<Back to Index>

- Physician William Harvey, 1578

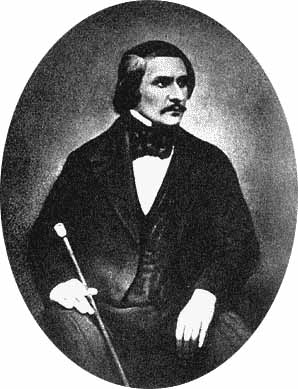

- Novelist Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol, 1809

- Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV, 1282

PAGE SPONSOR

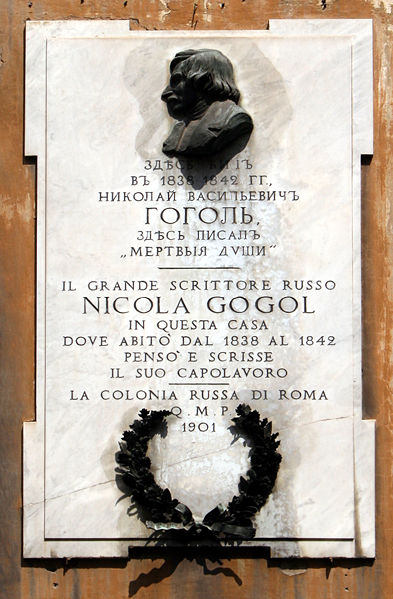

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol (Russian: Николай Васильевич Гоголь; Ukrainian:Микола Васильович Гоголь) (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1809, – 4 March [O.S. 21 February] 1852) was a Ukrainian-born Russian novelist, humourist, and dramatist.

He is considered the father of modern Russian realism. His early works, such as Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, were heavily influenced by his Ukrainian upbringing and identity. His

more mature writing satirised the corrupt bureaucracy of the Russian

Empire, leading to his exile. On his return, he immersed himself in the

Orthodox Church. The novels Taras Bul'ba (1835; 1842 [revised edition]) and Dead Souls (1842), the play The Inspector-General (1836, 1842), and the short stories Diary of a Madman, The Nose and The Overcoat (1842)

are among his best known works. With their scrupulous and scathing

realism, ethical criticism as well as philosophical depth, they remain

some of the most important works of world literature. Gogol was born in the Ukrainian Cossack village of Sorochyntsi, in Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire, present-day Ukraine. His mother was a descendant of Polish nobility.

His father Vasily Gogol-Yanovsky, a descendant of Ukrainian Cossacks,

belonged to the petty gentry, wrote poetry in Russian and Ukrainian,

and was an amateur Ukrainian language playwright who died when Gogol

was 15 years old. As was typical of the left-bank Ukrainian gentry of

the early nineteenth century, the family spoke Russian as well as

Ukrainian. As a child, Gogol helped stage Ukrainian language plays in

his uncle's home theater. In 1820 Gogol went to a school of higher art in Nizhyn and

remained there until 1828. It was there that he began writing. He was

not very popular among his schoolmates, who called him their

"mysterious dwarf", but with two or three of them he formed lasting

friendships. Very early he developed a dark and secretive disposition,

marked by a painful self-consciousness and boundless ambition. Equally

early he developed an extraordinary talent for mimicry which later on

made him a matchless reader of his own works and induced him to toy

with the idea of becoming an actor. In

1828, on leaving school, Gogol came to Petersburg, full of vague but

glowingly ambitious hopes. He had hoped for literary fame and brought with him a Romantic poem of German idyllic life — Ganz Küchelgarten.

He had it published, at his own expense, under the name of "V. Alov."

The magazines he sent it to almost universally derided it. He bought

all the copies and destroyed them, swearing never to write poetry again. Gogol was one of the first masters of the short story, alongside Alexander Pushkin, Prosper Mérimée, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. He was in touch with the "literary aristocracy", had a story published in Anton Delvig's Northern Flowers, was taken up by Vasily Zhukovsky and Pyotr Pletnyov, and (in 1831) was introduced to Pushkin. In 1831, he brought out the first volume of his Ukrainian stories (Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka), which met with immediate success. He followed it in 1832 with a second volume, and in 1835 by two volumes of stories entitled Mirgorod, as well as by two volumes of miscellaneous prose entitled Arabesques. At this time, contemporary Russian editors and critics such as Nikolai Polevoy and Nikolai Nadezhdin saw

in Gogol the emergence of a Ukrainian, rather than Russian, writer,

using his works to illustrate the differences between Russian and

Ukrainian national characters, a fact that has been overlooked in later

Russian literary history. At this time, Gogol developed a passion for Ukrainian history and tried to obtain an appointment to the history department at Kiev University. Despite the support of Pushkin and Sergey Uvarov, the Russian minister of education, his appointment was blocked by a Kievan bureaucrat on the grounds that he was unqualified. His fictional story Taras Bulba, based on the history of Ukrainian cossacks,

