<Back to Index>

- Seismologist Charles Francis Richter, 1900

- Playwright William Shakespeare, 1564

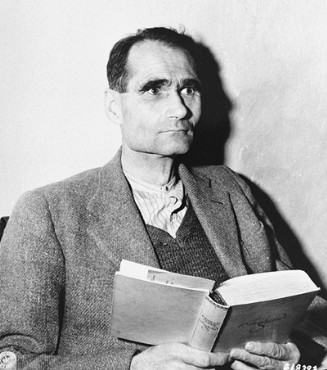

- Deputy Führer Rudolf Walter Richard Hess, 1894

PAGE SPONSOR

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (written Heß in German) (26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a prominent figure in Nazi Germany, acting as Adolf Hitler's Deputy in the Nazi Party. On the eve of war with the Soviet Union, he flew solo to Scotland in an attempt to negotiate peace with the United Kingdom, but instead was arrested. He was tried at Nuremberg and sentenced to life in prison at Spandau Prison, Berlin, where he died in 1987.

Hess'

attempt to negotiate peace and subsequent lifelong imprisonment have

given rise to many theories about his motivation for flying to

Scotland, and conspiracy

theories about why

he remained imprisoned alone at Spandau, long after all other convicts

had been released. On 27 September and 28 September 2007, numerous

British news services published descriptions of conflict between his Western and Soviet captors over his treatment

and how the Soviet captors were steadfast in denying repeated

entreaties for his release on humanitarian grounds during his last

years. Hess has

become a figure of veneration among neo-Nazis. His son Wolf

Rüdiger Hess became

a prominent rightist and claimed that his father was murdered. Hess was

born in Alexandria, Egypt,

the

eldest of four children, to Fritz H. Hess, a German Lutheran importer/exporter from Bavaria and Klara Münch. The

family moved to Germany in 1908, where Rudolf was subsequently enrolled

in boarding school. Although he expressed interest in being an astronomer,

his

father convinced him to study business in Switzerland. At the

outbreak of World

War

I he enlisted

in the 7th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment, became an infantryman and

was awarded the Iron

Cross, second class. After being wounded on numerous occasions -

including a chest wound severe enough to prevent his return to the

front as an infantryman - he transferred to the Imperial Air Corps

(after being rejected once). He then took aeronautical training and

served in an operational squadron, Jasta 35b (Bavarian), with the rank

of lieutenant from 16 October 1918. He

had no victories. On 20

December 1927 Hess married 27-year-old Ilse Pröhl (22 June 1900 –

7 September 1995) from Hannover.

Together

they had a son, Wolf

Rüdiger

Hess (18

November 1937 – 24 October 2001). After the

war Hess went to Munich and joined the Freikorps and Eiserne

Faust (Iron

Fist). He also joined the Thule

Society, a völkisch occult-mystical organization. Hess enrolled in the University

of

Munich where he

studied political

science, history, economics, and geopolitics under Professor Karl

Haushofer. After hearing Hitler speak in May 1920, he became

completely devoted to him. Ilse Hess’s description of the results of

her husband’s first encounter with Hitler is reminiscent of a religious

conversion. For

commanding an SA battalion during the Beer

Hall

Putsch, Hess served seven-and-a-half months in Landsberg

Prison. Acting as Hitler's private secretary, he transcribed and

partially edited Hitler's book Mein

Kampf. He also

introduced Hitler at party rallies. Eventually, Hess became the

third most powerful man in Germany, behind Hitler and Hermann

Göring. Soon

after Hitler assumed dictatorial powers, Hess was named "Deputy to the

Fuhrer." Hess had a privileged position as Hitler's deputy in the early

years of the Nazi movement and in the early years of the Third Reich.

For instance, he had the power to take "merciless action" against any

defendant who he thought got off too lightly — especially in cases of

those found guilty of attacking the party, Hitler or the state. Hess

also played a prominent part in the creation of the Nuremberg

Laws in 1935.

