<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Marin Mersenne, 1588

- Composer Antonín Leopold Dvořák, 1533

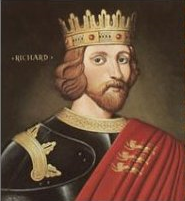

- King of England Richard I (the Lionheart), 1157

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 6 July 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Lord of Ireland, Lord of Cyprus, Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Count of Nantes, and Overlord of Brittany at various times during the same period. He was known as Cœur de Lion, or Richard the Lionheart, even before his accession, because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior. The Muslims (referred to as Saracens at the time) called him Melek-Ric or Malek al-Inkitar (King of England).

By age 16, Richard was commanding his own army, putting down rebellions in Poitou against his father, King Henry II. Richard was a central Christian commander during the Third Crusade, effectively leading the campaign after the departure of Philip Augustus and scoring considerable victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin. While he spoke very little English and spent very little time in England (he lived in his Duchy of Aquitaine, in the southwest of France), preferring to use his kingdom as a source of revenue to support his armies, he was seen as a pious hero by his subjects. He remains one of the very few Kings of England remembered by his epithet, not number, and is an enduring, iconic figure in England.

Richard was born on 8 September 1157, probably at Beaumont Palace. He was a younger brother of William IX, Count of Poitiers; Henry the Young King; and Matilda, Duchess of Saxony. As the third legitimate son of King Henry II of England, he was not expected to ascend the throne. He was also an elder brother of Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany; Leonora of England, Queen of Castile; Joan of England; and John, Count of Mortain, who succeeded him as king. Richard was the younger maternal half-brother of Marie de Champagne and Alix of France. Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine's oldest son, William IX, Count of Poitiers, died in 1156, before Richard's birth. Richard is often depicted as having been the favourite son of his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine. His father, Henry, was French and great-grandson of William the Conqueror. The closest English relation in Richard's family tree was Edith, wife of Henry I of England. Contemporary historian Ralph of Diceto traced his family's lineage through Edith to the Anglo-Saxon kings of England and Alfred the Great, and from there linked them to Noah and Woden. According to Angevin legend, there was even infernal blood in the family. While his father visited his lands from Scotland to France, Richard probably stayed in England. He was wet-nursed by a woman called Hodierna, and when he became king he gave her a generous pension. Little is known about Richard's education. Although born in Oxford, Richard could speak no English; he was an educated man who composed poetry and wrote in Limousin (lenga d'òc) and also in French. He

was said to be very attractive; his hair was between red and blond, and

he was light-eyed with a pale complexion. He was apparently of above

average height, according to Clifford Brewer he was 6 feet

5 inches (1.96 m) but his remains have been lost since at least the French Revolution,

and his exact height is unknown. From an early age he showed

significant political and military ability, becoming noted for his chivalry and

courage as he fought to control the rebellious nobles of his own

territory. His elder brother Henry was crowned king of England during

his father's lifetime, as Henry III. Historians have named this Henry

"the Young King" so as not to confuse him with the later Henry III of England, who was his nephew. The practice of marriage alliances was

common among medieval royalty: it allowed families to stake claims of

succession on each other's lands, and led to political alliances and

peace treaties. In March 1159 it was arranged that Richard would marry

one of the daughters of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona;

however, these arrangements failed, and the marriage never took place.

Richard's older brother Henry was married to Margaret, daughter of Louis VII of France and heiress to the French throne, on 2 November 1160. Despite this alliance between the Plantagenets and the Capetians, the dynasty on the French throne, the two houses were sometimes in conflict. In 1168, the intercession of Pope Alexander III was necessary to secure a truce between them. Henry II had conquered Brittany and taken control of Gisors and the Vexin, which had been part of Margaret’s dowry. Early in the 1160s there had been suggestions Richard should marry Alys (Alice),

