<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri, 1667

- Poet Robert Fergusson, 1750

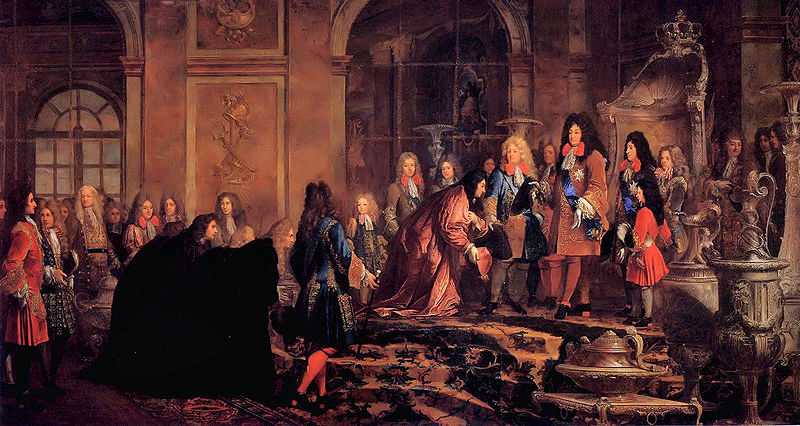

- King of France and of Navarre Louis XIV, 1638

Louis XIV (5 September 1638 – 1 September 1715), known as the Sun King (French: le Roi Soleil), was King of France and of Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days, and is the longest documented reign of any European monarch.

Louis began personally governing France in 1661 after the death of his prime minister, the Italian Cardinal Mazarin. An adherent of the theory of the divine right of kings, which advocates the divine origin and lack of temporal restraint of monarchical rule, Louis continued his predecessors' work of creating a centralized state governed from the capital. He sought to eliminate the remnants of feudalism persisting in parts of France and, by compelling the noble elite to inhabit his lavish Palace of Versailles, succeeded in pacifying the aristocracy, many members of which had participated in the Fronde rebellion during Louis' minority.

For much of Louis's reign, France stood as the leading European power, engaging in three major wars — the Franco-Dutch War, the War of the League of Augsburg, and the War of the Spanish Succession — and two minor conflicts — the War of Devolution and the War of the Reunions. He encouraged and benefited from the work of prominent political, military and cultural figures such as Mazarin, Colbert, Turenne and Vauban, as well as Molière, Racine, Boileau, La Fontaine, Lully, Le Brun, Rigaud, Le Vau, Mansart, Perrault and Le Nôtre.

Upon his death just days before his seventy-seventh birthday, Louis was succeeded by his five-year-old great-grandson who became Louis XV. All his intermediate heirs — his son Louis, le Grand Dauphin; the Dauphin's eldest son Louis, duc de Bourgogne; and Bourgogne's eldest son Louis, duc de Bretagne — predeceased Louis. Louis XIV was born on 5 September 1638 in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye to Louis XIII and Anne of Austria.

His birth came after twenty-three years of his estranged parents'

childlessness, leading contemporaries to regard him as a divine gift,

and his birth, a miracle. Thus, he was named "Louis-Dieudonné"

(Louis-God-given); also he bore the traditional title of French heirs apparent — Dauphin. Louis was a product of noteworthy European ruling houses. His paternal grandparents were Henri IV and Marie de' Medici; and both his maternal grandparents were Habsburgs — Philip III of Spain and Margaret of Austria. Through them, Louis was descended from various historical figures, such as Holy Roman Emperors — Charles V and Frederick Barbarossa. Other ancestors included the first monarchs of a united Spain — Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon — and the founder of Russia's first dynasty — Rurik the Viking. Louis was also a descendant of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy and the poet, Charles d'Orléans, as well as the last of the great Condottieri — Giovanni de' Medici. Most importantly for his and his descendant's rights to the throne, Louis was descended in the direct legitimate male line from Saint Louis, and through him, from Hugh Capet,

the first King of France. Tracing Louis's ancestry to the tenth

generation, genealogist C. Carretier calculated his ancestry to be

approximately 28% French, 26% Spanish, 11% Austro-German and 10%

Portuguese, the rest being Italian, Slavic, English, Savoy ard and

Lorrainer. Although

Anne produced the heir, Louis, and his brother, Philippe, Louis XIII

doubted her political abilities. He thus decreed that a regency council

should rule on Louis' behalf in the event of a minority. He nonetheless did name her the head of the council. On 14 May 1643, upon Louis XIII's death and his young son's accession to the throne, Anne had his will annulled by the Parlement de Paris (a judicial body comprising mostly nobles and high clergymen), abolished the regency council and became sole regent. She then entrusted power to Cardinal Mazarin. Subsequently, in 1648, Mazarin successfully negotiated the Peace of Westphalia. Although war continued between France and Spain until the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659, the Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years' War in Germany. Its terms ensured Dutch independence from Spain, awarded some autonomy to the various German princes, and granted Sweden seats on the Reichstag and territories to control the mouths of the Oder, Elbe and Weser. However, it profited France the most. Austria ceded to France all Habsburg lands and claims in Alsace and acknowledged French de facto sovereignty over the Three Bishoprics. Moreover, eager to emancipate themselves from Habsburg domination,

petty German states sought French protection. This anticipated the 1658

formation of the League of the Rhine, leading to the further diminution of Imperial power. As the Thirty Years' War petered out, a civil war — the Fronde — erupted.

