<Back to Index>

- Surgeon William Stewart Halsted, 1852

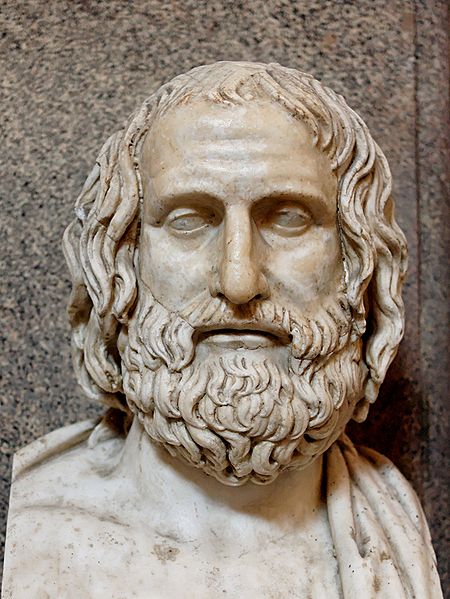

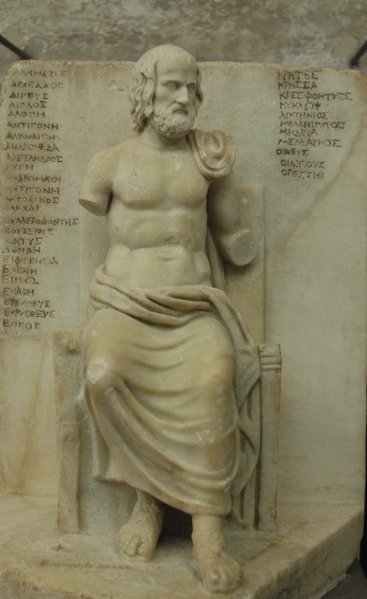

- Playwright Euripides, 480 B.C.

- Prime Minister of Italy Aldo Moro, 1916

Euripides (Ancient Greek: Εὐριπίδης) (ca. 480 BCE – 406 BCE) was the last of the three great tragedians of classical Athens (the other two being Aeschylus and Sophocles). Ancient scholars thought that Euripides had written ninety-five plays, although four of those were probably written by Critias. Eighteen or nineteen of Euripides' plays have survived complete. There has been debate about his authorship of Rhesus, largely on stylistic grounds and ignoring classical evidence that the play was his. Fragments, some substantial, of most of the other plays also survive. More of his plays have survived than those of Aeschylus and Sophocles together, because of the unique nature of the Euripidean manuscript tradition.

Euripides is known primarily for having reshaped the formal structure of Athenian tragedy by portraying strong female characters and intelligent slaves and by satirizing many heroes of Greek mythology.

His plays seem modern by comparison with those of his contemporaries,

focusing on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way

previously unknown to Greek audiences. Little

is known about Euripides, and most recorded sources are based on legend

and hearsay. According to one legend, Euripides was born in Salamís on 23 September 480 BCE, the day of the Persian War's

greatest naval battle. Other sources estimate that he was born as early

as 485 BCE. His father's name was either Mnesarchus or Mnesarchides and

his mother's name was Cleito. Evidence suggests that the family was wealthy and influential. It is recorded that he served as a cup-bearer for Apollo's dancers, but he grew to question the religion he grew up with, exposed as he was to thinkers such as Protagoras, Socrates, and Anaxagoras. He was married twice, to Choerile and Melito, though sources disagree as to which woman he married first. He had three sons and it is rumored that he also had a daughter who was killed after a rabid dog attacked her (some say this was merely a joke made by Aristophanes, who often poked fun at Euripides). The record of Euripides' public

life, other than his involvement in dramatic competitions, is almost

non-existent. The only reliable story of note is one by Aristotle about

Euripides' involvement in a dispute over a liturgy (an account that

offers strong evidence that Euripides was a wealthy man). It has been

said that he traveled to Syracuse, Sicily; that he engaged in various public or political activities during his lifetime; that he wrote his tragedies in a sanctuary, The Cave of Euripides on Salamis Island; and that he left Athens at the invitation of King Archelaus I of Macedon and stayed with him in Macedonia and

allegedly died there in 406 B.C. after being accidentally attacked by

the king's hunting dogs while walking in the woods. According to Pausanias, Euripides was buried in Macedonia. Euripides first competed in the City Dionysia, the famous Athenian dramatic festival, in 455 BCE, one year after the death of Aeschylus.

