April 29, 2011

<Back to Index>

This page is sponsored by:

PAGE SPONSOR |

Hirohito,

also

known as Emperor

Shōwa,

(April

29, 1901 – January 7, 1989) was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the

traditional order, reigning from December 25, 1926, until his death in

1989. Although better known outside of Japan by his personal name

Hirohito, in Japan he is now referred to exclusively by his posthumous

name Emperor Shōwa.

The word Shōwa is the name

of

the era that

corresponded with the Emperor's reign, and was made the Emperor's own

name upon his death.

At the

start of his reign, Japan was still a fairly rural country with a

limited industrial base. He

was

the supreme ruler during Japan's militarization and involvement in World

War

II. After

World War II, his followers were prosecuted for war crimes, but he was

not prosecuted. During the postwar

period, he became the “symbol” of the new state.

Born in

the Aoyama

Palace in Tokyo,

Prince

Hirohito was the first son of Crown

Prince Yoshihito

(the future Emperor

Taishō) and Crown Princess Sadako (the future Empress

Teimei). His childhood title was

Prince Michi.

He

became heir apparent upon the death of his grandfather, Emperor

Meiji, on July 30, 1912. He was formally proclaimed as Crown Prince

and heir

apparent in

November 2, 1916; but an investiture ceremony was not strictly

necessary to confirm this status as heir to the throne.

Prince

Hirohito attended the YMCA of Gakushuin Peers' School from 1908 to

1914 and then a special institute for the crown prince

(Tōgū-gogakumonsho) from 1914 to 1921.

In 1921,

Prince Hirohito took a six month tour of Europe,

including

the United

Kingdom, France, Italy,

the Netherlands and Belgium,

becoming the first Japanese crown prince to travel abroad. After his

return to Japan, he became Regent of Japan on November 29, 1921, in

place of his ailing father who was affected by a mental illness. During

Prince Hirohito's regency, a number of important events occurred:

In the Four-Power

Treaty on Insular

Possessions signed on December 13, 1921, Japan, the United States,

Britain and France agreed to recognize the status quo in the Pacific,

and Japan and Britain agreed to terminate formally the Anglo-Japanese

Alliance. The Washington

Naval Treaty was

signed on February 6, 1922. Japan completed withdrawal of troops from

the Siberian

Intervention on

August 28, 1922. The Great Kantō

earthquake devastated

Tokyo

on September 1, 1923. The General

Election

Law was

passed on May 5, 1925, giving all men above age 25 the right to vote.

Prince

Hirohito married his distant cousin Princess Nagako Kuni (the future Empress

Kōjun), the eldest daughter of Prince

Kuni

Kuniyoshi, on January 26, 1924. They had two sons and five

daughters. The

daughters

who lived to adulthood left the imperial family as a result

of the American reforms of the Japanese imperial household in October

1947 (in the case of Princess Higashikuni) or under the terms of the Imperial Household

Law at

the moment of their subsequent marriages (in the cases of Princesses

Kazuko, Atsuko, and Takako).

On

December 25, 1926, Hirohito assumed the throne upon the death of his

father Yoshihito; and the Crown Prince was said to have received the succession (senso). The Taishō

era ceased at once

and a new era, the Shōwa

era (Enlightened Peace), was proclaimed. The deceased Emperor was

posthumously renamed Emperor

Taishō a few days

later. Following Japanese custom, the new Emperor was never

referred to by his

given name, but rather was referred to simply as "His Majesty the Emperor",

which

may be shortened to "His

Majesty".

In

writing, the Emperor was also referred to formally as "The Reigning

Emperor".

In

November 1928, the Emperor's ascension was confirmed in ceremonies (sokui) which are conventionally

identified as "enthronement" and "coronation" (Shōwa no tairei-shiki);

but

this formal event would have been more accurately described as a

public confirmation that his Imperial Majesty possesses the Japanese Imperial

Regalia, also called the Three

Sacred

Treasures, which have been handed down through centuries.

The first

part of Hirohito's reign as sovereign took place against a background of financial

crisis and

increasing military power within the government, through both legal and

extralegal means. The Imperial

Japanese

Army and Imperial

Japanese

Navy had

held veto power over the formation of

cabinets since 1900, and between 1921 and 1944 there were no fewer than

64 incidents of political violence.