It effectively checked France's ability to exploit the Peace of

Westphalia. Mazarin had largely pursued the policies of his predecessor, Cardinal Richelieu, augmenting the Crown's power at the expense of the nobility and the Parlements. The Frondeurs, political heirs of the turbulent feudal aristocracy, originally sought to protect their traditional feudal privileges from an increasingly centralized and

centralizing royal government. Furthermore, they believed their

traditional influence and authority was being usurped by the recently

ennobled (the Noblesse de Robe) who administered the Kingdom and on whom the Monarchy increasingly began to rely. This belief intensified their resentment. In 1648, Mazarin attempted to tax members of the Parlement de Paris. The members not only refused to comply, but also ordered all his earlier financial edicts burned. Buoyed by the victory of Louis, duc d’Enghien (later le Grand Condé) at Lens, Mazarin arrested certain members in a show of force. Ironically, Paris erupted in rioting.

A mob of angry Parisians broke into the royal palace and demanded to

see their king. Led into the royal bed chamber, they gazed upon Louis,

who was feigning sleep, were appeased and quietly departed. The threat

to the royal family and Monarchy prompted Anne to flee Paris with the King and his courtiers. Shortly thereafter, the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia allowed Condé's army to return to aid Louis and his court. As this first Fronde (Fronde parlementaire, 1648–1649) ended, a second (Fronde des princes,

1650–1653) began. Unlike that which preceded it, tales of sordid

intrigue and half-hearted warfare characterised this second phase of

upper-class insurrection. This rebellion represented to the aristocracy

a protest against and a reversal of their political demotion from vassals to courtiers. It was headed by the highest-ranking French nobles, from Louis's uncle, Gaston, duc d'Orléans, and first cousin, la Grande Mademoiselle; to more distantly-related Princes of the Blood, like Condé, his brother, Conti, and their sister, Anne-Geneviève de Bourbon, duchesse de Longueville; to dukes of legitimised royal descent, like Henri, duc de Longueville, and François, duc de Beaufort; and to princes étrangers, such as Frédéric Maurice, duc de Bouillon, and his brother, the famous Marshal of France, Turenne, as well as Marie de Rohan, duchesse de Chevreuse; and scions of France's oldest families, like François, duc de La Rochefoucauld. Louis's coming-of-age and subsequent coronation deprived the Frondeurs, claiming to act on his behalf and in his real interest against his mother and Mazarin, of their pretext for revolt. Thus, the Fronde gradually lost steam and ended in 1653, when Mazarin returned triumphant after having fled into exile on several occasions. On

Mazarin's death in 1661, Louis assumed personal control of the reins of

government. He was able to utilize the widespread public yearning for

peace, law and order, resulting from prolonged foreign war and domestic

civil strife, to further consolidate central political authority and

reforms at the feudal aristocracy's expense. Praising his ability to

wisely choose and encourage men of talent, Chateaubriand noted that "it

is the voice of genius of all kinds which sounds from the tomb of

Louis". Louis commenced his personal reign with administrative and fiscal reforms. In 1661, the treasury verged on bankruptcy. To rectify the situation, Louis chose Jean-Baptiste Colbert as Contrôleur général des Finances in 1665. However, Louis first had to eliminate Nicolas Fouquet, the Surintendant des Finances. Fouquet was charged with embezzlement. The Parlement found

him guilty and sentenced him to exile. However, Louis commuted the

sentence to life-imprisonment and also abolished Fouquet's post.

Although Fouquet's financial indiscretions were not really very

different from Mazarin before or Colbert after him, his ambition was

worrying to Louis. He built an opulent château at Vaux-le-Vicomte where

he lavishly entertained a comparatively poorer Louis. He appeared eager

to succeed Mazarin and Richelieu in assuming power, and indiscreetly

purchased and fortified Belle Île. These acts sealed his doom. Divested of Fouquet, Colbert reduced the national debt through more efficient taxation. The principal taxes included the aides and douanes (both customs duties), the gabelle (a tax on salt), and the taille (a tax on land). Louis and Colbert also had wide-ranging plans to bolster French commerce and trade. Colbert's mercantilist administration established new industries and encouraged manufacturers and inventors, such as the Lyon silk manufacturers and the Manufacture des Gobelins, a producer of tapestries. He also invited to France manufacturers and artisans from all over Europe, like Murano glassmakers,

Swedish iron workers, and Dutch shipbuilders. In this way, he aimed to

decrease foreign imports while increasing French exports, hence

reducing the net outflow of precious metals from France. Louis also instituted reforms in military administration through Le Tellier and his son Louvois.

