<Back to Index>

- Physician Thomas Bartholin, 1616

- Painter Aelbert Jacobsz Cuyp, 1620

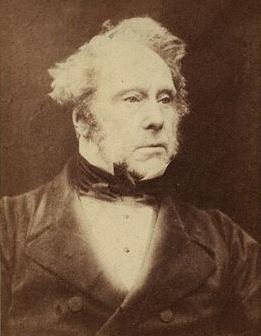

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, 1784

PAGE SPONSOR

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, more popularly known simply as Lord Palmerston KG, GCB, PC (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Popularly nicknamed "Pam", he was in government office almost continuously from 1807 until his death in 1865, beginning his parliamentary career as a Tory and concluding it as a Liberal.

He is best remembered for his direction of British foreign policy through a period when the United Kingdom was at the height of its power, serving terms as both Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister. Some of his aggressive actions, now sometimes termed liberal interventionist, were greatly controversial at the time, and remain so today. He was the last Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to die in office.

Henry John Temple was born in his family's Westminster house to the Irish branch of the Temple family on the 20th of October 1784. He was educated at Harrow School, the University of Edinburgh, and St John's College, Cambridge, he

succeeded his father to the title of Viscount Palmerston on 17 April

1802, before he had turned 18. Over the next 6 years he was defeated in

two elections for the University of Cambridge constituency, but entered parliament as Tory MP for the pocket borough of Newport on the Isle of Wight in June 1807. Thanks to the patronage of Lord Chichester and Lord Malmesbury, he was given the post of Junior Lord of the Admiralty in the ministry of the Duke of Portland. A few months later, he delivered his first speech in the House of Commons in defence of the Battle of Copenhagen (1807), which he justified by reference to the ambitions of Napoleon to take control of the Danish court. Lord Palmerston's speech was so successful that Perceval,

who formed his government in 1809, asked him to become Chancellor of

the Exchequer, then a less important office than it was to become from

the mid nineteenth century. Lord Palmerston preferred the office of

Secretary at War, charged exclusively with the financial business of

the army. Without a seat in the cabinet, he remained in the latter post

for 20 years. In the later years of Lord Liverpool's Tory administration, after the suicide of Castlereagh in 1822, the cabinet began to split along political lines. The more liberal wing of the Tory government made some ground, with George Canning becoming Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons, William Huskisson advocating

and applying the doctrines of free trade, and Catholic emancipation

emerging as an open question. Although Lord Palmerston was not in the

cabinet, he cordially supported the measures of Canning and his friends. Upon

the death of Lord Liverpool, Canning was called to be Prime Minister.

The more conservative Tories, including Peel, withdrew their support,

and an alliance was formed between the liberal members of the late

ministry and the Whigs. The post of Chancellor of the Exchequer was

offered to Lord Palmerston, who accepted it, but this appointment was

frustrated by some intrigue between the King and John Charles Herries.

Lord Palmerston remained Secretary at War, though he gained a seat in

the cabinet for the first time. The Canning administration ended after

only four months on the death of the Prime Minister, and was followed

by the ministry of Lord Goderich, which barely survived the year. The Canningites remained influential, and the Duke of Wellington hastened to include Lord Palmerston, Huskisson, Charles Grant, William Lamb, and The Earl of Dudley in

the government he subsequently formed. However, a dispute between

Wellington and Huskisson over the issue of parliamentary representation

for Manchester and Birmingham led to the resignation of Huskisson and

his allies, including Lord Palmerston. In the spring of 1828, after

more than twenty years continuously in office, Lord Palmerston found himself in opposition. Following

his move to opposition, Lord Palmerston appears to have focused closely

on foreign policy. He had already urged Wellington into active

interference in the Greek War of Independence, and he had made several visits to Paris, where he foresaw with great accuracy the impending overthrow of the Bourbons. On 1 June 1829 he made his first great speech on foreign affairs. Palmerston

was a great orator. His language was relatively unstudied and his

delivery somewhat embarrassed, but he generally found words to say the

right thing at the right time and to address the House of Commons in

the language best adapted to the capacity and the temper of his

audience. An attempt was made by the Duke of Wellington in September

1830 to induce Lord Palmerston to re-enter the cabinet, but he refused

to do so without Lord Lansdowne and Lord Grey, two notable Whigs. This can be said to be the point at which his party allegiance changed. When Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey,

