<Back to Index>

- Explorer Marco Polo, 1254

- Author Dame Agatha Christie, 1890

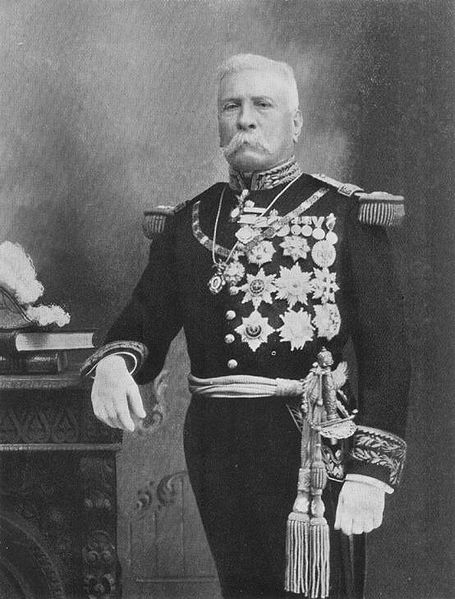

- President of Mexico José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori, 1830

José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori (September 15, 1830 – July 2, 1915) was a Mexican War volunteer and French intervention hero, an accomplished general and the President of Mexico continuously from 1876 to 1911, with the exception of a brief term in 1876 when he left Juan N. Méndez as interim president, and a four-year term served by his political ally Manuel González from 1880 to 1884. Commonly considered by historians to have been a dictator, he is a controversial figure in Mexican history. The period of his leadership was marked by significant internal stability (known as the "pax porfiriana"), modernization, and economic growth. However, Díaz's conservative regime grew unpopular due to repression and political continuity, and he fell from power during the Mexican Revolution, after he had imprisoned his electoral rival and declared himself the winner of an eighth term in office. The years in which Díaz ruled Mexico are referred to as the Porfiriato.

Porfirio Díaz was born on September 15, 1830, in Oaxaca, Mexico, to an indigenous mother and a Criollo father. His father, José de la Cruz was a modest innkeeper and died when his son was just an infant. Díaz

began training for the priesthood at the age of fifteen when his

mother, María Petrona Mori Cortés, sent him to the

Seminario Conciliar. In 1850, inspired by Liberal Benito Juárez, Díaz entered the Instituto de Ciencias and spent some time studying law. Díaz’s life took an unexpected turn, however, when he decided to join the armed forces upon the outbreak of war with the United States in 1846. Having

dabbled in many different professions, Díaz discovered his

vocation in 1855 and joined a band of liberal guerrillas who were

fighting a resurgent Antonio López de Santa Anna. Thus, his life as a military man began. Díaz’s military career is most noted for his service in the War of the Reform and the struggle against the French. By the time of the Battle of Puebla (May 5, 1862), General Díaz had become the brigade general in charge of an infantry brigade. During

the Battle of Puebla, his brigade was placed in the center between the

forts of Loreto and Guadalupe. From there, he repelled a French

infantry attack that was sent as a diversion to distract the Mexican

commanders' attention from the forts that were the main target of the

French army. In violation of the orders of General Ignacio Zaragoza,

General Díaz and his unit fought off a larger French force and

then chased after them. Despite Díaz’s inability to share

control, General Zaragoza commended the actions of General Díaz

during the battle as "brave and notable". In 1863, Díaz was captured by the French Army. He escaped and was offered by President Benito Juárez the

positions of secretary of defense or army commander in chief. He

declined both but took an appointment as commander of the Central Army.

That same year he was promoted to the position of Division General. In 1864, the conservatives supporting Emperor Maximilian asked

him to join the imperial cause. Díaz declined the offer. In

1865, he was captured by the Imperial forces in Oaxaca. He escaped and

fought the battles of Tehuitzingo, Piaxtla, Tulcingo and Comitlipa. In

1866, Díaz formally declared his loyalty to Juárez. That

same year he earned victories in Nochixtlan, Miahuatlan, and la

Carbonera, and once again captured Oaxaca. He was then promoted to

general. Also in 1866, Marshal Bazaine, commander of the Imperial forces, offered to surrender Mexico City to

Díaz if he withdrew support of Juárez. Díaz

declined the offer. In 1867, Emperor Maximilian offered Díaz the

command of the army and the imperial rendition to the liberal cause.

