<Back to Index>

- Mathematician James Waddell Alexander II, 1888

- Writer Sir William Gerald Golding, 1911

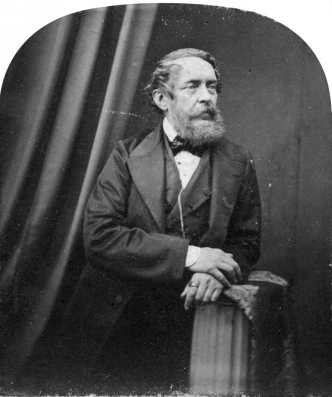

- Governor President of Hungary Lajos Kossuth, 1802

Lajos Kossuth (September 19, 1802 – March 20, 1894) was a Hungarian lawyer, journalist, politician and Governor-President of Hungary in 1849. He was widely honored during his lifetime, including in the United Kingdom and the United States, as a freedom fighter and bellwether of democracy in Europe.

Lajos Kossuth was born in Monok, Hungary, a small town in the county of Zemplén, as the oldest of four children. He was born into a Hungarian noble family. His father belonged to the lower nobility, had a small estate and was a lawyer by profession. The ancestors of the Kossuth family had lived in the county of Turóc (Slovak: Turiec) in the north of Hungary since the 13th century.The Slovak ancestry of Kossuth never became the topic of political debates because the family was part of the Hungarus nobility of the Kingdom of Hungary, Kossuth considered himself an ethnic Hungarian and stated that there was no Slovak nationality (also: "nation," "ethnic nation," "ethnicity") in the Kingdom of Hungary. The mother of Lajos Kossuth, Karolina Weber, was born to a Lutheran family. His mother raised the children as strict Lutherans. Kossuth studied at the Piarist college of Sátoraljaújhely and one year in the Calvinist college of Sárospatak and the University of Pest (now Budapest). Aged nineteen, he entered his father's legal practice. He was popular locally, and having been appointed steward to the countess Szapáry, a widow with large estates, he became her voting representative in the county assembly and settled in Pest. He was subsequently dismissed on the grounds of some misunderstanding in regards to estate funds.

Shortly after his dismissal by Countess Szapáry, Kossuth was appointed as deputy to Count Hunyady at the National Diet. The Diet met during 1825–1827 and 1832–1836 in Pressburg (Pozsony, present Bratislava), then capital of Hungary. Only the upper aristocracy could vote, however, and Kossuth took little part in the debates. At the time, a struggle to reassert a Hungarian national identity was beginning to emerge under able leaders – most notably Wesselényi and the Széchenyis. In part, this was also a struggle for reform against the stagnant Austrian government. Kossuth's duties to Count Hunyady included reporting on Diet proceedings in writing, as the Austrian government, fearing popular dissent, had banned published reports. The high quality of Kossuth's letters led to their being circulated in manuscript among other liberal magnates. Readership demands led him to edit an organized parliamentary gazette (Országgyűlési tudósítások); spreading his name and influence further. Orders from the Official Censor halted circulation by lithograph printing. Distribution in manuscript by post was forbidden by the government, although circulation by hand continued.

In 1836 the Diet was dissolved. Kossuth continued to report (in letter form), covering the debates of the county assemblies. This new-found publicity gave the assemblies national political prominence. Previously they had had little idea of each others' proceedings. His skilful embellishment of the speeches from the liberals and reformers enhanced the impact of his newsletters. The government attempted in vain to suppress the letters, and, other means having failed, he was arrested in May 1837, with Wesselényi and several others, on a charge of high treason. After spending a year in prison at Buda awaiting trial, he was condemned to four more years' imprisonment. His strict confinement damaged his health, but he was allowed to read. He greatly increased his political knowledge, and also acquired, from the study of the Bible and Shakespeare, a thorough knowledge of English.

The

arrests had caused great indignation. The Diet, which reconvened in

1839, demanded the release of the prisoners, and refused to pass any

government measures. Metternich long

remained obdurate, but the danger of war in 1840 obliged him to give

way. Wesselényi had been broken by his imprisonment, but

Kossuth, partly supported by the frequent visits of Teresa Meszleny,

emerged from prison unbroken. Immediately after his release, Kossuth

and Meszleny were married, and she remained a firm supporter of his

politics. Although Meszleny was a Catholic, Roman Catholic priests

refused to bless the marriage, as Kossuth, a Protestant, would not

convert. This experience influenced Kossuth's firm defense of mixed marriages. Kossuth had now become a national icon. He regained full health in January 1841 and was appointed editor of Pesti Hírlap,

a new Liberal party newspaper. Notably, the government agreed to grant

a licence. The paper achieved unprecedented success, soon reaching the

then immense circulation of 7000 copies. A competing pro-government

newspaper, Világ, started up, but it only served to increase Kossuth's visibility and add to the general political fervour. Széchenyi,