second daughter of Louis VII; because of the rivalry between the kings

of England and France, Louis obstructed the marriage. A peace treaty

was secured in January 1169 and Richard’s betrothal to Alys was

confirmed. Henry

II planned to divide his kingdom between his sons, of which there were

three at the time; Henry would become King of England and have control

of Anjou, Maine, and Normandy, while Richard would inherit Aquitaine

from his mother and become Count of Poitiers, and Geoffrey would get

Brittany through marriage alliance with Constance, the heiress to the

region. At the ceremony where Richard's betrothal was confirmed, he

paid homage to the King of France for Aquitaine, thus securing ties of

vassalage between the two. After

he fell seriously ill in 1170, Henry II put in place his plan to divide

his kingdom, although he would retain overall authority of his sons and

their territories. In 1171, Richard left for Aquitaine with his mother

and Henry II gave him the duchy of Aquitaine at the request of Eleanor. Richard and his mother embarked on a tour of Aquitaine in 1171 in an attempt to placate the locals. Together they laid the foundation stone of St Augustine's Monastery in Limoges.

In June 1172 Richard was formally recognised as the Duke of Aquitaine

when he was granted the lance and banner emblems of his office; the

ceremony took place in Poitiers and was repeated in Limoges where he

wore the ring of St Valerie, who was the personification of Aquitaine.

According to Ralph of Coggeshall,

Henry the Young King was the instigator of rebellion against Henry II;

he wanted to reign independently over at least part of the territory

his father had promised him, and to break away from his dependence on

Henry II, who controlled the purse strings. Jean

Flori, an historian who specialises in the medieval period, believes

that Eleanor manipulated her sons to revolt against their father. Henry

the Young King abandoned his father and left for the French court,

seeking protection from Louis VII; he was soon followed by his younger

brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, while the 5-year-old John remained with

Henry II. Louis gave his support to the three sons and even knighted

Richard, tying them together through vassalage. The rebellion was described by Jordan Fantosme, a contemporary poet, as a "war without love". The

three brothers made an oath at the French court that they would not

make terms with Henry II without the consent of Louis VII and the

French barons. With

the support of Louis, Henry the Young King attracted the support of

many barons through promises of land and money; one such baron was Philip, Count of Flanders, who was promised £1,000 and several castles. The brothers had supporters in England, ready to rise up; led by Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester, the rebellion in England from Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, Hugh de Kevelioc, 5th Earl of Chester, and William I of Scotland. The alliance was initially successful, and by July 1173 they were besieging Aumale, Neuf-Marché, and Verneuil and Hugh de Kevelioc had captured Dol in Brittany. Richard went to Poitou and

raised the barons who were loyal to himself and his mother in rebellion

against his father. Eleanor was captured, so Richard was left to lead

his campaign in against Henry II's supporters in Aquitaine on his own.

He marched to take La Rochelle, but was rejected by the inhabitants; he withdrew to the city of Saintes which he established as a base of operations. In the meantime, Henry II had raised a very expensive army of over 20,000 mercenaries with which to face the rebellion. He

marched on Verneuil, and Louis retreated from his forces. The army

proceeded to recapture Dol and subdued Brittany. At this point, Henry

II made an offer of peace to his sons; on the advice of Louis the offer

was refused. Henry

II's forces took Saintes by surprise and captured much of its garrison,

although Richard was able to escape with a small group of soldiers. He

took refuge in Château de Taillebourg for the rest of the war. Henry

the Young King and the Count of Flanders planned to land in England to

assist the rebellion led by the Earl of Leicester. Anticipating this,

Henry II returned to England with 500 soldiers and his prisoners

(including Eleanor and his son's wives and fiancées), but

on his arrival found out that the rebellion had already collapsed.

William I of Scotland and Hugh Bigod were captured on 13 July and

25 July respectively. Henry II returned to France where he raised

the siege of Rouen,

where Louis VII had been joined by Henry the Young King after he had

abandoned his plan to invade England. Louis was defeated and a peace

treaty was signed in September 1174, with the Treaty of Montlouis. When Henry II and Louis VII made a truce on 8 September 1174, Richard was specifically excluded. Abandoned

by Louis and wary of facing his father's army in battle, Richard went

to Henry II's court at Poitiers on 23 September and begged for

forgiveness, weeping and falling at Henry's feet, who gave Richard the kiss of peace. Several days later, Richard's brothers joined him in seeking reconciliation with their father. The

