<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Johannes (van Waveren) Hudde, 1628

- Painter Alfred Verwee Jacques, 1838

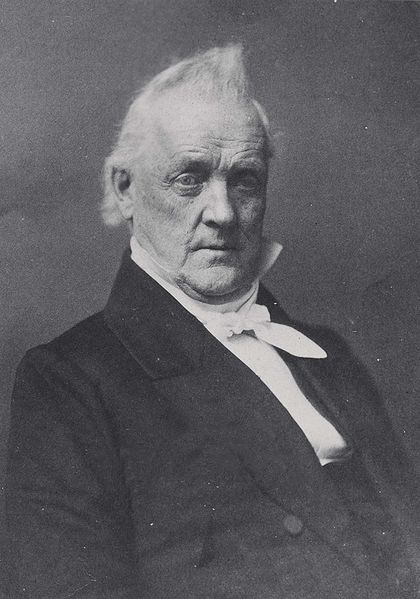

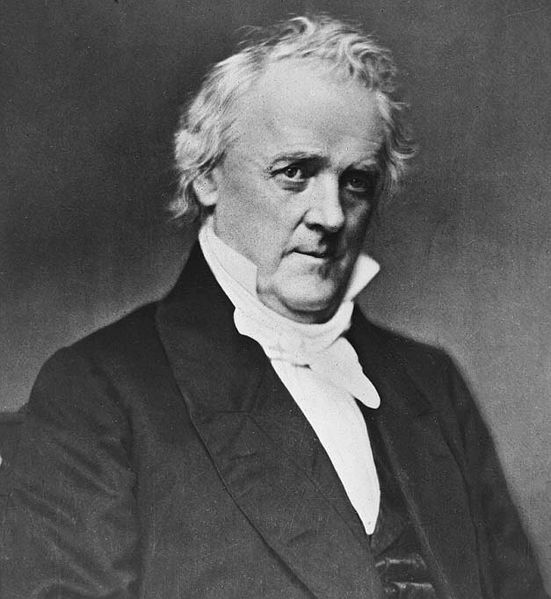

- 15th President of the United States James Buchanan, Jr., 1791

PAGE SPONSOR

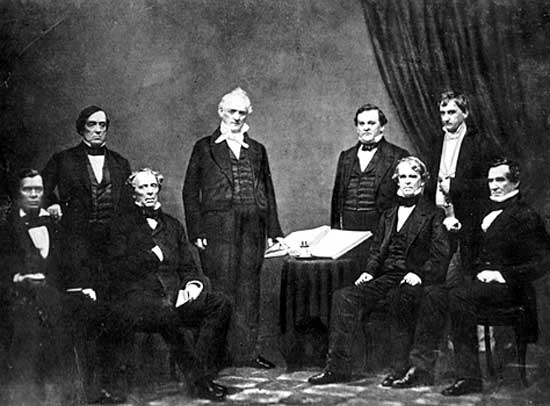

James Buchanan, Jr. (April 23, 1791 – June 1, 1868) was the 15th President of the United States from 1857 – 1861 and the last to be born in the 18th century. To date he is the only president from the state of Pennsylvania and the only one to have never married.

A popular

and experienced state politician and very successful attorney prior to

his presidency, Buchanan represented Pennsylvania in the U.S. House

of

Representatives and

later the Senate,

and

served as Minister

to

Russia under

President Andrew

Jackson. He also was Secretary

of

State under

President James

K.

Polk. After turning down an offer for an appointment to the Supreme

Court, he served as Minister

to

the United Kingdom under

President Franklin

Pierce, in which capacity he helped draft the controversial Ostend

Manifesto. After

unsuccessfully seeking the Democratic presidential nomination in 1844,

1848, and 1852, Buchanan was nominated in the election

of

1856 to some

extent as a compromise between the two sides of the slavery

issue; this occurred just after he completed his duties as a

Minister to England. His subsequent election victory took place in a

three-man race with Fremont and Fillmore. As President he was often

referred to as a "doughface",

a

Northerner with Southern sympathies who battled with Stephen

A.