the great reformer, publicly warned Kossuth that his appeals to the

passions of the people would lead the nation to revolution. Kossuth,

undaunted, did not stop at the publicly reasoned reforms demanded by

all Liberals: the abolition of entail, the abolition of feudal burdens

and taxation of the nobles. He went on to broach the possibility of

separating from Austria. By combining this nationalism with an

insistence on the superiority of the Magyars to the Slavonic inhabitants of Hungary, he sowed the seeds of both the collapse of Hungary in 1849 and his own political demise. In 1844, Kossuth was dismissed from Pesti Hírlap after

a dispute with the proprietor over salary. It is believed that the

dispute was rooted in government intrigue. Kossuth was unable to obtain

permission to start his own newspaper. In a personal interview, Metternich offered

to take him into the government service. Kossuth refused and spent the

next three years without a regular position. He continued to agitate on

behalf of both political and commercial independence for Hungary. He

adopted the economic principles of List, and was the founder of a

"Védegylet" society – whose members consumed only Hungarian

produce. He also argued for the creation of a Hungarian port at Fiume (Rijeka). In autumn 1847, Kossuth was able to take his final key step. Due to the support of Lajos Batthyány during a keenly fought campaign, he was elected to the new Diet as member for Pest.

He proclaimed: "Now that I am a deputy, I will cease to be an

agitator." He immediately became chief leader of the Extreme Liberals. Ferenc Deák was absent. Batthyány, István Széchenyi, Szemere and József Eötvös,

his political rivals, felt that his personal ambition and egoism led

him to assume the chief place, and to use his parliamentary position to

establish himself as leader of the nation; but before his eloquence and

energy all apprehensions were useless. His eloquence was of that

nature, in its impassioned appeals to the strongest emotions, that it

required for its full effect the highest themes and the most dramatic

situations. In a time of rest, though he could never have been obscure,

he would never have attained the highest power. It was therefore a

necessity of his nature, perhaps unconsciously, always to drive things

to a crisis. The crisis came, and he used it to the full. On March 3, 1848, shortly after the news of the revolution in Paris had

arrived, in a speech of surpassing power he demanded parliamentary

government for Hungary and constitutional government for the rest of

Austria. He appealed to the hope of the Habsburgs, "our beloved Archduke Franz Joseph"

(then seventeen years old), to perpetuate the ancient glory of the

dynasty by meeting half-way the aspirations of a free people. He at

once became the leader of the European revolution; his speech was read

aloud in the streets of Vienna to the mob by which Metternich was

overthrown (March 13), and when a deputation from the Diet visited

Vienna to receive the assent of Emperor Ferdinand to their petition it

was Kossuth who received the chief ovation. Lajos Batthyány, who formed the first responsible government, appointed Kossuth the Minister of Finance. With

amazing energy he began developing the internal resources of the

country: re-establishing a separate Hungarian coinage, and using every

means to increase national self-consciousness. Characteristically, the

new Hungarian bank notes had Kossuth's name as the most prominent

inscription; making reference to "Kossuth Notes" a future byword. A new

paper was started, to which was given the name of Kossuth Hirlapja,

so that from the first it was Kossuth rather than the Palatine or prime

minister Batthyány whose name was in the minds of the people

associated with the new government. Much more was this the case when,

in the summer, the dangers from the Croats, Serbs and the reaction at

Vienna increased. In a great speech July 11 he asked that the nation

should arm in self-defence, and demanded 200,000 men; amid a scene of

wild enthusiasm this was granted by acclamation. However, the danger

had been exacerbated by Kossuth himself, through appealing exclusively

to the Magyar notables rather than the other subject minorities of the

Habsburg empire. The Austrians, meanwhile, successfully used the other

minorities as allies against the Magyar uprising. Kossuth's

interpretation of the role of the non-Hungarian ethnic groups - as

recounted in his speeches - was that Habsburg sympathizers "stirred up

the Wallachian peasants to take up arms against their own

constitutional rights ... aided by the rebellious Servian hordes."