terms the three brothers accepted were less generous than those they

had been offered earlier in the conflict (when Richard was offered four

castles in Aquitaine and half of the income from the duchy) and

Richard was given control of two castles in Pitou and half the income

of Aquitaine; Henry the Young King was given two castles in Normandy;

and Geoffrey was permitted half of Brittany. Eleanor would remain Henry

II's prisoner until his death, partly as insurance for Richard's good

behaviour. After

the conclusion of the war began the process of pacifying the provinces

that had rebelled against Henry II. He travelled to Anjou for this

purpose and Geoffrey dealt with Brittany. In January 1175, Richard was

dispatched to Aquitaine to punish the barons who had fought for him.

According to Roger of Howden's chronicle of Henry's reign, most of the

castles belonging to rebels were to be returned to the state they were

in 15 days before the outbreak of war, while others were to be

razed. Given

that by this time it was common for castles to be built in stone, and

that many barons had expanded or refortified their castles, this was

not an easy task. Gillingham

notes that Roger of Howden's chronicle is the main source for Richard's

activities in this period, although he notes that it records the

successes of the campaign; it was on this campaign that Richard acquired the name "Richard the Lionheart". The first such success was the siege of Castillon-sur-Agen.

The castle was "notoriously strong", but in a two-month siege the

defenders were battered into submission by Richard's siege engines. Henry

seemed unwilling to entrust any of his sons with resources that could

be used against him. It was suspected that Henry had appropriated Princess Alys, Richard's betrothed, the daughter of Louis VII of France by his second wife, as his mistress. This made a marriage between Richard and Alys technically impossible in the eyes of the Church, but Henry prevaricated: Alys's dowry, the Vexin, was valuable. Richard was discouraged from renouncing Alys because she was the sister of King Philip II of France, a close ally. After

his failure to overthrow his father, Richard concentrated on putting

down internal revolts by the nobles of Aquitaine, especially the

territory of Gascony.

The increasing cruelty of his reign led to a major revolt there in

1179. Hoping to dethrone Richard, the rebels sought the help of his

brothers Henry and Geoffrey. The turning point came in the Charente Valley in spring 1179. The fortress of Taillebourg was

well defended and was considered impregnable. The castle was surrounded

by a cliff on three sides and a town on the fourth side with a

three-layer wall. Richard first destroyed and looted the farms and

lands surrounding the fortress, leaving its defenders no reinforcements

or lines of retreat. The garrison sallied out of the castle and

attacked Richard; he was able to subdue the army and then followed the

defenders inside the open gates, where he easily took over the castle

in two days. Richard’s victory at Taillebourg deterred many barons

thinking of rebelling and forced them to declare their loyalty. It also

won Richard a reputation as a skilled military commander. In 1181-1182,

Richard faced a revolt over the succession to the county of Angoulême. His opponents turned to Philip II of France for support, and the fighting spread through the Limousin and Périgord. Richard was accused of numerous cruelties against his subjects, including rape. However, with support from his father and from the Young King, Richard succeeded in bringing the Viscount Aimar V of Limoges and Count Elie of Périgord to terms. After

Richard subdued his rebellious barons, he again challenged his father

for the throne. From 1180 to 1183 the tension between Henry and Richard

grew, as King Henry commanded Richard to pay homage to Henry the Young

King, but Richard refused. Finally, in 1183, Henry the Young King and

Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany invaded Aquitaine in an attempt to subdue

Richard. Richard’s barons joined in the fray and turned against their

duke. However, Richard and his army were able to hold back the invading

armies, and they executed any prisoners. The conflict took a brief

pause in June 1183 when the Young King died. However, Henry II soon

gave his youngest son John permission to invade Aquitaine. With the

death of Henry the Young King, Richard became the eldest son and heir

to the English crown, but still he continued to fight his father. To

strengthen his position, in 1187 Richard allied himself with 22-year-old Philip II, who was the son of Eleanor's ex-husband Louis VII by his third wife, Adele of Champagne. The historian John Gillingham has

suggested that theories that Richard was homosexual probably stemmed

from an official record announcing that, as a symbol of unity between

the two countries, the kings of France and England had slept overnight

in the same bed. He expressed the view that this was "an accepted

political act, nothing sexual about it; ... a bit like a modern-day

photo opportunity". In

exchange for Philip's help against his father, Richard promised to

concede to him his rights to both Normandy and Anjou. Richard paid

homage to Philip in November of the same year. With news arriving of the Battle of Hattin, he took the cross at Tours in the company of other French nobles. In