They helped to curb the independent spirit of the nobility, imposing

order on them at court and in the army. Gone were the days when

generals protracted war at the frontiers, while bickering over

precedence and ignoring orders from the capital and the larger

politico-diplomatic picture. No longer too were senior positions and

rank the sole prerogative of the old military aristocracy (the Noblesse d'épée).

Louvois, in particular, pledged himself to modernizing the army,

re-organizing it into a professional, disciplined and well-trained

force. He was devoted to providing for the soldiers' material

well-being and morale, and even tried to direct campaigns. The law also did not escape Louis's attention, as is reflected in the numerous Grandes Ordonnances he enacted. Pre-revolutionary France was a patchwork of legal systems, with as many coutumes as there were provinces, and two co-existing legal traditions — customary law in the northern pays de droit coutumier and Roman civil law in the southern pays de droit écrit. The Grande Ordonnance de Procédure Civile of 1667, also known as Code Louis, was a comprehensive legal code attempting a uniform regulation of civil procedure throughout legally irregular France. It prescribed inter alia baptismal,

marriage and death records in the State's registers, not the Church's,

and also strictly regulated the right to remonstrance of the Parlements. The Code Louis played an important part in French legal history as the basis for the Code Napoléon, itself the origin of many modern legal codes. One of Louis's more infamous decrees was the Grande Ordonnance sur les Colonies of 1685, also known as Code Noir. Although it sanctioned slavery,

it did humanise the practice by prohibiting the separation of families.

Additionally, in the colonies, only Roman Catholics could own slaves,

and these had to be baptised.

The Sun King generously financed the royal court, and supported those who worked under him. He brought the Académie Française under his patronage, and became its "Protector". He allowed Classical French literature to flourish by protecting such writers as Molière, Racine and La Fontaine,

whose works greatly influence to this day. Louis also patronised the

visual arts by funding and commissioning various artists, such as Charles Le Brun, Pierre Mignard, Antoine Coysevox and Hyacinthe Rigaud whose works became famous throughout Europe. In music, composers and musicians, like Lully, Chambonnières and François Couperin thrived and influenced many others. Louis converted a hunting lodge built by Louis XIII into the spectacular royal Palace of Versailles through

four major building campaigns. Excepting the current chapel built in

the last decade of the reign, the third building campaign had already

given Versailles its present appearance. Louis officially moved the

royal court there on 6 May 1682. Versailles was a dazzling,

awe-inspiring setting for state affairs and the reception of foreign

dignitaries; the King alone assumed the attention, which was not shared

with the capital and people. Several reasons have been suggested for

the creation of the extravagant and stately palace, as well as the

relocation of the monarchy's seat. One such is that of contemporary

writer, Saint-Simon, who speculated that Louis viewed Versailles as an isolated power center where treasonous cabals could be more readily discovered and foiled. Alternatively, the Fronde caused

Louis to allegedly hate Paris, which was abandoned for a country

retreat; however, his many improvements, embellishments and

developments of Paris, such as the establishment of a police and

street-lighting, lend little credence to this theory. In Paris, Louis constructed the "Hôtel des Invalides" — a

military complex and home to this day for officers and soldiers

rendered infirm either by injury or age. While pharmacology was still

quite rudimentary, les Invalides pioneered new treatments and set new standards for hospice treatment. The conclusion of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1669 induced Louis to demolish the northern walls of Paris in 1670 and replace them with wide tree-lined boulevards. The Louvre and many other royal residences were also renovated and improved. Originally, Louis hired Bernini to

plan additions to the Louvre. However, these plans would have meant the

destruction of much of the existing structure, replacing it with an

Italian summer villa in

the centre of Paris. Bernini's plans were eventually shelved in favour

of Perrault's elegant colonnade. With the relocation of the court to

Versailles, the Louvre was given over to the Arts and the public. In June 1686, on the advice of his secret wife, Madame de Maintenon, Louis signed letters patent creating the "Institut de Saint-Louis" at Saint-Cyr for "filles pauvres de la noblesse" (poor noble girls) between the ages of seven and twenty. Construction

had begun two years previously. "Saint-Cyr" was at the time the only

educational institution for girls in France that was not a convent.

Admission of the 250 students was dependent on evidence documenting at

least four generations of nobility on their father's side. Mme de Maintenon took great pleasure in this school and was finally to die there. The death of Philip IV of Spain in

1665 precipitated the War of Devolution. In 1660, Louis had married

Philip IV's eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, as part of the Treaty of

the Pyrenees in 1659. The marriage treaty specified that Maria Theresa

was to renounce all claims to Spanish territory for herself and all her

descendants. However, Mazarin and Lionne had incorporated a word ("moyennant") making the renunciation conditional on the full payment of a Spanish dowry of 500,000 écus. This was never paid and would later play a part persuading Charles II of Spain to

leave his empire to Anjou (later Philip V of Spain) — the grandson of

Louis and Maria Theresa. Notwithstanding the non-payment of the dowry,

the War of Devolution had the "devolution" of lands as pretext. In Brabant,

children of the first marriage traditionally were not disadvantaged by

their parents’ remarriages, and still inherited property. Louis's wife

was Philip IV's daughter by his first marriage, while the new King of

Spain, Charles II, was his son by a subsequent marriage. Thus, Brabant

allegedly "devolved" on Maria Theresa. This excuse led to the War of

Devolution. Internal problems of the Dutch Republic aided Louis's designs on the Spanish Netherlands. The most prominent politician in the United Provinces at the time, Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary, feared the ambition of the young William III, Prince of Orange.