These communities duly "commenced a course of Vandalism and extinction,

sparing neither women, children, nor aged men; murdering and torturing

the defenceless Hungarian inhabitants; burning the most flourishing

villages and towns." While Croatian ban Josip Jelačić was

marching on Pest, Kossuth went from town to town rousing the people to

the defence of the country, and the popular force of the Honvéd was

his creation. When Batthyány resigned he was appointed with

Szemere to carry on the government provisionally, and at the end of

September he was made President of the Committee of National Defence. From

this time he had increased amounts of power. The direction of the whole

government was in his hands. Without military experience, he had to

control and direct the movements of armies; he was unable to keep

control over the generals or to establish that military co-operation so

essential to success. Arthur Görgey in

particular, whose great abilities Kossuth was the first to recognize,

refused obedience; the two men were very different personalities. Twice

Kossuth deposed him from the command; twice he had to restore him. It

would have been well if Kossuth had had something more of Görgey's

calculated ruthlessness, for, as has been truly said, the revolutionary

power he had seized could only be held by revolutionary means (by which

it is usually meant, revolutions can only be effected by dictatorship,

repression and bloodshed); but he was by nature soft-hearted and always

merciful; though often audacious, he lacked decision in dealing with

men. It has been said that he showed a want of personal courage; this

is not improbable, the excess of feeling which made him so great an

orator could hardly be combined with the coolness in danger required of

a soldier; but no one was able, as he was, to infuse courage into

others. During

all the terrible winter which followed, his energy and spirit never

failed him. It was he who overcame the reluctance of the army to march

to the relief of Vienna; after the defeat at the Battle of Schwechat, at which he was present, he sent Józef Bem to carry on the war in Transylvania. At the end of the year, when the Austrians were approaching Pest, he asked for the mediation of Mr Stiles, the American envoy. Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, however, refused all terms, and the Diet and government fled to Debrecen, Kossuth taking with him the Crown of St Stephen,

the sacred emblem of the Hungarian nation. In November 1848, Emperor

Ferdinand abdicated in favour of Franz Joseph. The new Emperor revoked

all the concessions granted in March and outlawed Kossuth and the

Hungarian government - set up lawfully on the basis of the April laws. In April 1849, when the Hungarians had won many successes, after sounding the army, he issued the celebrated Hungarian Declaration of Independence,

in which he declared that "the house of Habsburg-Lorraine, perjured in

the sight of God and man, had forfeited the Hungarian throne." It was a

step characteristic of his love for extreme and dramatic action, but it

added to the dissensions between him and those who wished only for

autonomy under the old dynasty, and his enemies did not scruple to

accuse him of aiming for Kingship. The dethronement also made any

compromise with the Habsburgs practically impossible. For

the time the future form of government was left undecided, and Kossuth

was appointed regent-president (to satisfy both royalists and

republicans). Kossuth played a key role in tying down the Hungarian

army for weeks for the siege and recapture of Buda castle, finally

successful on 4 May 1849. The hopes of ultimate success were, however,

frustrated by the intervention of Russia; all appeals to the western

powers were vain, and on August 11 Kossuth abdicated in favor of

Görgey, on the ground that in the last extremity the general alone

could save the nation. Görgey capitulated at Világos (now Şiria,

Romania) to the Russians, who handed over the army to the Austrians.

Görgey was spared – at the insistence of the Russians. Reprisals

were taken on the rest of the Hungarian army. Kossuth steadfastly

maintained until his death that Görgey alone was responsible for

the humiliation. Kossuth's time in power was at an end. A solitary fugitive, he crossed the Ottoman frontier. He was hospitably received by the Ottoman authorities, who, supported by the British,

refused, notwithstanding the threats of the allied emperors, to

surrender him and other fugitives to Austria. In January 1850 he was

removed from Vidin, where he had been kept under house arrest, to Shumla, and thence to Kütahya in Asia Minor.

Here he was joined by his children, who had been confined at Pressburg

(present day Bratislava); his wife (a price had been set on her head)

had joined him earlier, having escaped in disguise. In September 1851 he was allowed to leave the Ottoman Empire on the American frigate Mississippi. He first landed at Marseille, where he received an enthusiastic welcome from the people, but the Prince-President Louis Napoleon refused to allow him to cross France. On October 23 he landed at Southampton and

spent three weeks in Britain, where he was generally feted. Addresses

were presented to him at Southampton, Birmingham and other towns; he

was officially entertained by the Lord Mayor of the City of London; at each place he spoke eloquently in English for the Hungarian cause; and he indirectly caused Queen Victoria to

stretch the limits of her constitutional power over her Ministers to

avoid embarrassment, and eventually helped cause the fall of the

government in power. Having learnt English during an earlier political imprisonment with the aid of a volume of Shakespeare, his spoken English was 'wonderfully archaic' and theatrical. The Times,

generally cool towards the revolutionaries of 1848 in general and

Kossuth in particular, nevertheless reported that his speeches were

'clear' and that a three-hour talk was not unusual for him; and also,

that if he was occasionally overcome by emotion when describing the

defeat of Hungarian aspirations, 'it did not at all reduce his

effectiveness'. At Southampton, he was greeted by a crowd of thousands

outside the Lord Mayor's balcony, who presented him with a flag of the

Hungarian Republic. The City of London Corporation accompanied him in procession through the City, and the way to the Guildhall was lined by thousands of cheering people. He went thereafter to Winchester, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham; at Birmingham the crowd that gathered to see him ride under the