Douglas for the

control of the Democratic

Party. Buchanan's efforts to maintain

peace between the

North and the South alienated both sides, and the Southern states

declared their secession in the prologue to the American

Civil

War. Buchanan's view of record was that secession was

illegal, but that going to war to stop it was also illegal. Buchanan,

first and foremost an attorney, was noted for his mantra, "I

acknowledge no master but the law." By the

time he left office, popular opinion had turned against him, and the

Democratic Party had split in two. Buchanan had once aspired to a

presidency that would rank in history with that of George

Washington. However, his inability to

impose peace on sharply divided partisans on the brink of the Civil War

has led to his consistent ranking by historians as one of the worst

Presidents. Noted Buchanan biographer Philip Klein puts these

rankings into context, as follows: "Buchanan assumed leadership ... when

an unprecedented wave of angry passion was sweeping over the nation.

That he held the hostile sections in check during these revolutionary

times was in itself a remarkable achievement. His weaknesses in the

stormy years of his presidency were magnified by enraged partisans of

the North and South. His many talents, which in a quieter era might

have gained for him a place among the great presidents, were quickly

overshadowed by the cataclysmic events of civil war and by the towering Abraham Lincoln." James

Buchanan, Jr., was born in a log

cabin in Cove

Gap, near Harrisburg (now James

Buchanan

Birthplace State Park), Franklin

County, Pennsylvania, on April 23, 1791, to James Buchanan, Sr.

(1761 – 1833), and Elizabeth Speer (1767 – 1833). His parents were both of Scotch-Irish descent, the father having

emigrated from northern Ireland in 1783. He was the second of eleven

children, three of whom died in infancy. Buchanan had six sisters and

four brothers, only one of whom lived past 1840. In 1797,

the family moved to nearby Mercersburg,

Pennsylvania. The home in Mercersburg was later turned into the James

Buchanan

Hotel. Buchanan

attended the village academy and later Dickinson

College in Carlisle,

Pennsylvania. Expelled at one point for poor behavior, after

pleading for a second chance, he graduated with honors on September 19,

1809. Later that year, he moved to Lancaster,

where

he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1812. A dedicated Federalist,

he

initially opposed the War

of

1812 on the

grounds that it was an unnecessary conflict; but, when the British

invaded neighboring Maryland,

he

joined a volunteer light dragoon unit and served in the defense of Baltimore. An active Freemason during his lifetime, he was

the Master of Masonic Lodge #43 in Lancaster,

Pennsylvania, and a District Deputy Grand

Master of the Grand

Lodge

of Pennsylvania. Buchanan

began his political career in the Pennsylvania

House

of Representatives from

1814 – 1816,

serving as a Federalist. He was elected to the 17th

United

States Congress and

to the four succeeding Congresses (March 4, 1821 – March 4, 1831),

serving as chairman of the U.S.

House

Committee on the Judiciary in

the 21st

United

States Congress. In 1830, he was among the members appointed by the House to conduct impeachment proceedings

against James

H.

Peck, judge of the United

States

District Court for the District of Missouri, who was

ultimately acquitted. Buchanan did not seek

reelection, and from 1832 to 1834 he served as Minister

to

Russia. With the

Federalist Party long defunct, Buchanan was elected as a Democrat to

the United

States

Senate to

fill a vacancy and served from December 1834; he was reelected in 1837

and 1843, and resigned in 1845 to accept President Polk's nomination of

him as Secretary of State. He was chairman of the Committee

on

Foreign Relations (24th

through

26th Congresses). After the

death of Supreme Court Justice Henry

Baldwin in 1844,

Buchanan was nominated by President

Polk to serve as a

Justice of the Supreme Court. He declined that nomination, despite

having earlier been interested in previous vacancies on the court; at

the time of this particular nomination, he felt compelled to complete

his collaboration on the Oregon Treaty negotiations; the Court seat was

filled by Robert Cooper

Grier. Buchanan

served as Secretary

of

State under

James K. Polk from 1845 to 1849, despite objections from Buchanan's

rival, Vice President George

Dallas. In this capacity, he helped

negotiate the 1846 Oregon

Treaty establishing

the 49th

parallel as the northern boundary of the western U.S. No

Secretary of State has become President since James Buchanan, although William

Howard

Taft, the 27th President of the United States, often served

as Acting Secretary of State during the Theodore

Roosevelt administration.

