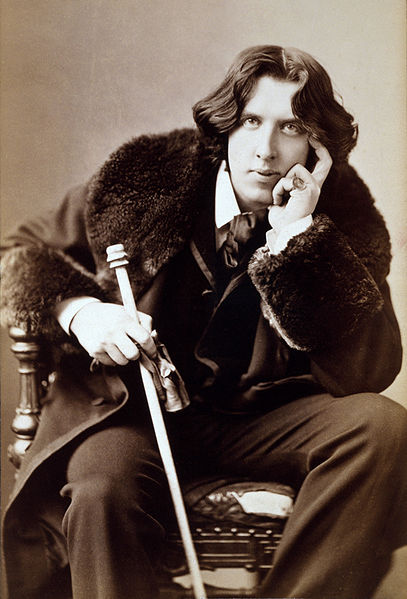

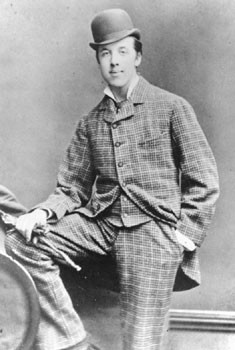

- Writer Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde, 1854

- 1st Prime Minister of Israel David Ben-Gurion, 1886

PAGE SPONSOR

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 1854 – 30 November 1900) was an Irish writer, poet, and prominent aesthete.

His parents were successful Dublin intellectuals, and from an early age

he was tutored at home, where he showed his intelligence, becoming

fluent in French and German. He attended boarding school for six years,

then matriculated to university at seventeen years old. Reading Greats, Wilde proved himself to be an outstanding classicist, first at Dublin, then at Oxford.

After university, Wilde moved around trying his hand at various

literary activities: he published a book of poems and toured America

lecturing extensively on aestheticism. He then returned to London,

where he worked prolifically as a journalist for four years. Known for

his biting wit, flamboyant dress, and glittering conversation, Wilde

was one of the most well-known personalities of his day. He next

produced a series of dialogues and essays that developed his ideas

about the supremacy of art. However, it was his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray –

still widely read – that brought him more lasting recognition. He

became one of the most successful playwrights of the late Victorian era

in London with a series of social satires which continue to be

performed, especially his masterpiece The Importance of Being Earnest. At

the height of his fame and success, Wilde suffered a dramatic downfall

in a sensational series of trials. He sued his lover's father for

libel, though the case was dropped at trial. After two subsequent

trials, Wilde was imprisoned for two years' hard labour, having been convicted of "gross indecency" with other men. In prison he wrote De Profundis,

a dark counterpoint to his earlier philosophy of pleasure. Upon his

release he left immediately for France, never to return to Ireland or

Britain. There he wrote his last work, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a long, terse poem commemorating the harsh rhythms of prison life. He died destitute in Paris at the age of forty-six. Oscar Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin (now home of the Oscar Wilde Centre, Trinity College, Dublin) the second of three children born to Sir William Wilde and Jane Francesca Wilde, two years behind William ("Willie"). Jane Wilde, under the pseudonym "Speranza" (the Italian word for 'Hope'), wrote poetry for the revolutionary Young Irelanders in 1848 and was a life-long Irish nationalist. She read the Young Irelanders' poetry to Oscar and Willie, inculcating a love of these poets in her sons. Lady Wilde's interest in the neo-classical revival showed in the paintings and busts of ancient Greece and Rome in her home. William Wilde was Ireland's leading oto-ophthalmologic (ear and eye) surgeon and was knighted in 1864 for his services to medicine. He also wrote books about Irish archaeology and peasant folklore. A renowned philanthropist, his dispensary for the care of the city's poor at the rear of Trinity College, Dublin, was the forerunner of the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital, now located at Adelaide Road. In

addition to his children with his wife, Sir William Wilde was the

father of three children born out of wedlock before his marriage: Henry

Wilson, born in 1838, and Emily and Mary Wilde, born in 1847 and 1849,

respectively, of different parentage to Henry. Sir William acknowledged

paternity of his illegitimate children and provided for their

education, but they were reared by his relatives rather than with his

wife and legitimate children. In

1855, the family moved to No. 1 Merrion Square, where Wilde's sister,

Isola, was born the following year. The Wildes' new home was larger

and, with both his parents' sociality and success soon became a "unique

medical and cultural milieu"; guests at their salon included Sheridan le Fanu, Charles Lever, George Petrie, Isaac Butt, William Rowan Hamilton and Samuel Ferguson. Until

he was nine, Oscar Wilde was educated at home, where a French bonne and

a German governess taught him their languages. He then attended Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, Fermanagh. Until his early twenties, Wilde summered at the villa his father built in Moytura, County Mayo. There the young Wilde and his brother Willie played with George Moore. Isola died aged eight of meningitis. Wilde's poem Requiescat is dedicated to her memory: "Tread lightly, she is near Wilde left Portora with a royal scholarship to read classics at Trinity College, Dublin, from 1871 to 1874, sharing rooms with his older brother Willie Wilde. Trinity, one of the leading classical schools, set him with scholars such as R.Y. Tyrell, Arthur Palmer, and his tutor, J.P. Mahaffy who inspired his interest in Greek literature.

