<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Marsilio Ficino, 1433

- Pioneer Filmmakers Auguste Marie Louis Nicolas et Louis Jean Lumière, 1862 1864

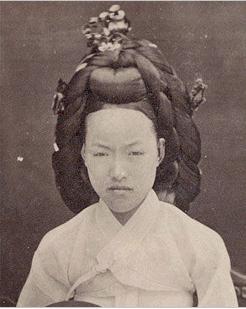

- Empress of Korea Myeongseong, 1851

PAGE SPONSOR

Empress Myeongseong (19 October 1851 – 8 October 1895), also known as Queen Min, was the first official wife of King Gojong, the twenty-sixth king of the Joseon dynasty of Korea. In 1902, she received the posthumous name Hyoja Wonseong Jeonghwa Hapcheon Honggong Seongdeok Myeongseong Taehwanghu, often abbreviated as Myeongseong Hwanghu, meaning Empress Myeongseong.

The Japanese considered her as an obstacle against its overseas expansion. Efforts to remove her from the political arena, orchestrated through failed rebellions prompted by the father of King Gojong, Heungseon Daewongun (an influential regent working with the Japanese), compelled the Empress to take a harsher stand against Japanese influence. After Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War,

Queen Min advocated stronger ties between Korea and Russia in an

attempt to block Japanese influence in Korea, which was represented by

the Daewongun. Miura Gorō,

the Japanese Minister to Korea at the time and a retired army

lieutenant-general, backed the faction headed by the Daewongun, whom he

considered to be more sympathetic to Japanese interests. In the early

morning of 8 October 1895, sword-bearing assassins allegedly under

orders from Miura Gorō entered Gyeongbok Palace.

Upon entering the Queen's Quarters (Okhoru), the assassins "killed

three court [women] suspected of being Empress Myeongseong. When they

confirmed that one of them was the Empress, they burned the corpse in

the pine forest in front of the Okhoru complex of the immense palace,

and then dispersed the ashes." Queen Min was 43. The assassination of the Korean Empress ignited diplomatic protest abroad. To appease growing international criticism, the

Japanese government "recalled Miura and placed him under a staged trial

at the Hiroshima District Court, while the military personnel involved

were tried at the military court. All were given the verdict of not

guilty on the grounds of insufficient evidence." After the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, Miura was honored and awarded a seat at the Privy Council (Sumitsuin), the advisory board to the Emperor. The Empress's role has been widely debated by historians. Some Koreans who survived the Japanese occupation criticize

her for failing to militarily resist the Japanese. The Japanese

portrayal of Empress Myeongseong forms part of the recent controversy

over allegations of revisionist history in Japanese school textbooks. In South Korea, there is renewed interest in her life because of recent novels, TV drama and musical.

In Korea she is viewed by many as a national heroine, for striving

diplomatically and politically to keep Korea independent of foreign

influence. She had planned to modernize Korea. In 1864, King Cheoljong was

dying and there were no male heirs, the result of suspected foul play

by a rival branch of the royal family, the Andong Kim clan. The Andong

Kim clan had risen to power through intermarriage with the royal Yi

family. Queen Cheolin, the queen consort of Cheoljong and a member of

the Andong Kim clan, claimed the right to choose the next king,

although traditionally, the eldest queen dowager is the one with the

authority to select the new king. Cheoljong’s cousin, Grand Royal Dowager Queen Sinjeong (the widow of Heonjong's

father [entitled Ikjong]) of the Pungyang Jo clan, who too had risen to

prominence by intermarriage with the Yi family, currently held this

title. Sinjeong

saw an opportunity to advance the cause of the Pungyang Jo clan, the

only true rival of the Andong Kim clan in Korean politics. As Cheoljong

fell deeper under his illness, the Grand Royal Dowager Queen was

approached by Yi Ha-eung, an obscure descendant of King Yeongjo, through his son Crown Prince Sado. The

branch that Yi Ha-eung's family belonged to was an obscure line of

descent of the Yi clan, which survived the often deadly political

intrigue that frequently embroiled the Joseon court by forming no

affiliation with any factions. Yi Ha-eung himself was ineligible for

the throne due to a law that dictated that any possible heir to the

kingdom be part of the generation after the most recent incumbent of

the throne, but Yi Myeong-bok, Yi Ha-eung's second son (the future King Gojong and Gwangmu Emperor), was a possible successor to the throne. The