Díaz refused both. Finally, on April 2, 1867, he went on to win

the final battle for Puebla. When

Juárez became the president of Mexico in 1868 and began to

restore peace, Díaz resigned his military command and went home

to Oaxaca. However, it did not take long before the energetic

Díaz became unhappy with the Juarez administration. In

1871, Díaz attempted to lead a revolt against the reelection of

Juarez. In March 1872 Díaz’s forces were defeated in the battle

of La Bufa in Zacatecas. Following Juárez's death on July 9 of that year, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada assumed

the presidency and then offered amnesty to the rebels. Díaz

accepted in October and "retired" to the Hacienda de la Candelaria in Tlacotalpan, Veracruz.

However, he remained wildly popular among the people of Mexico well

after the defeat of the French and the death of Juárez in 1872. In 1874 he was elected to Congress from Veracruz. That year Lerdo de Tejada's government faced civil and military unrest, and offered Díaz the position of ambassador to Germany, which he refused. In 1875 Díaz traveled to New Orleans and Brownsville, Texas, to plan a rebellion, which was launched in Ojitlan, Oaxaca on January 10, 1876, as the "Plan de Tuxtepec". Díaz

continued to be an outspoken citizen and led a second revolt against

President Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada in 1876. In yet another failed

attempt to gain true political power, Díaz fled to the United

States of America. His fight, however, was far from over. Several months later, in November 1876, Díaz returned to his home country and fought the Battle of Tecoac,

where he defeated the government forces once and for all. Finally, in

May 1877, Díaz became the formally elected president of Mexico

for the first time. His campaign of "no-reelection", however, came to define his control over the state for more than thirty years. In 1870, Díaz ran as presidential candidate against President Juárez and Vice President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada.

In 1871 he made claims of fraud in the July elections won by

Juárez, who was confirmed as president by the Congress in

October. In response, Díaz launched the Plan de la Noria on November 8, supported by a number of rebellions across the nation. After

appointing himself president on November 28, 1876, he served only one

term — having staunchly stood against Lerdo's reelection policy. During

his first term in office, Díaz's son Raffah created a political

machine that held immense power over the people of Mexico. He

maintained control through manipulation of votes, but also through

simple violence and assassination of his opponents, who consequently

were few in number. His administration became famous for their

suppression of civil society and public revolts. Instead of running for

a second term, he handpicked his successor, Manuel González, one of his trustworthy companions. This sneaky side-step maneuver, however, did not mean that Díaz was stepping down from his powerful throne. The

four-year period that followed was marked by corruption and official

incompetence, so that when Díaz stepped up in the election of

1884, he was welcomed by his people with open arms. More

importantly, very few people remembered his "No Re-election" slogan

that defined his previous campaign. During this period the Mexican

underground political newspapers spread the new ironic slogan for the

Porfirian times, based on the slogan "Sufragio Efectivo, No Reelección" and changed it to "Sufragio Efectivo No, Reelección”.

In any case Díaz had the constitution amended, first to allow

two terms in office, and then to remove all restrictions on re-election. Having created a band of military brothers, Díaz went on to construct a broad coalition. He

was a cunning politician and knew very well how to manipulate people to

his advantage. A phrase used to describe the order of his rule was

"Pan, o palo", "Bread or a beating," (literally "Bread, or stick"),

meaning that one could either accept what was given willingly (often a

position of political power) or else face harsh consequences (often

death). Either way, rising opposition to Díaz’s administration

was immediately quelled. Over

the next twenty-six years as president, Díaz created a

systematic and methodical regime with a staunch military mindset. His

first goal was to establish peace throughout Mexico. According to John

A. Crow, Díaz "set out to establish a good strong pax

porfiriana, or Porfirian peace, of such scope and firmness that it

would redeem the country in the eyes of the world for its sixty-five

years of revolution and anarchy." His second goal was outlined in his motto — "little of politics and plenty of administration." In