Wilde, despite later reservations, called Mahaffy "my first and best

teacher" and "the scholar who interested me in Greek things". For his part Mahaffy boasted of having created Wilde; later, he would name him "the only blot on my tutorship". As a student Wilde worked with Mahaffy on the latter's book Social Life in Greece. Wilde

established himself as an outstanding student: he came first in his

class in his first year, won a scholarship by competitive examination

in his second, and then, in his finals, won the Berkeley Gold Medal,

the highest academic award at Trinity. The University Philosophical Society also

provided an education, discussing intellectual and artistic subjects

such as Rosetti and Swinburne weekly. Wilde quickly became an

established member – the members' suggestion book for 1874 contains two

pages of banter (sportingly) mocking Wilde's emergent aestheticism. He

presented a paper entitled "Aesthetic Morality". He was encouraged to compete for a demyship to Magdalen College, Oxford – which he won easily, having already studied Greek for over nine years. At Magdalen he read Greats from 1874 to 1878, from where he applied to join the Oxford Union, but failed to be elected. Attracted by its dress, secrecy and ritual, Wilde petitioned the Apollo Masonic Lodge at Oxford, and was soon raised to the sublime degree of Master Mason. During

a resurgent interest in Freemasonry in his third year, he commented he

"would be awfully sorry to give it up if I secede from the Protestant

Heresy". He

was deeply considering converting to Catholicism, discussing the

possibility with clergy several times. In 1877, Wilde was left

speechless after an audience with Pope Pius IX in Rome. He eagerly read Cardinal Newman's books, and became more serious in 1878, when he met the Reverend Sebastian Bowden, a priest in the Brompton Oratory who

had received some high profile converts. Neither his father, who

threatened to cut off his funds, nor Mahaffy thought much of the plan;

but mostly Wilde, the supreme individualist, baulked at the last minute

from pledging himself to any formal creed. On the appointed day of his

baptism, Fr Bowden received a bunch of altar lilies instead. Wilde

retained a lifelong interest in Catholic theology and liturgy. While at Magdalen College, Wilde became particularly well known for his role in the aesthetic and decadent movements. He wore his hair long, openly scorned "manly" sports though he occasionally boxed, and decorated his rooms with peacock feathers, lilies, sunflowers, blue china and other objets d'art, once remarking to friends whom he entertained lavishly, "I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china." The

line quickly became famous, accepted as a slogan by aesthetes but used

against them by critics who sensed in it a terrible vacuousness. Some elements disdained the aesthetes, but their languishing attitudes and showy costumes became a recognised pose. Wilde was once physically attacked by a group of four fellow students, and dealt with them single-handedly, surprising critics. By

his third year Wilde had truly begun to create himself and his myth,

and saw his learning developing in much larger ways than merely the

prescribed texts. This attitude resulted in him being rusticated for one term, when he nonchalantly returned to college late from a trip to Greece with Prof. Mahaffy. Wilde was deeply impressed by John Ruskin and Walter Pater,

who argued for the central importance of art in life. He did not meet

Prof. Pater until his third year, but had been enthralled by his Studies in the History of the Renaissance, published during Wilde's final year in Trinity. Pater

argued that man's sensibility to beauty should be refined above all

else, and that each moment should be felt to its fullest extent. Years

later in De Profundis, Wilde called Pater's Studies... "that book that has had such a strange influence over my life". He

learned tracts of the book by heart, and carried it with him on travels

in later years. Pater gave Wilde his sense of almost flippant devotion

to art, though it was Ruskin who gave him a purpose for it. Ruskin

despaired at the self-validating aestheticism of Pater; for him the

importance of art lay in its potential for the betterment of society.

He too admired beauty, but it must be allied with and applied to moral

good. When Wilde eagerly attended his lecture series The Aesthetic and Mathematic Schools of Art in Florence,

he learned about aesthetics as simply the non-mathematical elements of

painting. Despite being given to neither early rising nor manual

labour, Wilde volunteered for Ruskin's project to convert a swampy

country lane into a smart road neatly edged with flowers. Wilde won the 1878 Newdigate Prize for his poem Ravenna, which reflected on his visit there the year before, and he duly read it at Encaenia. In November 1878, he graduated with a rare double first in his B.A. of Classical Moderations and Literae Humaniores (Greats). Wilde wrote a friend, "The dons are 'astonied' beyond words – the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!" After graduation from Oxford, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he met again Florence Balcombe, a childhood sweetheart. She, however, became engaged to Bram Stoker (who later wrote Dracula), and they married in 1878. Wilde

was disappointed but stoic: he wrote to her, remembering "the two sweet

years – the sweetest years of all my youth" they had spent together. He

also stated his intention to "return to England, probably for good".