came to power a few months later in 1830, he not surprisingly placed

foreign affairs in Lord Palmerston's hands. He entered the office with

great energy and continued to exert his influence there for twenty

years, which he held it from 1830-1834, 1835-1841, and 1846-1851. His

abrasive style earned him the nickname "Lord Pumice Stone", and his

manner of dealing with foreign governments who crossed him was the

original "gunboat diplomacy." The revolutions of 1830 gave a jolt to the settled European system that had been created after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The United Kingdom of the Netherlands was rent in half by the Belgian Revolution, the Kingdom of Portugal was the scene of civil war, and the Spanish were about to place an infant princess on the throne. Poland was in arms against the Russian Empire (the November Uprising),

while the northern powers formed a closer alliance that seemed to

threaten the peace and liberties of Europe. Lord Palmerston was

prepared to act with spirit and resolution in the face of these varied

difficulties, and the result was notable diplomatic success. William I of the Netherlands appealed

to the great powers that had placed him on the throne after the

Napoleonic Wars to maintain his rights; a conference assembled

accordingly in London.

The British solution involved the independence of Belgium, which Lord

Palmerston believed would greatly contribute to the security of

Britain, but any solution was not straightforward. On the one hand, the

northern powers were anxious to defend William I; on the other, many

Belgian revolutionaries, like Charles de Brouckère and Charles Rogier, supported the reunion of the Belgian provinces to France.

The policy of the UK government was a close alliance with France, but

one subject to the balance of power on the Continent, and in particular

the preservation of Belgium. If the northern powers supported William I

by force, they would encounter the resistance of France and the UK

united in arms. If France sought to annex Belgium, she would forfeit

the alliance of the UK, and find herself opposed by the whole of

Europe. In the end the UK's policy prevailed. Although the continent

had been close to war, peace was maintained on UK terms and Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, the widower of a British princess, was placed upon the throne of Belgium. In 1833 and 1834 the youthful Queens Maria II of Portugal and Isabella II of Spain were

the representatives and the hope of the constitutional parties of their

countries. Their positions were under some pressure from their

absolutist kinsmen, Dom Miguel of Portugal and Don Carlos of

Spain, who were the closest males in the lines of succession. Lord

Palmerston conceived and executed the plan of a quadruple alliance of

the constitutional states of the West to serve as a counterpoise to the

northern alliance. A treaty for the pacification of the Peninsula was

signed in London on 22 April 1834 and, although the struggle was

somewhat prolonged in Spain, it accomplished its objective. France had been a reluctant party to the treaty, and never executed her role in it with much zeal. Louis Philippe was accused of secretly favouring the Carlists -

the supporters of Don Carlos - and he rejected direct interference in

Spain. It is probable that the hesitation of the French court on this

question was one of the causes of the enduring personal hostility Lord

Palmerston showed towards the French King thereafter, though that

sentiment may well have arisen earlier. Although Lord Palmerston wrote

in June 1834 that Paris was "the pivot of my foreign policy", the

differences between the two countries grew into a constant but sterile

rivalry that brought benefit to neither.

Lord Palmerston was greatly interested by the diplomatic questions of Eastern Europe. During the Greek War of Independence he

had energetically supported the Greek cause and backed the Treaty of

Constantinople that gave Greece its independence. However, from 1830

the defence of the Ottoman Empire became

one of the cardinal objects of his policy. He believed in the

regeneration of Turkey. "All that we hear", he wrote to Bulwer (Lord

Dalling), "about the decay of the Turkish Empire, and its being a dead

body or a sapless trunk, and so forth, is pure unadulterated nonsense." His two great aims were to prevent Russia establishing itself on the Bosporus and to prevent France doing likewise on the Nile. He regarded the maintenance of the authority of the Sublime Porte as the chief barrier against both these developments. Lord