1188 Henry II planned to concede Aquitaine to his youngest son John.

The following year, Richard attempted to take the throne of England for

himself by joining Philip's expedition against his father. On 4 July

1189, Richard and Philip’s forces defeated Henry's army at Ballans.

Henry, with John's consent, agreed to name Richard his heir. Two days

later Henry II died in Chinon, and Richard succeeded him as King of

England, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou. Roger of Hoveden claimed

that Henry's corpse bled from the nose in Richard's presence, which was

taken as a sign that Richard had caused his death. Richard I was officially crowned duke on 20 July 1189 and king in Westminster Abbey on 13 September 1189. When

he was crowned, Richard barred all Jews and women from the ceremony,

but some Jewish leaders arrived to present gifts for the new king. According to Ralph of Diceto, Richard's courtiers stripped and flogged the Jews, then flung them out of court. When a rumour spread that Richard had ordered all Jews to be killed, the people of London began a massacre. Many Jews were beaten to death, robbed, and burned alive. Many Jewish homes were burned down, and several Jews were forcibly baptised. Some sought sanctuary in the Tower of London, and others managed to escape. Among those killed was Jacob of Orléans, one of the most learned of the age. Roger of Howeden, in his Gesta Regis Ricardi,

claimed that the rioting was started by the jealous and bigoted

citizens, and that Richard punished the perpetrators, allowing a

forcibly converted Jew to return to his native religion. Archbishop of Canterbury Baldwin of Exeter reacted by remarking, "If the King is not God's man, he had better be the devil's," a reference to the supposedly infernal blood in the House of Anjou. Realising

that the assaults could destabilise his realm on the eve of his

departure on crusade, Richard ordered the execution of those

responsible for the most egregious murders and persecutions. (But those

hanged were rioters who had accidentally burned down Christian homes). He distributed a royal writ demanding

that the Jews be left alone. However, the edict was loosely enforced,

as the following March there was further violence, including a massacre at York.

Richard had already taken the cross as Count of Poitou in 1187. His father and Philip II had done so at Gisors on 21 January 1188, after receiving news of the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin. Having become king, Richard and Philip agreed to go on the Third Crusade together, since each feared that, during his absence, the other might usurp his territories. Richard

swore an oath to renounce his past wickedness in order to show himself

worthy to take the cross. He started to raise and equip a new crusader

army. He spent most of his father's treasury (filled with money raised

by the Saladin tithe), raised taxes, and even agreed to free King William I of Scotland from his oath of subservience to Richard in exchange for 10,000 marks. To raise even more money he sold official positions, rights, and lands to those interested in them. Those already appointed were forced to pay huge sums to retain their posts. William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely and

the King's Chancellor, made a show of bidding £3,000 to remain as

Chancellor. He was apparently outbid by a certain Reginald the Italian,

but that bid was refused. Richard made some final arrangements on the continent. He reconfirmed his father's appointment of William Fitz Ralph to the important post of seneschal of

Normandy. In Anjou, Stephen of Tours was replaced as seneschal and

temporarily imprisoned for fiscal mismanagement. Payn de Rochefort, an

Angevin knight, was elevated to the post of seneschal of Anjou. In

Poitou, the ex-provost of Benon, Peter Bertin was made seneschal, and

finally in Gascony, the household official Helie de La Celle was picked

for the seneschalship there. After repositioning the part of his army

he left behind to guard his French possessions, Richard finally set out

on the crusade in summer 1190. (His delay was criticised by troubadours such as Bertran de Born.) He appointed as regents Hugh, Bishop of Durham, and William de Mandeville, 3rd Earl of Essex — who soon died and was replaced by Richard's chancellor William Longchamp. Richard's brother John was not satisfied by this decision and started scheming against William. Some