Hitler biographer John

Toland described

Hess' political insight and abilities as somewhat limited. Hess was

increasingly marginalized throughout the 1930s as foreign policy took

greater prominence. His alienation increased during the early years of

the war, as attention and glory were focused on military leaders, along

with Göring, Joseph

Goebbels and Heinrich

Himmler. Hess worshipped Hitler more than did Göring, Goebbels

and Himmler, but he was not nakedly ambitious and did not crave power in the same manner the others did. However, as the Deputy

Fuhrer, Hess held as much power (If not more than) the other Nazi party leaders

under Hitler. He controlled who could get an audience with the

Fuhrer, as well as passing and vetoing proposed bills, and managing party activities. On the

day Germany invaded Poland and launched World War II, Hitler announced

that should anything happen to both him and Göring, Hess would be

next in the line of succession. Hess

ordered a mapping of all the ley

lines in the Third

Reich. Like Goebbels,

Hess

was privately distressed by the war with the United Kingdom

because he, like almost all other Nazis, hoped that Britain would

accept Germany as an ally. Hess may have hoped to score a diplomatic

victory by sealing a peace between the Third

Reich and Britain, e.g., by implementing the

behind-the-scenes move of the Haushofers in

Nazi

Germany to contact Douglas

Douglas-Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton. On 10 May

1941, at about 6:00 P.M., Hess took off from Augsburg in a Messerschmitt

Bf

110, and Hitler ordered the General

of

the Fighter Arm to

stop Hess (squadron leaders were ordered to scramble only one or two

fighters since Hess' particular aircraft could not be distinguished

from others). Hess parachuted over Renfrewshire,

Scotland,

on 10 May and landed (breaking his ankle) at Floors Farm near Eaglesham. In

a newsreel clip, farmhand David McLean

claims to have arrested Hess with his pitchfork. It

appears that Hess believed the Duke of Hamilton to be an opponent of Winston

Churchill, whom he held responsible for the outbreak of the war.

His proposal of peace included returning all the western European

countries conquered by Germany to their own national governments, but

German police would remain in position. Germany would also pay back the

cost of rebuilding these countries. In return, Britain would have to

support the war against the Soviet

Union. Churchill

sent Hess initially to the Tower

of

London, making Hess the last, in the long line of prominent

political prisoners, to be held in the fortress. The Prime Minister gave

orders that he was to be strictly isolated but treated with dignity. He remained in the Tower

until 20 May 1941. After

being held in the Maryhill army barracks, he was

transferred to Mytchett Place near Aldershot.

The

house was fitted with microphones and sound recording equipment. Frank

Foley and two other

MI6 officers were given the job of debriefing Hess — or "Jonathan", as

he was now known. Churchill's instructions were that Hess should be

strictly isolated, and that every effort should be taken to get any

information out of him that might be useful. British Intelligence

personnel, Ian

Fleming in

particular, proposed that Aleister

Crowley should

question Hess on Nazi interest in the occult. Hess

became increasingly agitated as his conviction grew that he would be murdered.

Mealtimes

were difficult, since Hess suspected that his food might be

poisoned, and the MI6 officers had to exchange their food with his to

reassure him. Gradually, their conviction grew that Hess was insane. Hess was

interviewed by psychiatrist John

Rawlings

Rees who

had worked at the Tavistock

Clinic prior to

becoming a Brigadier in the Army. Rees

concluded that he was not insane, but certainly mentally ill and

suffering from depression — probably due to the

failure of his mission. Hess' diaries from his

imprisonment in Britain after 1941 make many references to visits from

Rees, whom he did not like and accused of poisoning him and "mesmerizing"

him.

Rees took part in the Nuremberg

Trials of 1945. Taken by

surprise, Hitler had Hess' staff arrested. Questioning revealed that

Hess was not motivated by disloyalty, but had simply cracked under the

strain of the war. The official statement from the German government

said that Hess had fallen victim to hallucinations brought on by old

injuries from the previous war. Hitler

also stripped Hess of all of his party and state offices, and privately

ordered him shot on sight if he ever returned to Germany. However, Hitler did grant Hess' wife a pension. Martin

