<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Sir Alfred Jules Ayer, 1910

- Painter Andrei Petrovich Ryabushkin, 1861

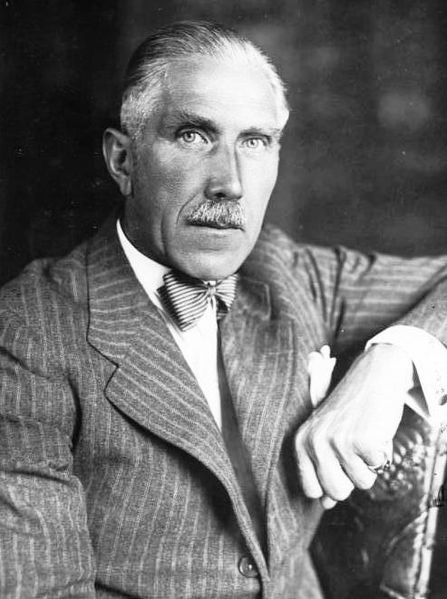

- Chancellor of Germany Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen zu Köningen, 1879

PAGE SPONSOR

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen zu Köningen (29 October 1879 – 2 May 1969) was a German nobleman, Roman Catholic monarchist politician, General Staff officer, and diplomat, who served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and as Vice-Chancellor under Adolf Hitler in 1933–1934. A member of the Catholic Centre Party until 1932, he was one of the most influential members of the Camarilla of President Paul von Hindenburg in the late Weimar Republic. It was largely Papen, who believed that Hitler could be controlled once he was in the government, who persuaded Hindenburg to put aside his scruples and approve Hitler as Chancellor in a cabinet not under Nazi Party domination. However, Papen and his allies were quickly marginalized by Hitler and he left the government after the Night of the Long Knives, during which some of his confidants were purged by the Nazis.

Born to a wealthy and noble Roman Catholic family in Werl, Province of Westphalia, son of Friedrich von Papen zu Köningen (1839 – 1906) and wife Anna Laura von Steffens (1852 – 1939), Papen was educated as an officer, including a period as a military attendant in the Kaiser's Palace, before joining the German General Staff in March 1913. He entered diplomatic service in December 1913 as a military attaché to the German ambassador in the United States. He travelled to Mexico (to which he was also accredited) in early 1914 and observed the Mexican Revolution, returning to Washington, D.C. on the outbreak of World War I in August 1914. He married Martha von Boch-Galhau (1880 – 1961) on 3 May 1905.

Papen was expelled from the United States during World War I for complicity in the planning of sabotage such as blowing up U.S. railroad lines. On 28 December 1915, he was declared persona non grata by the U.S. after his exposure and recalled to Germany. En route, his luggage was confiscated, and 126 check stubs were found showing payments to his agents. Papen went on to report on American attitudes, to both General Erich von Falkenhayn and William II, German Emperor. In April 1916, a United States federal grand jury issued an indictment against Papen for a plot to blow up Canada's Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario to Lake Erie, but Papen was then safely on German soil; he remained under indictment until he became Chancellor of Germany, at which time the charges were dropped. Later in World War I, Papen served as an officer first on the Western Front and then from 1917 as an officer on the General Staff in the Middle East and as a major in the Ottoman army in Palestine.

Papen also served as intermediary between the Irish Volunteers and the German government regarding the purchase and delivery of arms to be used against the British during the Easter Rising of 1916, as well as serving as an intermediary with the Indian nationalists in the Hindu German Conspiracy. After achieving the rank of lieutenant-colonel, he returned to Germany and left the army in 1918. He entered politics and joined the Catholic Centre Party (Zentrum), in which the monarchist Papen formed part of the conservative wing. He was a member of the parliament of Prussia from 1921 to 1932. In the 1925 presidential elections, he surprised his party by supporting the right-wing candidate Paul von Hindenburg over the Centre Party's Wilhelm Marx. He was a member of the "Deutscher Herrenklub" (German Gentlemen's Club) of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. On 1 June 1932 he moved from relative obscurity to supreme importance when President Paul von Hindenburg appointed him Chancellor, even though this meant replacing his own party's Heinrich Brüning. The day before, he had promised party chairman Ludwig Kaas not to accept any appointment, and Kaas accordingly branded him the "Ephialtes of the Centre Party"; Papen forestalled being expelled by leaving the party on 3 June 1932. The French ambassador in Berlin, André François-Poncet,

