<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Lev Semenovich Pontryagin, 1908

- Architect Louis Henri Sullivan, 1856

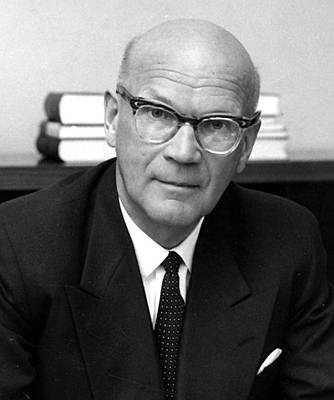

- 8th President of Finland Urho Kaleva Kekkonen, 1900

Urho Kaleva Kekkonen (3 September 1900 – 31 August 1986) was a Finnish politician who served as Prime Minister of Finland (1950–1953, 1954–1956) and later as the eighth President of Finland (1956–1982). Kekkonen continued the "active neutrality" policy of President Juho Kusti Paasikivi, which came to be known as the "Paasikivi-Kekkonen line". This policy allowed Finland to retain independence and trade with the nations of both NATO and the Warsaw Pact. Kekkonen was the longest-serving President of Finland.

Kekkonen was born in Pielavesi in the Savo region of Finland, the son of Juho Kekkonen and Emilia Pylvänäinen, but spent his childhood in Kainuu. His family were farmers (though not poor tenant farmers, as some of his supporters claimed). His father, originally a farm-hand and forestry worker, eventually became a forestry manager and stock agent at Halla Ltd. Kekkonen had some distant German ancestry. It was claimed that Kekkonen's family had lived in a poor farmhouse without a chimney; however, it was later found out that the photographic evidence to back up this claim was fake, and that the chimney had simply been retouched off the photographs depicting Kekkonen's childhood home. His school years did not go smoothly. During the Finnish Civil War, he fought for the White Guard and led a firing squad in Hamina. Kekkonen personally admitted to having killed a man in battle, but not to a mass execution of Red troops committed by his squad. However, a photograph taken at the time seems to prove that Kekkonen was there during the execution.

In independent Finland, Kekkonen first worked as a journalist in Kajaani. He moved to Helsinki in 1921 to study law, graduating as a Master of Laws in 1926. During his studies he worked as a policeman from

1921 to 1927. It was during this time that he met his future wife,

Sylvi Salome Uino (1900–1974), a typist at the police office. They had

two sons, Matti (born 1928) and Taneli (1928–1985). Matti Kekkonen

served as a Centre Party member of Parliament from 1958 to 1969. In 1927, Kekkonen became a lawyer and

worked for the Association of Rural Municipalities. However, he had to

resign in 1932 due to abrasive comments. Kekkonen became a Doctor of Laws in 1936. At Helsinki University he was active in the Northern Ostrobothnian student nation and was the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper Ylioppilaslehti 1927-1928. He was also an active athlete. His best achievement as a sportsman was to become Finnish high jump champion (1.85 m) in 1924. The standing jump was his best discipline. Politically, he was a nationalist and his ideological roots lay in the nationalistic student politics of the newly independent Finland and the radicalism of the right.

When the Academic Karelia Society (Akateeminen Karjala-Seura), an

organization which favoured Finland's annexation of East Karelia,

supported the far-right Mäntsälä revolt in 1932,

Kekkonen and over 100 other moderate members resigned from the

organization. According to Johannes Virolainen, a longtime Agrarian and

Centrist politician, some Finnish right-wingers started to hate and

mock Kekkonen already after this decision as a power-hungry opportunist. In 1933, Kekkonen joined the Agrarian League (later renamed the Centre Party). That year he also became a civil servant at the Ministry of Agriculture and made his first attempt to get elected to the Parliament. His second trial to get elected into the Parliament succeeded in 1936 and he became Justice Minister,

serving from 1936 to 1937, where he committed a procedure that was

known as the "Tricks of Kekkonen" (Kekkosen konstit) when he tried to

ban the right-wing extremist Patriotic People's Movement (Isänmaallinen Kansanliike, IKL). The procedure was not entirely legal and was halted by the Supreme Court. He was also Minister of Home Affairs from 1937 to 1939. He was not a member of the cabinets during the Winter War or the Continuation War. He opposed the Moscow peace treaty in the Parliament in March 1940 (being the sole member to vote against the treaty) and during the Continuation War, he served as the director of the Karelian Evacuees'