Pungyang Jo clan saw that Yi Myeong-bok was only twelve years old and

would not be able to rule in his own name until he came of age, and

that they could easily influence Yi Ha-eung, who would be acting as

regent for the to-be boy king. As soon as news of Cheoljong's death

reached Yi Ha-eung through his intricate network of spies in the

palace, he and the Pungyang Jo clan took the hereditary royal seal (an

object that was considered necessary for a legitimate reign to take

place and aristocratic recognition to be received) —- effectively

giving her absolute power to select the successor to the throne. By the

time Cheoljong's death had become a known fact, the Andong Kim clan was

powerless according to law as the seal lay in the hands of the Grand

Royal Dowager Queen Sinjeong. In the autumn of 1864, Yi Myeong-bok was

crowned the new King of the Kingdom of Joseon, with his father entitled

as the Heungseon Daewongun (Daewongun; Grand Internal Prince). The strongly Confucian Heungseon Daewongun proved

to be a wise and calculating leader in the early years of Gojong's

reign. He abolished the old government institutions that had become

corrupt under the rule of various clans, revised the law codes along

with the household laws of the royal court and the rules of court

ritual, and heavily reformed the military techniques of the royal

armies. Within a few short years, he was able to secure complete

control of the court and eventually receive the submission of the

Pungyang Jos while successfully disposing the last of the Andong Kims,

whose corruption, he believed, was responsible for ruining the country. The future empress was born into the aristocratic Min family of Yeoheung on 19 October 1851 in Yeoju-gun, in the province of Gyeonggi (where the clan originated). The

Yeoheung Mins were a noble clan, boasting of many highly positioned

bureaucrats in its illustrious past, even having three queens. The

first, Queen Wongyeong, was the wife of the third king of the Joseon Dynasty, Taejong; the second, Queen Inhyeon, was the wife of the nineteenth king, Sukjong. Daewongun's mother and wife, both of whom were from the Min family, recommended Myeongseong as the queen. The daughter of Min Chi-rok is how Empress Myeongseong was known before her marriage. Some fictional accounts name her Min Ja-yeong but this tradition has not been confirmed by historical sources. At the age of eight she had lost both of her parents. Little is known of her mother, her childhood, or the causes of her parents' early deaths. When

Gojong reached the age of 15, his father decided it was time for him to

be married. He was diligent in finding a queen without close relatives,

who would harbour political ambitions and yet have a noble lineage, in

order to justify his choice to the court and the people. Candidates

were rejected one by one, until the wife of Daewongun (Yeoheung, the

Princess Consosrt to the Prince of the Great Court; Yeoheung Budaebuin) proposed a bride from her own clan (the Yeoheung Mins). His

wife's description of the girl was quite persuasive: orphaned,

beautiful features, healthy body, ordinary level of education (no less

than that of the most noble in the country). The first meeting of the

proposed bride with the Daewongun was easily arranged as she lived in

the nearby Anguk-dong neighborhood. Their meeting was a success, and on 20 March 1866, the future Queen (and later Empress Myeongseong) married the boy king. Their wedding took place at the Injeong Hall at Changdeok Palace. It

is known that the wig (which was usually worn by royal brides at

weddings) was so heavy that a tall court lady was specially assigned to

support it from the back. The wedding ceremony was barely finished when

another three-day ceremony for the reverencing of the ancestors started. In

the coronation ceremony the girl, barely sixteen, was invested as the

Queen of Joseon, and ascended the throne with her husband. She was

styled as Her Royal Highness, Queen Min (Min Daebi, Queen Min). After she became the queen, she was called "Her Majesty, the Central Hall" (jungjeon mama). She

was an assertive and ambitious woman, unlike other queens that came

before her. She did not participate in lavish parties, rarely

commissioned extravagant fashions from the royal ateliers, and almost

never hosted afternoon tea parties with the powerful aristocratic

ladies and princesses of the royal family, unless politics beckoned her

to. As Queen, she was expected to act as icon to the high society of

Korea, but Min rejected this belief. She, instead, read books reserved

for men (examples of which were Spring and Autumn Annals and Commentary of Zuo), and taught herself philosophy, history, science, politics and religion. Even