In 1852,

Buchanan was named president of the Board of Trustees of Franklin

and

Marshall College in

his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and he served in this capacity

until 1866, despite a false report that

he was fired. He served

as minister

to

the Court of St. James's (Britain)

from

1853 to 1856, during which time he helped to draft the Ostend

Manifesto, which proposed the purchase from Spain of Cuba,

then

in the midst of revolution and near bankruptcy. Against Buchanan's

recommendation, the final draft of the Manifesto suggested that the

U.S. should declare war if Spain refused to sell Cuba.

The

Manifesto, generally considered a blunder overall, was never acted

upon, but nevertheless weakened the Pierce administration and support for Manifest

Destiny. The

Democrats nominated Buchanan in 1856.

He

had been in England during the Kansas-Nebraska debate

and thus remained

untainted by either side of the issue. Pennsylvania, which had three

times failed Buchanan, now gave its full support in its state

convention. Though he never formally threw his hat into the ring, it is

apparent from all his correspondence, that he was quite aware of the

distinct possibility of his nomination by the Democratic convention in

Cincinnati, even before heading home at the finish of his work as

Minister to England. Dr. Jonathan Foltz told Buchanan in November of

1855: "The people have taken the next presidency out of the hands of

the politicians ... the people and not your political friends will

place

you there." While Buchanan did not overtly seek the office, he most

deliberately chose not to discourage the movement on his behalf,

something that was well within his power on many occasions. Former

president Millard

Fillmore's "Know-Nothing"

candidacy

helped Buchanan defeat John

C.

Frémont, the first Republican candidate for president in

1856, and he served from March 4, 1857 to March 4, 1861. Buchanan

remains the most recent of the two Democrats (the other being Martin

Van

Buren) to succeed a fellow Democrat to the Presidency via

election in his own right. With

regard to the growing schism in the country, as President-elect,

Buchanan

stated: "the object of my administration will be to destroy sectional party, North or South, and to restore harmony to the Union

under a national and conservative government'. He set about this initially

by maintaining a sectional balance in his appointments and persuading

the people to accept constitutional law as the Supreme

Court interpreted

it. The court was considering the legality of restricting slavery in

the territories and two justices had hinted to Buchanan what the

decision would be.

In

his inaugural

address,

in addition to promising not to run again, Buchanan

referred to the territorial question as "happily, a matter of but

little practical importance" since the Supreme Court was about to

settle it "speedily and finally." Two days later, Chief Justice Roger B.

Taney delivered

the Dred

Scott

Decision, asserting that Congress had no constitutional power to exclude slavery in

the territories. Part of Taney’s written judgment has been

characterized as obiter

dictum — statements commonly made by a jurist that are not

central to the decision in the case; in this instance such comments

delighted Southerners while creating a furor in the North. Buchanan, in

his view, preferred to see the territorial question resolved by the

Supreme Court. It is known that he was told of the Court's decision a

week before his inauguration. Abraham

Lincoln denounced

him as an accomplice of the Slave

Power, which Lincoln saw as a conspiracy of slave owners to seize

control of the federal government and nationalize slavery. However, there is

no extant contemporaneous statement that Buchanan interfered in the

Court's rendering of the Dred Scott decision. In 1854

Buchanan encountered trouble in the territorial dispute in Kansas,

dubbed Bleeding

Kansas by the

Republican Party. During its development in the Pierce administration,

Kansas found itself in the throes of abolitionist and proslavery

factions of settlers. The proslavery settlers decided to establish a

seat of government in Lecompton, while the abolitionists organized a

rival government in Topeka. Nevertheless, in order to achieve

statehood, the territory needed to submit to Washington one state

constitution adopted by all Kansans. Toward this end, Buchanan

appointed Robert Walker as Governor and dispatched him to the

territory. It was Walker's mission to reduce the divisiveness and

ensure a fair and full vote by all the people in the formation of a

Kansas constitution. Walker acted poorly in terms of tamping down the

partisanship; the result was a census, and ultimate voting process,

conducted (and corrupted to a degree) by partisans on both sides.