Palmerston had long maintained a suspicious and hostile attitude

towards Russia, whose autocratic government offended his liberal

principles and whose ever-growing size challenged the strength of the

British Empire. He was angered by the 1833 Treaty of Hünkâr İskelesi, a mutual assistance pact between Russia and the Ottomans, and he was a party to the mission of the Vixen to run the Russian blockade of Circassia in the late 1830s. In 1833 and 1835 his proposals to afford material aid to the Turks against Muhammad Ali, the pasha of Egypt,

was overruled by the cabinet. Lord Palmerston held that "if we can

procure for it ten years of peace under the joint protection of the

five Powers, and if those years are profitably employed in reorganizing

the internal system of the empire, there is no reason whatever why it

should not become again a respectable Power" and challenged the

[metaphor] that an old country, such as Turkey, should be in such

disrepair as would be warranted by the comparison: "Half the wrong

conclusions at which mankind arrive are reached by the abuse of

metaphors, and by mistaking general resemblance or imaginary similarity

for real identity." However,

when the power of Ali appeared to threaten the existence of the Ottoman

dynasty, particularly given the death of the Sultan on 1 July 1839, he

succeeded in bringing the great powers together to sign a collective

note on the 27 July pledging them to maintain the independence and

integrity of the Turkish Empire in order to preserve the security and

peace of Europe. However, by 1840 Ali had occupied Syria and won the Battle of Nezib against the Turkish forces. Lord Ponsonby, the British ambassador at Constantinople,

vehemently urged the British government to intervene. Having closer

ties to the pasha than most, France refused to be a party to coercive

measures against Ali despite having signed the note in the previous

year. Lord Palmerston, irritated at France's Egyptian policy, signed the London Convention of 15 July 1840 in London with Austria, Russia and Prussia -

without the knowledge of the French government. This measure was taken

with great hesitation, and strong opposition on the part of several

members of the UK cabinet. Lord Palmerston forced the measure through

in part by declaring in a letter to the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, that he would resign from the ministry if his policy were not adopted. The

London Convention granted Muhammad Ali hereditary rule in Egypt in

return for withdrawal from Syria and Lebanon, but was rejected by the

pasha. The European powers intervened with force, and the bombardment of Beirut, the fall of Acre,

and the total collapse of the power of Ali followed in rapid

succession. Lord Palmerston's policy was triumphant, and the author of

it had won a reputation as one of the most powerful statesmen of the

age. At the same time as she was acting with Russia in the Levant, the British government engaged in the affairs of Afghanistan in order to stem her advance into Central Asia, and fought the First Opium War with China which ended in the conquest of Chusan, later to be exchanged for the island of Hong Kong. In

all these actions Lord Palmerston brought to bear a great deal of

patriotic vigour and energy. This made him very popular among the

ordinary people of Britain, but his passion, propensity to act through

personal animosity, and imperious language made him seem dangerous and

destabilising in the eyes of the Queen and his more conservative colleagues in government. Within

a few months Melbourne's administration came to an end (1841) and Lord

Palmerston remained for five years out of office. The crisis was past,

but the change which took place by the substitution of François Guizot for Adolphe Thiers in France, and of Lord Aberdeen for

Lord Palmerston in the UK, was a fortunate event for the peace of the

world. Lord Palmerston had adopted the opinion that peace with France

was not to be relied on, and indeed that war between the two countries

was sooner or later inevitable. Aberdeen and Guizot inaugurated a

different policy; by mutual confidence and friendly offices, they

entirely succeeded in restoring the most cordial understanding between

the two governments, and the irritation which Lord Palmerston had

inflamed gradually subsided. During the administration of Sir Robert Peel, Lord Palmerston led a retired life, but he attacked with characteristic bitterness the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with the United States, which closed successfully some other questions he had long kept open. Lord

Palmerston's reputation as an interventionist and his unpopularity with

the Queen and other Whig grandees was such that when Lord John Russell attempted in December 1845 to form a ministry, the combination failed because Lord Grey refused

to join a government in which Lord Palmerston should resume the

direction of foreign affairs. A few months later, however, this

difficulty was surmounted; the Whigs returned to power, and Lord

Palmerston to the foreign office (July 1846) with a strong assurance

that Russell should exercise a strict control over his proceedings. A

few days sufficed to show how vain were this expectation.

The

French government regarded the appointment of Lord Palmerston as a

certain sign of renewed hostilities. They availed themselves of a

dispatch in which he had put forward the name of a Coburg prince as a

candidate for the hand of the young queen of Spain as a justification

for a departure from the engagements entered into between Guizot and

Lord Aberdeen. However little the conduct of the French government in

this transaction of the Spanish marriages can be vindicated, it is

certain that it originated in the belief that in Lord Palmerston France

had a restless and subtle enemy. The efforts of the British minister to

defeat the French marriages of the Spanish princesses, by an appeal to

the Treaty of Utrecht and

the other powers of Europe, were wholly unsuccessful; France won the

game, though with no small loss of honourable reputation.