without parents, Min was able to secretly form a powerful faction

against Heungseon Daewongun as soon as she reached adulthood. At the

age of twenty, she began to wander outside her apartments at Changgyeonggung and

play an active part in politics. At the same time, the to-be (although

not yet titled) Queen defended her views against high officials who

viewed her as becoming meddlesome. Heungseon Daewongun was also upset

by the Queen's aggressiveness. The

political struggle between Min and Heungseon Daewongun became public

when the son she bore for Gojong died prematurely. Heungseon Daewongun

publicly stated that Min was unable to bear a healthy male child and

directed Gojong to have intercourse with a royal concubine, Yeongbodang

Yi. In 1880, the concubine gave birth to a healthy baby boy, Prince

Wanhwagun, whom Heungseon Daewongun titled Crown Prince. Min

responded with a powerful faction of high officials, scholars, and

members of her clan to bring down Heungseon Daewongun from power. The

to-be (again, she was not referred to this at the time) Queen’s

relative, Min Seung-ho, with court scholar Choe Ik-hyeon,

wrote a formal impeachment of Heungseon Daewongun to be presented to

the Royal Council of Administration, arguing that Gojong, now

twenty-two, should rule in his own right. With the approval of Gojong

and the Royal Council, Heungseon Daewongun was forced to retire to his

estate at Yangju in

1872, the smaller Unhyeongung. The to-be Empress then banished the

royal concubine and her child to a village outside the capital,

stripped of royal titles. The child soon died afterwards, with some

accusing Min of involvement. With

the retirement of Heungseon Daewongun and the expelled concubine and

her son, the to-be Queen gained complete control over her court,

placing her family in high court positions. This action proved that Min

was the Queen of Korea, who ruled with her husband, King Gojong, but

was distinctly more politically active than he was. After

the Korean refusal to receive Japanese envoys announcing the Meiji

Restoration, some Japanese aristocrats favored an immediate invasion of

Korea, but the idea was quickly dropped upon the return of the Iwakura

Mission on the grounds that the new Japanese government was neither

politically nor fiscally stable enough to start a war. When Heungseon

Daewongun was ousted from politics, Japan renewed efforts to establish

ties with Korea, but the Imperial envoy arriving at Dongnae in 1873 was turned away. The Japanese government, which sought to emulate the empires of Europe in their tradition of enforcing so-called Unequal Treaties, responded by sending the Japanese battleship Unyō towards Busan and another battleship to the Bay of Yeongheung on the pretext of surveying sea routes, meaning to pressure Korea into opening its doors. The Unyō ventured into restricted waters of Ganghwa Island, provoking an attack from Korean shore batteries. The Unyō fled

but the Japanese used the incident as a pretext to force a treaty on

the Korean government. In 1876 six naval vessels and an imperial

Japanese envoy were sent to Ganghwa Island to enforce this command. A

majority of the royal court favored absolute isolationism, but Japan

had demonstrated its willingness to use force. After numerous meetings,

officials were sent to sign the Ganghwa Treaty,

a treaty that had been modeled after treaties imposed on Japan by the

United States. The treaty was signed on 15 February 1876, thus opening

Korea to Japan. Various

ports were forced to open to Japanese trade, and Japanese now had

rights to buy land in designated areas. The treaty also permitted the

opening of Incheon and Wonsan to

Japanese merchants. For the first few years, Japan enjoyed a near total

monopoly of trade, while Korean merchants suffered serious losses. In 1877, a mission headed by Kim Gwang-jip was

commissioned by Gojong and Min to study Japanese westernization and

intentions for Korea. Kim and his team were shocked at how large the

Japanese cities had become. Kim Gi-su noted that only fifty years ago, Seoul and Busan of Korea were metropolitan centers of East Asia, towering over underdeveloped Japanese cities; but now, with Tokyo and Osaka

completely westernized, Seoul and Busan looked like vestiges of the

ancient past. When they were in Japan, Kim Gwang-jip met with the

Chinese Ambassador to Tokyo, Ho Ju-chang and the councilor Huang Tsun-hsien. They discussed the international situation of Qing China and Joseon's place in the rapidly changing world. Huang Tsu-hsien presented to Kim a book he had written called Korean Strategy. China

was no longer the hegemonic power of East Asia, and Korea no longer

enjoyed military superiority over Japan. In addition, the Russian

Empire began expansion into Asia. Huang advised that Korea should adopt

a pro-Chinese policy, while retaining close ties with Japan for the

time being. He also advised an alliance with the United States for

protection against Russia. He advised opening trade relations with

Western nations and adopting Western technology. He noted that China

had tried but failed due to its size, but Korea was smaller than Japan.

He viewed Korea as a barrier to Japanese expansion into mainland Asia.