Kansans thus adopted the Lecompton

Constitution but

all the disputes began anew. Buchanan's

exclusive

goal was the legal admission of Kansas to the United States

and the end of dueling governments in the territory. He threw the

support of his administration behind congressional approval of the

Lecompton Constitution, which, flawed as it was, had been adopted with

due process by the people of Kansas, and would grant admission of

Kansas as a state, albeit predominantly proslavery due to the manner in

which irregular voting took place. Paradoxically, the President made

every effort, legal or not, to obtain Congressional approval for Kansas

statehood, offering favors, patronage appointments and even cash in

exchange for votes. The Lecompton government was unpopular among

Northerners because it was dominated by slaveholders who had enacted

laws curtailing the rights of non-slaveholders. The Lecompton bill

passed through the House, but it was blocked in the Senate by

Northerners led by Stephen A.

Douglas.

Eventually, Congress voted to call a new vote on the

Lecompton Constitution which succeeded, a move which infuriated

Southerners. Buchanan and Douglas engaged in an all-out struggle for

control of the party in 1859 – 60, with Buchanan using his patronage

powers and Douglas rallying the grass roots. The result was a further

weakened party and government. Buchanan

considered the essence of good self government to be founded upon restraint.

The

constitution he considered to be "...restraints, imposed not by

arbitrary authority, but by the people upon themselves and their

representatives... In an enlarged view, the people's interests may seem

identical, but "to the eye of local and sectional prejudice, they

always appear to be conflicting... and the jealousies that will

perpetually arise can be repressed only by the mutual forbearance which

pervades the constitution." As to the

economy, one of the greatest issues of the day was the tariff. Buchanan

condemned both free trade and prohibitive tariffs, since either system

would benefit one section of the country to the detriment of the other.

As the Senator from Pennsylvania, he thought: "I am viewed as the

strongest advocate of protection in other states, whilst I am denounced

as its enemy in Pennsylvania." Buchanan,

like many of his time, was torn between his interest in the expansion

of the country for the benefit of all, and the insistence of the people

settling the expanded areas to all of their rights, including some

rights not beneficial to all, i.e. slavery. On territorial expansion,

he said, "What, sir! Prevent the people from crossing the Rocky

Mountains? You might just as well command the Niagara not to flow. We

must fulfill our destiny." On the resulting spread of

slavery, through unconditional expansion, he stated: "I feel a strong

repugnance by any act of mine to extend the present limits of the Union

over a new slave-holding territory." For instance, he hoped the

acquisition of Texas would "be the means of limiting, not enlarging,

the dominion of slavery." Nevertheless,

in

deference to the intentions of the typical slaveholder, he was quick

to provide the benefit of much doubt. In his third annual message

Buchanan claimed that the slaves were "treated with kindness and

humanity.... Both the philanthropy and the self-interest of the master

have combined to produce this humane result." Historian

Kenneth Stampp wrote: "Shortly after his election, he assured a

southern Senator that the "great object" of his administration would be

"to arrest, if possible, the agitation of the Slavery question in the

North and to destroy sectional parties. Should a kind Providence enable me to succeed in my

efforts to restore harmony to the Union, I shall feel that I have not

lived in vain." In the northern anti-slavery idiom of his day, Buchanan

was often considered a "doughface,"

a

northern man with southern principles.

The

President, however, also felt that "this question of domestic slavery

is the weak point in our institutions, touch this question

seriously ... and the Union is from that moment dissolved. Although in

Pennsylvania we are all opposed to slavery in the abstract, we can

never violate the constitutional compact we have with our sister

states. Their rights will be held sacred by us. Under the constitution

it is their own question; and there let it remain." As

regards the abolitionist movement, Buchanan was irked that the

abolitionists were preventing the very result everyone sought, the

solution of the slavery problem. He stated, " Before [the

abolitionists] commenced this agitation, a very large and growing party

existed in several of the slave states in favor of the gradual

abolition of slavery; and now not a voice is heard there in support of

such a measure. The abolitionists have postponed the emancipation of

the slaves in three or four states for at least half a century." On

educational issues, it has been said that Buchanan's disinterest was

greatly evidenced by his veto of a bill passed by Congress to create

more colleges, for he believed that "there were already too many

educated people." In fact, the bill he vetoed

was a ruse for a federal land donation act designed to benefit Rep.