The

revolutions of 1848 spread like a conflagration through Europe, and

shook every throne on the Continent except those of Russia, Spain, and

Belgium. Lord Palmerston sympathized, or was supposed to sympathize,

openly with the revolutionary party abroad. In particular, he was a

strong advocate of national self-determination, and stood firmly on the side of constitutional liberties on the Continent.

No state was regarded by him with more aversion than Austria. Yet, his opposition to Austria was chiefly based upon her occupation of northeastern Italy and

her Italian policy. Lord Palmerston maintained that the existence of

Austria as a great power north of the Alps was an essential element in

the system of Europe. Antipathies and sympathies had a large share in

the political views of Lord Palmerston, and his sympathies had ever

been passionately awakened by the cause of Italian independence. He

supported the Sicilians against the King of Naples, and even allowed arms to be sent them from the arsenal at Woolwich. Although he had endeavoured to restrain the King of Sardinia from

his rash attack on the superior forces of Austria, he obtained for him

a reduction of the penalty of defeat. Austria, weakened by the

revolution, sent an envoy to London to request the mediation of the UK,

based on a large cession of Italian territory. Lord Palmerston rejected

the terms he might have obtained for Piedmont. After a couple of years

this wave of revolution was replaced by a wave of reaction.

In Hungary the civil war, which had thundered at the gates of Vienna, was brought to a close by Russian intervention. Prince Schwarzenberg assumed

the government of the empire with dictatorial power. In spite of what

Lord Palmerston termed his judicious bottle-holding, the movement he

had encouraged and applauded, but to which he could give no material

aid, was everywhere subdued. The British government, or at least Lord

Palmerston as its representative, was regarded with suspicion and

resentment by every power in Europe, except the French republic. Even

that was shortly afterwards to be alienated by Lord Palmerston's attack

on Greece. When Louis Kossuth,

the Hungarian democrat and leader of its constitutionalists, landed in

the UK, Lord Palmerston proposed to receive him at Broadlands, a design

which was only prevented by a peremptory vote of the cabinet. This

state of things was regarded with the utmost annoyance by the British

court and by most of the British ministers. On many occasions, Lord

Palmerston had taken important steps without their knowledge, which

they disapproved. Over the Foreign Office he asserted and exercised an arbitrary dominion, which the feeble efforts of the premier could not control. The Queen and the Prince Consort did

not conceal their indignation at the fact that they were held

responsible for Lord Palmerston's actions by the other Courts of Europe. When Benjamin Disraeli and

others took several nights in the House of Commons to impeach Lord

Palmerston's foreign policy, the foreign minister responded to a

five-hour speech by Anstey with

a five-hour speech of his own, the first of two great speeches in which

he laid out a comprehensive defence of his foreign policy and of

liberal interventionism more generally. Reviewing his whole

parliamentary career - reminding him, he joked, of a drowning man's

visions of his past life - he said: I

hold that the real policy of England... is to be the champion of

justice and right, pursuing that course with moderation and prudence,

not becoming the Quixote of the world, but giving the weight of her

moral sanction and support wherever she thinks that justice is, and

whenever she thinks that wrong has been done. It

is generally supposed that Russell and the Queen both hoped that the

other would take the initiative and dismiss Lord Palmerston; the Queen

was dissuaded by Prince Albert, who took the limits of constitutional

power very seriously, and Russell by Lord Palmerston's prestige with

the people and his competence in an otherwise remarkably inept Cabinet. In 1850 he took advantage of Don Pacifico's

claims on the Hellenic government and blockaded the kingdom of Greece.

As Greece was under the joint protection of three powers, Russia and

France protested against its coercion by the British fleet. The French

ambassador temporarily left London, which promptly led to the

termination of the affair. Nevertheless, it was taken up in parliament

with great warmth. After a memorable debate (17 June), Lord Palmerston's policy was condemned by a vote of the House of Lords. The House of Commons was