He came third, reportedly because he refused to cater to the fancies of

the judges. It was not until 441 BCE that he won first prize and over

the course of his lifetime Euripides claimed only four victories. He

also won a posthumous victory. He was a frequent target of Aristophanes' humour. He appears as a character in The Acharnians, Thesmophoriazusae, and most memorably in The Frogs (where Dionysus travels to Hades to bring Euripides back from the dead; after a competition of poetry, the god opts to bring Aeschylus instead). Euripides'

final competition in Athens was in 408 BCE; there is a story that he

left Athens embittered over his defeats. He accepted an invitation by

the king of Macedon in 408 or 407 BCE, and once there he wrote Archelaus in

honour of his host. He is believed to have died there in winter 407/6

BCE; ancient biographers have told many stories about his death, but

the simple truth was that it was probably his first exposure to the

harsh Macedonia winter which killed him. The Bacchae was performed after his death in 405 BCE and won first prize. In comparison with Aeschylus (who won thirteen times) and Sophocles (who

had eighteen victories) Euripides was the least honoured of the three,

at least in his lifetime. Later in the 4th century BCE, Euripides'

plays became the most popular, largely because of the simplicity of

their language. His works influenced New Comedy and Roman drama, and were later idolized by the French classicists; his influence on drama extends to modern times. Euripides' greatest works include Alcestis, Medea, Trojan Women, and The Bacchae. Also considered notable is Cyclops, the only complete satyr play to have survived. While

the seven plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles that have survived were

those considered their best, the manuscript containing Euripides' plays

was part of a multiple volume, alphabetically arranged collection of

Euripides' works, rediscovered after lying in a monastic collection for

approximately 800 years. The manuscript contains those plays whose

(Greek) titles begin with the letters E to K. This accounts for the

large number of extant plays of Euripides (among ancient dramatists,

only Plautus has

more surviving plays), the survival of a satyr play, and the absence of

a trilogy. It is a testament to the quality of Euripides' plays that,

though their survival was dependent on the letter their title began

with and not (as with Aeschylus and Sophocles) their quality, they are

ranked alongside and often above the plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles. In June 2005, classicists at Oxford University worked on a joint project with Brigham Young University, using multi-spectral imaging technology to recover previously illegible writing. Some of this work employed infrared technology — previously used for satellite imaging — to detect previously unknown material by Euripides in fragments of the Oxyrhynchus papyri, a collection of ancient manuscripts held by the university. Euripides focused on the realism of his characters; for example, Euripides’ Medea is a realistic woman with recognizable emotions and is not simply a villain. In Hippolytus,

Euripides writes in a particularly modern style, demonstrating how

neither language nor sight aids in understanding in a civilization on

its last leg. Euripides makes his point about vision both through the

plot (Phaedra makes repeated references to her inability to see clearly

and her wish to have her eyes covered), and through the sparseness of

his staging, which lacked the dazzling elements that other plays often

had. The same was true of his commentary on the use of language. The

misuse of words played an important role in the storyline (Phaedra's

letter, the nurse's betrayal of Phaedra's secret, Hippolytus' refusal

to break his oath to save his own life, and his refusal to pay

lip-service to Aphrodite), but in addition, the actual language of the

play was often purposefully verbose and ungainly, again to show the

ineffectual nature of language in comprehension in Euripides' age. According to Aristotle, Euripides's contemporary Sophocles said that he portrayed men as they ought to be, and Euripides portrayed them as they were. Euripides' realistic characterizations were sometimes at the expense of a realistic plot; Among the three extant ancient Greek tragedians, Euripides is particularly known for employing the literary device known as deus ex machina,

whereby a god or goddess abruptly appears at drama's end to provide a

contrived solution to an intractable problem. In the opinion of Aristotle, writing his Poetics a

century later, this is an inadequate way to end a play. Many

classicists cite this as a reason why Euripides was less popular in his

own time.