<Back to Index>

- Neurosurgeon Harvey Williams Cushing, 1869

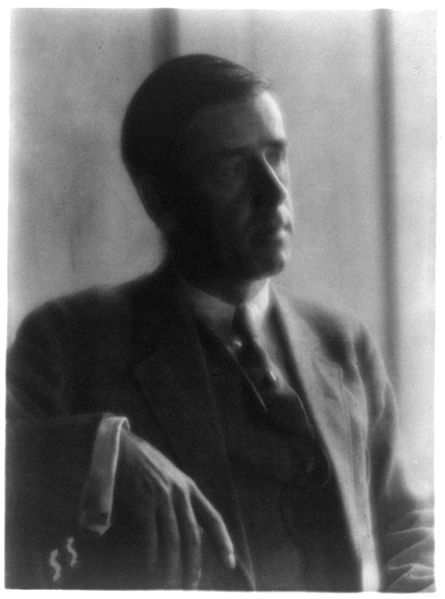

- Photographer Clarence Hudson White, 1871

- King of Spain Philip IV, 1605

PAGE SPONSOR

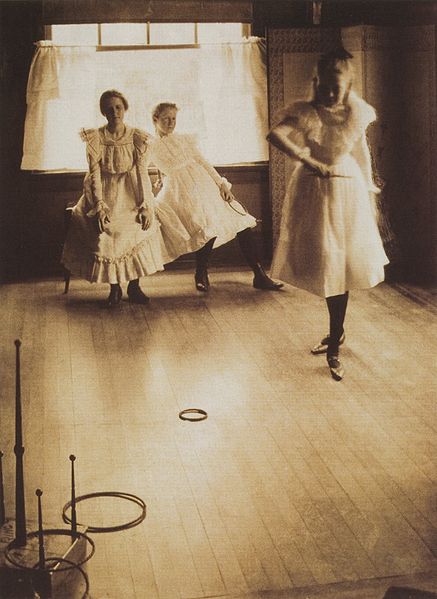

Clarence Hudson White (April 8, 1871 – July 7, 1925) was an American photographer and a founding member of the Photo-Secession movement. During his lifetime he was widely recognized as a master of the art form for his consummate sentimental, pictorial portraits and for his excellence as a teacher of photography. Toward the end of his career he founded the Clarence H. White School of Photography, which produced many of the best-known photographers of the Twentieth century including Margaret Bourke-White, Ralph Steiner, Dorothea Lange, and Paul Outerbridge.

White was born in 1871 in West Carlisle, Ohio. He moved with his family to Newark, Ohio, when he was sixteen. He was avid amateur young artist, and filled sketchbooks with his drawings and paintings before taking up photography in his late teens or early twenties. His father was a salesman for Fleek and Neal, a wholesale grocery, and after high school White joined the same firm as an accountant. In 1893 White married Jane Felix, who became White's business manager, critic, and inspiration.

White

produced many of his most famous images between 1893 and 1906, while he

was still in Ohio, despite holding a full-time job unrelated to

photography and only being able to afford two plates a week. Most of his

photographs from this period depicted relatives and friends, carefully

posed in their homes. He enjoyed collaborating with other photographers

and seeing their work, and in 1898 White founded the Newark

Camera

Club, an association for the

town's enthusiasts, prefiguring

his role as a teacher and mentor. While

in

Newark, White's photographs gradually became nationally recognized,

first winning a gold medal from the Ohio Photographer's Association in

1896 and then participating in the Philadelphia Photographic Salon exhibition in 1898. That year, on a

trip east, White met Alfred

Stieglitz, photography's most prominent figure of the time, who

praised his work. Stieglitz, White, and several other pictorial

photographers co-founded the Photo-Secession, an elite group dedicated

to furthering photography as an art

form. As

White's artistic renown spread, it became increasingly difficult for

him to balance his amateur photography with his accounting career. In

1906 he decided to quit his job, move to New

York

City, and devote his full

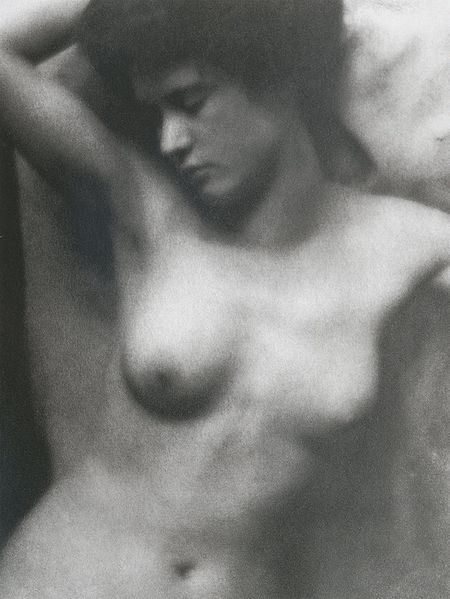

attention to photography. Stieglitz included White's photos in

exhibitions at his Photo-Secession

gallery and

published them in his highly acclaimed magazine, Camera

Work. Stieglitz devoted

an entire issue of Camera Work to White's photography and

the two men were jointly credited on several images, most notably The

Torso.

In

1907, Arthur

Wesley

Dow hired

White to teach photography at Columbia

University. He quickly became a renowned instructor, encouraging

and inspiring his students rather than formally expounding on technical

or aesthetic principles of photography.

Although White's teaching never provided him with a significant amount

of money, it enabled him to work as a full-time photographer and he

deeply loved to teach. In

1914, he founded the

Clarence H. White School of Modern Photography. Charles

J.

Martin, a former student of White's at Columbia, became one of

the first instructors at the White School. White

taught many students who went on to become notable photographers,

including Margaret

Bourke-White, Anne

Brigman, Dorothea Lange, Paul

Outerbridge, Karl

Struss, and Doris

Ulmann.

White,

Stieglitz,

and the other Photo-Secessionists initially imitated

traditional fine

arts in order to

elevate photography to high art. Referred to as pictorialists,

they

used

camera and printing techniques to emulate etchings and

achieve soft focus. However, in 1910 Stieglitz renounced pictorialism

in favor of sharply focused "straight"

photographs,

emphasizing

the camera's optical clarity and precision. White did not follow

Stieglitz's initiative, and after their separation White emerged as the

leader of pictorialist photography. In 1916 White co-founded the Pictorial

Photographers

of America (PPA),

a

national organization dedicated to promoting pictorial photography. Like the Photo-Secession,

the PPA sponsored exhibitions and published a journal. But unlike the

Photo-Secession, the PPA consciously refrained from exclusivity and

advocated using pictorial photography as a medium for art education.

White served as the association's first president until 1921. White's

photographs are black-and-white,

romanticized, pictorialist images. Women and children

were favorite subjects, and White was praised for capturing the

character of his models. White composed his images carefully, often

taking hours to pose models and frame the photograph. White also

experimented with darkroom techniques including platinum and gum

bichromate prints. During his lifetime,

White's images were widely acclaimed as the pinnacle of the art form.