writers have criticised Richard for spending only six months of his

reign in England and siphoning the kingdom's resources to support his

crusade. Richard

claimed that England was "cold and always raining," and when he was

raising funds for his crusade, he was said to declare, "I would have

sold London if

I could find a buyer." However, although England was a major part of

his territories — particularly important in that it gave him a royal

title with which to approach other kings as an equal — it faced no major

internal or external threats during his reign, unlike his continental

territories, and so did not require his constant presence there. Like

most of the Plantagenet kings before the 14th century, he had no need to learn the English language.

Leaving the country in the hands of various officials he designated

(including his mother, at times), Richard was far more concerned with

his more extensive French lands. After all his preparations, he had an

army of 4,000 men-at-arms, 4,000 foot-soldiers, and a fleet of 100

ships. In September 1190 both Richard and Philip arrived in Sicily. After the death of King William II of Sicily, his cousin Tancred of Lecce had seized power and had been crowned early in 1190 as King Tancred I of Sicily, although the legal heir was William's aunt Constance, wife of the new Emperor Henry VI. Tancred had imprisoned William's widow, Queen Joan, who was Richard's sister, and did not give her the money she had inherited in William's will. When

Richard arrived, he demanded that his sister be released and given her

inheritance; she was freed on 28 September, but without the inheritance. The presence of foreign troops also caused unrest: in October, the people of Messina revolted, demanding that the foreigners leave. Richard attacked Messina, capturing it on 4 October 1190. After

looting and burning the city, Richard established his base there, but

this created tension between Richard and Philip Augustus. He

remained there until Tancred finally agreed to sign a treaty on 4 March

1191. The treaty was signed by Richard, Philip and Tancred. Its main terms were: The

two kings stayed on in Sicily for a while, but this resulted in

increasing tensions between them and their men, with Philip Augustus plotting with Tancred against Richard. The

two kings finally met to clear the air and reached an agreement,

including the end of Richard's bethroal to Philip's sister Alix (who

had supposedly been the mistress of Richard's father Henry II). In April 1191 Richard, with a large fleet, left Messina in order to reach Acre. But a storm dispersed the fleet. After some searching, it was discovered that the boat carrying his sister and his fiancée Berengaria was anchored on the south coast of Cyprus, together with the wrecks of several other ships, including the treasure ship. Survivors of the wrecks had been taken prisoner by the island's despot Isaac Komnenos. On 1 May 1191, Richard's fleet arrived in the port of Lemesos (Limassol) on Cyprus. He ordered Isaac to release the prisoners and the treasture. Isaac refused, so Richard landed his troops and took Limassol. Various princes of the Holy Land arrived in Limassol at the same time, in particular Guy of Lusignan. All declared their support for Richard provided that he support Guy against his rival Conrad of Montferrat. The

local barons abandoned Isaac, who considered making peace with Richard,

joining him on the crusade, and offering his daughter in marriage to

the person named by Richard. But Isaac changed his mind and tried to escape. Richard then proceeded to conquer the whole island, his troops being lead by Guy de Lusignan. Isaac surrendered and was confined with silver chains, because Richard had promised that he would not place him in irons. By 1 June, Richard had conquered the whole island. He named Richard de Camville and Robert of Thornham as governors. He later sold the island to the Knights Templar and it was subsequently acquired, in 1192, by Guy of Lusignan and became a stable feudal kindgom. The rapid conquest of the island by Richard is more important than it seems. The

island occupies a key strategic position on the maritime lanes to the

Holy Land, whose occupation by the Christians could not continue

without support from the sea. Cyprus remained a Christian stronghold until the battle of Lepanto (1571). Richard's exploit was well publicized and contributed to his reputation. Richard also derived significant financial gains from the conquest of the island. Richard left for Acre on 5 June, with his allies. Before leaving Cyprus, Richard married Berengaria, first-born daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. The wedding was held in Limassol on

12 May 1191 at the Chapel of St. George. It was attended by his sister

Joan, whom Richard had brought from Sicily. The marriage was celebrated

with great pomp and splendor, and many feasts and entertainments, and

public parades, and celebrations followed, to commemorate the event.