This he did in 1878, only briefly visiting Ireland twice. Unsure of his next step, he wrote to various acquaintances enquiring about Classics positions at Oxbridge. The Rise of Historical Criticism was

his submission for the Chancellor's Essay prize of 1879, which, though

no longer a student, he was still eligible to enter. Its subject,

"Historical Criticism among the Ancients" seemed ready-made for Wilde –

with both his skill in composition and ancient learning – but he

struggled to find his voice with the long, flat, scholarly style. Unusually, no prize was awarded that year. With the last of his inheritance from the sale of his father's houses, he set himself up as a bachelor in London. At 27 years old Wilde had been publishing lyrics and poems in magazines, especially in Kottabos and the Dublin University Magazine, since his entering Trinity College. In mid-1881, Poems collected, revised and expanded his poetic efforts. The

book was generally well received, and sold out its first print run of

750 copies, prompting further printings in 1882. Bound in a rich,

enamel, parchment cover (embossed with gilt blossom) and printed on

hand-made Dutch paper, Wilde would present many copies to the

dignitaries and writers who received him over the next few years. The Oxford Union condemned the book for alleged plagiarism in

a tight vote. The librarian, who had requested the book for the

library, returned the presentation copy to Wilde with a note of apology. The 1881 British Census listed Wilde as a boarder at 1 Tite Street, Chelsea, where Frank Miles, a society painter, was the head of the household. Wilde would spend the next six years in London and Paris, and in the United States where he travelled to deliver lectures.

The aesthetic movement was caricatured in Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera Patience (1881). While Patience was a success in New York City, its producers were unsure how well aestheticism was known in the rest of America. So Richard D'Oyly Carte invited Wilde for a lecture tour of North America, simultaneously priming the pump for the U.S. tour of Patience and selling one of the most charming aesthetes to the public. Wilde arrived on 3 January 1882 aboard the SS Arizona reputedly

telling a customs officer that "I have nothing to declare except my

genius", although the first recording of this remark was many years

afterward, and Wilde's best lines were usually quoted immediately in

the press. Wilde criss-crossed the country on a gruelling schedule, lecturing in a new town every few days. During his tour of the United States and Canada, Wilde was mercilessly caricatured in the press. For example, The Wasp, a San Francisco newspaper, published a cartoon ridiculing Wilde and aestheticism but he was also well received in such settings as the mining town of Leadville, Colorado. The Springfield Republican commented on Wilde's behaviour during his visit to Boston to

lecture on aestheticism, suggesting that Wilde's conduct was more of a

bid for notoriety rather than a devotion to beauty and the aesthetic.

Wilde's teaching was criticised by T.W. Higginson,

a cleric and abolitionist, who wrote in "Unmanly Manhood" of his

general concern that Wilde, "whose only distinction is that he has

written a thin volume of very mediocre verse", would improperly

influence the behaviour of men and women. Though

Wilde's press reception was hostile, he was the toast of the town,

feted in the most fashionable salons in every city he visited.

His earnings, plus expected income from The Duchess of Padua, allowed him to move to Paris between February and mid-May 1883; there he met Robert Sherard,

whom he entertained constantly. "We are dining on the Duchess tonight",

Wilde would declare before taking him to a fancy restaurant. In August he briefly returned to New York for the production of Vera, his first play, after it was turned down in London. He reportedly entertained the other passengers with Ave Imperatrix!, A Poem On England, about the rise and fall of empires. E.C. Stedman, in Victorian Poets describes this "lyric to England" as "manly verse – a poetic and eloquent invocation". Wilde's presence was again notable, the play was initially well received by the

audience, but when the critics returned lukewarm reviews attendance

fell sharply and the play closed a week after it had opened. He was left to return to England and lecturing: Personal Impressions of America, The Value of Art in Modern Life, and Dress were among his topics. In London, he had been introduced to Constance Lloyd in 1881, daughter of Horace Lloyd, a wealthy Queen's Counsel. She happened to be visiting Dublin in 1884, when Wilde was lecturing at the Gaiety Theatre (an 18 year old W.B. Yeats was

also among the audience). He proposed to her, and they married on 29

May 1884 at the Anglican St. James Church in Sussex Gardens, Paddington, London. Constance's

annual allowance of £250 was generous for a young woman (it would

be equivalent to about £19,300 in current value), but the Wildes'

tastes were relatively luxurious and, after preaching to others for so

long, their home was expected to set new standards of design. No. 16,

Tite Street was duly renovated in seven months at considerable expense.