moved by Roebuck to reverse the sentence, which it did 29 June by a

majority of 46, after having heard from Lord Palmerston. This was the

most eloquent and powerful speech he ever delivered, wherein he sought

to vindicate not only his claims on the Greek government for Don

Pacifico, but his entire administration of foreign affairs. It

was in this speech, which lasted five hours, Lord Palmerston made the

well known declaration that a British subject ought everywhere to be

protected by the strong arm of the British government against injustice

and wrong; comparing the reach of the British Empire to that of the

Roman Empire, in which a Roman citizen could walk the earth unmolested

by any foreign power. This was the famous Civis Romanus sum speech. Yet,

notwithstanding this parliamentary triumph, there were not a few of his

own colleagues and supporters who condemned the spirit in which the

foreign relations of the Crown were carried on. In that same year, the

Queen addressed a minute to the Prime Minister in which she recorded

her dissatisfaction at the manner in which Lord Palmerston evaded the

obligation to submit his measures for the royal sanction as failing in

sincerity to the Crown. This minute was communicated to Lord

Palmerston, who did not resign upon it; a crucial precedent, this was

taken to be an indication that he viewed the source of his power as no

longer being royal approval, but constitutional power. These

various circumstances, and many more, had given rise to distrust and

uneasiness in the cabinet, and these feelings reached their climax when

Lord Palmerston on the occurrence of the coup d'état by

which Louis Napoleon, President since 1848, made himself master of

France, expressed to the French ambassador in London, without the

concurrence of his colleagues, his personal approval of that act. Upon

this Lord John Russell advised his dismissal from office (Dec. 1851).

Lord Palmerston got his revenge a few weeks later, when he brought down

the Russell government in an amendment to the Militia Bill - his "tit

for tat with Johnny Russell" as he put it.

After a brief period of Tory minority government, the Earl of Aberdeen became Prime Minister in a coalition government of Whigs and Peelites (with Russell taking the role of Foreign Secretary and Leader of the House of Commons). Being impossible for them to form a government without Lord Palmerston, he was made Home Secretary in

December 1852. Many people considered this a curious appointment

because Lord Palmerston's expertise was so obviously in foreign affairs. Lord

Palmerston's exile from his traditional realm of the Foreign Office

meant he did not have full control over British policy during the

events precipitating the Crimean War. One of his biographers, Jasper Ridley, argues that had he been in control of foreign policy at this time, war in the Crimea would have been avoided. Lord

Palmerston argued in Cabinet, after Russian troops concentrated on the

Ottoman border in February 1853, that the Royal Navy should join the

French fleet in the Dardanelles as a warning to Russia. He was overruled, however. In May 1853 the Russians threatened to invade the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia unless

the Ottoman Sultan surrendered to their demands. Lord Palmerston argued

for immediate decisive action; the Royal Navy should be sent to the

Dardanelles to assist the Turkish navy and that Britain should inform

Russia of her intention to go to war with her if she invaded the

principalities. However, Lord Aberdeen objected to all of Lord

Palmerston's proposals. After prolonged arguments, Lord Aberdeen agreed

to send a fleet to the Dardanelles but objected to his other proposals.

The Russian Tsar was annoyed by Britain's actions but it was not enough

to deter him. When the British fleet arrived at the Dardanelles the

weather was rough so the fleet took refuge in the outer waters of the

straits. The Russians argued that this was a violation of the Straits Convention of

1841 and therefore invaded the two principalities. Lord Palmerston

thought that this was the result of British weakness and thought that

if Russia had been told that if they invaded the principalities the

British and French fleets would enter the Bosphorus or the Black Sea, she would have been deterred. In

Cabinet, Lord Palmerston argued for a vigorous prosecution of the war

against Russia by Britain but Lord Aberdeen objected, as he wanted

peace. Public opinion was on the side of the Turks and with Aberdeen

becoming steadily unpopular, Lord Dudley Stuart in

February 1854 noted, "Wherever I go, I have heard but one opinion on

the subject, and that one opinion has been pronounced in a single word,

or in a single name - Palmerston." As Home Secretary, Lord Palmerston strongly opposed Lord John Russell's

plans for giving the vote to sections of the urban working classes.

When the Cabinet agreed in December 1853 to introduce a bill during the

next session of Parliament in the form which Russell wanted, Lord

Palmerston resigned. However, Aberdeen told him that no definite

decision on reform had been taken and persuaded Lord Palmerston to

return to the Cabinet. On

28 March 1854 Aberdeen, along with France, declared war on Russia for

refusing to withdraw from the principalities. In the winter of 1854-5,

the British troops at Sevastopol suffered from the harsh conditions and military setbacks such as the Charge of the Light Brigade.

An angry mood swept the country and in January 1855 Aberdeen's

government was forced to set up a Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry

into the conduct of the war after losing a Commons vote on the matter.