Bormann succeeded

Hess as deputy under a newly-created title. Hess was

detained by the British for the remainder of the war, for most of the

time at Maindiff Court Military Hospital in Abergavenny,

Wales, where he would often be taken to the White Castle on Offa's Dyke

Path. It was rumoured that he was befriended by the local populace. He was also held just

outside Lostwithiel in Cornwall for six months, in a large property

aptly named 'Castle'. He then became a defendant at the Nuremberg

Trials of the

International Military Tribunal, where, in 1946, he was found guilty on

two of four counts: crimes against peace (planning and preparation of

aggressive war) and conspiracy with other German leaders

to commit crimes. He was found not guilty of war

crimes or crimes

against

humanity. He was given a life sentence. Some of

his last words before the tribunal were, "I regret nothing." For

decades he was addressed only as prisoner

number

seven. Throughout the investigations prior to trial Hess

claimed amnesia,

insisting

that he had no memory of his role in the Nazi Party. He went on to

pretend not to recognise even Hermann Göring — who was as

convinced as the psychiatric team that Hess had lost his mind. Hess

then addressed the court, several weeks into hearing evidence, to

announce that his memory had returned — thereby destroying his defence

of diminished responsibility. He later confessed to having enjoyed

pulling the wool over the eyes of the investigative psychiatric team.

Hess was

considered to be the most mentally unstable of all the defendants. He

would be seen talking to himself in court, counting on his fingers,

laughing for no obvious reason. Such behaviour was a source of great

annoyance to Göring, who made clear his desire to be seated apart

from him. The request was denied. Following

the release in 1966 of Baldur

von

Schirach and Albert

Speer, Hess was the sole remaining inmate of Spandau

Prison, partly at the insistence of the Soviets. Guards reportedly

said he degenerated mentally and lost most of his memory. For two

decades, his main companion was warden Eugene

K.

Bird, with whom he formed a close friendship. Bird wrote a 1974

book titled The

Loneliest Man in the World: The Inside Story of the 30-Year

Imprisonment of Rudolf Hess about

his

relationship with Hess. Frank

Keller who was a former guard at Spandau prison said that "Hess would

march by himself in the jail courtyard every day". Keller also said

that Hess would march in the classic Nazi heel-to-toe style. Many

historians and legal commentators have expressed opinions that his long

imprisonment was an injustice. In his book, The Second World War

Part III, Winston

Churchill wrote, The

Hess

flight raised suspicions with Josef Stalin, leader of the USSR, that

secret discussions were under way between Great Britain and Germany to

attack the Soviet Union. Later, in a meeting with Stalin, Churchill

would address the topic and find Stalin still believed secret

agreements were discussed with Hess. "When I make a statement of facts

within my knowledge I expect it to be accepted," Churchill responded to

Stalin, again denying that the incident resulted in any communications

with Nazi Germany. In the

early 1970s, the U.S., British and French

governments had

approached the Soviet government to propose that Hess be released on

humanitarian grounds due to his age. The Soviet official response was

apparently to reject these attempts and reportedly "refused to consider

any reduction in Hess' life sentence." U.S.

President Richard

Nixon was in favour

of releasing Hess and stated that the U.S., Britain and France should

continue to entreat the Soviet Union for his release. In 1977,

Britain's chief prosecutor at Nuremberg, Sir Hartley

Shawcross, characterised Hess' continued imprisonment as a "scandal". In 1987, the new Soviet

leadership agreed that Hess should be set free on humanitarian grounds.

Hess was aware of that decision. On 17

August 1987, Hess died while under Four

Power imprisonment

at Spandau

Prison in West

Berlin, at the age of 93. He was found in a summer house in a

garden located in a secure area of the prison with an electrical cord

wrapped around his neck. His death was ruled a suicide by self-asphyxiation. He

was buried at Wunsiedel in a Hess family grave plot

sold to his family by the Vetters of the Sechsämtertropfen bitter

liquor company of Wunsiedel. Spandau Prison was subsequently demolished

to prevent it from becoming a shrine. After

Hess' death, neo-Nazis from Germany and the rest

of Europe gathered in Wunsiedel for

a memorial march and

similar demonstrations took place every year around the anniversary of

Hess' death. These gatherings were banned from 1991 to 2000 and

neo-Nazis tried to assemble in other cities and countries (such as the

Netherlands and Denmark). Demonstrations in Wunsiedel were again

legalised in 2001. Over 5,000 neo-Nazis marched in 2003, with over

9,000 in 2004, marking some of the biggest Nazi demonstrations in

Germany since 1945. After stricter German legislation regarding

demonstrations by neo-Nazis was enacted in March 2005, the

demonstrations were banned again. At the

time of his death, he was the last surviving member of Hitler's

cabinet.