wrote at the time that Papen's selection by Hindenburg as chancellor

"met with incredulity." Papen, the ambassador continued, "enjoyed the

peculiarity of being taken seriously by neither his friends nor his

enemies. He was reputed to be superficial, blundering, untrue,

ambitious, vain, crafty and an intriguer." The cabinet which Papen formed, with the assistance of General Kurt von Schleicher, was known as the "cabinet of barons" or as the "cabinet of monocles" and was widely regarded with ridicule by Germans. Except from the conservative German National People's Party (DNVP), Papen had practically no support in the Reichstag. Papen ruled in an authoritarian manner by launching a coup against the center-left coaltion government of Prussia (the so-called Preußenschlag) and repealing his predecessor's ban on the SA as a way to appease the Nazis, whom he hoped to lure into supporting his government. Soon afterward, Papen called an election for July 1932 in

hopes of getting a majority in the Reichstag. However, he didn't even

come close — in fact, the Nazis gained 123 seats to become the largest

party. When this Reichstag first assembled, Papen obtained in advance

from Hindenburg a decree to dissolve it. He initially didn't bring it

along, having received a promise that there'd be an immediate objection

to an expected Communist motion

of censure. However, when no one objected, Papen ordered one of his

messengers to get the order. When he demanded the floor in order to

read it, newly elected Reichstag president Göring pretended not to see him; his Nazis had decided to support the Communist motion.

The censure vote passed overwhelmingly, forcing another election. In the November 1932 election the

Nazis lost seats, but Papen was still unable to get a majority. Papen

then decided to try to negotiate with Hitler, but Hitler's reply

contained so many conditions that Papen gave up all hope of reaching

agreement. Soon afterward, under pressure from Schleicher, Papen

resigned on November 17. Papen

held out hope of being reappointed by Hindenburg, fully expecting that

the aging President would find Hitler's demands unacceptable. Indeed,

when Schleicher suggested on 1 December that he might be able to get

support from the Nazis, Hindenburg blanched and told Papen to try to

form another government. However, at a cabinet meeting the next day,

Papen was informed that there was no way to maintain order against the

Nazis and Communists. Realizing that Schleicher was deliberately trying

to undercut him, Papen asked Hindenburg to fire Schleicher as defence

minister. Instead, Hindenburg told Papen that he was appointing

Schleicher as chancellor. Schleicher hoped to establish a broad

coalition government by gaining the support of both Nazi and Social

Democratic trade unionists. As

it became increasingly obvious that Schleicher would be unsuccessful in

his maneuvering to maintain his chancellorship under a parliamentary

majority, Papen worked to undermine Schleicher. Along with DNVP leader Alfred Hugenberg, Papen formed an agreement with Hitler under which the Nazi leader would become Chancellor of a coalition government with the Nationalists, and with Papen serving as Vice Chancellor of the Reich and prime minister of Prussia. On

23 January 1933 Schleicher admitted to President Hindenburg that he had

been unable to obtain a majority of the Reichstag, and asked the

president to declare a state of emergency. By this time, the elderly

Hindenburg had become irritated by the Schleicher cabinet's policies

affecting wealthy landowners and industrialists. Simultaneously,

Papen had been working behind the scenes and used his personal

friendship with Hindenburg to assure the President that he, Papen,

could control Hitler and could thus finally form a government based on

the support of the majority of the Reichstag. Hindenburg

refused to grant Schleicher the emergency powers he sought, and

Schleicher resigned on 28 January. Though Papen flirted with leaving

Hitler out of the cabinet and becoming chancellor himself, in the end

the President, who had previously vowed never to allow Hitler to become

chancellor, appointed Hitler to the post on 30 January 1933, with von

Papen as Vice-Chancellor. The remaining members of the cabinet were

conservatives, with the exception of two Nazis. At

the formation of Hitler's cabinet on 30 January, the Nazis had three

cabinet posts (including Hitler) to the conservatives' eight.