He suggested Korean youths be sent to China and Japan to study, and

Western teachers of technical and scientific subjects be invited to

Korea. When

Kim Gwang-jip returned to Seoul, Min took special interest in Huang's

book and commissioned copies be sent out to all the ministers. Min

hoped to win yangban approval to invite Western nations into Korea. She

wanted to first allow Japan to help in the modernization process but

towards completion of certain projects, be driven out by Western

powers. She intended for Western powers to begin trade and investment

in Korea to keep Japan in check. However, the yangban still opposed opening the country to the West. Choe Ik-hyeon, who had helped with the impeachment of Heungseon Daewongun,

sided with the isolationists, saying that the Japanese were just like

the “Western barbarians” who would spread subversive notions like Catholicism (which had been a major issue during Heungseon Daewongun's reign that ended in massive persecution). To

the scholars and the yangban, Min's plan meant the destruction of

social order. The response to the distribution of “Korean Strategy” was

a joint memorandum to the throne from scholars in every province of the

kingdom. They stated that the ideas in the book were mere abstract

theories, unrealizable in practice, and that the adoption of Western

technology was not the only way to enrich the country. They demanded

that the number of envoys exchanged, ships engaged in trade and

articles of trade be strictly limited, and that all foreign books in

Korea should be destroyed. Despite

these objections, in 1881, a large fact-finding mission was sent to

Japan to stay for seventy days observing Japanese government offices,

factories, military and police organizations, and business practices.

They also obtained information about innovations in the Japanese

government copied from the West, especially the proposed constitution.

On

the basis of these reports, Min began the reorganization of the

government. Twelve new bureaus were established that dealt with foreign

relations with the West, China, and Japan. Other bureaus were

established to effectively deal with commerce. A bureau of the military

was created to modernize weapons and techniques. Civilian departments

were also established to import Western technology. In the same year,

Min signed documents for top military students to be sent to Qing China.

The Japanese quickly volunteered to supply military students with

rifles and train a unit of the Korean army to use them. Queen Min

agreed but reminded the Japanese that the students would still be sent

to China for further education on Western military technologies. The

modernization of the military was met with opposition. The special

treatment of the new training unit caused resentment among the other

troops. In September 1881, a plot was uncovered to overthrow Min’s

faction, depose Gojong, and place Heungseon Daewongun's illegitimate

(third) son, Yi Jae-seon on

the throne. The plot was frustrated by Min but Heungseon Daewongun was

kept safe from persecution because he was the father of the King. In

1882, members of the old military became so resentful of the special

treatment of the new units that they attacked and destroyed the house of Min Gyeom-ho,

a relative of the Queen who was the administrative head of the training

units. These soldiers then fled to Heungseon Daewongun, who publicly

rebuked but privately encouraged them. Heungseon Daewongun then took

control of the old units. He ordered an attack on the administrative district of Seoul that housed the Gyeongbokgung,

the diplomatic quarter, military centers, and science institutions. The

soldiers attacked police stations to free comrades who had been

arrested and then began the ransacking of private estates and mansions

of the relatives of the Queen. These units then stole rifles and began

to kill Japanese training officers, narrowly missed killing the

Japanese ambassador to Seoul, who quickly escaped to Incheon.

The military rebellion then headed towards the palace but Queen Min and

the King escaped in disguise and fled to her relative’s villa in Cheongju, where they remained in hiding. Numerous

supporters of Queen Min were put to death as soon as Heungseon

Daewongun arrived and took administrative control of Gyeongbokgung. He

immediately dismantled the reform measures implemented by Min and

relieved the new units of their duty. Foreign policy quickly turned

isolationist, and Chinese and Japanese envoys were forced out of the

capital. Li Hung-chang, with the consent of Korean envoys in Beijing,

sent 4,500 Chinese troops to restore order, as well as to secure

Chinese interest in Korean politics. The troops arrested Heungseon

Daewongun, who was taken to China to be tried for treason. Min and her

husband returned and overturned all of Heungseon Daewongun's actions. The

Japanese forced King Gojong privately, without Min's knowledge, to sign

a treaty on 10 August 1882, to pay 550,000 yen for lives and property

that the Japanese had lost during the insurrection, and permit Japanese

troops to guard the Japanese embassy in Seoul. When Min learned of the

treaty, she proposed to China a new trade agreement, granting the

Chinese special privileges and rights to ports inaccessible to the

Japanese. Min also requested that a Chinese commander take control of

the new military units and a German adviser named Paul George von Moellendorff to head the Maritime Customs Service.

In

September 1883, Min established English language schools with American

instructors. Min sent a special mission to the United States headed by Min Yeong-ik, a relative of the Queen, in July 1883. The mission arrived at San Francisco carrying

the newly created Korean national flag, visited many American

historical sites, heard lectures on American history, and attended a

gala event in their honor given by the mayor of San Francisco and other

U.S. officials. The mission dined with President Chester A. Arthur and

discussed the growing threat of Japan and American investment in Korea.