Among the other grand ceremonies was a double coronation. Richard

caused himself to be crowned King of Cyprus, and Berengaria Queen of

England and of Cyprus too. When Richard married Berengaria he was still

officially betrothed to Alys, and Richard pushed for the match in order

to obtain Navarre as

a fief like Aquitaine for his father. Further, Eleanor championed the

match, as Navarre bordered on Aquitaine, thereby securing her ancestral

lands' borders to the south. Richard took his new wife with him briefly

on this episode of the crusade. However, they returned separately.

Berengaria had almost as much difficulty in making the journey home as

her husband did, and she did not see England until after his death.

After his release from German captivity Richard showed some regret for his earlier conduct, but he was not reunited with his wife. King Richard landed at Acre on 8 June 1191. He gave his support to his Poitevin vassal Guy of Lusignan, who had brought troops to help him in Cyprus. Guy was the widower of his father's cousin Sibylla of Jerusalem and was trying to retain the kingship of Jerusalem, despite his wife's death during the Siege of Acre the previous year. Guy's claim was challenged by Conrad of Montferrat, second husband of Sibylla's half-sister, Isabella: Conrad, whose defence of Tyre had saved the kingdom in 1187, was supported by Philip of France, son of his first cousin Louis VII of France, and by another cousin, Duke Leopold V of Austria. Richard also allied with Humphrey IV of Toron, Isabella's first husband, from whom she had been forcibly divorced in 1190. Humphrey was loyal to Guy and spoke Arabic fluently,

so Richard used him as a translator and negotiator. Richard and his

forces aided in the capture of Acre, despite the king's serious

illness. At one point, while sick from scurvy, Richard is said to have picked off guards on the walls with a crossbow,

while being carried on a stretcher. Eventually, Conrad of Montferrat

concluded the surrender negotiations with Saladin and raised the

banners of the kings in the city. Richard quarrelled with Leopold V of Austria over the deposition of Isaac Komnenos (related to Leopold's Byzantine mother)

and his position within the crusade. Leopold's banner had been raised

alongside the English and French standards. This was interpreted as

arrogance by both Richard and Philip, as Leopold was a vassal of the Holy Roman Emperor (although

he was the highest-ranking surviving leader of the imperial forces).

Richard's men tore the flag down and threw it in the moat of Acre.

Leopold left the crusade immediately. Philip also left soon afterwards,

in poor health and after further disputes with Richard over the status

of Cyprus (Philip demanded half the island) and the kingship of

Jerusalem. Richard suddenly found himself without allies. Richard

had kept 2,700 Muslim prisoners as hostages against Saladin fulfilling

all the terms of the surrender of the lands around Acre. Philip, before

leaving, had entrusted his prisoners to Conrad, but Richard forced him

to hand them over to him. Richard feared his forces being bottled up in

Acre, as he believed his campaign could not advance with the prisoners

in train. He therefore ordered all the prisoners executed. He then

moved south, defeating Saladin's forces at the Battle of Arsuf on

7 September 1191. He attempted to negotiate with Saladin, but this was

unsuccessful. In the first half of 1192, he and his troops refortified Ascalon. An

election forced Richard to accept Conrad of Montferrat as King of

Jerusalem, and he sold Cyprus to his defeated protégé,

Guy. Only days later, on 28 April 1192, Conrad was stabbed to death by Hashshashin before he could be crowned. Eight days later, Richard's own nephew, Henry II of Champagne was married to the widowed Isabella,