After the vote, the government resigned. Queen Victoria did not want to

ask Lord Palmerston to form a government and so asked Lord Derby to

accept the premiership. Derby offered Lord Palmerston the office of

Secretary of State for War which he accepted under the condition that Clarendon remained

as Foreign Secretary. Clarendon refused and so Lord Palmerston refused

Derby's offer and Derby subsequently gave up trying to form a

government. The Queen sent for Lansdowne but

he was too old to accept so she asked Russell but none of his former

colleagues except Lord Palmerston wanted to serve under him. Having

exhausted the possible alternatives, the Queen invited Lord Palmerston

to Buckingham Palace on 4 February 1855 to form a government.

In March 1855 the old Tsar, Nicholas I, died and was succeeded by his son, Alexander II, who wished to make peace. However, Lord Palmerston found the peace terms too soft on Russia and so persuaded Napoleon III of France to

break off the peace negotiations. Lord Palmerston was confident that

Sevastopol could be captured and so put Britain in a stronger

negotiating position. In September Sevastopol surrendered when the French captured the Malakov whilst the British were driven back from the Redan after

many casualties. On 27 February 1856 an armistice was signed and after

a month's negotiations an agreement was signed at the Congress of Paris.

Lord Palmerston's demand for a demilitarized Black Sea was secured,

although his wish for the Crimea to be returned to the Ottomans was

not. The peace treaty was signed on 30 March 1856. In April 1856 Lord Palmerston was awarded the Order of the Garter by Victoria. In October 1856 the Chinese seized the pirate ship Arrow.

It had been registered as a British ship two years previously but was

owned by a notorious Chinese pirate. The titular captain was British,

and the crew was Chinese. It was intercepted in Chinese territorial

waters by Chinese coast guards and the Union Flag was pulled down. The

Chinese crew was arrested and the British captain was released. The

British Consul at Canton, Harry Parkes, protested against this insult to the flag and demanded an apology. The Chinese Commissioner Ye Mingchen refused and it was discovered that the Arrow's

registration as a British vessel expired three weeks before it was

seized and therefore had no right to fly the flag or to be exempt from

interception under international law. However, in disregard of

international conventions, Parkes refused to back down in order to save

face and protested that the Chinese did not know it was not a British

ship at the time they accosted it. Parkes sent the Royal Navy to

bombard Ye's palace and it was duly destroyed, along with a large part

of the city and a large loss of life. Ye retaliated by issuing a

proclamation calling on the people of Canton to "unite in exterminating

these troublesome English villains" and offering a $100 bounty for the

head of any Englishman as the British factories outside the city were

burned to the ground in reprisal. When

news of this reached the UK Cabinet, many Ministers thought that

Parkes' action had been both legally and morally wrong, and the

Attorney-General had no doubt that Parkes had acted in breach of

international law. Lord Palmerston, however, backed Parkes on the

principle that subordinates' actions should not be second-guessed. The

government's policy was subsequently strongly attacked in the Commons

on high moral grounds by Cobden and Gladstone during a censure debate.

On the fourth night of the debate (3 March 1857), Lord Palmerston

attacked Cobden and his speech as being pervaded by "an anti-English

feeling, an abnegation of all those ties which bind men to their

country and to their fellow-countrymen, which I should hardly have

expected from the lips of any member of this House. Everything that was

English was wrong, and everything that was hostile to England was

right." Lord

Palmerston went on to claim that if the motion of censure was carried

it would signal that the House had voted to "abandon a large community

of British subjects at the extreme end of the globe to a set of

barbarians - a set of kidnapping, murdering, poisoning barbarians." The

censure motion was carried by a majority of sixteen and Lord Palmerston

requested to the Queen that Parliament be dissolved for a general

election, which it duly was. On the international front, the

Sino-British crisis escalated subsequently and culminated in the Second Opium War. Lord Palmerston's stance was very popular in the country and his party achieved the biggest parliamentary majority since 1835. Cobden and Bright lost their seats and Lord Shaftesbury wrote of the election: [Palmerston]'s

popularity is wonderful — strange to say, the whole turns on his name.