John Covode's railroad company, and fashioned to appear as a land grant

for new agricultural colleges. As

to his

religious convictions, near the end of his administration he had a

serious exchange with the Rev. William Paxton. After what Paxton

described as quite a probative discussion, Buchanan said, "Well,

sir... I hope I am a Christian. I have much of the experience you have

described, and as soon as I retire, I will unite with the Presbyterian

Church." Paxton asked why he delayed, to which he replied, "I must

delay for the honor of religion. If I were to unite with the church

now, they would say 'hypocrite' from Maine to Georgia."

In

August

suddenly came the Panic

of

1857, brought on mostly by 1) the people's over-consumption of

goods from Europe to such an extent that the Union's Specie was drained off; 2)

overbuilding by competing railroads; and 3) rampant land speculation in

the west. Most of the state banks had overextended credit, to more than

$7.00 for each dollar of gold or silver. The Republicans considered the

Congress to be the culprit for having recently reduced tariffs.

Buchanan's response was reform not relief.

The government would

continue to pay its debts in specie, and while it would not curtail

public works, none would be added. He urged the states to restrict the

banks to a credit level of $3 to $1 of specie, and discouraged the use

of federal or state bonds as security for bank note issues. The economy

did eventually recover on the shoulders of determined individuals able

and willing making difficult but sound business choices. Nevertheless,

the recovery came only after many lives had suffered despair, poverty

and even starvation. The South was considered to

have been less severely effected, due to "King Cotton", than the North

where manufacturers were hardest hit.

In

March

1857, Buchanan received conflicting and unconfirmed reports from

federal judges in Utah that their offices had been disrupted and they

had been driven from their posts by the Mormons. While some of these

reports may have been accurate, historically the Mormons had genuine

complaints against the federal government's actions in the territory.

The Pierce administration had refused to facilitate Utah's being

granted statehood and the Mormons feared the loss of their property

rights. In November of that year, Buchanan sent the Army to replace

Brigham Young as Governor with the non-Mormon Alfred

Cumming. While the Mormons' defiance of federal authority in the

past had become traditional, it is said this was not justification for

Buchanan's action on uncorroborated reports. Also, Young's notice of his

replacement was not delivered because the Pierce administration had

annulled the Utah mail contract. After a reaction by Young

in which he led a two week expedition destroying wagon trains, oxen and

other property, Buchanan dispatched Thomas L.

Kane as a

private agent to make peace. The mission succeeded, the new governor

was shortly placed in office, and the Utah War ended. The

President granted amnesty to all inhabitants who would respect the

authority of the government, and moved the federal troops to a

non-threatening distance for the balance of his administration. The

division between northern and southern Democrats allowed the

Republicans to win a plurality in the House in the election

of

1858. Their control of the chamber allowed the Republicans to

block most of Buchanan's agenda (including his proposals for expansion

of influence in Central America, and for the purchase of Cuba).