although she was carrying Conrad's child. The murder has never been

conclusively solved, and Richard's contemporaries widely suspected his

involvement. Realising

that he had no hope of holding Jerusalem even if he took it, Richard

ordered a retreat. There commenced a period of minor skirmishes with

Saladin's forces while Richard and Saladin negotiated a settlement to

the conflict, as both realized that their respective positions were

growing untenable. Richard knew that both Philip and his own brother

John were starting to plot against him. However, Saladin insisted on

the razing of Ascalon's fortifications, which Richard's men had

rebuilt, and a few other points. Richard made one last attempt to

strengthen his bargaining position by attempting to invade Egypt — Saladin's

chief supply-base — but failed. In the end, time ran out for Richard. He

realised that his return could be postponed no longer, since both

Philip and John were taking advantage of his absence. He and Saladin

finally came to a settlement on 2 September 1192 — this included the

provisions demanding the destruction of Ascalon's wall as well as an

agreement allowing Christian access to and presence in Jerusalem. It

also included a three-year truce. Bad weather forced Richard's ship to put in at Corfu, in the lands of the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos,

who objected to Richard's annexation of Cyprus, formerly Byzantine

territory. Disguised as a Knight Templar, Richard sailed from Corfu

with four attendants, but his ship was wrecked near Aquileia, forcing Richard and his party into a dangerous land route through central Europe. On his way to the territory of Henry of Saxony, his brother-in-law, Richard was captured shortly before Christmas 1192, near Vienna, by Leopold V, Duke of Austria,

who accused Richard of arranging the murder of his cousin Conrad of

Montferrat. Moreover, Richard had personally offended Leopold by

casting down his standard from the walls of Acre. Richard and his

retainers had been travelling in disguise as low-ranking pilgrims, but

he was identified either because he was wearing an expensive ring, or

because of his insistence on eating roast chicken, an aristocratic

delicacy. Duke Leopold kept him prisoner at Dürnstein Castle.

His mishap was soon known to England, but the regents were for some

weeks uncertain of his whereabouts. While in prison, Richard wrote Ja nus hons pris or Ja nuls om pres ("No man who is imprisoned"), which is addressed to his half-sister Marie de Champagne. He wrote the song, in French and Occitan versions, to express his feelings of abandonment by his people and his sister. The detention of a crusader was contrary to public law, and on these grounds Pope Celestine III excommunicated Duke Leopold. Early in 1193, the Duke then handed Richard over to Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, who was aggrieved both by the support which the Plantagenets had given

to the family of Henry the Lion and also by Richard's recognition of

Tancred in Sicily, and who imprisoned him in Trifels Castle.

So Pope Celestine III excommunicated Henry VI as well for wrongfully

keeping Richard in prison. However, Henry needed the ransom money to

raise an army and assert his rights over southern Italy. Richard

famously refused to show deference to the emperor and declared to him,

"I am born of a rank which recognizes no superior but God". Despite his complaints, the conditions of his captivity were not severe. The

emperor demanded that 150,000 marks (65,000 pounds of silver) be

delivered to him before he would release the king, the same amount

raised by the Saladin tithe only a few years earlier, and

2–3 times the annual income for the English Crown under Richard.

Eleanor of Aquitaine worked to raise the ransom. Both clergy and laymen

were taxed for a quarter of the value of their property, the gold and

silver treasures of the churches were confiscated, and money was raised

from the scutage and the carucage taxes.

At the same time, John, Richard's brother, and King Philip of France

offered 80,000 marks for the Emperor to hold Richard prisoner until Michaelmas 1194. The emperor turned down the offer. The money to rescue the King was transferred to Germany by

the emperor's ambassadors, but "at the king's peril" (had it been lost

along the way, Richard would have been held responsible), and finally,

on 4 February 1194 Richard was released. Philip sent a message to John:

"Look to yourself; the devil is loose." The affair had a lasting influence on Austria, since part of the money from King Richard's ransom was used by Duke Leopold V to finance the founding in 1194 of the new city of Wiener Neustadt, which had a significant role in various periods of subsequent Austrian history up to the present.