Additionally, as part of the deal that allowed Hitler to become

chancellor, Papen was granted the right to sit in on every meeting

between Hitler and Hindenburg. Counting on their majority in the

Cabinet and on the closeness between himself and Hindenburg, Papen had

anticipated "boxing Hitler in." Papen boasted to intimates that "Within

two months we will have pushed Hitler so far in the corner that he'll

squeak." To the warning that he was placing himself in Hitler's hands,

Papen replied "You are mistaken. We've hired him." However, Hitler and his allies instead quickly marginalized Papen and the rest of the cabinet. For example, Hermann Göring had

been appointed deputy interior minister of Prussia, but frequently

acted without consulting his nominal superior, Papen. Neither Papen nor

his conservative allies waged a fight against the Reichstag Fire Decree in late February or the Enabling Act in March. On 8 April Papen travelled to the Vatican to offer a Reichskonkordat that defined the German state's relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. During Papen's absence, the Nazified Landtag of Prussia elected Göring as prime minister on 10 April. Conscious

of his own increasing marginalization, Papen began covert talks with

other conservative forces with the aim of convincing Hindenburg to

dismiss Hitler. Of special importance in these talks was the growing

conflict between the German military and the paramilitary Sturmabteilung (SA), led by Ernst Röhm. In

early 1934 Röhm continued to demand that the storm troopers become

the core of a new German army. Many conservatives, including

Hindenburg, felt uneasy with the storm troopers' demands, their lack of

discipline and their revolutionary tendencies. With the Army command recently having hinted at the need for Hitler to control the SA, Papen delivered an address at the University of Marburg on 17 June 1934 where he called for the restoration of some freedoms, demanded an end to the calls for a "second revolution" and advocated the cessation of SA terror in the streets. In this "Marburg speech"

Papen said that "The government [must be] mindful of the old maxim

'only weaklings suffer no criticism'" and that "No organization, no

propaganda, however excellent, can alone maintain confidence in the

long run." The speech was crafted by Papen's speech writer, Edgar Julius Jung, with the assistance of Papen's secretary Herbert von Bose and Catholic leader Erich Klausener. The

vice chancellor's bold speech incensed Hitler, and its publication was

suppressed by the Propaganda Ministry. Angered by this reaction and

stating that he had spoken on behalf of Hindenburg, Papen told Hitler

that he was resigning and would inform Hindenburg at once. Hitler knew

that accepting the resignation of Hindenburg's long-time confidant,

especially during a time of tumult, would anger the ailing president.

He guessed right; not long afterward Hindenburg gave Hitler an

ultimatum — unless he acted to end the state of tension in Germany,

Hindenburg would throw him out of office and turn over control of the

government to the army. Two weeks after the Marburg speech,

Hitler responded to the armed forces' demands to suppress the ambitions

of Röhm and the SA by purging the SA leadership. The purge, known

as the Night of the Long Knives,

took place between 30 June and 2 July 1934. In the purge, Röhm and

much of the SA leadership were murdered. General von Schleicher, who as

Chancellor had been scheming with some of Hitler's rivals within the

party to separate them from their leader, was slain along with his wife. Though

Papen's bold speech against some of the excesses committed by Nazism

had angered Hitler, Hitler was aware that he could not act directly

against the vice chancellor without offending Hindenburg. But Papen's

office was ransacked by the SS, his associates von Bose and Klausener were

shot dead at their desks, and Jung was arrested and imprisoned in a

concentration camp where he was fatally shot a few days later. Several

of Papen's staff members were interned in concentration camps. Papen

himself was placed under house arrest at his villa with his telephone

line cut, though some accounts indicate that this "protective custody"