At the end of September, Min Young-ik returned to Seoul and reported to

the Queen, "I was born in the dark. I went out into the light, and your

Majesty, it is my displeasure to inform you that I have returned to the

dark. I envision a Seoul of towering buildings filled with Western

establishments that will place herself back above the Japanese

barbarians. Great things lie ahead for the Kingdom, great things. We

must take action, your Majesty, without hesitation, to further

modernize this still ancient kingdom." The

Progressives were founded during the late 1870s by a group of yangban

who fully supported Westernization of Joseon. However, they wanted

immediate Westernization, including a complete cut-off of ties with Qing China.

Unaware of their anti-Chinese sentiments, the Queen granted frequent

audiences and meetings with them to discuss progressivism and

nationalism. They advocated for educational and social reforms,

including the equality of the sexes by granting women full rights,

issues that were not even acknowledged in their already Westernized

neighbor of Japan. Min was completely enamored by the Progressives in

the beginning, but when she learned that they were deeply anti-Chinese,

Min quickly turned her back on them. Cutting ties with China

immediately was not in Min's gradual plan of Westernization. She saw

the consequences Joseon would have to face if she did not play China

and Japan off by the West gradually, especially since she was a strong

advocate of the Sadae faction who were pro-China and pro-gradual

Westernization. However,

in 1884, the conflict between the Progressives and the Sadaes

intensified. When American legation officials, particularly Naval

Attaché George C. Foulk, heard about the growing problem, they

were outraged and reported directly to the Queen. The Americans

attempted to bring the two groups to peace with each other in order to

aid the Queen in a peaceful transformation of Joseon into a modern

nation. After all, she liked the ideas and plans of both parties. As a

matter of fact, she was in support of many of the Progressive's ideas,

except for severing relations with China. However,

the Progressives, fed up with the Sadaes and the growing influence of

the Chinese, sought the aid of the Japanese legation guards and staged

a bloody palace coup on 4 December 1884. The Progressives killed

numerous high Sadaes and secured key government positions vacated by

the Sadaes who had fled the capital or had been killed. The

refreshed administration began to issue various edicts in the King and

Queen's names and they were eager to implement political, economic,

social, and cultural reforms. Queen Min, however, was horrified by the

bellicosity of the Progressives and refused to support their actions

and declared any documents signed in her name to be null and void.

After only two days of new influence over the administration, they were

crushed by Chinese troops under Yuan Shih-kai's

command. A handful of Progressive leaders were killed. Once again, the

Japanese government saw the opportunity to extort money out of the

Joseon government by forcing King Gojong, again without the knowledge of the Queen, to sign a treaty. The Hanseong Treaty forced Joseon to pay a large sum of indemnity for damages inflicted on Japanese lives and property during the coup. On 18 April 1885 the Li-Ito Agreement was

made in Tianjin, China between the Japanese and the Chinese. In it,

they agreed to both pull troops out of Joseon and that either party

would send troops only under condition of their property being

endangered and that each would inform the other before doing so. Both

nations also agreed to pull out their military instructors to allow the

newly arrived Americans to take full control of that duty. The Japanese

withdrew troops from Korea, leaving a small number of legation guards,

but Queen Min was ahead of the Japanese in their game. She summoned

Chinese envoys and through persuasion, convinced them to keep 2,000

soldiers disguised as Joseon police or merchants to guard the borders

from any suspicious Japanese actions and to continue to train Korean

troops. Peace

finally settled upon the once-renowned "Land of the Morning Calm." With

the majority of Japanese troops out of Joseon and Chinese protection

readily available, the plans for further, drastic modernization were

continued. Plans to establish a palace school to educate children of

the elite had been in the making since 1880 but were finally executed

in May 1885 with the approval of Queen Min. A palace school named Yugyoung Kung-won was established, with an American missionary, Dr. Homer B. Hulbert,

and three other missionaries to lead the development of the curriculum.

The school had two departments, liberal education and military

education. Courses were taught exclusively in English using English textbooks. Queen

Min also gave her patronage to the first all girls' educational

institution, Ewha Academy established in Seoul, 1886 by American

missionary, Mary F. Scranton, now known under the name of Ewha University.