He feared the dispossession of supreme power and the restoration of the

House of Orange to the influence it had enjoyed before the death of William II, Prince of Orange.

However, shocked by the rapidity of French successes and fearful of the

future, the Dutch turned on their French allies and ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War with England. Joined by Sweden, they formed a Triple Alliance in

1668. The threat of escalation and a secret treaty partitioning the

Spanish succession with the Emperor, the other major claimant, induced

Louis to make peace. The Triple Alliance did not last very long. In 1670, Charles II of England, bribed by France, signed the secret Treaty of Dover,

allying with France. The two kingdoms, along with certain Rhineland

princes, declared war on the United Provinces in 1672, sparking off the Franco-Dutch War.

The rapid invasion and occupation of most of the Netherlands

precipitated a coup, toppling De Witt and placing William III in power.

While Spain, the Emperor and the rest of the Empire joined William III,

the English withdrew from the war by the Treaty of Westminster in 1674. Despite

diplomatic reverses, the French continued to triumph against

overwhelming opposing forces. A few weeks in 1674 saw the fall of the

Spanish territory of Franche-Comté to

French armies under Louis. Greatly outnumbered, Condé defeated

William III's coalition army, comprising Austrians, Spaniards and

Dutchmen, at the Battle of Seneffe,

forestalling a descent on Paris. In the 1674–1675 winter, the

outnumbered Turenne, conducting a daring and brilliant campaign, beat

the Imperial armies under Raimondo Montecuccoli, expelling them from Alsace across the Rhine,

and recovering the province. Through a series of feints, marches and

counter-marches at the close of the war, Louis besieged and captured Ghent,

a critical action dissuading the English Parliament from declaring war

on France. It also allowed Louis to impose peace on the allies in a

very superior position. After six years, war exhausted Europe, and

negotiations commenced, accomplished in 1678 with the Treaty of Nijmegen.

While Louis returned all captured Dutch territory, he gained more

territory in the Spanish Netherlands and retained Franche-Comté.

Thereafter, he intervened in the Scanian War, forcing Brandenburg-Prussia into the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Denmark-Norway into the Treaty of Fontainebleau and the Peace of Lund, all in 1679. Nijmegen further increased French influence in Europe, but did not satisfy Louis. He dismissed his foreign minister Simon Arnauld, marquis de Pomponne, in

1679, viewed as timorous and as having compromised too much with the

allies. Louis also maintained his army but, instead of pursuing his

claims through purely military action, he utilised judicial processes

to extend his territory further. The ambiguous nature of contemporary

treaties allowed Louis to claim the dependencies and lands of territory

ceded to him in previous treaties, but which effectively were distinct. Louis sought cities and territories such as Luxembourg and Casale, for their strategic position on the frontier, and access to the Po river valley in the heart of northern Italy respectively. He also desired Strasbourg, an important strategic outpost through which various Imperial armies

had previously crossed the Rhine into France. Strasbourg was a part of

Alsace, but had not been ceded with the rest of Habsburg-ruled Alsace

in the Peace of Westphalia. Louis seized these and other territories in

the period leading up to and during the War of the Reunions.

Infuriated by Louis's capture of parts of the Spanish Netherlands,

Spain declared war. However, abandoned by their Austrians allies and

minimally supported by the Dutch, the Spanish were quickly reduced,

and, by the Truce of Ratisbon in 1684, ceded most of the conquered territories to France for a duration of 20 years.

French colonies multiplied in the Americas, Asia and Africa. Descending down the Mississippi, discovered in 1673 by Jolliet and Marquette, Cavelier de La Salle claimed the vast Mississippi basin in 1682 and named it "Louisiane", after Louis. Meanwhile, diplomatic relations were initiated with distant countries. In 1669, Suleiman Aga led an Ottoman embassy, reviving the old Franco-Ottoman alliance. Moreover, in 1682, the Sultan of Morocco, Moulay Ismail, allowed consular and commercial establishments, and Moroccan ambassador Abdallah bin Aisha was sent to the court of Louis XIV in 1699. In 1715, Louis received a Persian embassy. Siam also dispatched an embassy in 1684, reciprocated by the French magnificently the next year under Chevalier de Chaumont. This, in turn, was succeeded by another Siamese embassy under Kosa Pan superbly received at Versailles in 1686. Another embassy was reciprocated in 1687 under Simon de la Loubère and French influence grew at the Siamese court, which granted France Mergui as a naval base. However, Narai's death and the execution of his pro-French minister Phaulkon ended this era of French influence in 1688 with the Siege of Bangkok. France also actively participated to the Jesuit China missions,