There seems to be no measure, no principle, no cry, to influence men's

minds and determine elections; it is simply, "Were you, or were you

not? are you, or are you not, for Palmerston?" After the election, Lord Palmerston passed the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 which

for the first time made it possible for courts to grant a divorce and

removed divorce from the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts. The

opponents in Parliament, which included Gladstone, were the first in

British history to try and kill a bill by talking it out. Nonetheless, Palmerston was determined to get the bill through, which he did. In June news came to Britain of the Indian Mutiny and the attacks on British people there. Lord Palmerston sent Sir Colin Campbell and reinforcements to India. Lord Palmerston also agreed to transfer the authority of the British East India Company to the Crown. This was enacted in the Government of India Act 1858. After an Italian republican named Felice Orsini tried

to assassinate the French emperor with a bomb made in Britain, the

French were outraged. Lord Palmerston introduced a Conspiracy to Murder

Bill which made it a felony to

plot in Britain to murder someone abroad. At first reading, the

Conservatives voted for it but at second reading they voted against it.

Lord Palmerston lost by nineteen votes. Therefore, in February 1858 he

was forced to resign. However, the Conservatives lacked a majority and

Russell introduced a resolution in March 1859 arguing for widening the

franchise, which the Conservatives opposed but which was carried.

Parliament was dissolved and a general election ensued.

Lord Palmerston rejected an offer from Disraeli to become Conservative

leader, but he attended the meeting of 6 June 1859 in Willis's Rooms at

St James Street where the Liberal Party was formed. The queen asked Lord Granville to

form a government but although Palmerston agreed, Russell did not.

Therefore, on 12 June the Queen asked Lord Palmerston to become Prime

Minister. Russell and Gladstone agreed to serve under him. French intervention in Italy had created an invasion scare and Lord Palmerston established a Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom which reported in 1860. It recommended a huge programme of fortifications to protect the Royal Navy Dockyards, which Palmerston vigorously supported. Objecting to the enormous expense, William Gladstone threatened to resign as Chancellor when the proposals were accepted. The resulting forts came to be known as "Palmerston's Follies". Lord Palmerston's sympathies in the American Civil War (1861-5) were with the secessionist Southern Confederacy of

pro-slavery states. Although a professed opponent of the slave trade

and slavery, he also had a deep life-long hostility towards the United

States and believed that a dissolution of the Union would weaken the

United States (and therefore enhance British power) and that a southern

Confederacy "would afford a valuable and extensive market for British

manufactures". At the beginning of the Civil War, Britain had issued a proclamation of neutrality on 13 May 1861. Lord Palmerston decided to recognise the Confederacy as a belligerent and

to receive their unofficial representatives (although he decided

against recognising the South as a sovereign state because he thought

this would be premature). The United States Secretary of State, William Seward,

threatened to treat any country which recognised the Southern

separatists as a belligerent, as an enemy of the Union and the North.

Lord Palmerston ordered that reinforcements be sent to Canada because

he was convinced that the North would make peace with the South and

then invade Canada. When news reached him of the Confederate victory at Bull Run in

July 1861 he was very pleased, although 15 months later he wrote that

"the American [Civil] War... has manifestly ceased to have any

attainable object as far as the Northerns are concerned, except to get

rid of some more thousand troublesome Irish and Germans. It must be

owned, however, that the Anglo-Saxon race on both sides have shown

courage and endurance highly honourable to their stock". When news came of the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Antietam a week later, this made Palmerston reject Napoleon III of France's offer to recognise the Confederacy. Palmerston

continued to reject subsequent attempts by Confederate supporters to

persuade him to recognise the South as he thought the military

situation did not warrant it. The tide eventually turned in the United

States' favour when the Confederacy was defeated in 1865. After the seizure of the British ship Trent by a United States Navy vessel under Captain Charles Wilkes in

November 1861 to prevent two Southern separatist diplomats making their

way to Europe to campaign for support for the Confederacy against the

United States, Lord Palmerston ordered the Secretary of State for War

to send an extra 3,000 troops to Canada and demanded the release of the

two diplomats. Lord Palmerston called Wilke's actions "a declared and

gross insult" and in a letter to Queen Victoria on 5 December 1861 he

said, "Great Britain is in a better state than at any former time to

inflict a severe blow upon and to read a lesson to the United States

which will not soon be forgotten." In another letter to his Foreign Secretary the next day, he expected there was going to be war between Britain and the North: It