During

his absence, John had come close to seizing the throne. Richard forgave

him when they met again and, bowing to political necessity, named him

as his heir in place of Arthur, whose mother Constance of Brittany was perhaps already open to the overtures of Philip II. When Philip attacked Richard's fortress, Chateau-Gaillard,

he boasted that "if its walls were iron, yet would I take it," to which

Richard replied, "If these walls were butter, yet would I hold them!" Determined

to resist Philip's designs on contested Angevin lands such as the Vexin

and Berry, Richard poured all his military expertise and vast resources

into war on the French King. He constructed an alliance against Philip,

including Baldwin IX of Flanders, Renaud, Count of Boulogne, and his father-in-law King Sancho VI of Navarre, who raided Philip's lands from the south. Most importantly, he managed to secure the Welf inheritance in Saxony for his nephew, Henry the Lion's son Otto of Poitou, who was elected Otto IV of Germany in 1198. Partly

as a result of these and other intrigues, Richard won several victories

over Philip. At Freteval in 1194, just after Richard's return from

captivity and money-raising in England to France, Philip fled, leaving

his entire archive of financial audits and documents to be captured by

Richard. At the battle of Gisors (sometimes called Courcelles) in 1198 Richard took "Dieu et mon Droit" — "God and my Right" — as his motto (still used by the British monarchy today), echoing his earlier boast to the Emperor Henry that his rank acknowledged no superior but God. In March 1199, Richard was in the Limousin suppressing a revolt by Viscount Aimar V of Limoges. Although it was Lent, he "devastated the Viscount's land with fire and sword". He besieged the puny, virtually unarmed castle of Chalus-Chabrol. Some chroniclers claimed that this was because a local peasant had uncovered a treasure trove of Roman gold, which Richard claimed from Aimar in his position as feudal overlord. In

the early evening of 25 March 1199, Richard was walking around the

castle perimeter without his chainmail, investigating the progress of

sappers on the castle walls. Arrows were occasionally shot from the

castle walls, but these were given little attention. One defender in

particular amused the king greatly — a man standing on the walls,

crossbow in one hand, the other clutching a frying pan which he had

been using all day as a shield to beat off missiles. He deliberately

aimed an arrow at the king, which the king applauded. However, another

arrow then struck him in the left shoulder near the neck. He tried to

pull this out in the privacy of his tent but failed; a surgeon, called

a 'butcher' by Hoveden, removed it, 'carelessly mangling' the King's

arm in the process. The wound swiftly became gangrenous. Accordingly, Richard asked to have the crossbowman brought before him; called alternatively Peter Basile, John Sabroz, Dudo, and

Bertrand de Gurdon (from the town of Gourdon) by chroniclers, the man

turned out (according to some sources, but not all) to be a boy. This

boy claimed that Richard had killed the boy's father and two brothers,

and that he had killed Richard in revenge. The boy expected to be

executed; Richard, as a last act of mercy, forgave the boy of his

crime, saying, "Live on, and by my bounty behold the light of day,"

before ordering the boy to be freed and sent away with 100 shillings. Richard then set his affairs in order, bequeathing all his territory to his brother John and his jewels to his nephew Otto. Richard

died on 6 April 1199 in the arms of his mother; it was later said that

"As the day was closing, he ended his earthly day." His death was later

referred to as 'the Lion (that) by the Ant was slain'. According to one

chronicler, Richard's last act of chivalry proved fruitless; in an orgy

of medieval brutality, the infamous mercenary captain Mercadier had the crossbow man flayed alive and hanged as soon as Richard died. Richard's heart was buried at Rouen in Normandy, the entrails in Châlus (where he died) and the rest of his body was buried at the feet of his father at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. A 13th century Bishop of Rochester wrote that Richard spent 33 years in purgatory as expiation for his sins, eventually ascending to Heaven in March 1232. Before 1948, no historian appears to have clearly affirmed that Richard was homosexual. However, modern historians generally accept that Richard was homosexual. But this was disputed by the reputable historian John Gillingham. The equally reputable historian Jean Flori analyses the available contemporaneous evidence in great detail, and concludes that Richard's two public confessions and penitences (in 1191 and 1195) must have referred to the sin of sodomy. Referring to contemporaneous accounts of Richard's relations with women, Flori concludes that Richard was probably bisexual.

Flori thus disagrees with and refutes Gillingham, although, he does

agree with Gillingham that the contemporaneous accounts do not support

the allegation that Richard had a homosexual relation with King Philip Augustus.