Buchanan

thought the ideologies of the Unites States would bring peace

and prosperity to these neighboring lands as they had in the Northwest

and that in the absence of U.S. influence, the major European powers

would intervene. The imperative of safe and speedy travel from east to

west was of strategic importance to the country. In any case, these

goals would not be reached . Buchanan, in turn, vetoed six substantial

pieces of Republican legislation, generating even further hostilities

between Congress and the White House. In March

1860 the House created the

Covode

Committee to

investigate the administration for evidence of offenses, some

impeachable, such as bribery and extortion of Congressmen in exchange

for their votes. The Committee for its part was nakedly partisan, with

three Republicans and one Democrat, and Buchanan enemy John Covode as

chairman; the group leaked damaging information about the President

without affording him the chance to testify or respond officially; the

committee was unable to establish grounds for impeaching Buchanan, but

its final report in June exposed a level of corruption and abuse of

power among members of his Cabinet; practices which had become common

since the days of the Jackson administration. In several incidents, the

Buchanan administration assisted the Committee in exposing and

correcting abuses during the investigation. Republican operatives

distributed thousands of copies of the Covode Committee report

throughout

the nation as campaign material in that year's presidential election. Sectional

strife rose to such a pitch that the Democratic Party's national

convention in 1860 led directly to a schism in the Party. Buchanan

played very little part as the national convention, meeting in Charleston,

South

Carolina, deadlocked. The southern wing walked out of the

convention and nominated its own candidate for the presidency,

incumbent Vice President John

C.

Breckinridge. The remainder of the party finally nominated

Buchanan's archenemy, Stephen Douglas. Consequently, when the

Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln, it was a foregone conclusion

that on November 6, 1860 he would be elected even though his name

appeared on the ballot only in the free states, Delaware, and a handful

of other border states. As early

as October, the army's Commanding

General, Winfield

Scott,

warned Buchanan that the election of Lincoln would likely

lead to the secession of at least seven states. He also quite

disingenuously recommended to Buchanan that massive amounts of federal

troops and artillery be deployed to those states to protect federal

property. After Lincoln's election Buchanan directed War Secretary

Floyd to reinforce southern forts with such provisions, arms and men as

were available. Nevertheless, through no fault of Scott or the

President, Congress had since 1857 failed to heed both men's calls on

behalf of a stronger militia and had allowed the Army to fall into

deplorable condition. Scott himself had previously advised the Senate

that the level of troops was such that "to move any substantial number

of troops from one frontier to reinforce another would invite instant

attack on the weakened point". With

Lincoln's victory, talk of secession and disunion reached a boiling

point of such proportion that Buchanan's final message to Congress, due

the month after the election, could not help but address it; both

factions eagerly awaited news of how Buchanan would deal with the

question. In his Message (December 3, 1860),

Buchanan both denied the legal right of states to secede and also held

that the Federal Government legally could not prevent them.

Furthermore, he placed the blame for the crisis solely on "intemperate

interference of the Northern people with the question of slavery in the

Southern States."

Buchanan's

specific solution to the crisis was that the Congress, in

coordination with the state legislatures, call for a constitutional

convention which would give the people of the country the opportunity

to vote specifically on amendment to the constitution regarding the

slavery issue. There was no ability to reach agreement on this approach

as a solution to be pursued. South

Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860 followed by six other cotton

states and, by

February 1861, they had formed the Confederate States

of America. As Scott had surmised, the secessionist

governments declared eminent domain over federal property within their

states. Efforts

were made by Sen. Crittenden and others in Congress, which were

supported by Buchanan, to reach a compromise, but failed. Failed

efforts to compromise were also made by a group of governors meeting in

New York. Buchanan employed a last minute tactic, in secret, to bring a

solution. He again attempted in vain to procure President-elect

Lincoln's call for a constitutional convention to give the citizens a

popular vote on slavery and other issues. Lincoln declined, at least

partially in deference to his party and its Chicago platform. Beginning

in late December, Buchanan reorganized his cabinet, ousting Confederate

sympathizers and replacing them with hard-line nationalists Jeremiah

S.

Black, Edwin

M.

Stanton, Joseph

Holt and John

A.

Dix. These conservative Democrats strongly believed

in American nationalism and refused to countenance secession. At one

point, Treasury Secretary Dix ordered Treasury agents in New Orleans, "If any man pulls down the American

flag, shoot him on the spot." The new cabinet advised Buchanan to

request from Congress the authority to call up militias and give

himself emergency military powers, and this he did, on January 8, 1861.