was ordered by Göring, who felt the ex-diplomat could be useful in

the future. The following day, Papen's resignation as vice chancellor

was accepted. Despite the events of the Night of the Long Knives, Papen accepted within a month the assignment from Hitler as German ambassador in Vienna, where Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss had

just been murdered in a failed Nazi coup. In Hitler's words, Papen's

duty was to restore "normal and friendly relations" between Germany and

Austria. Papen

also contributed to achieving Hitler's goal of undermining Austrian

sovereignty and bringing about the Nazis' long-dreamed-of Anschluss (unification with Germany). Winston Churchill reports in his book The Gathering Storm (1948)

that Hitler appointed Papen for "the undermining or winning over of

leading personalities in Austrian politics". Churchill also quotes the

U.S. minister in Vienna as saying of Papen "In the boldest and most

cynical manner...Papen proceeded to tell me that... he intended to use

his reputation as a good Catholic to gain influence with Austrians like Cardinal Innitzer." Ironically,

one of the plots called for Papen's murder by Austrian Nazi

sympathizers as a pretext for a retaliatory invasion by Germany. Though

Papen was dismissed from his mission in Austria on 4 February 1938,

Hitler drafted Papen to arrange a meeting between the German dictator

and Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg at Berchtesgaden. The

ultimatum that Hitler presented Schuschnigg, at the meeting on 12

February 1938, led to the Austrian government's capitulation to German

threats and pressure, and paved the way for the Anschluss, which was proclaimed on 13 March 1938. Papen later served the German government as Ambassador to Turkey from 1939 to 1944. There, he survived a Soviet assassination attempt on 24 February 1942 by agents from NKVD — a bomb prematurely exploded, killing the bomber and no one else, although Papen was slightly injured. However,

some Soviet sources say that the assassination attempt was in fact the

work of one of Nazi Germany's own secret services. Its goal was

apparently to disrupt Soviet-Turkish relations and even to push Turkey

into declaring war on the Soviet Union and joining Germany. The

assassination was not meant to be successful, although had Von Papen

been killed, it would not have been a great blow to Hitler as Papen was

known to be in semi-secret opposition to the Nazis. After Pope Pius XI died in 1939, his successor Pope Pius XII did not renew his honorary title of Papal Chamberlain, probably in the light of Papen's political role for the Hitler régime. As nuncio, the future Pope John XXIII, Angelo Roncalli, was acquainted with Papen in Greece and Turkey during World War II. During the war, the German government considered appointing Papen ambassador to the Holy See, but Pope Pius XII, after consulting Konrad von Preysing, Bishop of Berlin, rejected this proposal.

In

August 1944, Papen had his last meeting with Hitler after arriving back

in Germany from Turkey. Here, Hitler awarded Papen the Knight's Cross

of the Military Merit Order. Papen

was captured along with his son Franz Jr. by U.S. Army Lt. James E.

Watson and members of the 550th Airborne battalion near the end of the

war at his home. According to Watson as he was put into the jeep for

his ride into a POW camp,

he was heard to remark (in English), "I wish this terrible war were

over." At that one of his sergeants responded, "So do 11 million other

guys!" Papen was one of the defendants at the main Nuremberg War Crimes Trial.

The court acquitted him, stating that he had, in the court's view,

committed a number of "political immoralities," but that these actions

were not punishable under the "conspiracy to commit crimes against peace"

charged in Papen's indictment. He was later sentenced to eight years in

prison by a West German denazification court, but was released on

appeal in 1949. Papen tried unsuccessfully to re-start his political

career in the 1950s, and lived at the Castle of Benzenhofen in Upper Swabia. Pope John XXIII restored his title of Papal Chamberlain on 24 July 1959. Papen was also a Knight of Malta, and was awarded the Grand Cross of the Pontifical Order of Pius IX. Papen

published a number of books and memoirs, in which he defended his

policies and dealt with the years 1930 to 1933 as well as early western Cold War politics. Papen praised the Schuman Plan as "wise and statesmanlike" and believed in the economic and military unification and integration of Western Europe. Franz von Papen died in Obersasbach, West Germany, on 2 May 1969 at the age of 89.