Welfare Centre from 1940 to 1943 and as the Ministry of Finance's

commissioner for coordination from 1943 to 1945, his task being to

rationalise public administration. By that time, he had become one of

the leading politicians within the so-called Peace opposition. In 1944, he again became Minister of Justice, serving until 1946, and had to deal with the war-responsibility trials. Kekkonen was a Deputy Speaker of the Parliament 1946–1947, and was the Speaker from 1948 to 1950. In

the 1950 Presidential election, Kekkonen was chosen as the candidate of

the Agrarian Party and conducted a vigorous campaign against the

incumbent President Juho Kusti Paasikivi. Kekkonen finished third in the first and only ballot, receiving 62 votes in the electoral college, while Paasikivi was reelected with 171. After the election Paasikivi appointed Kekkonen as Prime Minister. In all his five cabinets he emphasized his role to create and maintain friendly relations with the Soviet Union.

He was an authoritarian person and embarrassed his opponents in public.

He was ousted in 1953, although he returned as Prime Minister from 1954

to 1956. Kekkonen also served as Minister of Foreign Affairs for

periods in 1952–1953 and 1954 whilst he was Prime Minister. In the presidential election of 1956, Kekkonen defeated the Social Democrat Karl-August Fagerholm by

two votes in the electoral college (151-149) and was elected President.

The 1956 presidential campaign was notably vicious, with many personal

attacks against several major candidates, especially against Kekkonen.

A tabloid gossip newspaper, "The Sensation News" (Sensaatio-Uutiset),

accused Kekkonen of fistfighting, excessive drinking and extramarital

affairs. The drinking and womanizing charges were partly correct: at

times, in evening parties with his friends, Kekkonen got drunk, and he

had at least two longtime mistresses. As president, Kekkonen continued

the neutrality policy of President Paasikivi, which came to be known as the Paasikivi-Kekkonen line. From the beginning he ruled with the assumption that the Soviet Union accepted only him. Because of defectors like Oleg Gordievsky and

the opening of the Soviet archives it is known that keeping Kekkonen in

power was the main task of the Soviet Union in its relations with

Finland. During Kekkonen's term, the balance of power between the Finnish Council of State and

the President was heavily tilted towards the President. In principle

and formally, parliamentarism was followed; governments were nominated

by a parliamentary majority. However, the Kekkonen-era councils were

often in bitter internal disagreement and the alliances broke down

easily. New governments often tried to reverse their predecessors'

policies. Kekkonen

extensively used his power to nominate ministers and railroaded new

compositions of governments through the parliamentary process. He also

used (publicly and with impunity) the old boy network to

bypass the government and communicate directly with high officials.

Only after Kekkonen's term, governments began to remain stable

throughout the entire period between elections. It must be added,

however, that during Kekkonen's presidency, a few parties were in most

governments - mainly the Centrists, Social Democrats and Swedish

People's Party - while the People's Democrats and Communists were often

in government since 1966, and the Conservatives were in opposition for

at least 20 years. Kekkonen's policies, especially towards the USSR, were criticised within his own party by Veikko Vennamo,

who broke off his Centre Party affiliation when Urho Kekkonen was

elected president of Finland (1956). In 1959, Vennamo established his

populistic Agrarian Party (also translated as the Rural Party), forerunner of the populistic and nationalistic, Perus-suomalaiset Basic Finns. In