In 1887, Queen personally gave the name "Ewha" (literally "pear

blossom"), the symbol of the Korean royal house and sent a tablet to

encourage Ms. Scranton's effort and its future. Ms. Scranton accepted

the bestowed name to correspond to the Queen's grace. This was the

first time in history that any Korean girl, commoner or aristocratic,

had the right to an education. This was a significant social change. The Protestant missionaries contributed much to the development of Western education in Joseon. Queen Min, unlike Heungseon Daewongun who

had oppressed Christians, invited different missionaries to enter

Joseon. She knew and valued their knowledge of Western history,

science, and mathematics and was aware of the advantage of having them

within the nation. Unlike the Isolationists, she saw no threat to the

Confucian morals of Korean society by the advent of Christianity. Religious tolerance was another one of Queen Min's goals. The first newspaper to be published in Joseon was the Hanseong sunbo, an all-Hanja newspaper. It was published as a thrice monthly official government gazette by the Pangmun-guk,

an agency of the Foreign Ministry. It included contemporary news of the

day, essays and articles about Westernization, and news of further

modernization of Joseon. In January 1886, the Pangmun-guk published a new newspaper named the Hanseong Jubo (The Seoul Weekly).

The publication of a Korean-language newspaper was a significant

development, and the paper itself played an important role as a

communication media to the masses until it was abolished in 1888 under

pressure from the Chinese government. A newspaper in entirely Hangul, disregarding the Korean Hanja script, was not published until 1894. Ganjo Shimpo (The Seoul News) was published as a weekly newspaper under the patronage of Queen Min and King Gojong, it was written half in Korean and half in Japanese. The arrival of Dr. Horace N. Allen under

invitation of Queen Min in September 1884 marked the official beginning

of Christianity rapidly spreading in Joseon. He was able, with the

Queen's permission and official sanction, to arrange for the

appointment of other missionaries as government employees. He also

introduced modern medicine in Korea by establishing the first western Royal Medical Clinic of Gwanghyewon in February 1885. In

April 1885, a horde of Christian missionaries began to flood into

Joseon. The Isolationists were horrified and realized they had finally

been defeated by Queen Min. The doors to Joseon were not only open to

ideas, technology, and culture, but even to other religions. Having

lost immense power with Heungseon Daewongun still in China as captive, the Isolationists could do nothing but simply watch. Dr. and Mrs. Horace G. Underwood, Dr. and Mrs. William B. Scranton, and Dr. Scranton's mother, Mary Scranton, made Joseon their new home in May 1885. They established churches within Seoul and began to establish centers in the countrysides. Catholic missionaries arrived soon afterwards, reviving Catholicism which had witnessed massive persecution in 1866 under Heungseon Daewongun's rule. While

winning many converts, Christianity made significant contributions

towards the modernization of the country. Concepts of equality, human

rights and freedom, and the participation of both men and women in

religious activities, were all new to Joseon. Queen Min was ecstatic at

the prospect of integrating these values within the government. After

all, they were not just Christian values but Western values in general.

The Protestant missions introduced also Christian hymns and other

Western songs which created a strong impetus to modernize Korean ideas

about music. Queen Min had wanted the literacy rate to rise, and with

the aid of Christian educational programs, it did so significantly

within a matter of a few years. Drastic

changes were made to music as well. Western music theory partly

displaced the traditional Eastern concepts. The organ and other Western

musical instruments were introduced in 1890, and a Christian hymnal, Chansongga, was published in Korean in 1893 under the commission of Queen Min. She herself, however, never became a Christian,

but remained a devout Buddhist with influences from shamanism and

Confucianism; her religious beliefs would become the model, indirectly,

for those of many modern Koreans, who share her belief in pluralism and religious tolerance. Modern

weapons were imported from Japan and the United States in 1883. The

first military factories were established and new military uniforms

were created in 1884. Under joint patronage of Queen Min and King Gojong, a request was made to the US for

more American military instructors to speed up the military

modernization of Korea. Out of all the projects that were going on

simultaneously, the military project took the longest. To manage these

simultaneous projects was in itself a major accomplishment for any

nation. Not even Japan had modernized at the rate of Joseon, and not

with as many projects going on at once, a precursor to modern Korea as

one of East Asia's Tigers in rapid development into a first class

nation during the 1960s - 1980s. In October 1883, American minister Lucius Foote arrived

to take command of the modernization of Joseon's older army units that

had not started Westernizing. In April 1888, General William McEntyre Dye and two other military instructors arrived from the US,

followed in May by a fourth instructor. They brought about rapid

military development. A new military school was created called Yeonmu Gongwon, and an officers training program began. However, despite armies becoming more and more on par with the Chinese and the Japanese, the idea of a navy was

