<Back to Index>

- Naturalist Michel Adanson, 1727

- Composer Domenico Carlo Maria Dragonetti, 1763

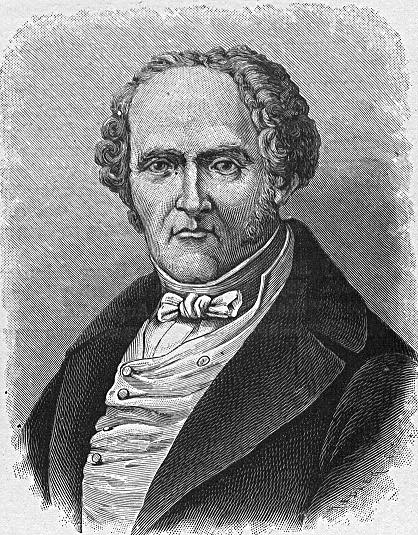

- Utopian Socialist François Marie Charles Fourier, 1772

PAGE SPONSOR

François Marie Charles Fourier (7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French utopian socialist and philosopher. Fourier is credited by modern scholars with having originated the word féminisme in 1837; as early as 1808, he had argued, in the Theory of the Four Movements, that the extension of the liberty of women was the general principle of all social progress, though he disdained any attachment to a discourse of 'equal rights'. Fourier inspired the founding of the communist community called La Reunion near present-day Dallas, Texas, as well as several other communities within the United States of America, such as the North American Phalanx in New Jersey and Community Place and five others in New York State.

Fourier was born in Besançon on April 7, 1772. Born a son of a small businessman, Fourier was more interested in architecture than he was in his father's trade. In fact, he wanted to become an engineer, but since the local Military Engineering School only accepted sons of noblemen, he was automatically ineligible for it. Fourier later was grateful that he did not pursue engineering, for he stated that it would have consumed too much of his time and taken away from his true desire to help humanity. In July 1781 after his father’s death, Fourier received two-fifths of his father’s estate, valued at more than 200,000 francs. This sudden wealth enabled Fourier the freedom to travel throughout Europe at his leisure. In 1791 he moved from Besançon to Lyon, where he was employed by the merchant M. Bousqnet. Fourier's travels also brought him to Paris where he worked as the head of the Office of Statistics for a few months. Fourier was not satisfied with making journeys on behalf of others for their commercial benefit. Having a desire to seek knowledge in everything he could, Fourier often would change business firms as well as residences in order to explore and experience new things. From 1791 to 1816 Fourier was employed in the cities of Paris, Rouen, Lyon, Marseille, and Bordeaux. As a traveling salesman and correspondence clerk, his research and thought was time-limited: he complained of "serving the knavery of merchants" and the stupefaction of "deceitful and degrading duties". A modest legacy set him up as a writer. He had three main sources for his thought: people he had met as a traveling salesman, newspapers, and introspection. His first book was published in 1808.

In April 1834, Fourier moved into a Paris apartment where he later died in October 1837.

On

October 11, 1837 at three o’clock in the afternoon, Fourier’s funeral

procession began from his home to the church of the Petits-Peres. The ceremony was attended

by over four hundred people from all trades and backgrounds. Fourier

declared that concern and cooperation were the secrets of social

success. He believed that a society that cooperated would see an

immense improvement in their productivity levels. Workers would be

recompensed for their labors according to their contribution. Fourier

saw such cooperation occurring in communities he called "phalanxes,"

based around structures called

Phalanstères or

"grand hotels." These

buildings were four level apartment complexes where the richest had the

uppermost apartments and the poorest enjoyed a ground floor residence.