April 1961 Kekkonen was already planning to dissolve parliament in

order to influence the alliance behind his potential presidential rival Olavi Honka. In addition, the Soviet Union sent a diplomatic note in late October, citing an article of the FCMA treaty referring to the threat of war. Concerning this Note Crisis,

the most common view is that the Soviet Union was motivated by a desire

to ensure Kekkonen's re-election. After Honka dropped his candidacy,

Kekkonen was re-elected by an overwhelming vote of 199 out of 300

electoral college votes in the 1962 Presidential election. In addition

to his own party, Kekkonen had received the backing of the Swedish People's Party and the Finnish People's Party (a

small classical liberal party). Also the Conservatives (National

Coalition Party) quietly supported Kekkonen, although they had no

official presidential candidate after Honka's withdrawal. As a result

of the

note crisis, genuine opposition to Kekkonen disappeared, and he

acquired an exceptionally strong - later even autocratic - status as

the political leader of Finland. Throughout his time as president, Kekkonen did his best to keep political rivals in check. The Centre Party's rival, National Coalition Party was

kept in opposition despite good performance in elections. On a few

occasions, the parliament was dissolved as the political composition

did not please Kekkonen. Too prominent Centre Party members often found

themselves sidelined, as Kekkonen negotiated directly with the lower

lever. The so called "Mill Letters" of Kekkonen were a continuous

stream of directives to high officials, politicians, journalists etc.

Nevertheless, Kekkonen did not use coercive measures and some leading

politicians, most notably Tuure Junnila and Veikko Vennamo, "branded" themselves as anti-Kekkonen. In the 1960s Kekkonen was responsible for a number of foreign-policy initiatives, involving for example the Nordic nuclear-free zone, the border agreement with Norway and a Conference on Security and

Cooperation in Europe in 1969. The purpose of these initiatives was to

avoid the enforcement of the military articles in the FCMA treaty - in

other words, military cooperation between Finland and the Soviet Union

- and thus to strengthen Finland's attempt to practice a policy of

neutrality. Following the invasion of Czechoslovakia in

1968 pressure for neutrality increased. Kekkonen informed the Soviets

in 1970 that he would not continue as president, nor would the FCMA

treaty be extended, if the Soviet Union was no longer prepared to

recognize Finland's neutrality.

Kekkonen

was re-elected for a third term in 1968. In that year's election, he

received the support of five political parties - the Centre Party, the Social Democrats, the Social Democratic Union of Workers and Smallholders (a short-lived SDP fraction), the Finnish People's Democratic League (a communist front), and the Swedish People's Party. Kekkonen received 201 votes in the electoral college, with the National Coalition party's

candidate finishing in second place with 66 votes. Vennamo was the

third presidential candidate and got 33 votes. Although Kekkonen had

been re-elected with two-thirds of the vote, he was so displeased with

his opponents and their behaviour that he publicly refused to be a

presidential candidate again. Especially Vennamo infuriated Kekkonen

with his bold and constant criticism of the President and his foreign

policy. Kekkonen labelled Vennamo a "cheat" and "demagogue".

In

1973, he was re-elected by emergency law which saw his presidency

extended by four years. This was accomplished by implying that, if he

was not re-elected, the Soviets would not accept Finland's free trade

agreement with the EEC.

The tactic secured National Coalition's support and thus enabled the

enactment of an emergency law. The elimination of any significant

opposition and competition meant de facto political autocracy for

Kekkonen. The year 1975 can be regarded as marking the zenith of his

power, when he dissolved parliament and hosted the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) in Helsinki with the assistance of a caretaker government. In

the 1978 Presidential election, Kekkonen's candidacy was blindly

supported by nine political parties, including the Social Democratic,

Centre and National Coalition parties, effectively meaning that there

were no serious rivals left. Kekkonen humiliated his opponents by not

appearing in televised presidential debates. Kekkonen won 259 out of

the 300 electoral college votes, with his nearest rival, Raino

Westerholm of the Christian Union, receiving 25. Why

did Kekkonen cling to the Presidency until his rapidly worsening

illness, arteriosclerosis, forced him to resign in October 1981?