is difficult not to come to the conclusion that the rabid hatred of

England which animates the exiled Irishmen who direct almost all the

Northern newspapers, will so excite the masses as to make it impossible

for Lincoln and Seward to grant our demands; and we must therefore look

forward to war as the probable result. However,

the United States of America's government decided to hand back the

prisoners. Lord Palmerston was convinced that the reinforcements he had

sent to Canada had persuaded the North to acquiesce. Lord Palmerston received a law officer's report he had commissioned on 29 July 1862 which advised him to detain the CSS Alabama because it was being built for the South in the port of Birkenhead and it was therefore a breach of Britain's neutrality. Further, the cotton famine in

industrial regions of the North was beginning to bite, just at the time

when British popular opinion was starting to harden against the

Confederates. The ship had left the port after the order had been sent

on the 31 July but departed too soon for it to be detained, and it went

on to damage Northern shipping. The United States government accused

the British government of complicity in the construction of the ship

and, in the so-called Alabama claims, demanded damages from

Britain. Lord Palmerston refused to pay damages or to refer the dispute

to arbitration. It was not until after his death that his successor

(Gladstone) agreed to these demands and paid the United States

$15,500,000 in gold as damages. Lord Palmerston won another general election in July 1865, increasing his majority. He then had to deal with the outbreak of Fenian violence in Ireland. Lord Palmerston ordered the Viceroy of Ireland, Lord Wodehouse,

to take drastic measures, including a possible suspension of

trial-by-jury and a monitoring of Americans travelling to Ireland. He

believed that the Fenian agitation was caused by America. On 27

September 1865 he wrote to the Secretary for War: The

American assault on Ireland under the name of Fenianism may be now held

to have failed, but the snake is only scotched and not killed. It is

far from impossible that the American conspirators may try and obtain

in our North American provinces compensation for their defeat in

Ireland. He

advised that more armaments be sent to Canada and more troops sent to

Ireland. During these last few weeks of his life, Lord Palmerston

pondered on developments in foreign affairs. He began thinking of a new

friendship with France as "a sort of preliminary defensive alliance"

against America and looked forward to Prussia becoming more powerful as

this would balance against the growing threat from Russia. In a letter

to Russell he warned him that Russia "will in due time become a power

almost as great as the old Roman Empire... Germany ought to be strong

in order to resist Russian aggression." In

early October Lord Palmerston caught a chill and a violent fever. His

last words were, "That's Article 98; now go on to the next." (He was

thinking about diplomatic treaties.) Another

apocryphal version of his last words is: "Die, my dear doctor. That is

the last thing I shall do". He died at 10:45 am on Wednesday, 18

October 1865 two days before his eighty-first birthday. Although Lord

Palmerston wanted to be buried at Romsey Abbey, the Cabinet insisted that he should have a state funeral and be buried at Westminster Abbey, which he was, on 27 October 1865. He was the fourth person not royalty to be granted a state funeral (after Sir Isaac Newton, Lord Nelson, and the Duke of Wellington). Lord Palmerston was an Irish peer and so was not debarred from election to the British House of Commons. He was regarded as a nationalist and as a social conservative. He was considered by some of his contemporaries to be a womaniser; The Times named

him Lord Cupid (on account of his youthful looks), and he was cited, at

the age of 79, as co-respondent in an 1863 divorce case, although it

emerged that the case was nothing more than an attempted blackmail. In

1839, following the death of her husband, he married his mistress of

many years, Emily, Lady Cowper (née Lamb), a noted Whig hostess and sister of Lord Melbourne. They had no legitimate children, although at least one of Lord Cowper's putative children, Lady Emily Cowper, later Countess of Shaftesbury, was widely believed to have been Palmerston's. He was also an avowed abolitionist whose

attempts to abolish the slave trade was one of the most consistent

elements of his foreign policy. His opposition to the slave trade

created tensions with Southern American and the United States over his

insistence that the British navy had the right to search the vessels of

any country if they suspected the vessels were being used in the slave

trade. Lord

Palmerston is remembered for his light-hearted approach to government.

He is once said to have claimed of a particularly intractable problem

relating to Schleswig-Holstein, that only three people had ever understood the problem: one was Prince Albert, who was dead; the second was a German professor, who had gone insane; and the third was himself, who had forgotten it. Florence Nightingale said

of him after his death, "Tho' he made a joke when asked to do the right

thing, he always did it...He was so much more in earnest than he

appeared, he did not do himself justice." An early "biographer" of Palmerston was Karl Marx in 1853.