triumphal arches erected for his visit was described, even by his

severest critics, as 75,000 individuals. Back in London he addressed the Trades Unions at Copenhagen Fields in Islington. Some twelve thousand 'respectable artisans' formed a parade at Russell Square and marched out to meet him. At the Fields themselves, the crowd was enormous; the Times estimated it conservatively at 25,000, while the Morning Chronicle described it as 50,000, and the demonstrators themselves 100,000. The Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston,

who had already proved himself a friend of the losing sides in several

of the failed revolutions of 1848, was determined to receive him at his

country house, Broadlands. The Cabinet had

to vote to prevent it; Queen Victoria reputedly was so incensed by the

possibility of her Foreign Secretary supporting an outspoken republican

that she asked the Prime Minister, Lord John Russell for

Palmerston's resignation, but Russell claimed that such a dismissal

would be drastically unpopular at that time and over that issue. When

Palmerston upped the ante by receiving at his house, instead of

Kossuth, a delegation of Trade Unionists from Islington and Finsbury,

and listened sympathetically as they read an address that praised

Kossuth and declared the Emperors of Austria and Russia 'despots,

tyrants and odious assassins', it was noted as a mark of indifference

to Royal displeasure. This, together with Palmerston's support of Louis Napoleon, caused the Russell government to fall. From Britain he went to the United States of America: there his reception was equally enthusiastic, if less dignified. Henry David Thoreau commented that this excitement was due to superficial politicians joining Kossuth's political bandwagon. He was the second foreign citizen to make a speech in the National Statuary Hall (Lafayette being the first). Prior to arrival he received the support of abolitionists, freemasons and Protestants, while Catholics (especially Irish) and pro-slavery groups opposed him. Secretary of State Daniel Webster wanted Kossuth's help in the upcoming presidential election, and spoke of seeing the American Republican model develop in Hungary, although President Millard Fillmore apologised to the Austrian chargé d'affaires for what he explained was an individual unofficial opinion. His ship was greeted with a hundred-gun salute when it passed Jersey City and hundreds of thousands of people came to see him set foot in New York. Heralded as the Hungarian Washington, he was given a congressional Banquet and received at the White House and the House of Representatives. Following his refusal to condemn slavery, William Lloyd Garrison wrote a book-length open letter to him denouncing him as a criminal. In

1856, Kossuth toured Scotland extensively, giving lectures in major

cities and small towns alike. Gradually,

his autocratic style and uncompromising outlook destroyed any real

influence among the expatriate community. Other Hungarian exiles

protested against his appearing to claim to be the only national hero

of the revolution. Count Casimir Batthyány attacked him in The Times, and Szemere,

who had been prime minister under him, published a bitter criticism of

his acts and character, accusing him of arrogance, cowardice and

duplicity. He soon returned to England, where he lived for eight years in close connection with Giuseppe Mazzini,

by whom, with some misgiving, he was persuaded to join the

Revolutionary Committee. Quarrels of a kind only too common among

exiles followed. Hungarians were especially offended by his continuing

use of the title of Regent. He

watched with anxiety every opportunity of once more freeing his country

from Austria. An attempt to organize a Hungarian legion during the

Crimean War was stopped; but in 1859 he entered into negotiations with Napoleon III, left England for Italy and began the organization of a Hungarian legion, which was to make a descent on the coast of Dalmatia. The Peace of Villafranca made this impossible. From then on, Kossuth remained in Italy. He refused to follow the other Hungarian patriots, who, under the lead of Deák, negotiated the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867,

and the ensuing amnesty. It is doubted whether Emperor Franz Joseph

would have allowed the amnesty to extend to Kossuth. Publicly,

Kossuth remained unreconciled to the house of Habsburg, and committed

to a fully independent state. Though elected to the Diet of 1867, he

never took his seat. He continued to remain a widely popular figure,

but did not allow his name to be associated with dissent or any

political cause. A law of 1879, which deprived of citizenship all

Hungarians who had voluntarily been absent ten years, was a bitter blow

to him. He displayed no interest in benefitting from a further amnesty

in 1880. In 1890, a delegation of Hungarian pilgrims in Turin recorded a short patriotic speech delivered by the elderly Lajos Kossuth. The original recording on two wax cylinders for the Edison phonograph survives to this day, although barely audible due

to excess playback and unsuccessful early restoration attempts. Lajos

Kossuth is the earliest born person in the world who has his voice

preserved. He died in Turin on 20 March 1894; his body was taken to Budapest, where he was buried amid the mourning of the whole nation, Mór Jókai delivering the funeral oration. A bronze statue was erected, by public subscription, in the Kerepesi Cemetery.

Many regard Kossuth as Hungary's purest patriot and greatest orator.

Others saw him as, unwittingly, the author of Hungary's subjugation

rather than its independence.

In addition, the indignation which he aroused against Russian policy had much to do with the strong anti-Russian feeling which made the Crimean War possible.