as Louis XIV sent in 1685 a mission of five Jesuit "mathematicians" to

China in an attempt to break the Portuguese predominance: Jean de Fontaney (1643–1710), Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), Jean-François Gerbillon (1654–1707), Louis Le Comte (1655–1728) and Claude de Visdelou (1656–1737). While French Jesuits were found at the court of the Manchu Kangxi Emperor in China, Louis received the visit of a Chinese Jesuit, Michael Shen Fu-Tsung, by 1684. Furthermore, several years later, he had at his court a Chinese librarian and translator — Arcadio Huang. By

the early 1680s, therefore, Louis had greatly augmented French

influence in the world. Domestically, he successfully increased the

Crown's influence and authority over the Church and aristocracy. Louis initially supported traditional Gallicanism, which limited papal authority in France, and convened an Assemblée du Clergé in November 1681. Before its dissolution eight months later, the Assembly had accepted the Declaration of the Clergy of France,

which increased royal authority at the expense of papal power. Without

royal approval, neither bishops could leave France nor appeals be made

to the Pope. Moreover, government officials could not be excommunicated

for acts committed in pursuance of their duties; and while the King

could make ecclesiastical law, all papal regulations without royal

assent were invalid in France. The Pope unsurprisingly repudiated the

Declaration. By

attaching them to his court, Louis also achieved increased control over

the French aristocracy. Pensions and privileges necessary to live in a

style appropriate to their rank were only possible by waiting

constantly on Louis. Moreover,

by entertaining, impressing and domesticating them with extravagant

luxury and other distractions, Louis expected them to remain under his

scrutiny. This prevented them from passing time on their own estates

and in their regional power-bases, from which they historically waged

local wars and plotted resistance to royal authority. Louis thus compelled and seduced the old military aristocracy (the noblesse d'épée) into becoming his ceremonial courtiers, further weakening their power. Louis's actions could find their rationale in the Fronde, which had resulted in his judging that royal power depended on commoners and relatively newer bureaucratic aristocrats (the nobles de robe),

who could be simply dismissed, filling the high executive offices,

rather than a grandee of ancient lineage whose entrenched influence was

more difficult to destroy. In fact, Louis's final victory over the nobility ensured the end of major French civil wars until the Revolution about

a hundred years later. Indeed, John A. Lynn calculated that a

significant reduction in years with civil war occurred after Louis. While the 1680s would see France becoming more isolated from its former allies,

by 1685, Louis's power did stand at its apogee. His policy of Reunions

had brought France to its greatest extent during his reign.

Furthermore, bombardment of the Barbary pirate strongholds of Algiers and Tripoli resulted

in favourable treaties and the liberation of Christian slaves. Also,

Genoese support of Spain in previous wars led Louis to command in 1684

the naval bombardment of Genoa. This produced Genoese submission and an official apology by the Doge at Versailles. Moreover,

Louis informed the Turks of his neutrality in an Austro-Turkish war and

even massed troops during the Reunions on the western frontier of the

Holy Roman Empire. Reassured, the Turkish allowed the 20-year Austro-Turkish Peace of Vasvár to lapse and moved on the offensive. Thus began the Great Turkish War in 1683 which would last till 1699 and which greatly distracted the Emperor from French endeavours. The Ottoman Grand Vizier nearly captured Vienna before being defeated by the King of Poland and his Polish-Imperial army. Notwithstanding the end of immediate danger to Vienna, however, Leopold I was still neither in a position to reverse Louis's gains by the Truce of Ratisbon nor able to fully concentrate on the War of the League of Augsburg later. Maria Theresa died

in 1683. On his queen's demise, Louis remarked that she had caused him

unease on no other occasion. She gave birth to six children. Only one

survived to adulthood, the eldest known as le Grand Dauphin or "Monseigneur". However, Louis had not remained faithful for long after their marriage in 1660. He took as mistresses Mademoiselle de La Vallière; Madame de Montespan; and Angélique de Fontanges. Consequently, he produced many illegitimate children, most of whom were married to members of cadet branches of the royal family. Nonetheless, Louis proved more faithful to his second wife, Madame de Maintenon, whom he secretly married probably on 10 October 1683 at Versailles. Although never announced or discussed publicly, this marriage was an open secret and would last until his death. The suggestion that Madame de Maintenon caused the persecution of Protestants and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which had awarded Huguenots political and religious freedom, is now being questioned. Louis

himself saw the persistence of Protestantism as a disgraceful reminder

of royal powerlessness; after all, the Edict was Henry IV's pragmatic

concession to end the longstanding Wars of Religion. Moreover, since the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, the prevailing contemporary European principle to assure socio-political stability was "cuius regio, eius religio" — the religion of the ruler should be the religion of the realm. Responding