Hirohito

narrowly missed assassination by a hand

grenade thrown by a Korean

independence

activist, Lee

Bong-chang in Tokyo

on January 9, 1932, in the Sakuradamon

Incident. Another

notable case was the assassination of moderate Prime

Minister Inukai

Tsuyoshi in 1932,

which marked the end of civilian

control

of the military. This was followed by an attempted military

coup in February

1936, the February

26

incident, mounted by junior Army officers of the Kōdōha faction who had the

sympathy of many high-ranking officers including Prince

Chichibu (Yasuhito)

one of the Emperor's brothers. This revolt was occasioned by a loss of

ground by the militarist faction in Diet elections. The coup

resulted in the murder of a number of high government and Army

officials. When Chief Aide-de-camp Shigeru

Honjō informed him

of the revolt, the Emperor immediately ordered that it be put down and

referred to the officers as "rebels" (bōto). Shortly thereafter,

he ordered Army Minister Yoshiyuki

Kawashima to

suppress the rebellion within the hour, and he asked reports from Honjō

every thirty minutes. The next day, when told by Honjō that little

progress was being made by the high command in quashing the rebels, the

Emperor told him "I Myself, will lead the Konoe

Division and subdue

them." The rebellion was suppressed following his orders on February

29.

Prior to World

War

II, Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and the rest of China in 1937 (the Second

Sino-Japanese

War). Primary sources reveal that Emperor Shōwa never

really had any objection to the invasion of China in 1937,

which

was recommended to him by his chiefs of staff and prime minister Fumimaro

Konoe. His main concern seems to have been the possibility of an

attack by the Soviets in the north. His questions to his chief of staff, Prince

Kan'in, and minister of the army, Hajime

Sugiyama, were mostly about the time it could take to crush the

Chinese resistance. According

to Akira Fujiwara, the Emperor personally ratified the proposal by the

Japanese Army to remove the constraints of international law on the

treatment of Chinese prisoners on August 5. Moreover, the works of Yoshiaki

Yoshimi and Seiya

Matsuno show that the Emperor authorized, by specific orders

(rinsanmei), the use of chemical weapons against the Chinese. During the invasion of Wuhan,

from

August to October 1938, the Emperor authorized the use of toxic

gas on 375 separate occasions, despite the resolution adopted by the League

of

Nations on May

14 condemning the use of toxic gas by the Japanese Army.

During World

War

II, ostensibly under Emperor Hirohito's leadership, Japan formed alliances with Nazi

Germany and Fascist

Italy, forming the Axis

Powers. In July 1939, the Emperor quarreled with one of his

brothers, Prince

Chichibu, who was visiting him three times a week to support the

treaty, and reprimanded the army minister Seishiro

Itagaki. However, after the success

of the Wehrmacht in Europe, the Emperor consented to the alliance. On

September 4, 1941, the Japanese Cabinet met to consider war plans

prepared by Imperial General Headquarters, and decided that:

| “ |

Our Empire, for

the purpose of self-defense and self-preservation, will complete

preparations for war ... [and is] ... resolved to go to war with the United

States, Great

Britain, and the French if necessary. Our Empire

will concurrently take all possible diplomatic measures

vis-à-vis the United States and Great Britain, and thereby

endeavor to obtain our objectives ... In the event that there is no

prospect of our demands being met by the first ten days of October

through the diplomatic negotiations mentioned above, we will

immediately decide to commence hostilities against the United States,

Britain and the French. |

” |

The

"objectives" to be obtained were clearly defined: a free hand to

continue with the conquest of China and Southeast

Asia, no increase in US or British military forces in the region,

and cooperation by the West "in the acquisition of goods needed by our

Empire."

On

September 5, Prime Minister Konoe informally submitted a draft of the

decision to the Emperor, just one day in advance of the Imperial

Conference at which it would be formally implemented. On this evening,

Emperor Shōwa had a meeting with the chief of staff of the army,

Sugiyama, chief of staff of the navy, Osami

Nagano, and Prime Minister Konoe. The Emperor questioned Sugiyama

about the chances of success of an open war with the Occident. As

Sugiyama answered positively, the Emperor scolded him:

| “ |

—At the time of

the China

incident, the army told me that we could make Chiang surrender after three

months but you still can't beat him even today! Sugiyama, you were

minister at the time.