neglected. As a result, it became one of the few failures of the

modernization project. Due to the neglect of developing naval defence,

Joseon's sea borders were open to invasion. It was an ironic mistake

since only a hundred years earlier, Joseon's navy was the strongest in

all of East Asia,

having been the first nation in the world to develop massive iron-clad

warships equipped with cannons. Now, Joseon's navy was nothing but

ancient ships that could barely defend themselves from the advanced

ships of modern navies. However,

for a short while, hope for the military of Joseon could be seen. With

rapidly growing armies, Japan herself was becoming fearful of the

impact of Joseon troops if her government did not interfere soon to

stall the process. Following

the opening of all Korean ports to the Japanese and Western merchants

in 1888, contact and involvement with outsiders and increased foreign

trade rapidly. In 1883, the Maritime Customs Service was established

under the patronage of Queen Min and the supervision of Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet of the United Kingdom. The Maritime Customs Service administered the business of foreign trade and the collection of tariff. By

1883, the economy was now no longer in a state of monopoly conducted by

the Japanese as it had been only a few years ago. The majority was in

control by the Koreans while portions were distributed between Western

nations, Japan, and China. In 1884, the first Korean commercial firms,

such as the Daedong and the Changdong companies, emerged. The Bureau of Mint also produced a new coin called tangojeon in 1884, securing a stable Korean currency at the time. Western investment began to take hold as well in 1886. The German A.H. Maeterns, with the aid of the Department of Agriculture of the US, created a new project called "American Farm" on a large plot of land donated by Queen Min to promote modern agriculture. Farm implements, seeds, and milk cows were imported from the United States. In June 1883, the Bureau of Machines was established and steam engines were imported. However, despite the fact that Queen Min and King Gojong brought

the Korean economy to an acceptable level to the West, modern

manufacturing facilities did not emerge due to a political

interruption: the assassination of Queen Min. Be that as it may,

telegraph lines between Joseon, China, and Japan were laid between 1883

and 1885, facilitating communication. Both the The National Assembly Library of Korea and records kept by Lilias Underwood,

an American missionary who came to Korea in 1888 and was appointed the

Queen’s doctor (she enjoyed the Empress' full trust and intimate

friendship), left very sincere and vivid descriptions of the Queen. Both

described what the Empress looked like, what her voice sounded like,

and her public manner. She was said to have had a soft face with strong

features, a classic pretty but far from the sultry taste Gojong enjoyed.

Her speaking voice was soft and warm, but when conducting affairs of

the state, she would immediately assert her points with strength. Her

public manner was also formal and heavily adhered to court etiquette

and traditional law. Underwood described the Empress in the following: According

to Korean custom, she carried a number of filigree gold ornaments

decorated with long silk tassels fastened at her side. So simple, so

perfectly refined were all her tastes in dress, it is difficult to

think of her as belonging to a nation called half civilized...Slightly

pale and quite thin, with somewhat sharp features and brilliant

piercing eyes, she did not strike me at first sight as being beautiful,

but no one could help reading force, intellect and strength of

character in that face... To put it simply, Gojong and

the young Min did not get along at first. Both found each other's ways

repulsive, Min preferring to stay within her chambers studying, Gojong enjoying

his days and nights drinking and attending banquets and royal parties.

The two, in the beginning, were incompatible. Min was genuinely

concerned with the affairs of the state, immersing herself within

philosophy, history, and science books that were normally reserved for yangban men. She once remarked to a close friend, "He disgusts me." Court

officials remarked that when Min ascended the throne, she was extremely

exclusive in choosing who she associated with and confided with. In

this remark, her relationship with the royal court from the very

beginning strongly resembles the relationship of Marie Antoinette with

her court. Both women found court etiquette restricting but both women

strictly adhered themselves to traditional laws to impress and to gain

respect of the aristocracy. Both women also did not consummate their

marriage on their wedding night, as court tradition dictated them to.

Adding onto their frustrations, both women found immense difficulty in

conceiving a healthy heir. Min's first attempt ended in despair and

humilitation; she conceived a male heir but he shortly died after his

birth due to poor health. Her second attempt found success, but Sunjong was never a healthy child, often catching illnesses and lying in bed for weeks. Both Marie Antoinette and

Min also never were able to truly connect and fall in love with their

husbands until their times of troubles brought them together. In the

end, both women were destined for tragic endings; one being

guillitioned by her people, misunderstood and her name wrongly

distorted; the other brutally assassinated by the Japanese. Min and Gojong began to grow affections for each other during their later years. Gojong was pressured by his advisers to take control of the government and administer his nation. However, one has to remember that Gojong was

not chosen to become King because of his acumen (which he lacked

because he was never formally educated) or because of his bloodline

(which was mixed with courtesan and common blood), but because the Jo

clan had falsely assumed they could control the boy through his father.