The couple had two sons, Cyril (1885) and Vyvyan (1886). Wilde was the sole literary signatory of George Bernard Shaw's petition for a pardon of the anarchists arrested (and later executed) after the Haymarket massacre in Chicago in 1886. Robert Ross had

read Wilde's poems before they met, and he was unrestrained by the

Victorian prohibition against homosexuality, even to the extent of

estranging himself from his family. A precocious seventeen year old, by Richard Ellmann's account, he was "...so young and yet so knowing, was determined to seduce Wilde". Wilde,

who had long alluded to Greek love, and – though an adoring father –

was put off by the carnality of his wife's second pregnancy, succumbed

to Ross in Oxford in 1886. Criticism over artistic matters in the Pall Mall Gazette provoked

a letter in self-defence, and soon Wilde was a contributor to that and

other journals during the years 1885–1887. He enjoyed reviewing and

journalism, it was a form that suited his style: he could organise and

share his views on art, literature and life, yet it was less tedious

than lecturing. Buoyed up, his reviews were largely chatty and positive. Wilde, like his parents before him, also supported the cause of Irish Nationalism. When Charles Stewart Parnell was falsely accused of inciting murder Wilde wrote a series of astute columns defending him in the Daily Chronicle. His

flair, having previously only been put into socialising, suited

journalism and did not go unnoticed. With his youth nearly over, and a

family to support, in mid-1887 Wilde became the editor of The Lady's World magazine, his name prominently appearing on the cover. He promptly renamed it The Woman's World and

raised its tone, adding serious articles on parenting, culture, and

politics, keeping discussions of fashion and arts. Two pieces of

fiction were usually included, one to be read to children, the other

for the ladies themselves. Wilde used his wide artistic acquaintance to

solicit good contributions, including those of Lady Wilde and his wife

Constance, while his own "Literary and Other Notes" were themselves popular and amusing. The

initial vigour and excitement he brought to the job began to fade as

administration, commuting and office life became tedious. His lack of

interest showed in the magazine's declining quality and flagging sales.

Increasingly sending instructions by letter, he began a new period of

creative work and his own column appeared less regularly. The Portrait of Mr. W.H., which he had begun in 1887, was published in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine in July 1889. It is a short story in which a theory that Shakespeare's sonnets were written out of the poet's love of the boy actor "Willie Hughes",

is advanced, retracted, and then propounded again. The only evidence

for this is two supposed puns within the sonnets themselves. The

anonymous narrator is at first sceptical, then believing, finally

flirtatious with the reader. By the end fact and fiction have melded

together. "You must believe in Willie Hughes" he told an acquaintance, "I almost do myself". In October 1889, Wilde had finally found his voice in prose and, at the end of the second volume, Wilde left The Woman's World. The magazine outlasted him by one volume. Wilde,

having tired of journalism, had been busy setting out his aesthetic

ideas more fully in a series of dialogues which were published in the

major literary-intellectual journals of the day. Pen, Pencil and Poison: A Study was published in 1889 by his friend Frank Harris, editor of the Fortnightly Review, while The Decay of Lying: A Dialogue was in Eclectic Magazine in February of the same year. Next Wilde produced his first version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, published as the lead story in the July 1890 edition of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, along with five other novels. Wilde

revised it extensively, adding six new chapters at the behest of his

publisher for publication in book form the following year. It was Wilde's annus mirabilis:

apart from his novel, he also published several collections of earlier

published pieces. His critical prose writings were significantly

revised and packaged as Intentions. Meanwhile two collections of fairy stories for children were published , Lord Arthur Saville's Crime & Other Stories, and in September The House of Pomegranates was dedicated "To Constance Mary Wilde". The 1891 census records the Wildes' residence at 16 Tite Street, where

he lived with his wife Constance and sons. Wilde though, not content

with being more well-known than ever in London, returned to Paris in

October 1891. The success of his stories and novel behind him, his

thoughts had begun to move towards the dramatic form, though it was the

biblical iconography of Salome that filled his head. He was received at the salons littéraires, including the famous mardis of Stéphane Mallarmé, a renowned symbolist poet of the time. One

evening, after discussing his ideas of Salome, he returned to his hotel

to notice a blank copybook lying on the desk, and it occurred to him to

write down what he had been saying. Salomé, written in French, was soon nearly finished. When Wilde left just before Christmas, the Paris Echo newspaper referred to him as "le great event" of the season. Rehearsals, including Sarah Bernhardt began, but the play was refused a licence by the Lord Chamberlain, since it depicted biblical characters. Salomé was

published jointly in Paris and London in 1893, but was not performed

until 1896 in Paris, during Wilde's later incarceration.