to petitions, Louis initially excluded Protestants from office,

constrained the meeting of synods, closed churches outside Edict-stipulated areas, banned Protestant outdoor preachers, and

prohibited domestic Protestant migration. He also disallowed

Protestant-Catholic intermarriages if objections existed, encouraged

missions to the Protestants and rewarded converts to Catholicism. Despite

this discrimination, Protestants did not rebel, instead there occurred

a steady conversion of Protestants, especially the noble elites. However, in 1681, things changed. "cuius regio, euis religio"

generally had also meant that subjects who refused to convert could

emigrate. Louis banned emigration and effectively insisted all

Protestants must be converted. Secondly, following René de Marillac and Louvois's proposal, he began quartering dragoons in Protestant homes. While legal, the dragonnades inflicted

on Protestants severe financial strain and atrocious abuse. Between 300

000 and 400 000 Huguenots converted as it entailed financial rewards

and exemption from the dragonnades. On

15 October 1685, citing the extensive conversion of Protestants which

rendered privileges for the remainder redundant, Louis revoked the

Edict of Nantes with that of Fontainebleau. Louis

may have been seeking to placate the Catholic Church that chafed under

his numerous restrictions, or he may have acted to regain international

prestige after the defeat of the Turks without French aid, or even to

end the last remaining division in French society dating to the Wars of

Religion. Perhaps, he may have just been motivated by his coronation oath to eradicate heresy. In any case, the Edict of Fontainebleau exiled pastors, demolished churches, instituted forced baptisms and

banned Protestant groups. Defying royal decree, about 200 000 Huguenots

(roughly 27% of the Protestant population, or 1% of the French

population) fled France, taking with them their skills. Thus, some have

found the Edict very injurious to France. However,

others believe this an exaggeration; while many left, most of France's

preeminent Protestant businessmen and industrialists converted and

remained. The

reaction to the Revocation was mixed. French Catholic leaders

applauded, but Protestants across Europe were horrified, and even Pope Innocent XI, still arguing with Louis over Gallicanism, criticised the violence. The

War of the League of Augsburg (1688–1697) had two immediate causes with

French influence in the Rhineland at stake. First, the death of Charles II, Elector Palatine in 1685 caused a succession crisis, in which Louis's sister-in-law Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate had interests. The death of Max Henry, Archbishop of Cologne, produced another succession crisis in 1688. Moreover, growing concern about France led to the formation of the 1686 League of Augsburg by the Emperor, Spain, Sweden, Saxony and Bavaria; it intended to return France at least to its Treaty of Nijmegen borders. Conversely,

the Emperor's refusal to change Ratisbon into a permanent treaty

amplified Louis's fear that the Emperor's Balkan victories entailed an

imminent attack on the Reunions. Lastly, the birth of James II's son and Catholic heir, James Stuart, precipitated the "Glorious Revolution". Protestant William III of Orange sailed for England with troops despite Louis's warning that France would regard it as a casus belli.

James II was deposed, and his throne appropriated by his daughter and

son-in-law, Mary II and William III (now also of England). Vehemently

anti-French, William III pushed his new kingdoms into war, thus

transforming the League of Augsburg into the Grand Alliance.

In 1688, however, this was yet unsettled. Expecting the expedition to

absorb William III and his allies, Louis dispatched troops to the

Rhineland to compel confirmation of Ratisbon and acceptance of his

demands about the succession crises, as his ultimatum to the German

princes indicated. He also sought to protect his eastern provinces from

Imperial invasion by depriving the enemy army of sustenance, thus

explaining the pre-emptive devastation of much of southwestern Germany (the "Devastation of the Palatinate"). French

armies were generally victorious throughout the War because of Imperial

Balkan commitments, French logistical superiority which enabled a much

earlier campaign start, and the quality of French generals like

Condé's famous pupil, François Henri de Montmorency-Bouteville, duc de Luxembourg. His triumphs at Fleurus, Steenkerque and Neerwinden preserved northern France from invasion and dubbed him "le tapissier de Notre-Dame" for the numerous captured enemy standards he sent to decorate the Cathedral. Although the attempt to restore James II failed at the Battle of the Boyne, which led to the fall of Jacobite Ireland,

France accumulated a string of victories from Flanders in the north,

Germany in the east, Italy and Spain in the south, to the high seas and

the colonies. Louis personally supervised the capture of Mons and the reputedly impregnable fortress of Namur; and Luxembourg's capture of Charleroi gave France the defensive line of the Sambre. France also overran most of the Duchy of Savoy after Marsaglia and Staffarde. While naval stalemate ensued after the French victory at Beachy Head and the Allied victory at Barfleur-La Hougue, the Battle of Torroella exposed Catalonia to French invasion culminating in the capture of Barcelona. Although the Dutch captured Pondicherry, a French raid on the Spanish treasure port of Cartagena (in present-day Colombia) yielded a fortune of 10 000 000 livres.