—China is a vast area with many ways in and ways out, and we met

unexpectedly big difficulties.

—You say the interior of China is huge; isn't the Pacific Ocean even

bigger than China? Didn't I caution you each time about those matters?

Sugiyama, are you lying to me? |

” |

Chief

of

Naval General Staff Admiral Nagano, a former Navy Minister and vastly

experienced, later told a trusted colleague, "I have never seen the

Emperor reprimand us in such a manner, his face turning red and raising

his voice." According

to the traditional view, Emperor Shōwa was deeply concerned by the

decision to place "war preparations first and diplomatic negotiations

second," and he announced his intention to break with tradition. At the

Imperial Conference on the following day, the Emperor directly

questioned the chiefs of the Army and Navy general staffs, which was

quite an unprecedented action. Nevertheless,

all

speakers at the Imperial Conference were united in favor of war

rather than diplomacy. Baron Yoshimichi

Hara, President of the Imperial Council and the Emperor's

representative, then questioned them closely, producing replies to the

effect that war would only be considered as a last resort from some,

and silence from others. At this

point, the Emperor astonished all present by addressing the conference

personally, and in breaking the tradition of Imperial silence left his

advisors "struck with awe." (Prime Minister Konoe's description of the

event.) Emperor Shōwa stressed the need for peaceful resolution of

international problems, expressed regret at his ministers' failure to

respond to Baron Hara's probings, and recited a poem written by his

grandfather, Emperor Meiji which, he said, he had read "over and over

again":

| “ |

Across the

four seas, all are brothers.

In such a world why do the waves rage, the winds roar? |

” |

Recovering

from

their shock, the ministers hastened to express their profound wish

to explore all possible peaceful avenues. The Emperor's presentation was in line with his practical role as leader of the Shinto religion.

At this

time, Army Imperial Headquarters was continually communicating with the

Imperial household in detail about the military situation. On October

8, Sugiyama signed a 47-page report to the Emperor (sōjōan) outlining

in minute detail plans for the advance in Southeast Asia. During the

third week of October, Sugiyama gave the Emperor a 51-page document,

"Materials in Reply to the Throne," about the operational outlook for

the war. As war

preparations continued, Prime Minister Konoe found himself more and

more isolated and gave his resignation on October 16. He justified

himself to his chief cabinet secretary, Kenji Tomita :

| “ |

Of course His

Majesty is a pacifist, and there is no doubt he wished to avoid war.

When I told him that to initiate war was a mistake, he agreed. But the

next day, he would tell me: "You were worried about it yesterday, but

you do not have to worry so much." Thus, gradually, he began to lead

toward war. And the next time I met him, he leaned even more toward. In

short, I felt the Emperor was telling me: my prime minister does not

understand military matters, I know much more. In short, the Emperor

had absorbed the view of the army and navy high commands. |

” |

The army

and the navy recommended the candidacy of Prince

Higashikuni, one of the Emperor's uncles. According to the Shōwa

"Monologue," written after the war, the Emperor then said that if the

war were to begin while a member of the imperial house was prime

minister, the imperial house would have to carry the responsibility and

he was opposed to this. Instead,

the Emperor chose the hard-line General Hideki

Tōjō, who was known for his devotion to the imperial institution,

and asked him to make a policy review of what had been sanctioned by

the imperial conferences. On November 2, Tōjō, Sugiyama and Nagano

reported to the Emperor that the review of eleven points had been in

vain. Emperor Shōwa gave his consent to the war and then asked: "Are

you going to provide justification for the war?"

On

November 3, Nagano explained in detail the Pearl Harbor attack plan to

the Emperor. On November 5, Emperor

Shōwa approved in imperial conference the operations plan for a war

against the Occident and had many meetings with the military and Tōjō

until the end of the month. On December 1, an imperial conference

sanctioned the "War against the United States, United Kingdom and the

Kingdom of the Netherlands." On December 8 (December 7 in Hawaii) 1941,

in simultaneous attacks, Japanese forces struck at the US Fleet in Pearl

Harbor and began

the invasion of Malaysia.