According to Finnish historians and political journalists, there were

at least three reasons for this: First, he did not believe that any of

his successor candidates would lead Finland's foreign policy toward the

Soviet Union well enough. Secondly, at least until the summer of 1978,

when he had to use all his diplomatic skills to reject the Soviet

Defence Minister Ustinov's offer of a closer military co-operation

between Finland and the Soviet Union without offending his guest, he

believed that the Finnish-Soviet relations could still be improved a

lot, and that he could help improve them with his experience. Thirdly,

he maintained that by working as long as he could, he would remain

healthy and alive as long as possible. Kekkonen's most severe critics, such as Veikko Vennamo,

claimed that he remained President so long mainly because he and his

closest associates were so power hungry. In 1979 Urho Kekkonen was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize. From December 1980, Kekkonen began to suffer from an undisclosed disease that seemed to affect his brain functions,

sometimes leading to delusional thoughts. In fact, he had begun to

suffer from occasional brief memory lapses in the autumn of 1972. These

memory lapses became more frequent in the late 1970s. Around the same

time, Kekkonen's eyesight deteriorated, so during his last few years in

office, he had to have all official papers typed in block letters.

Kekkonen also suffered from a declining sense of balance in his legs

since the mid-1970s, from enlargement of his prostate gland since 1974,

from occasionally violent headaches, and from diabetes since the autumn

of 1979. According to one of his biographers,

Juhani Suomi, Kekkonen did not give any thought about resigning until

his physical condition began to decline in July 1981. The 80-year-old

President then began to seriously consider resigning, most likely in

early 1982. Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto had

defeated Kekkonen in 1981. In April, Koivisto had done what none other

had dared during Kekkonen's presidency, namely stated that under the

Constitution, the Prime Minister and cabinet are responsible to the

Parliament and not to the President, and refused to resign at

Kekkonen's request. Historians and journalists debate the precise

meaning of this dispute. According to Seppo Zetterberg, Allan Tiitta

and Pekka Hyvärinen, for example, Kekkonen wanted to force

Koivisto to resign to decrease his chances of succeeding him as

President. According to Juhani Suomi, by contrast, the dispute was

about the scheming between prospective presidential candidates, such as

Koivisto. Kekkonen at times criticized Koivisto for making political

decisions too slowly and for pondering too much, especially for

speaking too unclearly and philosophically. This was

generally seen as the death knell of the Kekkonen era. Kekkonen took

ill in August during a fishing trip to Iceland.

He went on medical leave on 10 September, before finally resigning due

to ill health on 26 October 1981, aged 81. There is no report available

about his illness, as the papers have been moved to an unknown

location, but it is commonly said that he suffered from vascular dementia probably due to atherosclerosis. Kekkonen died at Tamminiemi in 1986, three days short of his 86th birthday, and was buried with full honors. His heirs restricted access to his diaries. An "authorized" biography was commissioned from Juhani Suomi, who subsequently defended the interpretation of history therein and denigrated most other interpretations. Some

of Kekkonen's actions are controversial in modern Finland. He often

pulled a "Moscow card" when his authority was threatened. Still he was

hardly the only Finnish politician with close relations to Soviet

representatives. The mildly authoritarian behavior of Kekkonen during

his presidential term is one of the main reasons for the reforms of the

Finnish Constitution in 1984–2003. In these reforms, the power of

Parliament and Prime Minister was increased at the expense of the

President. Several of these changes have been initiated by Kekkonen's

successors. Kekkonen was largely responsible for Finlandization,

the policy that allowed the Soviet Union to exert power over Finland.

The policy spanned his whole presidency and human rights violations

associated with Finlandization were carried out under orders from

Kekkonen. He

for example insisted that all Soviet defectors, who managed to escape

across the border to Finland, should be forcibly returned to the Soviet

Union.