In mid-1891 poet Lionel Johnson introduced Wilde to Alfred Douglas,

an undergraduate at Oxford at the time. Known to his family and friends

as "Bosie", he was an handsome and spoilt young man. An intimate

friendship sprang up between Wilde and Douglas, but it was not

initially sexual, nor did the sexual activity progress far when it

eventually took place. According to Douglas, speaking in his old age,

"from the second time he saw me, when he gave me a copy of Dorian Gray which

I took with me to Oxford, he made overtures to me. It was not till I

had known him for at least six months and after I had seen him over and

over again and he had twice stayed with me in Oxford, that I gave in to

him. I did with him and allowed him to do just what was done among boys

at Winchester and Oxford ... Sodomy never took place between us, nor

was it attempted or dreamed of. Wilde treated me as an older one does a

younger one at school". After Wilde realised that Douglas only consented in order to please him, Wilde permanently ceased his physical attentions. Wilde, who had first set out to irritate Victorian society with his dress and talking points, then outrage it with Dorian Gray, his novel of vice hidden beneath art, finally found a way to critique society on its own terms. Lady Windermere's Fan was

first performed on 20 February 1892 at St James Theatre, packed with

the cream of society. On the surface a witty comedy, there is subtle

subversion underneath: "it concludes with collusive concealment rather

than collective disclosure". The

audience, like Lady Windermere, are forced to soften harsh social codes

in favour of a more nuanced view. The play was enormously popular,

touring the country for months, but largely thrashed by conservative

critics. When

Wilde answered the calls of "Author!" and appeared before the curtains

at the end, they were more offended by the cigarette in his hand than

his egoistic speech: Ladies and Gentlemen. I have enjoyed this evening immensely. The actors have given us a charming rendition of a delightful play, and your appreciation has been most intelligent. I congratulate you on the great success of your performance, which persuades me that you think almost as highly of the play as I do myself. It was followed by A Woman of No Importance in

1893, another essentially Victorian comedy: revolving around the

spectre of illegitimate births, mistaken identities and late

revelations. Wilde was commissioned to write two more plays, and An Ideal Husband, written in 1894, followed in January 1895. Peter

Raby said these essentially English plays were well-pitched, "Wilde,

with one eye on the dramatic genius of Ibsen, and the other on the

commercial competition in London's West End, targeted his audience with

adroit precision". Wilde

was now infatuated with Douglas and they began a tempestuous affair,

consorting together regularly. If Wilde was relatively indiscreet, even

flamboyant, in the way he acted, Douglas was reckless in public. Wilde,

who was earning up to £100 a week from his plays (his salary at The Woman's World had

been £6), indulged Douglas's every whim: material, artistic or

sexual. Their relationship was not marked by fidelity, and Douglas soon

dragged Wilde into the Victorian underground of gay prostitution.

Douglas and some Oxford friends began to discuss homosexual-law reform,

"The Cause", and they founded an Oxford journal, The Chameleon, to which Wilde "sent a page of paradoxes originally destined for the Saturday Review". Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young was

to come under attack six months later at Wilde's trial, where he was

forced to defend the magazine to which he had sent his work. In any case, it became unique: The Chameleon was not published again. At

Douglas's encouragement, Wilde stepped up the pace of casual sexual

affairs. Through Douglas he met Alfred Taylor, and they introduced him

to a series of young, working class, male prostitutes from 1892

onwards. These relationships usually took the same form: Wilde would

meet the boy, offer him gifts, dine him privately and then take him to

a hotel room. Unlike Wilde's idealised, pederastic relations with John

Gray, Ross, and Douglas, all of whom remained part of his aesthetic

circle, these consorts were uneducated and knew nothing of literature.

Soon his public and private lives had become sharply divided, in De Profundis he

wrote to Douglas that "It was like feasting with panthers; the danger

was half the excitement ... I did not know that when they were to

strike at me it was to be at another's piping and at another's pay." Lord Alfred's father, The Marquess of Queensberry, was known for his outspoken atheism, brutish manner and creation of the modern rules of boxing. His oldest son, Francis Douglas, Viscount Drumlanrig, possibly had an intimate association with Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery,

the Prime Minister to whom he was private secretary, which ended with

Drumlanrig's death in an unexplained shooting accident. The Marquess of

Queensberry came to believe his sons had been corrupted by older

homosexuals or, as he phrased it in a letter in the aftermath of

Drumlanrig's death: "Montgomerys, The Snob Queers like Rosebery and

certainly Christian Hypocrite like Gladstone and the whole lot of you". Queensberry

confronted Wilde and Lord Alfred on several occasions, but each time

Wilde was able to mollify him. In June 1894, he called to Wilde at 16

Tite Street, without an appointment, and clarified his stance: "I

do not say that you are it, but you look it, and pose at it, which is

just as bad. And if I catch you and my son again in any public

restaurant I will thrash you" to which Wilde responded: "I don't know what the Queensberry rules are, but the Oscar Wilde rule is to shoot on sight". His account in De Profundis was less triumphant, describing Queensberry was epileptic with rage, screaming every insult under the sun. Queensberry only described the scene once, saying Wilde had "shown him the white feather", meaning he had acted cowardly. Though