With the

nation fully committed to the war, Emperor Shōwa took a keen interest

in military progress and sought to boost morale. According to Akira

Yamada and Akira Fujiwara, the Emperor made major interventions in some

military operations. For example, he pressed Sugiyama four times, on

January 13 and 21 and February 9 and 26, to increase troop strength and

launch an attack on Bataan.

On

February 9, March 19 and May 29, the Emperor ordered the Army Chief

of staff to examine the possibilities for an attack on Chungking,

which

led to Operation

Gogo.

As

the

tide of war gradually began to turn (around late 1942 and early 1943),

some people argue that the flow of information to the palace gradually

began to bear less and less relation to reality, while others suggest

that the Emperor worked closely with Prime Minister Tōjō, continued to

be well and accurately briefed by the military, and knew Japan's

military position precisely right up to the point of surrender. The

chief of staff of the General Affairs section of the Prime Minister's

office, Shuichi Inada, remarked to Tōjō's private secretary, Sadao

Akamatsu:

| “ |

There has never

been a cabinet in which the prime minister, and all the ministers,

reported so often to the throne. In order to effect the essence of

genuine direct imperial rule and to relieve the concerns of the

Emperor, the ministers reported to the throne matters within the scope

of their responsibilities as per the prime minister's directives... In

times of intense activities, typed drafts were presented to the Emperor

with corrections in red. First draft, second draft, final draft and so

forth, came as deliberations progressed one after the other and were

sanctioned accordingly by the Emperor. |

” |

In the

first six months of war, all the major engagements had been victories.

As the tide turned in the summer of 1942 with the battle

of

Midway and the

landing of the American forces on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August, the Emperor

recognized the potential danger and pushed the navy and the army for

greater efforts. In September 1942, Emperor Hirohito signed the

Imperial Rescript condemning to death American Fliers: Lieutenants Dean

E. Hallmark and William G. Farrow and Corporal Harold A. Spatz and

commuting to life sentences: Lieutenants Robert

J.

Meder, Chase

Nielsen, Robert L. Hite and George Barr and Corporal Jacob

DeShazer. When informed in August 1943 by Sugiyama that the American advance

through the Solomon

Islands could

not

be stopped, the Emperor asked his chief of staff to consider other

places to attack : "When and where on are you ever going to put up

a good fight? And when are you ever going to fight a decisive battle?" On August 24, the Emperor

reprimanded Nagano and on September 11, he ordered Sugiyama to work

with the Navy to implement better military preparation and give

adequate supply to soldiers fighting in Rabaul.

Throughout

the

following years, the sequence of drawn and then decisively lost

engagements was reported to the public as a series of great victories.

Only gradually did it become apparent to the people in the home islands

that the situation was very grim. U.S. air raids on the cities of Japan

starting in 1944 made a mockery of the unending tales of victory. Later

that year, with the downfall of Hideki Tōjō's government, two other

prime ministers were appointed to continue the war effort, Kuniaki

Koiso and Kantaro

Suzuki — each with the formal approval of the Emperor. Both were

unsuccessful and Japan was nearing defeat.

As the

tide of war turned against the Japanese, Hirohito personally found the

threat of defection of Japanese civilians disturbing because there was

a risk that live civilians would be surprised by generous U.S.

treatment. Native Japanese

sympathizers would hand the Americans a powerful propaganda weapon to

subvert the "fighting spirit" of Japan in radio broadcasts. At the end

of June 1944 during the Battle

of

Saipan, Hirohito sent out the first imperial order encouraging

all Japanese civilians to commit suicide rather than be captured or

taken prisoner. The

Imperial order authorized Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu

Saito, the commander of Saipan,

to

promise civilians who died there an equal spiritual status in the

afterlife with those of soldiers perishing in combat. General Tojo intercepted the order on 30

June and delayed its sending, but it was issued anyway the next day. By

the time the Marines advanced on the north tip of the island, from 8

July–12, most of the damage had been done. Over 10,000 Japanese

civilians committed suicide in the last days of the battle to take the

offered privileged place in the afterlife, some jumping from "Suicide

Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff".