In

1690, Sweden first offered to mediate. By 1692, both sides evidently

wanted peace, and secret bilateral talks had already begun. By the Treaty of Turin in 1696, which finally hastened the end of the War, Victor Amadeus, Duke of Savoy, separately concluded peace and switched sides. Thereafter, negotiations for a general peace began in earnest, culminating in the Treaty of Ryswick. The

Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 ended the War of the League of Augsburg, and

the Grand Alliance. By manipulating their rivalries and suspicions, Louis divided his enemies and broke their power. Although

Louis returned Catalonia and most of the Reunions, he secured permanent

French sovereignty over all of Alsace, including Strasbourg, thus

guaranteeing the Rhine as the Franco-German border to this day. Louis's

generosity to Spain despite French military superiority, which could

have resulted in more advantageous terms, has been read as a concession

to foster pro-French sentiment; it may ultimately have induced Charles II to name Louis's grandson, Philippe, duc d'Anjou, as heir. Besides the return of Pondicherry and Acadia, Louis's de facto possession of Saint-Domingue was

recognised. Compensated financially, he renounced interests in the

Electorate of Cologne and the Palatinate, and returned Lorraine to its

duke, albeit under restrictive terms allowing unhindered French

passage. The Treaty allowed the Dutch to garrison forts in the Spanish

Netherlands as a protective "Barrier" against possible French

aggression, and recognised William III and Mary II as joint sovereigns

of the British Isles. Consequently, Louis withdrew support for James II. The Treaty may not be as great a diplomatic defeat as it appears. Louis fulfilled many of his 1688 ultimatum aims. In any case, to him peace in 1697 was victory. The

Spanish succession finally came to the fore after the Treaty of

Ryswick. Charles II ruled a vast, much-prized empire, comprising Spain, Naples, Sicily, Milan, the Spanish Netherlands and numerous colonies. But he was severely inbred and had no direct heirs. The

main claimants were French and Austrian, and closely linked to Charles

II. The French claim was derived from Anne of Austria (Philip III of Spain's eldest daughter) and Marie-Thérèse (Philip IV's eldest daughter). Based on the laws of primogeniture, France had the better claim as it originated from eldest daughters in

each generation. However, the princesses’ renunciations to the throne

complicated matters; nevertheless, Marie-Thérèse's

renunciation was considered null and void owing to Spain's breach of

the marriage agreement. In contrast, no renunciation tainted Charles, Archduke of Austria's claims. He descended from Maria Anna (Philip III's youngest daughter). The English and Dutch feared that a French or Austrian-born Spanish king would threaten the balance of power and thus preferred the Bavarian Joseph Ferdinand, Leopold I's grandson, through his first wife Margaret Theresa of Spain (Philip IV's younger daughter). But, to appease the parties and avoid war, the First Partition Treaty divided the Italian territories between le Grand Dauphin and

the Archduke, awarding the rest of the empire to Joseph Ferdinand.

Presumably, the Dauphin's new territories would become part of France

when he succeeded Louis. Passionately

against his empire's dismemberment, Charles II reiterated his 1693

will, naming Joseph Ferdinand his sole successor. Sixth months later, the Bavarian died. Louis and William III again concluded a Partition Treaty, allocating Spain, the Low Countries and colonies to the Archduke, and Spanish lands in Italy to the Dauphin. Acknowledging

that his empire could only remain undivided by bequeathing it entirely

to a Frenchman or an Austrian, and pressured by his German wife, Maria Anna of Neuburg, Charles II named the Archduke Charles as sole heir. On

his deathbed in 1700, Charles II unexpectedly changed his will. Past

French military superiority, the pro-French faction and even Pope Innocent XII convinced him that France was more likely to preserve his empire intact. He thus offered the Dauphin's second son, Philippe de France,

the entire empire, provided it remained undivided. Anjou was not in the

direct line of French succession; thus his accession would not cause a

Franco-Spanish union. If Anjou refused, the throne would be offered to his younger brother, Charles de France, after which, to the Archduke Charles, and lastly, to the distantly-related House of Savoy. Louis

was confronted with a difficult choice. He could agree to the partition

and hopefully avoid a general war, or accept Charles II's will and

alienate others. Initially, Louis may have inclined towards abiding by

the partition treaties. However, the Dauphin's insistence persuaded

Louis otherwise. Moreover, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, marquis de Torcy, pointed

out that war with the Emperor would almost certainly ensue even if

Louis only accepted part of the Spanish inheritance. He emphasised

William III's unlikelihood to assist France in war because he "made a

treaty to avoid war and did not intend to go to war to implement the

treaty". Eventually, Louis decided to accept Charles II's will. Philippe, duc d'Anjou became Philip V, King of Spain. Most

European rulers accepted Philip V as King of Spain, though some only

reluctantly. Depending on one's views of the War as inevitable or not,

Louis acted reasonably or arrogantly. He

confirmed that Philip V retained his French rights despite his new

Spanish position. Admittedly, he may only have been hypothesising a

theoretical eventuality and not attempting a Franco-Spanish union.