Nevertheless, by that time Buchanan's relations with Congress were so

strained that his requests were rejected out of hand. Before

Buchanan left office, all arsenals and forts in the seceding states

were lost (except Fort

Sumter and three

island outposts in Florida), and a fourth of all federal soldiers

surrendered to Texas troops. The government

retained control of Fort Sumter, which was located in Charleston harbor, a conspicuously

visible spot in the Confederacy. On January 5, Buchanan sent a civilian

steamer Star

of

the West to

carry reinforcements and supplies to Fort Sumter. On January 9, 1861, South

Carolina state

batteries opened fire on the Star of

the West, which

returned to New

York. Buchanan, having no authorization from Congress as requested,

made no further moves to prepare for war. On

Buchanan's final day as president, March 4, 1861, he remarked to the

incoming Lincoln, "If you are as happy in entering the White

House as I shall

feel on returning to Wheatland,

you

are a happy man."

In

1819,

Buchanan was engaged to Ann Caroline Coleman, the daughter of a

wealthy iron manufacturing businessman

and sister-in-law of Philadelphia judge Joseph

Hemphill, a colleague of Buchanan's from the House

of

Representatives. However, Buchanan spent little time with her

during the courtship. He was extremely busy with his law firm and

political projects during the Panic of

1819,

taking him away from Coleman for weeks at a time.

Conflicting rumors abounded, suggesting that he was marrying her for

her money as his own family was less affluent or that he was involved

with other women. Buchanan, for his part, never publicly spoke of his

motives or feelings, but letters from Ann revealed she was paying heed

to the rumors. After Buchanan paid a visit to the wife of a friend, Ann

broke off the engagement; she died soon afterwards, on December 9,

1819. The records of a Dr. Chapman, who looked after her in her final

hours, and who said just after her passing that this was "the first

instance he ever knew of hysteria producing death",

reveal that he theorized, despite the absence of any valid

evidence, the woman's demise was caused by an overdose of laudanum,

a

concentrated tincture of opium. His fiancée's death

struck Buchanan a terrible blow. In a letter to her father which was

returned to him unopened, Buchanan said, "It is now no time for

explanation, but the time will come when you will discover that she, as

well as I, have been much abused. God forgive the authors of it.... I

may sustain the shock of her death, but I feel

that happiness has fled from me forever." The Coleman family became

bitter towards Buchanan and denied him a place at Ann's funeral. Buchanan vowed he would

never marry, though he continued to be flirtatious, and some pressed

him to seek a wife. In response Buchanan said, "Marry I could not, for

my affections were buried in the grave." He preserved Ann Coleman's

letters, keeping them with him throughout his life, and, at his

request, they were burned upon his death. For 15

years in Washington,

D.C., prior to his presidency, Buchanan lived with his close friend, Alabama Senator William

Rufus

King. King became Vice

President under Franklin

Pierce. He became ill and died shortly after Pierce's inauguration,

just four years before Buchanan became President. Buchanan and King's

close relationship prompted Andrew

Jackson to refer to

King as "Miss Nancy" and "Aunt Fancy", while Aaron

V.

Brown spoke of

the two as "Buchanan and his wife." Further, some of the

contemporary press also speculated about Buchanan and King's

relationship. Buchanan and King's nieces destroyed their uncles'

correspondence, leaving some questions as to what relationship the two

men had, but the length and intimacy of surviving letters illustrate

"the affection of a special friendship" and Buchanan wrote of his

"communion" with his housemate. Such expression, however,

was not necessarily unusual among men at that time. Circumstances

surrounding Buchanan and King's close emotional ties have led to

speculation that Buchanan was a homosexual. This

speculation is perhaps made more tenuous by Buchanan's correspondence

during this period with Thomas Kittera, referring to his romance with

Mary K. Snyder, and his letter to Mrs. Francis Preston Blair, in which

he declines an invitation and expresses an expectation of marriage. In his

book, Lies Across

America, James

W.

Loewen points

out that in May 1844, during one of King's absences that resulted from

King's appointment as minister to France, Buchanan wrote to a Mrs.

Roosevelt, "I am now 'solitary and alone', having no companion in the

house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not

succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to

be alone, and [I] should not be astonished to find myself married to

some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for

me when I am well, and not expect from me any very ardent or romantic

affection." The only President never to marry, Buchanan turned to Harriet

Lane, an orphaned niece whom he had earlier adopted, to act as his

official hostess.