was the result of this phase in his interests. During this time he also

developed a close and life-long friendship with another Ukrainian then

living in Russia, the historian and naturalist Mykhaylo Maksymovych. In 1834 Gogol was made Professor of Medieval History at the University of St. Petersburg,

a job for which "he had no qualifications. He turned in a performance

ludicrous enough to warrant satiric treatment in one of his own

stories. After an introductory lecture made up of brilliant generalizations which the 'historian' had prudently prepared and

memorized, he gave up all pretense at erudition and teaching, missed two lectures out of three, and when he did appear, muttered

unintelligibly through his teeth. At the final examination, he sat in

utter silence with a black handkerchief wrapped around his head,

simulating a toothache, while another professor interrogated the

students." This academic venture proved a failure and he resigned his chair in 1835. Between

1832 and 1836 Gogol worked with great energy, and though almost all his

work has in one way or another its sources in these four years of

contact with Pushkin, he had not yet decided that his ambitions were to

be fulfilled by success in literature. During this time, the Russian

critics Stepan Shevyrev and Vissarion Belinsky, contradicting earlier critics, reclassified Gogol from a Ukrainian to a Russian writer. It was only after the presentation, on April 19, 1836, of his comedy The Government Inspector (Revizor) that he finally came to believe in his literary vocation. The comedy, a violent satire of Russian provincial bureaucracy, was able to be staged thanks only to the personal intervention of Nicholas I. From

1836 to 1848 he lived abroad, travelling throughout Germany and

Switzerland. Gogol spent the winter of 1836 - 1837 in Paris, where he spent time among Russian expatriates and Polish exiles, frequently meeting with the Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Bohdan Zaleski. He eventually settled in Rome. According to Simon Karlinsky (a professor emeritus of Slavic languages and literature at UC Berkeley) Gogol fell in love there with the nobleman Iosif Vielhorsky and started

a romantic relationship with him; this is the only documented love

affair in his life. Pushkin's

death produced a strong impression on Gogol. His principal work during

the years following Pushkin's death was the satirical epic Dead Souls. Concurrently, he worked at other tasks — recast Taras Bulba and The Portrait, completed his second comedy, Marriage (Zhenitba), wrote the fragment Rome and his most famous short story, The Overcoat. In 1841 the first part of Dead Souls was ready, and Gogol took it to Russia to supervise its printing. It appeared in Moscow in 1842, under the title, imposed by the censorship, of The Adventures of Chichikov. The book instantly established his reputation as the greatest prose writer in the language. After the triumph of Dead Souls,

Gogol came to be regarded by his contemporaries as a great satirist who

lampooned the unseemly sides of Imperial Russia. Little did they know

that Dead Souls was but the first part of a modern-day counterpart to The Divine Comedy. The first part represented the Inferno;

the second part was to depict the gradual purification and

transformation of the rogue Chichikov under the influence of virtuous

publicans and governors — Purgatory. From Palestine he

returned to Russia and passed his last years in restless movement

throughout the country. While visiting the capitals, he stayed with

various friends such as Mikhail Pogodin and Sergei Aksakov.

During this period of his life he also spent much time with his old

Ukrainian friends, Maksymovych and Osyp Bodiansky. More importantly, he

intensified his relationship with a church elder,

Matvey Konstantinovsky, whom he had known for several years.

Konstantinovsky seems to have strengthened in Gogol the fear of

perdition by insisting on the sinfulness of all his imaginative work.

His health was undermined by exaggerated ascetic practices and he fell

into a state of deep depression. On the night of February 24, 1852, he burned some of his manuscripts, which contained most of the second part of Dead Souls. He explained this as a mistake, a practical joke played on him by the Devil. Soon thereafter he took to bed, refused all food, and died in great pain nine days later. Gogol was buried at the Danilov Monastery, close to his fellow Slavophile Aleksey Khomyakov. In 1931, Moscow authorities decided to demolish the monastery and had his remains transferred to the Novodevichy Cemetery. His

body was discovered lying face down, which gave rise to the story that

Gogol had been buried alive. A Soviet critic even cut a part of his

jacket to use as a binding for his copy of Dead Souls. A piece of rock which used to stand on his grave at the Danilov was reused for the tomb of Gogol's admirer Mikhail Bulgakov. The first Gogol monument in Moscow was a Symbolist statue on Arbat Square, which represented the sculptor Nikolay Andreyev's idea of Gogol, rather than the real man. Unveiled in 1909, the statue was praised by Ilya Repin and Leo Tolstoy as an outstanding projection of Gogol's tortured personality. Stalin did not like it, however; and the statue was replaced by a more orthodox Socialist Realism monument

in 1952. It took enormous efforts to save Andreyev's original work from

destruction; it now stands in front of the house where Gogol died.