However, Louis also sent troops to the Spanish Netherlands, evicting

the Dutch garrisons from the "Barrier" and securing Dutch recognition of Philip V. In 1701, he transferred the asien to to France, alienating English traders. He also acknowledged James Stuart,

James II's son, as king on the latter's death, infuriating William III.

These actions enraged Britain and the United Provinces. Consequently,

with the Emperor and the petty German states, they formed another Grand

Alliance, declaring war on France in 1702. French diplomacy, however,

retained Bavaria, Portugal and Savoy as Franco-Spanish allies. Beginning with Imperial aggression in Italy even before war was officially declared, the War of the Spanish Succession almost lasted till Louis's death, proving costly for him. Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy checked French initial success and broke the myth of French invincibility. Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy's victory at Blenheim caused Bavaria's occupation by the Palatinate and Austria, compelling Maximilian II Emanuel to flee to the Spanish Netherlands. Portugal and Savoy defected to the Allies after Blenheim. Later, Ramillies and Oudenarde precipitated the capture of the Low Countries and an invasion of France, and the Battle of Turin forced Louis to evacuate Italy, leaving it open to Allied armies. Defeats, famine and mounting debt greatly weakened France. Two massive famines struck

France between 1693 and 1710, killing over two million people. In both

cases the impact of harvest failure was exacerbated by wartime demands

on the food supply. By

the winter of 1708-1709, Louis became willing to accept peace at nearly

any cost. He agreed to surrender the entire Spanish empire to the

Archduke, and even to return all that he gained over sixty years in his

reign and revert to the frontiers of the Peace of Westphalia. However,

he stopped short of accepting the Allies’ inflexible requirement that

he attack his own grandson to force the humiliating terms on the

latter. Thus, the war continued. The

Allies could not overthrow Philip V in Spain as clearly as France could

not retain the entire Spanish inheritance. The Franco-Spanish victories

at Almansa, Villaviciosa and Brihuega definitively drove Allied forces from central Spain. Moreover, the Allied pyrrhic victory of Malplaquet revealed

the French difficult to defeat. At 21 000 casualties, the Allies

suffered double that of the French, who eventually fully recovered

their military pride at the decisive victory of Denain.

In 1705, Leopold I died. His elder son and successor, Joseph I,

followed him in 1711. The Archduke Charles subsequently inherited his

brother's Austrian lands. If the Spanish empire then fell to him, it

would have resurrected a domain as vast as that of Charles V.

To the Maritime Powers, this was as undesirable as the feared

Franco-Spanish union. Accordingly, Anglo-French talks began,

culminating in the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 between France, Spain,

Britain, and the Dutch. In 1714, after losing Landau and Freiburg, the

Emperor and Empire also made peace with France in the Treaty of Rastatt

and that of Baden. By

the general settlement, Philip V retained Spain and the colonies,

Austria received the Low Countries and divided Spanish Italy with

Savoy, and Britain kept Gibraltar and Minorca. Louis agreed to withdraw

his support for James Stuart, and ceded Newfoundland, Rupert's Land and

Acadia in the Americas to Britain. Admittedly, Britain gained the most

from the Treaty, but the final terms were very much more favourable to

France than those of 1709 and 1710. France retained Île-Saint-Jean and Île Royale, and notwithstanding Allied intransigence, was returned most of the captured Continental lands, preserving its antebellum frontiers. Louis even acquired additional territory, such as the Principality of Orange, and the Ubaye Valley,

which covered transalpine passes into Italy. Moreover, Louis secured

the rehabilitation to pre-war status and lands of his allies, the

Electors of Bavaria and of Cologne. After a reign of 72 years, Louis died of gangrene at Versailles on 1 September 1715, four days before his 77th birthday. Reciting the psalm Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina (O Lord, make haste to help me), Louis "yielded up his soul without any effort, like a candle going out". His body lies in Royal Basilica of Saint Denis outside Paris. The Dauphin had predeceased Louis in 1711, leaving three children — Louis, Duke of Burgundy; Philip V; and Charles, Duke of Berry. The eldest, Bourgogne, followed in 1712, and was himself soon followed by his elder son, Louis, Duke of Brittany. Thus, on Louis XIV's deathbed, his heir was his five-year-old great-grandson, Louis, Duke of Anjou, Burgundy's youngest son, and Dauphin after his grandfather's, father's and elder brother's deaths in short succession. Louis foresaw a minority and sought to restrict the power of his nephew, Philippe d'Orléans,

who as closest surviving legitimate relative in France would become the

prospective Louis XV's regent. Accordingly, he created a regency

council as Louis XIII did in anticipation of his own minority with some

power vested in his illegitimate son, Louis Auguste de Bourbon. Orléans, however, would have Louis's will annulled in the Parlement de Paris after his death and make himself sole Regent. He stripped Maine and his brother, Louis Alexandre de Bourbon, of the rank of "prince of the Blood", which Louis had given them, and significantly reduced Maine's power and privileges.