<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Norman Earl Steenrod, 1910

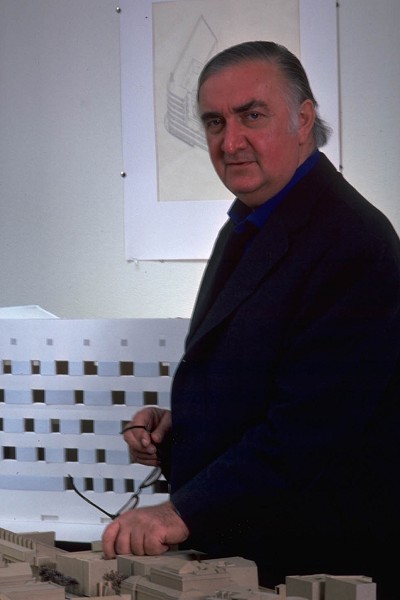

- Architect James Frazer Stirling, 1926

- Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars Vladimir Iliych Lenin, 1870

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir James Frazer Stirling FRIBA (22 April 1926 in Glasgow – 25 June 1992 in London) was a British Architect considered to be among the most important and influential architects of the second half of the 20th century. He is perhaps best known as one of a number of young architects who from the 1950s on questioned and subverted the compositional and theoretical precepts of the first Modern Movement. Stirling's development of an agitated, mannered reinterpretation of those precepts – much influenced by his friend and teacher, the important architectural theorist and urbanist Colin Rowe – introduced an eclectic spirit that allowed him to plunder the whole sweep of architectural history as a source of compositional inspiration, from ancient Rome and the Baroque, to the many manifestations of the modern period, from Frank Lloyd Wright to Alvar Aalto. His success lay in his ability to incorporate these encyclopedaic references subtly, within a strong and muscular, very decisive architecture of strong, confident gestures that aimed to remake urban form.

After wartime service, Stirling studied architecture from 1945 until 1950 at the University of Liverpool, where Colin Rowe was his teacher. In 1956 he and James Gowan left their positions as assistants with the firm of Lyons, Israel, and Ellis to set up a practice as Stirling and Gowan. One of the best-known results of this collaboration are the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Leicester (1959 – 63), noted for its technological and geometric character, marked by the use of three-dimensional drawings based on axonometric projection seen either from above (in a bird's eye view) or below (in a worm's eye view); the History Faculty Library at the University of Cambridge; and The Florey Building accommodation block for The Queen's College, Oxford.

In 1963 Stirling and Gowan separated; Stirling then set up on his own, taking with him the office assistant Michael Wilford (who provided invaluable administrative help and later became a partner). From that point on the design task, which had previously been shared between Stirling and Gowan, remained very much under the control of Stirling, assisted by hand-picked helpers. He completed a training centre for Olivetti in Haslemere, Surrey, and housing for the University of St Andrews both of which made prominent use of re-fabricated elements, GRP for Olivetti and pre-cast concrete panels at St Andrews.

During the 1970s, Stirling's architectural language began to change as the scale of his projects moved from small and not very profitable to very large, as Stirling's architecture became more overtly neoclassical, though it remained deeply imbued with his powerful revised modernism. This produced a wave of dramatically spare, large-scale urban projects, most notably three important museum projects in Germany (for Düsseldorf, Cologne, and Stuttgart). These projects of the 1970s show him at the zenith of his mature style. Winning the design competition for the Stuttgart project – the Neue Staatsgalerie – he loaded its powerful basic concept with a large number of architectural amusements and decorative allusions, which led many to see it as an example of postmodernism – a label which then stuck, but which he himself rejected. In 1981, he was awarded the renowned Pritzker Prize. After the Staatsgalerie, Stirling received a series of important commissions in England – the Clore Gallery for the Turner Collection at the Tate Britain, London (1980 - 87), the Tate Liverpool (1984), and No 1 Poultry in London (1986). This work revealed a particular interest in public space, and the meanings that façades and building masses can assume in a constrained urban context.

The last building completed while Stirling was still alive was the bookshop in the gardens of the Venice Biennale (completed 1991). Designed with Thomas Muirhead, this building explored a sparer, more modernist approach. The Venice Bookshop and a number of other late projects were greeted by critics like Kenneth Frampton and others as the possible beginning of a new and potentially important departure in Stirling's work – had he not suddenly died, due to an unfortunate botched minor hospital operation. His sudden passing was considered a great tragedy for architecture; the Italian architect and critic Vittorio Gregotti wrote in "Casabella" magazine that "from now on, everything will be more difficult".

Just before his death he was given a knighthood (1992) which as a rebellious spirit, he only accepted with reluctance on the grounds that "it might be good for the office". In accordance with his wishes, his ashes are buried near to his memorial in the narthex at Christ Church Spitalfields

After the death of Stirling in 1992, Wilford took over and gradually wound the firm down whilst completing the work that remained in the pipeline and had been left by Stirling at various stages of development. Various buildings completed thereafter and often carelessly attributed to Stirling, such the State University of Music and Performing Arts Stuttgart, 1993 – 1994, or No 1 Poultry in London, were in fact completed and built by Wilford and his assistants. The practice no longer exists, and the complete office archive was sold to the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montréal. The Stirling Prize, a British annual prize for architecture since 1996, was named after him.

The

cultural depth and richness of Stirling's work attracted the attention

of all the major world critics and theoreticians, from Peter

Eisenman to Charles

Jencks, and the literature examining his architecture is vast. For

those seriously interested, the best starting point for further study

is the two published books of his complete works, which he oversaw

himself, aided by trusted friends and collaborators. These two books

chronologically cover every project and emphasise the visual, with

thousands of very carefully reproduced photographs, drawings, and

models.