In early

1945, in the wake of the loss of Leyte,

Emperor

Shōwa began a series of individual meetings with senior

government officials to consider the progress of the war. All but

ex-Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe advised continuing the war. Konoe

feared a communist revolution even more than

defeat in war and urged a negotiated surrender. In February 1945,

during the first private audience with the Emperor which he had been

allowed in three years, Konoe advised Hirohito to

begin negotiations to end World

War

II. According to Grand Chamberlain Hisanori

Fujita, the Emperor, still looking for a tennozan (a great victory) in order

to provide a stronger bargaining position, firmly rejected Konoe's

recommendation. With each

passing week a great victory became less likely. In April the Soviet

Union issued notice

that it would not renew its neutrality agreement. Japan's ally Germany surrendered in early May

1945. In June, the cabinet reassessed the war strategy, only to decide

more firmly than ever on a fight to the last man. This strategy was

officially affirmed at a brief Imperial Council meeting, at which, as

was normal, the Emperor did not speak.

The

following day, Lord

Keeper

of the Privy Seal Kōichi

Kido prepared

a

draft document which summarized the hopeless military situation and

proposed a negotiated settlement. According to some commentators, the Emperor privately

approved of it and authorized Kido to circulate it discreetly amongst

less hawkish cabinet members; others suggest that the Emperor was

indecisive, and that the delay cost many tens of thousands of Japanese

and Allied lives. Extremists in Japan were also calling for a

death-before-dishonor mass suicide, modeled on the "47

Ronin"

incident. By mid-June 1945, the cabinet had agreed to

approach the Soviet Union to act as a mediator for a negotiated

surrender, but not before Japan's bargaining position had been improved

by repulse of the anticipated Allied invasion of mainland Japan.

On June

22, the Emperor met his ministers, saying "I desire that concrete plans

to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and

that efforts be made to implement them." The attempt to negotiate a

peace via the Soviet Union came to nothing. There was always the threat

that extremists would carry out a coup or foment other violence. On

July 26, 1945, the Allies issued the Potsdam

Declaration demanding unconditional

surrender. The Japanese government council, the Big Six, considered

that option and recommended to the Emperor that it be accepted only if

one to four conditions were agreed, including a guarantee of the

Emperor's continued position in Japanese society. The Emperor decided not to surrender.

On August

9, 1945, following the atomic

bombings

of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and

the Soviet declaration

of war, Emperor Shōwa told Kido to "quickly control the situation"

because "the Soviet Union has declared war and today began hostilities

against us." On August 10, the cabinet drafted an "Imperial

Rescript

ending the War" following the Emperor's indications that

the declaration did not compromise any demand which prejudiced the

prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler.

On August

12, 1945, the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to

surrender. One of his uncles, Prince

Asaka, asked whether the war would be continued if the kokutai (national polity) could not

be preserved. The Emperor simply replied "of course." On August 14, the Suzuki government notified the Allies that it had accepted the Potsdam

Declaration. On August 15, a recording of the Emperor's surrender

speech was

broadcast over the radio (the first time the Emperor was heard on the

radio by the Japanese people) signifying the unconditional surrender of

Japan's military forces (known as Gyokuon-hōsō). Objecting

to the surrender, die-hard army fanatics attempted a coup

d'état by

conducting a full military assault and takeover of the Imperial Palace.

The physical recording of the surrender speech was hidden and preserved

overnight, and the coup was quickly crushed on the Emperor's order. The

surrender speech noted that "the war situation has developed not

necessarily to Japan's advantage" and ordered the Japanese to "endure

the unendurable" in surrender. It was the first time the public had

heard the Emperor's voice. The speech, using formal, archaic Japanese

was not readily understood by many commoners. According to historian

Richard Storry in A

History of Modern Japan, the Emperor typically used "a form of

language familiar only to the well-educated" and to the more traditional samurai families.

Many

historians see Emperor Shōwa as responsible for the

atrocities committed

by

the imperial forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War and in World War

II and feel that he, some members of the imperial family such as his

brother Prince

Chichibu, his cousins Prince

Takeda and Prince

Fushimi, and his uncles Prince

Kan'in, Prince

Asaka, and Prince

Higashikuni, should have been tried for war

crimes. Because of this perception

of responsibility for war crimes and lack of accountability, many

inhabitants of countries conquered by Japan, as well as others in

nations that fought Japan, retain a hostile attitude towards the Japanese

imperial

family. The issue

of Hirohito's responsibility for war crimes is a debate regarding how

much real control the Emperor had over the Japanese military during the

two wars. Officially, the imperial constitution, adopted under Emperor

Meiji, gave full power to the Emperor. Article 4 prescribed that, "The

Emperor

is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of

sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the

present Constitution," while, according to article 6, "The

Emperor gives sanction to laws and orders them to be promulgated and

executed," and article 11, "The

Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and the Navy." The Emperor was thus the

leader of the Imperial

General

Headquarters.