reality he started a Mexican revolution; however, his fight for

profits, control, and progress kept his people in a constant state of

uncertainty. Díaz managed to dissolve all local authorities and

aspects of federalism that once existed. Not long after he became

president, the leaders of Mexico were answering directly to him. Those

who held high positions of power, such as members of the legislature,

were almost entirely his closest and most loyal friends. In his quest

for even more political control, Díaz even suppressed the media

and controlled the court system. In

order to secure his power, Díaz engaged in various forms of

co-optation and coercion. He played his people like a board game —

catering to the private desires of different interest groups and

playing off one interest against another. In order to satisfy any competing forces, such as the Mestizos, he gave them political positions of power that they could not deny. He did the same thing with the elite Criollo society

by not interfering with their wealth and haciendas. When it came to the

Roman Catholic Church, Díaz proved to be a different kind of

Liberal than those of the past. He neither assaulted the Church (like

most liberals) nor protected the Church. As

for the numerically dominant Indian population, they were almost

entirely ignored. In giving different groups with potential power a

taste of what they wanted, Díaz created the illusion of

democracy and quelled almost all competing forces. Díaz

knew that it was crucial for him to wield power over the countryside,

where the majority of Mexican citizens lived. Díaz depended on

the guardias rurales (police

of the countryside) to aid him in this matter. In essence, Díaz

worked to enhance the control of the government in the places where it

truly mattered — the military and the police. From 1892 onwards, Díaz's perennial opponent was the eccentric Nicolás Zúñiga y Miranda, who lost every election but always claimed fraud and considered himself to be the legitimately elected president of Mexico. As

Crow states, "It was the golden age of Mexican economics, 3.2 dollars

per peso. Mexico was compared economically to First World countries of

the time such as France, England, and Germany. For some Mexicans, there

was no money and the doors were thrown open to those who had." Also,

economic progress varied drastically from region to region. The north

was defined by mining and ranching while the central valley became the

home of large-scale farms for wheat and grain. Because

Díaz had created such an effective centralized government, he

was able to concentrate decision-making and maintain control over the

economic instability. On February 17, 1908, in an interview with the U.S. journalist James Creelman of Pearson's Magazine,

Díaz stated that Mexico was ready for democracy and elections

and that he would retire and allow other candidates to compete for the

presidency. Without

hesitation, several opposition and pro-government groups united to find

suitable candidates who would represent them in the upcoming

presidential elections. Many liberals formed clubs supporting the

governor of Nuevo León, Bernardo Reyes,

as a candidate for the presidency. Despite the fact that Reyes never

formally announced his candidacy, Díaz continued to perceive him

as a threat and sent him on a mission to Europe, so that he was not in the country for the elections. According

to John A. Crow, "A cautious but new breath entered the prostrate

Mexican underground. Dark undercurrents rose to the top." As groups began to settle on their presidential candidate, Díaz decided that he was not going to retire but rather allow Francisco Madero,

an aristocratic but democratically leaning reformer, to run against

him. Although Madero, a landowner, was very similar to Díaz in

his ideology, he hoped for other elites in Mexico to rule alongside the

president. Ultimately, however, Díaz did not approve of Madero

and had him jailed during the election in 1910. Notwithstanding what he

had formerly said about democracy and change, sameness seemed to be the

only reality. Despite

this, the election went ahead. Madero had gathered much popular support, but when the government announced the official results,

Díaz was proclaimed to have been re-elected almost unanimously,

with Madero gathering only a minuscule number of votes. This case of

massive electoral fraud aroused widespread anger throughout the Mexican citizenry. Madero called for revolt against Díaz, and the Mexican Revolution began. Díaz was forced from office and fled the country for France in 1911.

On July 2, 1915, after two marriages and three children, Díaz died in exile in Paris. He is buried there in the Cimetière du Montparnasse. In 1938, the 430-piece collection of arms of the late General Porfirio Díaz was donated to the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario.