<Back to Index>

- Psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe, 1915

- Sculptor Daniel Chester French, 1850

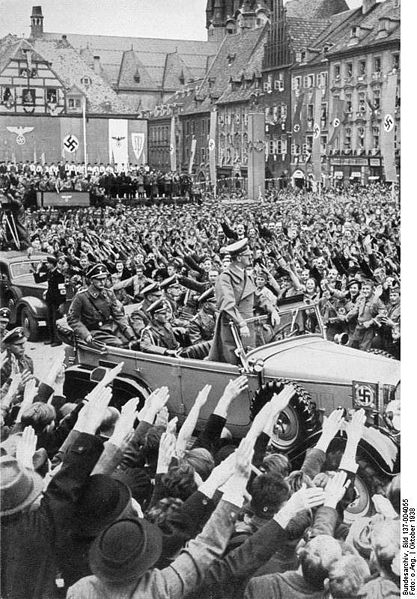

- Chancellor of Germany Adolf Hitler, 1889

PAGE SPONSOR

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party (German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945 and, after 1934, also head of state as Führer und Reichskanzler, ruling the country as an absolute dictator of Germany.

A

decorated veteran of World

War

I, Hitler joined the precursor of the Nazi Party (DAP)

in

1919 and became leader of NSDAP in 1921. He attempted a failed coup

called the Beer

Hall

Putsch in Munich in 1923, for which he was

imprisoned. Following his imprisonment, in which he wrote his book, Mein

Kampf, he gained support by promoting German

nationalism, anti-semitism, anti-capitalism,

and anti-communism with charismatic oratory and propaganda.

He

was appointed chancellor in 1933, and quickly transformed the Weimar

Republic into the Third Reich, a single-party dictatorship based on the totalitarian and autocratic ideals of national

socialism. Hitler

ultimately wanted to establish a New

Order of absolute

Nazi German hegemony in Europe. To achieve this,

he pursued a foreign

policy with the

declared goal of seizing Lebensraum ("living space") for the Aryan

people; directing the resources of the state towards this goal.

This included the rearmament of Germany, which culminated in 1939 when

the Wehrmacht invaded

Poland. In response, the United

Kingdom and France declared war against

Germany, leading to the outbreak of World

War

II in

Europe. Within

three years, Germany and the Axis

powers had occupied

most of Europe, and most of Northern

Africa, East and Southeast

Asia and the

Pacific Ocean. However, with the reversal of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet

Union, the Allies gained

the upper hand from

1942 onwards. By 1945, Allied armies had invaded German-held Europe

from all sides. Nazi forces engaged in numerous violent acts during the

war, including the systematic murder of as many as 17 million civilians, an estimated six million of

whom were Jews targeted in the

Holocaust and

between 500,000 and 1,500,000 were Romanis. Others targeted included ethnic

Poles, Soviet

civilians, Soviet

prisoners

of war, people

with

disabilities, homosexuals, Jehovah's

Witnesses, and other political

and

religious opponents. In the

final days of the war, during the Battle

of

Berlin in 1945,

Hitler married his long-time mistress Eva

Braun and, to avoid

capture by Soviet forces less than two days later, the two committed

suicide on 30 April 1945. Hitler's

father, Alois

Hitler, was an illegitimate child of Maria

Anna

Schicklgruber so

his paternity was not listed on his birth certificate and he bore his

mother's surname. In 1842, Johann

Georg

Hiedler married

Maria and in 1876 Alois testified before a notary and three witnesses

that Johann was his father. At age 39, Alois took the

surname Hitler. This surname was variously spelled Hiedler, Hüttler, Huettler and Hitler, and was

probably regularized to Hitler by a clerk. The origin of

the name is either "one who lives in a hut" (Standard

German Hütte),

"shepherd"

(Standard German hüten "to guard", English heed), or is from the Slavic word Hidlar and Hidlarcek.

(Regarding the first two theories: some German dialects make little or no

distinction between the ü-sound

and

the i-sound.) Despite

this testimony, Alois' paternity has been the subject of controversy.

After receiving a "blackmail letter" from Hitler's nephew William Patrick

Hitler threatening

to reveal embarrassing information about Hitler's family tree, Nazi

Party lawyer Hans

Frank investigated,

and, in his memoirs, claimed to have uncovered letters revealing that

Alois' mother, Maria

Schicklgruber, was employed as a housekeeper for a Jewish family in Graz and that the family's

19-year-old son, Leopold

Frankenberger, fathered Alois. No evidence has ever been

produced to support Frank's claim, and Frank himself said Hitler's full

Aryan blood was obvious. Frank's claims were widely

believed in the 1950s, but by the 1990s, were generally doubted by

historians. Ian

Kershaw dismisses the Frankenberger story as a "smear" by Hitler's

enemies, noting that all Jews had been expelled from Graz in the 15th

century and were not allowed to return until well after Alois was born.

Adolf

Hitler

was born on 20 April 1889 at half-past six in the evening at the

Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in Braunau

am

Inn, Austria–Hungary, the

fourth of Alois and Klara

Hitler's six children. At the

age of three, his family moved to Kapuzinerstrasse 5 in Passau,

Germany, where the young Hitler would acquire Lower

Bavarian rather

than Austrian as his lifelong native dialect. In 1894, the family moved to Leonding near Linz,

then

in June 1895, Alois retired to a small landholding at Hafeld near Lambach,

where

he tried his hand at farming and beekeeping. During this time,

the young Hitler attended school in nearby Fischlham. As a child, he

tirelessly played "Cowboys

and

Indians" and, by his own account, became fixated on war after

finding a picture book about the Franco-Prussian

War in his father's

things. He wrote in Mein

Kampf: "It was not long before the great historic struggle had

become my greatest spiritual experience. From then on, I became more

and more enthusiastic about everything that was in any way connected

with war or, for that matter, with soldiering." His

father's efforts at Hafeld ended in failure and the family moved to

Lambach in 1897. There, Hitler attended a Catholic school located in an 11th-century Benedictine cloister whose walls were

engraved in a number of places with crests containing the symbol of the swastika. It was in Lambach that the

eight year-old Hitler sang in the church choir, took singing lessons,

and even entertained the fantasy of one day becoming a priest. In 1898, the family

returned permanently to Leonding.

His

younger brother Edmund died of measles on 2 February 1900, causing

permanent changes in Hitler. He went from a confident, outgoing boy who

found school easy, to a morose, detached, sullen boy who constantly

battled his father and his teachers. Hitler

was close to his mother, but had a troubled relationship with his authoritarian father, who frequently beat

him, especially in the years after Alois' retirement and disappointing

farming efforts. Alois wanted his son to

follow in his footsteps as an Austrian customs official, and this

became a huge source of conflict between them. Despite his son's pleas to

go to classical high school and become an artist, his father sent him

to the Realschule in Linz, a technical high school of about 300

students, in September 1900. Hitler rebelled, and in Mein

Kampf confessed

to failing his first year in hopes that once his father saw "what

little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me

devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." But Alois never relented

and Hitler became even more bitter and rebellious. For young

Hitler, German

Nationalism quickly

became an obsession, and a way to rebel against his father, who proudly

served the Austrian government. Most people who lived along the German-Austrian border

considered themselves German-Austrians, but Hitler expressed loyalty

only to Germany. In defiance of the Austrian monarchy, and his father

who continually expressed loyalty to it, Hitler and his young friends

liked to use the German greeting "Heil", and sing the German

anthem "Deutschland

Über

Alles" instead of the Austrian

Imperial anthem. After

Alois' sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's behaviour at the

technical school became even more disruptive, and he was asked to

leave. He enrolled at the Realschule in Steyr in 1904, but upon

completing his second year, he and his friends went out for a night of

celebration and drinking, and an intoxicated Hitler tore his school

certificate into four pieces and used it as toilet paper. When someone

turned the stained certificate in to the school's director, he "...

gave him such a dressing-down that the boy was reduced to shivering

jelly. It was probably the most painful and humiliating experience of

his life." Hitler was expelled, never

to return to school again. At age

15, Hitler took part in his First

Holy

Communion on Whitsunday,

22

May 1904, at the Linz Cathedral. His sponsor was Emanuel

Lugert, a friend of his late father. From 1905

on, Hitler lived a bohemian life in Vienna on an orphan's pension and

support from his mother. He was rejected twice by the Academy of

Fine Arts Vienna (1907 – 1908),

citing

"unfitness for painting", and was told his abilities lay instead

in the field of architecture. His memoirs reflect a fascination with

the subject: The

purpose of my trip was to study the picture gallery in the Court

Museum, but I had eyes for scarcely anything but the Museum itself.

From morning until late at night, I ran from one object of interest to

another, but it was always the buildings which held my primary interest. Following

the school rector's recommendation, he too became convinced this was

his path to pursue, yet he lacked the proper academic preparation for

architecture school: In a

few days I myself knew that I should some day become an architect. To

be sure, it was an incredibly hard road; for the studies I had

neglected out of spite at the Realschule were sorely needed. One could

not attend the Academy's architectural school without having attended

the building school at the Technic, and the latter required a

high-school degree. I had none of all this. The fulfilment of my

artistic dream seemed physically impossible.

On 21

December 1907, Hitler's mother died of breast

cancer at age 47.

Ordered by a court in Linz, Hitler gave his share of the orphans'

benefits to his sister Paula. When he was 21, he inherited money from

an aunt. He struggled as a painter in Vienna, copying scenes from

postcards and selling his paintings to merchants and tourists. After

being rejected a second time by the Academy of Arts, Hitler ran out of

money. In 1909, he lived in a shelter for the homeless.

By

1910, he had settled into a house

for

poor working men on Meldemannstraße. Another resident of

the house, Reinhold

Hanisch, sold Hitler's paintings until the two men had a bitter

falling-out. Hitler

said he first became an anti-Semite in Vienna, which had a large Jewish

community, including Orthodox

Jews who had fled

the pogroms in Russia. According to

childhood friend August

Kubizek, however, Hitler was a "confirmed anti-Semite" before he

left Linz. Vienna at that time was a

hotbed of traditional religious prejudice and 19th century racism.

Hitler

may have been influenced by the writings of the ideologist and

anti-Semite Lanz

von

Liebenfels and polemics from politicians such as Karl

Lueger, founder of the Christian

Social

Party and Mayor

of

Vienna, the composer Richard

Wagner, and Georg

Ritter

von Schönerer, leader of the pan-Germanic Away from Rome! movement. Hitler claims in Mein Kampf that his

transition from opposing antisemitism on religious grounds to

supporting it on racial grounds came from having seen an Orthodox

Jew. There

were very few Jews in Linz. In the course of centuries the Jews who

lived there had become Europeanised in external appearance and

were so much like other human beings that I even looked upon them as

Germans. The reason why I did not then perceive the absurdity of such

an illusion was that the only external mark which I recognized as

distinguishing them from us was the practice of their strange religion.

As I thought that they were persecuted on account of their faith my

aversion to hearing remarks against them grew almost into a feeling of

abhorrence. I did not in the least suspect that there could be such a

thing as a systematic antisemitism. Once, when passing through the

inner City, I suddenly encountered a phenomenon in a long caftan and

wearing black side-locks. My first thought was: Is this a Jew? They

certainly did not have this appearance in Linz. I carefully watched the

man stealthily and cautiously but the longer I gazed at the strange

countenance and examined it feature by feature, the more the question

shaped itself in my brain: Is this a German? If

this

account is true, Hitler apparently did not act on his new belief. He

often was a guest for dinner in a noble Jewish house, and he interacted

well with Jewish merchants who tried to sell his paintings. Hitler

may also have been influenced by Martin

Luther's On

the

Jews and their Lies. In Mein

Kampf, Hitler refers to Martin Luther as a great warrior, a true

statesman, and a great reformer, alongside Richard

Wagner and Frederick

the

Great. Wilhelm

Röpke, writing after the Holocaust, concluded that "without

any question, Lutheranism influenced the political,

spiritual and social history of Germany in a way that, after careful

consideration of everything, can be described only as fateful." Hitler

claimed that Jews were enemies of the Aryan

race. He held them responsible for Austria's crisis. He also

identified certain forms of socialism and Bolshevism,

which

had many Jewish leaders, as Jewish movements, merging his

antisemitism with anti-Marxism.

Later,

blaming Germany's military defeat in World War I on the 1918

revolutions, he considered Jews the culprits of Imperial Germany's

downfall and subsequent economic problems as well. Generalising

from

tumultuous scenes in the parliament of the multi-national Austrian

monarchy, he decided that the democratic parliamentary system was

unworkable. However, according to August Kubizek, his one-time

roommate, he was more interested in Wagner's operas than in his

politics. Hitler

received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to Munich.

He

wrote in Mein

Kampf that he had

always longed to live in a "real" German city. In Munich, he became

more interested in architecture and, he says, the writings of Houston

Stewart

Chamberlain. Moving to Munich also helped him escape military

service in Austria

for a time, but the Munich police (acting in cooperation with the

Austrian authorities) eventually arrested him. After a physical exam

and a contrite plea, he was deemed unfit for service and allowed to

return to Munich. However, when Germany entered World War I in August

1914, he petitioned King Ludwig

III

of Bavaria for

permission to serve in a Bavarian regiment. This request was

granted, and Adolf Hitler enlisted in the Bavarian army.

Hitler

served

in France and Belgium in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment

(called Regiment List after

its

first commander), ending the war as a Gefreiter (equivalent at the time to a lance

corporal in the

British and private

first

class in the

American armies). He was a runner,

"a

dangerous enough job" on the Western Front, and

was often exposed to enemy fire. He participated in a number of major

battles on the Western Front, including the First

Battle

of Ypres, the Battle

of

the Somme, the Battle

of

Arras and the Battle

of

Passchendaele. The Battle of Ypres

(October 1914), which became known in Germany as the Kindermord bei Ypern (Massacre of the Innocents)

saw approximately 40,000 men (between a third and a half) of the nine

infantry divisions present killed in 20 days, and Hitler's own company

of 250 reduced to 42 by December. Biographer John

Keegan has said

that this experience drove Hitler to become aloof and withdrawn for the

remaining years of war. Hitler

was twice decorated for bravery. He received the Iron

Cross, Second Class, in 1914 and Iron Cross, First Class, in 1918,

an honour rarely given to a Gefreiter. However,

because

the regimental staff thought Hitler lacked leadership skills,

he was never promoted to Unteroffizier (equivalent to a British

corporal). Other historians say

that

the reason he was not promoted is that he was not a German

citizen. His duties at regimental headquarters, while often dangerous,

gave Hitler time to pursue his artwork. He drew cartoons and

instructional drawings for an army newspaper. In 1916, he was wounded

in either the groin area or the left thigh during the Battle of the

Somme, but returned to the front in March 1917. He received the Wound

Badge later that

year. A noted German historian and author, Sebastian Haffner, referring to Hitler's experience at the front, suggests he

did have at least some understanding of the military. On 15

October 1918, Hitler was admitted to a field

hospital, temporarily blinded by a mustard

gas attack. The

English psychologist David

Lewis and Bernhard

Horstmann suggest the blindness may have been the result of a conversion

disorder (then

known as "hysteria"). Citing

contemporary witnesses, Claus Hant concludes that the psychotic episode

led Hitler to believe that he had received a divine mission. In fact, Hitler said it was

during this experience that he became convinced the purpose of his life

was to "save Germany." Some scholars, notably Lucy

Dawidowicz, argue that an intention to

exterminate Europe's Jews was fully formed in Hitler's mind at this

time, though he probably had not thought through how it could be done.

Most historians think the decision was made in 1941, and some think it

came as late as 1942. Two

passages in Mein

Kampf mention the

use of poison

gas: Hitler

had long admired Germany, and during the war he had become a passionate

German patriot, although he did not become a German citizen until 1932.

Hitler found the war to be 'the greatest of all experiences' and

afterwards he was praised by a number of his commanding officers for

his bravery. He was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918 even while

the German army still held enemy territory. Like many other German

nationalists, Hitler believed in the Dolchstoßlegende ("dagger-stab legend")

which claimed that the army, "undefeated in the field," had been

"stabbed in the back" by civilian leaders and Marxists back on the home

front. These politicians were later dubbed the November

Criminals. The Treaty

of

Versailles deprived

Germany of various territories, demilitarised the Rhineland and imposed other

economically damaging sanctions. The treaty re-created Poland, which

even moderate Germans regarded as an outrage. The treaty also blamed

Germany for all the horrors of the war, something which major

historians such as John

Keegan now consider

at least in part to be victor's

justice: most European nations in the run-up to World War I had

become increasingly militarised and were eager to fight.

The culpability of Germany was used as a basis to impose reparations on

Germany (the amount was repeatedly revised under the Dawes

Plan, the Young

Plan, and the Hoover Moratorium).

Germany in turn perceived the treaty and especially,

Article 231 the paragraph on the German responsibility for the war, as

a

humiliation. For example, there was a nearly total demilitarisation of

the armed forces, allowing Germany only six battleships, no submarines,

no air force, an army of 100,000 without conscription and no armoured

vehicles. The treaty was an important factor in both the social and

political conditions encountered by Hitler and his Nazis as they sought

power. Hitler and his party used the signing of the treaty by the

"November Criminals" as a reason to build up Germany so that it could

never happen again. He also used the "November Criminals" as

scapegoats, although at the Paris

peace

conference, these politicians had had very little choice in

the matter. After

World War I, Hitler remained in the army and returned to Munich, where

he – in contrast to his later declarations – attended the funeral march

for the murdered Bavarian prime minister Kurt

Eisner. After the suppression of the Bavarian

Soviet

Republic, he took part in "national thinking" courses

organized by the Education

and

Propaganda Department (Dept

Ib/P)

of the Bavarian Reichswehr Group, Headquarters 4 under

Captain Karl

Mayr. Scapegoats were found in "international Jewry", communists,

and politicians across the party spectrum, especially the parties of the Weimar

Coalition. In July

1919, Hitler was appointed a Verbindungsmann (police spy) of an Aufklärungskommando (Intelligence Commando) of

the Reichswehr, both to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate a small party, the German

Workers'

Party (DAP).

During his inspection of the party, Hitler was impressed with founder Anton

Drexler's anti-semitic,

nationalist, anti-capitalist and anti-Marxist ideas, which favoured a

strong active government, a "non-Jewish" version of socialism and

mutual solidarity of all members of society. Drexler was impressed with

Hitler's oratory skills and invited him to join the party. Hitler

joined DAP on 12 September 1919 and became the party's 55th

member. He was also made the

seventh member of the executive committee. Years

later,

he claimed to be the party's seventh overall member, but it has been established that this claim is false. Here

Hitler met Dietrich

Eckart, one of the early founders of the party and member of the

occult Thule

Society. The

Thule

members believed in the coming of a “German Messiah” who would

redeem Germany after its defeat in World War I. Dietrich Eckart

expressed his anticipation in a poem he published months before he met

Hitler for the first time. In the poem, Eckart refers to ‘the Great

One’, ‘the Nameless One’, ‘Whom all can sense but no one saw’. When

Eckart met Hitler in 1919 he believed to have found the prophesied

redeemer. Eckart became Hitler's

mentor, exchanging ideas with him, teaching him how to dress and speak,

and introducing him to a wide range of people. Hitler thanked Eckart by

paying tribute to him in the second volume of Mein Kampf. To

increase the party's appeal, the party changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische

Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or National

Socialist

German Workers Party (abbreviated

NSDAP). Hitler

was discharged from the army in March 1920 and with his former

superiors' continued encouragement began participating full time in the

party's activities. By early 1921, Hitler was becoming highly effective

at speaking in front of large crowds. In February, Hitler spoke before

a crowd of nearly six thousand in Munich. To publicize the meeting, he

sent out two truckloads of party supporters to drive around with swastikas,

cause

a commotion and throw out leaflets, their first use of this

tactic. Hitler gained notoriety outside of the party for his rowdy, polemic speeches against the Treaty

of Versailles, rival politicians (including monarchists,

nationalists

and other non-internationalist socialists) and especially

against Marxists and Jews. The NSDAP was centred in Munich, a

hotbed of German nationalists who included Army officers determined to

crush Marxism and undermine the Weimar republic. Gradually they noticed

Hitler and his growing movement as a suitable vehicle for their goals.

Hitler traveled to Berlin to visit nationalist groups during the summer

of 1921, and in his absence there was a revolt among the DAP leadership

in Munich. The party

was run by an executive committee whose original members considered

Hitler to be overbearing. They formed an alliance with a group of

socialists from Augsburg.

Hitler

rushed back to Munich and countered them by tendering his

resignation from the party on 11 July 1921. When they realized the loss

of Hitler would effectively mean the end of the party, he seized the

moment and announced he would return on the condition that he replace

Drexler as party chairman, with unlimited powers. Infuriated committee

members (including Drexler) held out at first. Meanwhile an anonymous

pamphlet appeared entitled Adolf

Hitler:

Is he a traitor?, attacking Hitler's lust for power and

criticizing the violent men around him. Hitler responded to its

publication in a Munich newspaper by suing for libel and later won a

small settlement. The

executive committee of the NSDAP eventually backed down and Hitler's

demands were put to a vote of party members. Hitler received 543 votes

for and only one against. At the next gathering on 29 July 1921, Adolf

Hitler was introduced as Führer of the National Socialist

German Workers' Party, marking the first time this title was publicly

used. Hitler's

beer hall oratory, attacking Jews, social

democrats, liberals,

reactionary

monarchists, capitalists and communists, began

attracting adherents. Early followers included Rudolf

Hess, the former air force pilot Hermann

Göring, and the army captain Ernst

Röhm, who eventually became head of the Nazis' paramilitary

organization, the SA (Sturmabteilung,

or

"Storm Division"), which protected meetings and attacked political

opponents. As well, Hitler assimilated independent groups, such as the Nuremberg-based Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft, led

by Julius

Streicher, who became Gauleiter of Franconia.

Hitler

attracted the attention of local business interests, was accepted into influential circles of Munich society, and became

associated with wartime General Erich

Ludendorff during

this time. Encouraged

by

this early support, Hitler decided to use Ludendorff as a front in

an attempted coup, later known as the "Beer

Hall Putsch"

(sometimes as the "Hitler Putsch"

or

"Munich Putsch"). The Nazi Party had copied Italy's fascists in appearance and had

adopted some of their policies, and in 1923, Hitler wanted to emulate Benito

Mussolini's "March

on

Rome" by staging his own "Campaign in Berlin". Hitler and Ludendorff obtained the clandestine support of Gustav

von

Kahr, Bavaria's de

facto ruler, along

with leading figures in the Reichswehr and the police. As

political posters show, Ludendorff, Hitler and the heads of the

Bavarian police and military planned on forming a new government. On 8

November 1923, Hitler and the SA stormed a public meeting headed by

Kahr in the Bürgerbräukeller,

a

large beer hall in Munich. He declared that he had set up a new

government with Ludendorff and demanded, at gunpoint, the support of

Kahr and the local military establishment for the destruction of the

Berlin government. Kahr withdrew his support

and fled to join the opposition to Hitler at the first opportunity. The next day, when Hitler

and his followers marched from the beer hall to the Bavarian

War

Ministry to

overthrow the Bavarian government as a start to their "March on

Berlin", the police dispersed them. Sixteen

NSDAP

members were

killed. Hitler

fled to the home of Ernst

Hanfstaengl and

contemplated suicide. He was soon arrested for high

treason. Alfred

Rosenberg became temporary leader of the party. During Hitler's

trial, he was given almost unlimited time to speak, and his popularity

soared as he voiced nationalistic sentiments in his defence

speech. A Munich

personality became a nationally known figure. On 1 April 1924, Hitler

was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg

Prison. Hitler received favoured treatment from the guards and had

much fan mail from admirers. He was pardoned and released from jail on

20 December 1924, by order of the Bavarian Supreme Court on 19

December, which issued its final rejection of the state prosecutor's

objections to Hitler's early release. Including

time

on remand, he had served little more than one year of his sentence. On 28

June 1925, Hitler wrote a letter from Uffing to the editor of The

Nation in New

York City stating how long he had been in prison at "Sandberg a. S."

[sic] and how much his privileges had been revoked. While at

Landsberg he dictated most of the first volume of Mein Kampf (My Struggle,

originally entitled Four

and

a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice)

to his deputy Rudolf

Hess. The book, dedicated to

Thule Society member Dietrich

Eckart, was an autobiography and an exposition of his ideology. Mein Kampf was influenced by The

Passing

of the Great Race by Madison

Grant which Hitler

called "my Bible." It was published in two

volumes in 1925 and 1926, selling about 240,000 copies between 1925 and

1934. By the end of the war, about 10 million copies had been sold

or distributed (newlyweds and soldiers received free copies). Hitler

spent years dodging taxes on the royalties of his book and had

accumulated a tax debt of about 405,500 Reichsmarks (€6 million in today's money) by the time he became chancellor (at which time his debt was

waived). The copyright of Mein Kampf in Europe is claimed by the

Free State of Bavaria and scheduled to end on 31 December 2015.

Reproductions in Germany are authorized only for scholarly purposes and

in heavily commented form. The situation is, however, unclear.

Historian Werner Maser, in an interview with Bild

am

Sonntag has

stated that Peter Raubal, son of Hitler's nephew, Leo

Raubal, would have a strong legal case for winning the copyright

from Bavaria if he pursued it. Raubal has stated he wants no part of

the rights to the book, which could be worth millions of euros. The uncertain status has

led to contested trials in Poland and Sweden. Mein Kampf, however,

is published in the U.S., as well as in other countries such as Turkey and Israel,

by

publishers with various political positions.

At the

time of Hitler's release, the political situation in Germany had calmed

and the economy had improved, which hampered Hitler's opportunities for

agitation. Though the "Hitler Putsch"

had

given Hitler some national prominence, his party's mainstay was

still Munich. The NSDAP

and its organs were banned in Bavaria after the collapse of the putsch.

Hitler convinced Heinrich

Held, Prime Minister of Bavaria, to lift the ban, based on

representations that the party would now only seek political power

through legal means. Even though the ban on the NSDAP was removed

effective 16 February 1925, Hitler incurred a new ban

on public speaking as a result of an inflammatory speech. Since Hitler

was banned from public speeches, he appointed Gregor

Strasser, who in 1924 had been elected to the Reichstag,

as Reichsorganisationsleiter, authorizing him to organize the

party in northern Germany. Strasser, joined by his younger brother Otto and Joseph Goebbels, steered an increasingly independent course, emphasizing

the socialist element in the party's programme. The Arbeitsgemeinschaft der

Gauleiter Nord-West became

an

internal opposition, threatening Hitler's authority, but this

faction was defeated at the Bamberg

Conference in 1926,

during which Goebbels joined Hitler. After

this encounter, Hitler centralized the party even more and asserted the Führerprinzip ("Leader

principle")

as the basic principle of party organization. Leaders were

not elected by their group but were rather appointed by their superior

and were answerable to them while demanding unquestioning obedience

from their inferiors. Consistent with Hitler's disdain for democracy,

all power and authority devolved from the top down. A key

element of Hitler's appeal was his ability to evoke a sense of offended

national pride caused by the Treaty of Versailles imposed on the defeated German

Empire by the

Western Allies. Germany had lost economically important territory in

Europe along with its colonies and in admitting to sole responsibility

for the war had agreed to pay a huge reparations bill totaling

132 billion marks.

Most

Germans bitterly resented these terms, but early Nazi attempts to

gain support by blaming these humiliations on "international Jewry"

were not particularly successful with the electorate. The party learned

quickly, and soon a more subtle propaganda emerged, combining

antisemitism with an attack on the failures of the "Weimar system" and

the parties supporting it. Having

failed in overthrowing the Republic by a coup, Hitler pursued a

"strategy of legality": this meant formally adhering to the rules of

the Weimar Republic until he had legally gained power. He would then

use the institutions of the Weimar Republic to destroy it and establish

himself as dictator. Some party members, especially in the paramilitary

SA, opposed this strategy; Röhm and others ridiculed Hitler as "Adolphe Legalité". The

political turning point for Hitler came when the Great

Depression hit

Germany in 1930. The Weimar Republic had never been firmly rooted and

was openly opposed by right-wing conservatives (including monarchists),

communists and the Nazis. As the parties loyal to the democratic, parliamentary

republic found

themselves unable to agree on counter-measures, their grand

coalition broke up

and was replaced by a minority cabinet. The new Chancellor, Heinrich

Brüning of the

Roman Catholic Centre

Party, lacking a majority in parliament, had to implement his

measures through the president's emergency

decrees. Tolerated by the majority of parties, this rule by decree

would become the norm over a series of unworkable parliaments and paved

the way for authoritarian forms of government. The Reichstag's initial opposition to

Brüning's measures led to premature elections in September 1930.

The republican parties lost their majority and their ability to resume

the grand coalition, while the Nazis suddenly rose from relative

obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote along with 107 seats. In the

process, they jumped from the ninth-smallest party in the chamber to

the second largest. In

September–October 1930, Hitler appeared as a major defence witness at

the trial in Leipzig of two junior Reichswehr officers charged with membership of the Nazi Party, which at that time was forbidden to Reichswehr personnel. The two officers, Leutnants Richard Scheringer and Hans

Ludin, admitted quite openly to Nazi Party membership, and used as

their defence that the Nazi Party membership should not be forbidden to

those serving in the Reichswehr. When the Prosecution argued

that the Nazi Party was a dangerous revolutionary force, one of the

defence lawyers, Hans

Frank, had Hitler

brought to the stand to prove that the Nazi Party was a law-abiding

party. During his testimony,

Hitler insisted that his party was determined to come to power legally,

that the phrase "National Revolution" was only to be interpreted

"politically", and that his Party was a friend, not an enemy of the Reichswehr. Hitler's testimony of 25

September 1930 won him many admirers within the ranks of the officer

corps. Brüning's

measures

of budget consolidation and financial austerity brought little economic

improvement and were extremely unpopular. Under these circumstances,

Hitler appealed to the bulk of German farmers, war veterans and the

middle class, who had been hard-hit by both the inflation of the 1920s

and the unemployment of the Depression. In September 1931, Hitler's

niece Geli

Raubal was found

dead in her bedroom in his Munich apartment (his half-sister Angela and her daughter Geli had

been with him in Munich since 1929), an apparent suicide. Geli, who was

believed to be in some sort of romantic relationship with Hitler, was

19 years younger than he was and had used his gun. His niece's death is

viewed as a source of deep, lasting pain for him. In 1932,

Hitler intended to run against the aging President Paul

von

Hindenburg in

the scheduled presidential

elections. His 27 January 1932 speech to the Industry Club in Düsseldorf won him, for the first

time, support from a broad swath of Germany's most powerful

industrialists. Though Hitler had left

Austria in 1913 and had renounced his Austrian citizenship in 1925, he

still had not acquired German citizenship and hence could not run for

public office. On 25 February, however, the interior minister of the Brunswick,

a

Nazi (the Nazis were part of a right-wing coalition governing the

state) appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to

the Reichsrat in Berlin. This appointment

made Hitler a citizen of Brunswick. In those days, the states

conferred citizenship, so this automatically made Hitler a citizen of

Germany as well and thus eligible to run for president. The new

German citizen ran against Hindenburg, who was supported by a broad range of nationalist,

monarchist,

Catholic, republican and even social democratic

parties. Another candidate was a Communist and member of a fringe

right-wing party. Hitler's campaign was called "Hitler über

Deutschland" (Hitler over Germany). The name had a double

meaning; besides a reference to his dictatorial ambitions, it referred

to the fact that he campaigned by aircraft. Hitler came in second on

both rounds, attaining more than 35% of the vote during the second one

in April. Although he lost to Hindenburg, the election established

Hitler as a realistic alternative in German politics.

Meanwhile,

Papen

tried to get his revenge on Schleicher by working toward the

General's downfall, through forming an intrigue with the camarilla and Alfred

Hugenberg, media mogul and chairman of the DNVP. Also involved were Hjalmar

Schacht, Fritz

Thyssen and other leading German businessmen and international

bankers. They

financially supported

the Nazi Party, which had been brought to the brink of bankruptcy by

the cost of heavy campaigning. The businessmen wrote letters to

Hindenburg, urging him to appoint Hitler as leader of a government

"independent from parliamentary parties" which could turn into a

movement that would "enrapture millions of people." Finally,

the president reluctantly agreed to appoint Hitler Chancellor of a

coalition government formed by the NSDAP and DNVP. However, the Nazis

were to be contained by a framework of conservative cabinet ministers,

most notably by Papen as Vice-Chancellor and by Hugenberg as

Minister of the Economy. The only other Nazi besides Hitler to get a

portfolio was Wilhelm

Frick, who was given the relatively powerless interior ministry (in

Germany at the time, most powers wielded by the interior minister in

other countries were held by the interior ministers of the states). As

a concession to the Nazis, Göring was named minister

without

portfolio. While Papen intended to use Hitler as a

figurehead, the Nazis gained key positions. On the

morning of 30 January 1933, in Hindenburg's office, Adolf Hitler was

sworn in as Chancellor during what some observers later described as a

brief and simple ceremony. His first

speech

as Chancellor took

place on 10 February. The Nazis' seizure of power subsequently became

known as the Machtergreifung or Machtübernahme. Having

become Chancellor, Hitler foiled all attempts by his opponents to gain

a majority in parliament. Because no single party could gain a majority, Hitler persuaded President Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag again. Elections were

scheduled for early March, but on 27 February 1933, the Reichstag building was set on fire. Since a Dutch

independent

communist was

found in the building, the fire was blamed on a communist plot. The

government reacted with the Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February which

suspended basic rights, including habeas

corpus. Under the provisions of this decree, the German

Communist

Party (KPD)

and other groups were suppressed, and Communist functionaries and

deputies were arrested, forced to flee, or murdered. Campaigning

continued,

with the Nazis making use of paramilitary violence,

anti-communist hysteria, and the government's resources for propaganda.

On election day, 6 March, the NSDAP increased its result to 43.9% of

the vote, remaining the largest party, but its victory was marred by

its failure to secure an absolute majority, necessitating maintaining a

coalition with the DNVP. On 21

March, the new Reichstag was constituted with an

opening ceremony held at Potsdam's garrison church. This "Day of

Potsdam" was staged to demonstrate reconciliation and unity between the

revolutionary Nazi movement and "Old Prussia" with its elites and

virtues. Hitler appeared in a tail coat and humbly greeted the aged

President Hindenburg. Because

of the Nazis' failure to obtain a majority on their own, Hitler's

government confronted the newly elected Reichstag with the Enabling

Act that would have

vested the cabinet with legislative powers for a period of four years.

Though such a bill was not unprecedented, this act was different since

it allowed for deviations from the constitution. Since the bill

required a ⅔ majority in order to pass, the government needed the

support of other parties. The position of the Centre Party, the third

largest party in the Reichstag,

turned

out to be decisive: under the leadership of Ludwig

Kaas, the party decided to vote for the Enabling Act. It did so in

return for the government's oral guarantees regarding the Church's liberty, the concordats

signed by German states and the continued existence of the Centre Party. On 23

March, the Reichstag assembled in a replacement

building under extremely turbulent circumstances. Some SA men served as

guards within while large groups outside the building shouted slogans

and threats toward the arriving deputies. Kaas announced that the

Centre Party would support the bill with "concerns put aside," while

Social Democrat Otto

Wels denounced the

act in his speech. At the end of the day, all parties except the Social

Democrats voted in favour of the bill. The Communists, as well as some

Social Democrats, were barred from attending. The Enabling Act,

combined with the Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed

Hitler's government into a legal dictatorship. —Adolf Hitler to a

British correspondent in Berlin, June 1934 With this

combination of legislative and executive power, Hitler's government

further suppressed the remaining political opposition.

The

Communist Party of Germany and the Social

Democratic

Party (SPD)

were banned, while all other political parties were forced to dissolve

themselves. Finally, on 14 July, the Nazi Party was declared the only

legal

party in

Germany. Hitler

used the SA paramilitary to push Hugenberg into resigning, and

proceeded to politically isolate Vice-Chancellor Papen. Because the

SA's demands for political and military power caused much anxiety among

military and political leaders, Hitler used allegations of a plot by

the SA leader Ernst

Röhm to purge

the SA's leadership during the Night

of

the Long Knives. As well, opponents unconnected with the SA were murdered, notably Gregor

Strasser and former

Chancellor Kurt

von

Schleicher. President Paul

von

Hindenburg died

on 2 August 1934. Rather than call new elections as required by the constitution,

Hitler's

cabinet passed a law proclaiming the presidency vacant and

transferred the role and powers of the head of state to Hitler as Führer

und

Reichskanzler (leader

and

chancellor). This action effectively removed the last legal remedy

by which Hitler could be dismissed – and with it, nearly all

institutional checks and balances on his power. On 19

August a plebiscite approved the merger of the presidency with the

chancellorship winning 84.6% of the electorate. This

action technically

violated both the constitution and the Enabling Act. The constitution

had been amended in 1932 to make the president of the High Court of

Justice, not the chancellor, acting president until new elections could

be held. The Enabling Act specifically barred Hitler from taking any

action that tampered with the presidency. However, no one dared object.

As head

of state, Hitler now became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. When

it came time for the soldiers and sailors to swear the traditional

loyalty oath, it had been altered into an oath of personal loyalty to

Hitler. Normally, soldiers and sailors swear loyalty to the holder of

the office of supreme commander/commander-in-chief,

not

a specific person. In 1938,

Hitler forced the resignation of his War Minister (formerly Defense

Minister), Werner

von

Blomberg, after evidence surfaced that Blomberg's new wife had

a criminal past. Prior to removing Blomberg, Hitler and his clique

removed army commander Werner

von

Fritsch on suspicion of homosexuality. Hitler replaced the

Ministry of War with the Oberkommando

der

Wehrmacht (High

Command of the Armed Forces, or OKW), headed by the pliant General Wilhelm

Keitel. More importantly, Hitler announced he was assuming personal

command of the armed forces. He took over Blomberg's other old post,

that of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, for himself. He was

already Supreme Commander by virtue of holding the powers of the

president. The next day, the newspapers announced, "Strongest

concentration of powers in Führer's hands!"

Having

secured

supreme political power, Hitler went on to gain public support

by convincing most Germans he was their saviour from the economic Depression, the Versailles treaty, communism, the "Judeo-Bolsheviks",

and

other "undesirable" minorities.

The

Nazis eliminated opposition through a process known as Gleichschaltung ("bringing into line").

Hitler

oversaw

one of the greatest expansions of industrial production and

civil improvement Germany had ever seen, mostly based on debt flotation

and expansion of the military. Nazi policies toward women strongly

encouraged them to stay at home to bear children and keep house. In a

September 1934 speech to the National Socialist Women's Organization,

Adolf Hitler argued that for the German woman her "world is her

husband, her family, her children, and her home." This policy was

reinforced by bestowing the Cross of Honor of the German Mother on

women bearing four or more babies. The unemployment rate was cut

substantially, mostly through arms production and sending women home so

that men could take their jobs. Given this, claims that the German

economy achieved

near full

employment are at

least partly artefacts of propaganda from the era. Much of the

financing for Hitler's reconstruction and rearmament came from currency

manipulation by Hjalmar Schacht, including the clouded credits through

the Mefo

bills. Hitler

oversaw one of the largest infrastructure-improvement campaigns in

German history, with the construction of dozens of dams, autobahns,

railroads,

and other civil works. Hitler's policies emphasised the

importance of family life: men were the "breadwinners", while women's

priorities were to lie in bringing up children and in household work.

This revitalising of industry and infrastructure came at the expense of

the overall standard of living, at least for those not affected by the

chronic unemployment of the later Weimar Republic, since wages were

slightly reduced in pre-World War II years, despite a 25% increase in

the cost of living. Laborers and farmers, the

traditional voters of the NSDAP, however, saw an increase in their

standard of living. Hitler's

government sponsored architecture on an immense scale, with Albert

Speer becoming famous as the first architect of the Reich. While important as an architect in implementing Hitler's classicist

reinterpretation of German culture, Speer proved much more effective as

armaments minister during the last years of World War II. In 1936,

Berlin hosted the summer

Olympic

games, which were opened by Hitler and choreographed to demonstrate Aryan

superiority over all other races, achieving mixed results. Although

Hitler made plans for a Breitspurbahn ("broad

gauge railroad

network"), they were preempted by World War II. Had the railroad been

built, its gauge would have been three metres, even wider than the old Great

Western

Railway of

Britain. Hitler

contributed slightly to the design of the car that later became the Volkswagen

Beetle and charged Ferdinand

Porsche with its

design and construction. Production was deferred

because of the war. Hitler

considered Sparta to be the first National

Socialist state, and praised its early eugenics treatment of deformed

children. On 20

April 1939, a lavish celebration was held in honour of Hitler's

50th

birthday, featuring military parades, visits from foreign

dignitaries, thousands of flaming torches and Nazi banners. An

important historical debate about Hitler's economic policies concerns

the "modernization" debate. Historians such as David

Schoenbaum and Henry

Ashby

Turner have

argued that social and economic polices under Hitler were modernization

carried out in pursuit of anti-modern goals. Other groups of historians

centred around Rainer

Zitelmann have

contended that Hitler had a deliberate strategy of pursuing a

revolutionary modernization of German society. In a

meeting with his leading generals and admirals on 3 February 1933,

Hitler spoke of "conquest of Lebensraum in the East and its

ruthless Germanisation" as his ultimate foreign policy objectives. In March 1933, the first

major statement of German foreign policy aims appeared with the memo

submitted to the German Cabinet by the State Secretary at the Auswärtiges

Amt (Foreign

Office), Prince Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow (not to be confused

with his more famous uncle, the former Chancellor Bernhard

von

Bülow), which advocated Anschluss with Austria, the

restoration of the frontiers of 1914, the rejection of the Part V of

Versailles, the return of the former German colonies in Africa, and a

German zone of influence in Eastern

Europe as goals for

the future. Hitler found the goals in Bülow's memo to be too modest. In March 1933, to resolve

the deadlock between the French demand for sécurité ("security") and the German

demand for gleichberechtigung ("equality of armaments")

at the World

Disarmament

Conference in Geneva, Switzerland, the British Prime

Minister Ramsay MacDonald presented

the compromise "MacDonald Plan". Hitler endorsed the "MacDonald Plan",

correctly guessing that nothing would come of it, and that in the

interval he could win some goodwill in London by making his government

appear moderate, and the French obstinate. In May

1933, Hitler met with Herbert

von

Dirksen, the German Ambassador in Moscow. Dirksen advised the Führer that he was allowing

relations with the Soviet Union to deteriorate to a unacceptable

extent, and advised to take immediate steps to repair relations with

the Soviets. Much to Dirksen's intense

disappointment, Hitler informed that he wished for an anti-Soviet

understanding with Poland, which Dirksen protested implied recognition

of the German-Polish border, leading Hitler to state he was after much

greater things than merely overturning the Treaty

of

Versailles. In June

1933, Hitler was forced to disavow Alfred

Hugenberg of the

German National People's Party, who while attending the London

World

Economic Conference put

forth

a programme of colonial expansion in both Africa and Eastern

Europe, which created a major storm abroad. Speaking to the

Burgermeister of Hamburg in

1933, Hitler commented

that Germany required several years of peace before it could be

sufficiently rearmed enough to risk a war, and until then a policy of

caution was called for. In his "peace speeches" of

17 May 1933, 21 May 1935, and 7 March 1936, Hitler stressed his

supposed pacific goals and a willingness to work within the

international system. In private, Hitler's plans

were something less than pacific. At the first meeting of his Cabinet

in 1933, Hitler placed military spending ahead of unemployment relief,

and indeed was only prepared to spend money on the latter if the former

was satisfied first. When the president of the Reichsbank, the

former Chancellor Dr.Hans

Luther, offered the new government the legal limit of

100 million Reichmarks to finance rearmament, Hitler

found the sum too low, and sacked Luther in March 1933 to

replace him with Hjalmar

Schacht, who during the next five years was to advance

12 billion Reichmarks worth of "Mefo-bills" to

pay for rearmament. A major

initiative in Hitler's foreign policy in his early years was to create

an alliance with Britain. In the 1920s, Hitler wrote that a future

National Socialist foreign policy goal was "the destruction of Russia with the help of England." In May 1933, Alfred

Rosenberg in his

capacity as head of the Nazi Party's Aussenpolitisches

Amt (Foreign

Political Office) visited London as part of a disastrous effort to win

an alliance with Britain. In October 1933, Hitler

pulled Germany out of both the League

of

Nations and World

Disarmament

Conference after

his Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin

von

Neurath made it

appear to world public opinion that the French demand for sécurité was the principal stumbling

block. In line

with the views he advocated in Mein

Kampf and Zweites

Buch about the

necessity of building an Anglo-German alliance, Hitler, in a meeting in

November 1933 with the British Ambassador, Sir Eric

Phipps, offered a scheme in which Britain would support a

300,000-strong German Army in exchange for a German "guarantee" of the British

Empire. In response, the British

stated a 10-year waiting period would be necessary before Britain would

support an increase in the size of the German Army. A

more

successful initiative in foreign policy occurred with relations

with Poland. In spite of intense opposition from the military and the Auswärtiges Amt who preferred closer ties

with the Soviet

Union, Hitler, in the fall of 1933 opened secret talks with Poland

that were to lead to the German–Polish

Non-Aggression

Pact of

January 1934. In

February 1934, Hitler met with the British Lord Privy Seal, Sir Anthony

Eden, and hinted strongly that Germany already possessed an Air Force, which had been forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. In the fall of 1934, Hitler

was seriously concerned over the dangers of inflation damaging his popularity. In a secret speech given

before his Cabinet on 5 November 1934, Hitler stated he had "given the

working class his word that he would allow no price increases.

Wage-earners would accuse him of breaking his word if he did not act

against the rising prices. Revolutionary conditions among the people

would be the further consequence." Although

a secret German armaments programme had been on-going since 1919, in

March 1935, Hitler rejected Part V of the Versailles treaty by publicly

announcing that the German

army would be

expanded to 600,000 men (six times the number stipulated in the Treaty

of Versailles), introducing an Air Force (Luftwaffe)

and

increasing the size of the Navy (Kriegsmarine).

Britain,

France, Italy and the League of Nations quickly condemned

these actions. However, after re-assurances from Hitler that Germany

was only interested in peace, no country took any action to stop this

development and German re-armament continued. Later in March 1935,

Hitler held a series of meetings in Berlin with the British Foreign

Secretary Sir

John

Simon and

Eden, during which he successfully evaded British offers for German

participation in a regional security pact meant to serve as an Eastern

European equivalent of the Locarno

pact while the two

British ministers avoided taking up Hitler's offers of alliance. During his talks with Simon

and Eden, Hitler first used what he regarded as the brilliant colonial

negotiating tactic, when Hitler parlayed an offer from Simon to return

to the League of Nations by demanding the return of the former German

colonies in Africa. Starting

in April 1935, disenchantment with how the Third Reich had developed in practice

as opposed to what had been promised led many in the Nazi Party, especially

the Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters; i.e., those

who joined the Party before 1930, and who tended to be the most ardent

anti-Semitics in the Party), and the SA into

lashing out against

Germany's Jewish minority as a way of expressing their frustrations

against a group that the authorities would not generally protect. The rank and file of the

Party were most unhappy that two years into the Third Reich, and despite

countless promises by Hitler prior to 1933, no law had been passed

banning marriage or sex between those Germans belonging to the "Aryan"

and Jewish "races". A Gestapo report from the spring of

1935 stated that the rank and file of the Nazi Party would "set in

motion by us from below," a solution to the "Jewish problem," "that the

government would then have to follow." As a result, Nazi Party

activists and the SA started a major wave of assaults, vandalism and

boycotts against German Jews. On 18

June 1935, the Anglo-German

Naval

Agreement (AGNA)

was signed in London which allowed for increasing the allowed German

tonnage up to 35% of that of the British navy. Hitler called the

signing of the AGNA "the happiest day of his life" as he believed the

agreement marked the beginning of the Anglo-German alliance he had

predicted in Mein

Kampf. This agreement was made

without consulting either France or Italy, directly undermined the

League of Nations and put the Treaty of Versailles on the path towards

irrelevance. After the signing of the

A.G.N.A., in June 1935 Hitler ordered the next step in the creation of

an Anglo-German alliance: taking all the societies demanding the

restoration of the former German African colonies and coordinating (Gleichschaltung)

them

into a new Reich Colonial League (Reichskolonialbund)

which

over the next few years waged an extremely aggressive propaganda

campaign for colonial restoration. Hitler had no real interest

in the former German African colonies. In Mein Kampf, Hitler had

excoriated the Imperial

German government

for pursuing colonial expansion in Africa prior to 1914 on the grounds

that the natural area for Lebensraum was Eastern Europe, not

Africa. It

was Hitler's intention

to use colonial demands as a negotiating tactic that would see a German

"renunciation" of colonial claims in exchange for Britain making an

alliance with the Reich on German terms. In the

summer of 1935, Hitler was informed that, between inflation and the

need to use foreign exchange to buy raw materials Germany lacked for

rearmament, there were only 5 million Reichmarks available for military

expenditure, and a pressing need for some 300,000 Reichmarks per day to

prevent food shortages. In August 1935, Dr. Hjalmar

Schacht advised

Hitler that the wave of anti-Semitic violence was interfering with the

workings of the economy, and hence rearmament. Following Dr. Schacht's

complaints, plus reports that the German public did not approve of the

wave of anti-Semitic violence, and that continuing police toleration of

the violence was hurting the regime's popularity with the wider public,

Hitler ordered a stop to "individual actions" against German Jews on 8

August 1935. From Hitler's perspective, it was imperative to bring in harsh new anti-Semitic laws as a

consolation prize for those Party members who were disappointed with

Hitler's halt order of 8 August, especially because Hitler had only

reluctantly given the halt order for pragmatic reasons, and his

sympathies were with the Party radicals. The annual Nazi Party Rally

held at Nuremberg in September 1935 was to feature the first session of

the Reichstag held at that city since

1543. Hitler had planned to have the Reichstag pass a law making the Nazi

Swastika flag the flag of the German Reich,

and

a major speech in support of the impending Italian aggression

against Ethiopia. Hitler felt that the

Italian aggression opened great opportunities for Germany. In August

1935, Hitler told Goebbels his foreign policy vision as: "With England

eternal alliance. Good relationship with Poland . . .

Expansion to the East. The Baltic belongs to us . . .

Conflicts Italy-Abyssinia-England, then Japan-Russia imminent." At the

last minute before the Nuremberg Party Rally was due to begin, the

German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin

von

Neurath persuaded Hitler to cancel his speech praising Italy for

her willingness to commit aggression. Neurath convinced Hitler that his

speech was too provocative to public opinion abroad as it contradicted

the message of Hitler's "peace speeches", thus leaving Hitler with the

sudden need to have something else to address the first meeting of the Reichstag in Nuremberg since 1543,

other than the Reich Flag Law. On 13 September 1935,

Hitler hurriedly ordered two civil servants, Dr. Bernhard Lösener

and Franz Albrecht Medicus of the Interior Ministry to fly to Nuremberg

to start drafting anti-Semitic laws for Hitler to present to the Reichstag for 15

September. On the evening of 15

September, Hitler presented two laws before the Reichstag banning sex and marriage

between Aryan and Jewish Germans, the employment of Aryan women under

the age of 45 in Jewish households, and deprived "non-Aryans" of the

benefits of German citizenship. The laws of September 1935 are generally known as the Nuremberg

Laws. In

October 1935, in order to prevent further food shortages and the

introduction of rationing, Hitler reluctantly ordered cuts in military

spending. In the spring of 1936 in

response to requests from Richard

Walther

Darré, Hitler ordered 60 million Reichmarks of foreign exchange to be

used to buy seed oil for German farmers, a decision that led to bitter

complaints from Dr. Schacht and the War Minister Field Marshal Werner

von

Blomberg that

it would be impossible to achieve rearmament as long as foreign

exchange was diverted to preventing food shortages. Given the economic problems

which was affecting his popularity by early 1936, Hitler felt the

pressing need for a foreign policy triumph as a way of distracting

public attention from the economy. In an

interview with the French journalist Bertrand

de

Jouvenel in

February 1936, Hitler appeared to disavow Mein Kampf by saying that parts of his

book were now out of date and he was not guided by them, though

precisely which parts were out of date was left unclear. In March 1936, Hitler again

violated the Versailles treaty by reoccupying the demilitarized

zone in the

Rhineland. When Britain and France did nothing, he grew bolder. In July

1936, the Spanish

Civil

War began

when the military, led by General Francisco

Franco, rebelled against the elected Popular

Front government.

After receiving an appeal for help from General Franco in July 1936,

Hitler sent troops to support Franco, and Spain served as a testing

ground for Germany's new forces and their methods. At the same time,

Hitler continued with his efforts to create an Anglo-German alliance.

In July 1936, he offered to Phipps a promise that if Britain were to

sign an alliance with the Reich, then

Germany would commit to sending twelve divisions to the Far East

to protect British colonial possessions there from a Japanese attack. Hitler's offer was refused. In August

1936, in response to a growing crisis in the German economy caused by

the strains of rearmament, Hitler issued the "Four-Year Plan Memorandum" ordering Hermann

Göring to

carry out the Four

Year

Plan to have

the German economy ready for war within the next four years. During the 1936 economic

crisis, the German government was divided into two factions, with one

(the so-called "free market" faction) centring around the Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht

and the former Price Commissioner Dr. Carl

Friedrich

Goerdeler calling for decreased military spending and a turn away from autarkic policies, and another

faction around Göring calling for the opposite. Supporting the

"free-market" faction were some of Germany's leading business

executives, most notably Hermann Duecher of AEG,

Robert Bosch of Robert

Bosch

GmbH, and Albert Voegeler of Vereinigte

Stahlwerke

AG. Hitler hesitated for the

first half of 1936 before siding with the more radical faction in his

"Four Year Plan" memo of August. Historians such as Richard

Overy have argued

that the importance of the memo, which was written personally by

Hitler, can be gauged by the fact that Hitler, who had something of a

phobia about writing, hardly ever wrote anything down, which indicates

that Hitler had something especially important to say. The "Four-Year Plan

Memorandum" predicated an imminent all-out, apocalyptic struggle

between "Judo-Bolshevism" and German National Socialism, which

necessitated a total effort at rearmament regardless of the economic

costs. In the memo, Hitler wrote: Since

the outbreak of the French Revolution, the world has been moving with

ever increasing speed toward a new conflict, the most extreme solution

of which is called Bolshevism, whose essence and aim, however, are

solely the elimination of those strata of mankind which have hitherto

provided the leadership and their replacement by worldwide Jewry. No

state will be able to withdraw or even remain at a distance from this

historical conflict . . . It is not the aim of this

memorandum to prophesy the time when the untenable situation in Europe

will become an open crisis. I only want, in these lines, to set down my

conviction that this crisis cannot and will not fail to arrive and that

it is Germany's duty to secure her own existence by every means in face

of this catastrophe, and to protect herself against it, and that from

this compulsion there arises a series of conclusions relating to the

most important tasks that our people have ever been set. For a victory

of Bolshevism over Germany would not lead to a Versailles treaty, but

to the final destruction, indeed the annihilation of the German

people . . . I consider it necessary for the Reichstag to pass the following two

laws: 1) A law providing the death penalty for economic sabotage and 2)

A law making the whole of Jewry liable for all damage inflicted by

individual specimens of this community of criminals upon the German

economy, and thus upon the German people. Hitler

called for Germany to have the world's "first army" in terms of

fighting power within the next four years and that "the extent of the

military development of our resources cannot

be

too large, nor its pace too swift" (italics in the original) and

the role of the economy was simply to support "Germany's self-assertion

and the extension of her Lebensraum." Hitler went on to write

that given the magnitude of the coming struggle that the concerns

expressed by members of the "free market" faction like Schacht and

Goerdeler that the current level of military spending was bankrupting Germany were irrelevant.

Hitler wrote that: "However well balanced the general pattern of a

nation's life ought to be, there must at particular times be certain

disturbances of the balance at the expense of other less vital tasks.

If we do not succeed in bringing the German army as rapidly as possible

to the rank of premier army in the world . . . then

Germany will be lost!" and

"The nation does not

live for the economy, for economic leaders, or for economic or

financial theories; on the contrary, it is finance and the economy,

economic leaders and theories, which all owe unqualified service in

this struggle for the self-assertion of our nation." Documents

such as the Four Year Plan Memo have often been used by right

historians such as Henry

Ashby

Turner and Karl

Dietrich

Bracher who

argue for a "primacy of politics" approach (that Hitler was not

subordinate to German business, but rather the contrary was the case)

against the "primacy of economics" approach championed by Marxist

historians (that Hitler was a "agent" of and subordinate to German

business). In August

1936, the freelance Nazi diplomat Joachim

von

Ribbentrop was

appointed German Ambassador to the Embassy

of

Germany in London at

the Court

of

St. James's. Before Ribbentrop left to take up his post in

October 1936, Hitler told him: "Ribbentrop . . . get

Britain to join the Anti-Comintern Pact, that is what I want most of

all. I have sent you as the best man I've got. Do what you

can . . . But if in future all our efforts are still in

vain, fair enough, then I'm ready for war as well. I would regret it

very much, but if it has to be, there it is. But I think it would be a

short war and the moment it is over, I will then be ready at any time

to offer the British an honourable peace acceptable to both sides.

However, I would then demand that Britain join the Anti-Comintern Pact

or perhaps some other pact. But get on with it, Ribbentrop, you have

the trumps in your hand, play them well. I'm ready at any time for an

air pact as well. Do your best. I will follow your efforts with

interest". An Axis

was declared between Germany and Italy by Count Galeazzo

Ciano, foreign minister of Fascist dictator Benito

Mussolini, on 25

October 1936. On 25 November of the same year, Germany concluded the Anti-Comintern

Pact with Japan. At

the time of the signing of the Anti-Comintern Pact, invitations were

sent out for Britain, China, Italy and Poland to adhere; of the invited

powers only the Italians were to sign the pact, in November 1937. To

strengthen relationship with Japan, Hitler met in 1937 in Nuremberg Prince

Chichibu, a brother of emperor Hirohito.

However,

the meeting with Prince Chichibu had little consequence, as

Hitler refused the Japanese request to halt German arms shipments to

China or withdraw the German officers serving with the Chinese in the Second

Sino-Japanese

War. Both the military and the Auswärtiges

Amt (Foreign

Office) were

strongly opposed to ending the informal German

alliance

with China that

existed since the 1910s, and pressured Hitler to avoid offending the

Chinese. TheAuswärtiges Amt and the military both

argued to Hitler that given the foreign exchange problems which

afflicted German rearmament, and the fact that various Sino-German

economic agreements provided Germany with raw materials that would

otherwise use up precious foreign exchange, it was folly to seek an

alliance with Japan that would have the inevitable result of ending the

Sino-German alignment. By the

latter half of 1937, Hitler had abandoned his dream of an Anglo-German

alliance, blaming "inadequate" British leadership for turning down his

offers of an alliance. In a talk with the League

of Nations High Commissioner for the Free

City

of Danzig, the Swiss diplomat Carl

Jacob Burckhardt in

September 1937, Hitler protested what he regarded as British

interference in the "German sphere" in Europe, though in the same talk,

Hitler made clear his view of Britain as an ideal ally, which for pure

selfishness was blocking German plans. Hitler

had suffered severely from stomach pains and eczema in 1936–37, leading

to his remark to the Nazi Party's propaganda leadership in October 1937

that because both parents died early in their lives, he would probably

follow suit, leaving him with only a few years to obtain the necessary Lebensraum. About the same time, Dr.

Goebbels noted in his diary Hitler now wished to see the "Great Germanic Reich" he envisioned

in his own lifetime rather than leaving the work of building the "Great

Germanic Reich" to his successors. On 5

November 1937, at the Reich Chancellory, Adolf

Hitler held a secret meeting with the War and Foreign Ministers and the

three service chiefs, recorded in the Hossbach

Memorandum, and stated his intentions for acquiring "living space" Lebensraum for the German people. He

ordered the attendees to make plans for war in the east no later than

1943 in order to acquire Lebensraum.

Hitler

stated the conference minutes were to be regarded as his

"political testament" in the event of his death. In the memo, Hitler was

recorded as saying that such a state of crisis had been reached in the

German economy that the only way of stopping a severe decline in living

standards in Germany was to embark sometime in the near-future on a