trying to remain calm, Wilde saw that he was becoming ensnared in a

brutal family quarrel. He did not wish to bear Queensberry's insults,

but he knew to confront him could lead to disaster were his liaisons

disclosed publicly. Wilde's

final play again returns to the theme of switched identities: the

play's two protagonists engage in "bunburying", the maintenance of

alternate personas in the town and country, which allows them to escape

Victorian social mores. The play, universally acknowledged as a riposte to Wilde's boast to André Gide that he had "put my genius into my life, and only my talent into my works" – premiered on St. Valentine's day 1895. Wilde had firmly reached his artistic maturity and rapidly wrote the play in late 1894. Wilde's

professional success mirrored escalation in his feud with Queensberry.

Queensberry had planned to publicly insult Wilde by throwing a bouquet

of spoiling vegetables onto the stage; Wilde was tipped off and had

Queensberry barred from entering the theatre. On the 18 February 1895, the Marquess left his calling card at Wilde's club, the Albemarle, inscribed: "For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite". Wilde,

egged on by Douglas and against the advice of his friends, made a

complaint of criminal libel against the Marquess of Queensberry. The libel trial became a cause célèbre as

salacious details of Wilde's private life with Taylor and Douglas began

to appear in the press. A team of detectives had directed Queensberry's

lawyers (led by Edward Carson QC)

to the world of the Victorian underground. Wilde's association with

blackmailers and male prostitutes, cross-dressers and homosexual

brothels was recorded, and various persons involved were interviewed,

some being coerced to appear as witnesses, since they too were

accomplices to the crimes Wilde was accused of. The

trial opened on the 3 April 1895 amongst scenes of near hysteria both

in the press and the public galleries. The extent of the evidence

massed against Wilde forced him to meekly declare "I am the prosecutor

in this case". Wilde's lawyer, Sir Edward George Clarke,

opened the case by pre-emptively asking Wilde about two suggestive

letters Wilde had written to Douglas, which the defence had. Wilde

stated that the letters had been obtained by blackmailers who

had attempted to extort money from him, but he had refused, suggesting

they should take the £60 offered, "unusual for a prose piece of

that length". He claimed to regard the letters as works of art rather than as something to be ashamed of. On

cross-examination, Queensberry's lawyer, Edward Carson, questioned

Wilde as to how he perceived the moral content of his works. Wilde

handled the cross-examination with characteristic wit and flippancy,

claiming that works of art are not capable of being moral or immoral

but only well or poorly made, and that only "brutes and illiterates,"

whose views on art "are incalcuably stupid" would

make such judgements about art. Carson, a leading barrister at the

time, diverged from the normal practice of asking closed questions. In

seeking to justify Lord Queensberry's description of Wilde as a poseur,

he allowed Wilde to strike poses, which the latter did. Carson

then questioned Wilde about his acquaintances with lower class men, of

half his age, who were either unemployed or worked as servants. Wilde

admitted being on a first-name basis with the men and giving them gifts

of money, fine clothes, drinks, meals at expensive restaurants, and

travel abroad at expensive hotels, but insisted that nothing untoward

had occurred and that the men were merely good friends of his. Carson

repeatedly pointed out that intimate friendship and lavish gifts

between a well-educated gentleman and uneducated men of the lower class were highly unusual, and insinuated that the men were male prostitutes. Wilde replied that he did not believe in social barriers, and that he simply enjoyed the society of young men. In

one critical exchange, Carson asked Wilde whether he had ever kissed a

certain servant boy. Wilde replied, "Oh, dear no. He was a particularly

plain boy – unfortunately ugly – I pitied him for it." Carson

pressed him on the point, repeatedly asking why the boy's ugliness was

relevant. Wilde hesitated, then for the first time became flustered:

"You sting me and insult me and try to unnerve me; and at times one

says things flippantly when one ought to speak more seriously." In his opening speech for the defence, Carson announced that he had located several male prostitutes who

were to testify that they had had sex with Wilde. On the advice of his

lawyers, Wilde then decided to drop the libel prosecution against

Queensberry, since the testimony of the male prostitutes would have

almost certainly justified Queensberry's claim, thus rendering a

conviction impossible and creating an even more tremendous scandal.

Queensberry was found not guilty, as the court declared that

Queensberry's accusation that Wilde was "posing as a Sodomite" was

justified, "true in substance and in fact."