Wealth was determined by one's job; jobs were assigned based on the

interests and desires of the individual. There were incentives: jobs

people might not enjoy doing would receive higher pay. Fourier

considered trade, which he associated with Jews, to be the "source of

all evil" and advocated that Jews be forced to perform farm work in the

phalansteries. Fourier

characterized poverty (not inequality) as the principal cause of

disorder in society, and he proposed to eradicate it by sufficiently

high wages and by a "decent minimum" for those who were not able to

work. He

believed that there were twelve common passions which resulted in 810

types of character, so the ideal phalanx would have exactly 1620

people. One day there would be six million of these, loosely ruled by a

world "omniarch",

or

(later)

a World

Congress

of Phalanxes. He had a touching concern for the sexually

rejected–jilted suitors would be led away by a corps of "fairies" who

would soon cure them of their lovesickness, and visitors could consult

the card-index of personality types for suitable partners for casual

sex. He also defended homosexuality as a personal preference for some

people. Fourier

was also a supporter of women's rights in a time period where

influences like Jean-Jacques

Rousseau were

prevalent. Fourier believed that all important jobs should be open to

women on the basis of skill and aptitude rather than closed on account

of gender. He spoke of women as individuals, not as half the human

couple. Fourier saw that “traditional” marriage could potentially hurt

women's rights as human beings and thus never married. Fourier's

concern was to liberate every human individual, man, woman, and child,

in two senses: Education and the liberation of human passion. On Education,

Fourier

felt

that "civilized" parents and teachers saw children as

little idlers. Fourier felt that this way

of thinking was wrong. He felt that children as early as age two and

three were very industrious. He listed the dominant tastes in all

children to include, but not limited to: Fourier

was deeply disturbed by the disorder of his time and wanted to

stabilize the course of events which surrounded him. Fourier saw his

fellow human beings living in a world full of strife, chaos, and

disorder. Fourier

is best remembered for his writings on a new

world

order based

on unity of action and harmonious collaboration. He is also known for

certain Utopian pronouncements, such as that the seas would lose their

salinity and turn to lemonade, and in a prescient view of climate

change, that the North

Pole would be

milder than the Mediterranean in a future phase of Perfect Harmony. The

influence of Fourier's ideas in French politics was carried forward

into the 1848

Revolution and

the Paris

Commune by

followers such as Victor

Considérant. Numerous

references to Fourierism appear in Dostoevsky's

political

novel The

Possessed first

published

in 1872. In it Fourierism is used by the revolutionary

faithful as something of an insult to their brethren and those within

the circle are quick to defend themselves from being labeled a

Fourierist. Whether this is because it is a foreign ideology or because

they believe it to be archaic is never made entirely clear. Fourier's

ideas also took root in America, with his followers starting phalanxes

throughout the country, including one of the most famous, Utopia,

Ohio. Kent

Bromley, in his preface to Peter Kropotkin's book The

Conquest

of Bread, considered Fourier to be the founder of the libertarian branch

of socialist thought, as opposed to the

authoritarian socialist ideas of Babeuf and Buonarroti. In the

mid-20th century, Fourier's influence began to rise again among writers

reappraising socialist ideas outside the Marxist

mainstream. After

the Surrealists had broken with the French

Communist

Party, André

Breton returned

to

Fourier, writing Ode

à Charles Fourier in

1947.

Walter

Benjamin considered

Fourier

crucial enough to devote an entire "konvolut"

of

his

massive, projected book on the Paris arcades, the Passagenwerk,

to

Fourier's

thought and influence. He writes: "To have instituted play

as the canon of a labor no longer rooted in exploitation is one of the

great merits of Fourier," and notes that "Only in the summery middle of

the nineteenth century, only under its sun, can one conceive of

Fourier's fantasy materialized." In 1969,

the Situationists quoted and adapted Fourier's Avis aux

civilisés relativement à la prochaine métamorphose

sociale in their

text Avis aux civilisés relativement à l'autogestion

généralisée. Fourier's

work has significantly influenced the writings of Gustav

Wyneken, Guy

Davenport (in

his

work of fiction Apples

and

Pears), Peter

Lamborn

Wilson, and Paul

Goodman.

In Whit

Stillman's film Metropolitan,

idealist

Tom

describes himself as a Fourierist, and debates the success

of social experiment Brook Farm with another

of the characters. David

Harvey, in the appendix to his book Spaces of Hope,

offers a personal utopian vision of the future much like Fourier's

ideas.