When it was actually time for Gojong to

assume his responsibilities of the state, he often needed the aid of

his wife, Min, to conduct international and domestic affairs. In this, Gojong grew

an admiration for his wife's wit, intelligence, and ability to learn

quickly. As the problems of the kingdom grew bigger and bigger, Gojong relied even more on his wife, she becoming his rock during times of frustration. During the years of modernization of Joseon, it is safe to assume that Gojong was

finally in love with his wife. They both began to spend an immense

amount of time with each other, privately and officially. They shared

each other's problems, celebrated each other's joys, and felt each

other's pains. They finally became husband and wife. His affection for her was undying and it has been noted that after the death of Min, Gojong locked

himself up in his chambers for weeks and weeks, refusing to assume his

duties. When he finally did, he lost the will to even try and signed

away treaty after treaty that was proposed by the Japanese, giving the

Japanese immense power. When Heungseon Daewongun was

able to take back some political power after the death of Min, he

presented a proposal with the aid of certain Japanese officials to

lower Min's status as Empress all the way to commoner in her death. Gojong,

a man who had always been used by others and never used his own voice

for his own causes, was noted by scholars as having said, "I would

rather slit my wrists and let them bleed than disgrace the woman who

saved this kingdom." In an act of defiance, he refused to sign Heungseon Daewongun's and the Japanese proposal, and turned them away. The

Eulmi Incident is the term used for the assassination of Empress

Myeongseong which occurred in the early hours of 8 October 1895 at

Okho-ru in the Geoncheonggung, which was rear private royal residence

within Gyeongbokgung Palace. In early hours of 8 October 1895, Japanese agents under Miura Goro carried out the assassination. Miura had orchestrated this incident with the Japanese, Okamoto Ryūnosuke, Sugimura Fukashi, Kunitomo Shigeaki, Sase Kumadestu, Nakamura Tateo, Hirayama Iwahiko, and over 50 other Japanese men. They were said to also have collaborated with Pro-Japanese general U Beom-seon and Yi Du-hwang. In front of Gwanghwamun, the assassins battled the Korean Royal Guards led by Hong Gye-hun and An Gyeong-su. Hong Gye-hun and Minister Yi Gyeong-jik

were subsequently killed in battle and the assassins proceeded to the

Okhoru in Geoncheonggung and killed Empress Myeongseong. The corpse of

the Empress was then burned and buried. The Gabo Reform and assassination of Empress Myeongseong generated anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea; also, it caused some Confucian scholars, as well as farmers, to form over 60 successive righteous armies to fight for Korean freedom on the Korean peninsula. After the assassination of Empress Myeongseong, King Gojong and Crown Prince (Later Emperor Sunjong) fled for refuge to the Russian legation in 11 February 1896. Also, King Gojong declared the Eulmi Four Traitors.

However, In 1897, King Gojong, yielding to rising pressure from both

overseas and the demands of the Independence Association led public

opinion, returned to Gyeongungung (modern-day Deoksugung). There, he proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire.

However, after Japan's victories in the Sino-Japanese and

Russo-Japanese Wars, Korea succumbed to Japanese colonial rule between

1910 and 1945. In May 2005, 84 year old Tatsumi Kawano, the grandson of Kunitomo Shigeaki, paid his respects to Empress Myeongseong at her tomb in Namyangju, Gyeonggi, South Korea. He apologized to Empress Myeongseong's tomb on behalf of his grandfather.

“ I

wish I could give the public a true picture of the queen as she

appeared at her best, but this would be impossible, even had she

permitted a photograph to be taken, for her charming play of expression

while in conversation, the character and intellect which were then

revealed, were only half seen when the face was in repose. She wore her

hair like all Korean ladies, parted in the center, drawn tightly and

very smoothly away from the face and knotted rather low at the back of

the head. A small ornament...was worn on the top of the head fastened

by a narrow black band. Her majesty seemed to care little for

ornaments, and wore very few. No Korean women wear earrings, and the

queen was no exception, nor have I ever seen her wear a necklace, a

brooch, or a bracelet. She must have had many rings, but I never saw

her wear more than one or two of European manufacture... ”