After Wilde left the court, a warrant for his arrest was applied for and served on him at the Cadogan Hotel, Knightsbridge. Robbie Ross found him there with Reginald Turner; both men advised Wilde to go at once to Dover and

try to get a boat to France; his mother advised him to stay and fight

like a man. Wilde, lapsing into inaction, could only say, "The train

has gone. It's too late." Wilde was arrested for "gross indecency" under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. In British legislation of the time, this term implied homosexual acts not amounting to buggery, which was an offence under a separate statute. At

Wilde's instruction, Ross and Wilde's butler forced their way into the

bedroom and library of 16 Tite Street, packing some personal effects,

manuscripts, and letters. Wilde was then imprisoned on remand at Holloway where he received daily visits from Douglas. Events

moved quickly and his prosecution opened on 26 April 1895. Wilde had

already begged Douglas to leave London for Paris, but Douglas

complained bitterly, even wanting to take the stand; however he was

pressed to go and soon fled to the Hotel du Monde. Fearing persecution, Ross and

many other gentlemen also left the United Kingdom during this time.

Under cross examination Wilde was at first hesitant, then spoke

eloquently: Charles Gill (prosecuting): What is "the love that dare not speak its name?" Wilde: "The

love that dare not speak its name" in this century is such a great

affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare.

It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect.

It dictates and pervades great works of art, like those of Shakespeare

and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It

is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be

described as "the love that dare not speak its name," and on that

account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine,

it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about

it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an older and a

younger man, when the older man has intellect, and the younger man has

all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so,

the world does not understand. The world mocks at it, and sometimes

puts one in the pillory for it." The trial ended with the jury unable to reach a verdict and Wilde's counsel, Sir Edward Clark, was finally able to agree bail. Wilde was freed from Holloway and, shunning attention, went into hiding at the house of Ernest and Ada Leverson, two of his firm friends. The Reverend Stewart Headlam put up most of the £5,000 bail, having

disagreed with Wilde's heinous treatment by the press and the courts.

Edward Carson approached Frank Lockwood (QC) and asked "Can we not let

up on the fellow now?" Lockwood

answered that he would like to do so, but feared that the case had

become too politicised to be dropped. The final trial was presided over

by Mr Justice Wills. On 25 May 1895 Wilde and Alfred Taylor were convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to two years' hard labour. The judge described the sentence as "totally inadequate for a case such as

this," although it was the maximum sentence allowed for the charge

under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885. Wilde's response "And I?, May I say nothing my Lord?" was drowned out in cries of "Shame" in the courtroom. Wilde was imprisoned first in Pentonville and then Wandsworth prisons

in London. The regime at the time was tough; "hard labour, hard fare

and a hard bed" was the guiding philosophy. It wore particularly

harshly on Wilde as a gentleman and his status provided him no special

privileges. In

November he was forced to attend Chapel, and there he was so weak from

illness and hunger that he collapsed, bursting his right ear drum, an

injury that would later contribute to his death. He spent two months in the infirmary. Richard B. Haldane, the Liberal MP and reformer, visited him and had him transferred in November to HM's Prison, Reading, 30 miles west of London. The transfer itself was the lowest point of his incarceration, as a crowd jeered and spat at him on the platform. Now

known as prisoner C. 3.3 (Gallery C, 3rd floor, cell three) he was not,

at first, even allowed paper and pen, but Haldane eventually succeeded in allowing access to books and writing materials. Wilde requested, among others: the Bible in French, Italian and German grammars, some Ancient Greek texts, Dante's poetry, En Route, Joris-Karl Huysmans's new French novel about Christian redemption; and essays by St Augustine, Cardinal Newman and Walter Pater. Between

January and March 1897 Wilde wrote a 50,000-word letter to Douglas,

which he was not allowed to send, but was permitted to take with him

upon release. In

it he repudiates Douglas for what Wilde finally sees as his arrogance

and vanity; he had not forgotten Douglas's remark, when he was ill,

"When you are not on your pedestal you are not interesting." He

also felt redemption and fulfilment in his ordeal, realising that his

hardship had filled the soul with the fruit of experience, however

bitter it tasted at the time. ...I

wanted to eat of the fruit of all the trees in the garden of the

world... And so, indeed, I went out, and so I lived. My only mistake

was that I confined myself so exclusively to the trees of what seemed

to me the sun-lit side of the garden, and shunned the other side for

its shadow and its gloom. On

his release, he gave the manuscript to Ross, who may or may not have

carried out Wilde's instructions to send a copy to Douglas (who later

denied having received it). De Profundis was partially published in 1905, its complete and correct publication first occurred in 1962 in The Letters of Oscar Wilde. Wilde

was released on the 19 May 1897; though his health had suffered

greatly, he had a feeling of spiritual renewal. He immediately wrote to

the Jesuits requesting a six-month Catholic retreat; when the request

was denied, Wilde wept. He

left England the next day for the continent, to spend his last three

years in penniless exile. He took the name "Sebastian Melmoth", after Saint Sebastian, and the titular character of Melmoth the Wanderer; a gothic novel by Charles Maturin, Wilde's great-uncle. Wilde wrote two long letters to the editor of the Daily Chronicle, describing the brutal conditions of English prisons and advocating penal reform.

His discussion of the dismissal of Warder Martin, for giving biscuits

to an anaemic child prisoner, repeated the themes of the corruption and

degeneration of punishment that he had earlier outlined in The Soul of Man Under Socialism. Wilde spent mid-1897 with Robert Ross in Berneval-le-Grand, where he wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

The poem narrates the execution of a man who murdered his wife for her

infidelity; it moves from an objective story-telling to symbolic

identification with the prisoners as a whole. No

attempt is made to assess the justice of the laws which convicted them,

but rather the brutalisation of the punishment that all convicts share.

Instead, he juxtaposes the executed man and himself with the line "and

so each man kills the thing he loves"; Wilde

too was separated from his wife and sons. He adopted the proletarian

ballad form, and the author was credited as "C.3.3." He suggested it be

published in Reynold's Magazine,

"because it circulates widely among the criminal classes – to which I

now belong – for once I will be read by my peers – a new experience for

me". It

was a commercial success, going through seven editions in less than two

years, only after which "[Oscar Wilde]" was added to the title page,

though many in literary circles had known Wilde to be the author. It brought him a little money. Although Douglas had been the cause of his misfortunes, he and Wilde were reunited in August 1897 at Rouen.

This meeting was disapproved of by the friends and families of both

men. Constance Wilde was already refusing to meet Wilde or allow him to

see their sons, though she kept him supplied with money. During the

latter part of 1897, Wilde and Douglas lived together near Naples for a few months until they were separated by their respective families under the threat of a cutting-off of funds. Wilde's final address was at the dingy Hôtel d'Alsace (now known as L'Hôtel), in Paris; "This poverty really breaks one's heart: it is so sale, so utterly depressing, so hopeless. Pray do what you can" he wrote to his publisher. He corrected and published An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest, the proofs of which Ellmann argues show a man "very much in command of himself and of the play" but he refused to write anything else "I can write, but have lost the joy of writing". He spent much time wandering the Boulevards alone, and spent what little money he had on alcohol. A

series of embarrassing encounters with English visitors, or Frenchmen

he had known in better days, further damaged his spirit. By the 12

October he was sufficiently confined to his hotel to send a telegram to

Ross: "Terribly weak. Please come." On one of his final trips outside hotel he is quoted as saying, less than a month before his death, "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go." His moods fluctuated; Max Beerbohm relates how, a few days before Wilde's death, their mutual friend Reginald 'Reggie' Turner had

found Wilde very depressed after a nightmare. "I dreamt that I had

died, and was supping with the dead!" "I am sure", Turner replied,

"that you must have been the life and soul of the party." Turner was one of the very few of the old circle who remained with Wilde right to the end, and was at his bedside when he died. By 25 November 1900 Wilde had developed cerebral meningitis and was injected with morphine,

his mind wandering during those periods when he regained consciousness.

Robbie Ross arrived on 29 November and sent for a priest, and Wilde was conditionally baptised into the Roman Catholic church by Fr Cuthbert Dunne, a Passionist priest from Dublin. Fr Dunne recorded the baptism: As the voiture rolled

through the dark streets that wintry night, the sad story of Oscar

Wilde was in part repeated to me....Robert Ross knelt by the bedside,

assisting me as best he could while I administered conditional baptism,

and afterwards answering the responses while I gave Extreme Unction to

the prostrate man and recited the prayers for the dying. As the man was

in a semi-comatose condition, I did not venture to administer the Holy

Viaticum; still I must add that he could be roused and was roused from

this state in my presence. Wilde died of cerebral meningitis on 30 November 1900. Different opinions are given as to the cause of the meningitis; Richard Ellmann claimed it was syphilitic; Merlin Holland,

Wilde's grandson, thought this to be a misconception, noting that

Wilde's meningitis followed a surgical intervention, perhaps a mastoidectomy;

Wilde's physicians, Dr. Paul Cleiss and A'Court Tucker, reported that

the condition stemmed from an old suppuration of the right ear (une ancienne suppuration de l'oreille droite d'ailleurs en traitement depuis plusieurs années) and did not allude to syphilis. Wilde was initially buried in the Cimetière de Bagneux graveyard outside Paris; in 1909 his remains were disinterred to Père Lachaise Cemetery, inside the city. His tomb was designed by Sir Jacob Epstein,

commissioned by Robert Ross, who asked for a small compartment to be

made for his own ashes which were duly transferred in 1950. The

modernist angel depicted as a relief on the tomb was originally

complete with male genitalia which

were broken off by a visitor and subsequently kept as a paperweight by

a succession of cemetery keepers; their current whereabouts are

unknown. In 2000, Leon Johnson, a multi-media artist, installed a

silver prosthesis to replace them. The epitaph is a verse from The Ballad of Reading Gaol: And alien tears will fill for him

Under the snow

Speak gently, she can hear

the daisies grow"

Pity's long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.