In 1971,

David Bergamini showed how primary sources, such as the "Sugiyama memo" and the diaries of Kido and Konoe,

describe

in detail the informal meetings Emperor Shōwa had with his

chiefs of staff and ministers. Bergamini concluded that the Emperor was

kept informed of all main military operations and that he frequently

questioned his senior staff and asked for changes. Historians

such

as Herbert

Bix, Akira

Fujiwara, Peter

Wetzler, and Akira

Yamada assert that

the post-war view focusing on imperial conferences misses the

importance of numerous "behind the chrysanthemum curtain" meetings

where the real decisions were made between the Emperor, his chiefs of

staff, and the cabinet. Historians such as Fujiwara and Wetzler, based on the primary

sources and the monumental work of Shirō

Hara, have produced evidence suggesting that the Emperor worked through intermediaries to exercise a

great deal of control over the military and was neither bellicose nor a

pacifist, but an opportunist who governed in a pluralistic

decision-making process. American historian Herbert

Bix argues that Emperor Shōwa might have been the prime mover of

most of the events of the two wars.

The view

promoted by both the Japanese Imperial Palace and the American

occupation forces immediately after World War II had Emperor Shōwa as a

powerless figurehead behaving strictly according

to protocol, while remaining at a distance from the decision-making

processes. This view was endorsed by Prime Minister Noboru

Takeshita in a

speech on the day of Hirohito's death, in which Takeshita asserted that

the war had broken

out against [Hirohito's] wishes. Takeshita's

statement

provoked outrage in nations in East Asia and Commonwealth

nations such as the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. For Fujiwara, however, "the

thesis that the Emperor, as an organ of responsibility, could not

reverse cabinet decision, is a myth fabricated after the war." In Japan,

debate over the Emperor's responsibility was taboo while he was still

alive. After his death, however, debate began to surface over the

extent of his involvement and thus his culpability. In the

years immediately after Hirohito's death, the debate in Japan was

fierce. Susan Chira reported that, "Scholars who have spoken out

against the late Emperor have received threatening phone calls from

Japan's extremist right wing." One example of actual

violence occurred in 1990 when the mayor of Nagasaki, Hitoshi

Motoshima, was shot and critically wounded by a member of the

ultranationalist group, Seikijuku; Motoshima

managed to recover from the attack. In 1989, Motoshima had

broken what was characterized as "one of [Japan's] most sensitive

taboos" by asserting that Emperor Hirohito bore some responsibility for

World War II. Kentaro

Awaya argues that post-war Japanese public opinion supporting

protection of the Emperor was influenced by US propaganda promoting the

view that the Emperor together with the Japanese people had been fooled

by the military.

As the

Emperor chose his uncle Prince

Higashikuni as

prime minister to assist the occupation, there were attempts by

numerous leaders to have him put on trial for alleged war

crimes. Many members of the imperial family, such as Princes

Chichibu, Takamatsu and Higashikuni, pressured the Emperor to abdicate

so that one of the Princes could serve as regent until Crown Prince Akihito came of age. On February 27, 1946, the

emperor's youngest brother, Prince

Mikasa (Takahito),

even stood up in the privy council and indirectly urged the emperor to

step down and accept responsibility for Japan's defeat. According to

Minister of Welfare Ashida's diary, "Everyone seemed to ponder Mikasa's

words. Never have I seen His Majesty's face so pale."

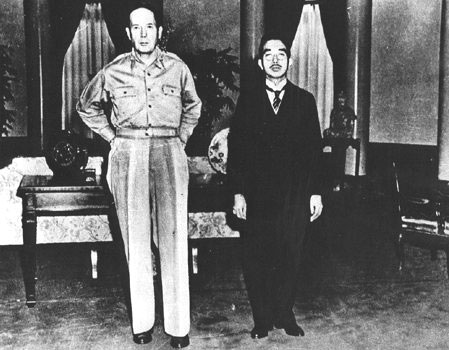

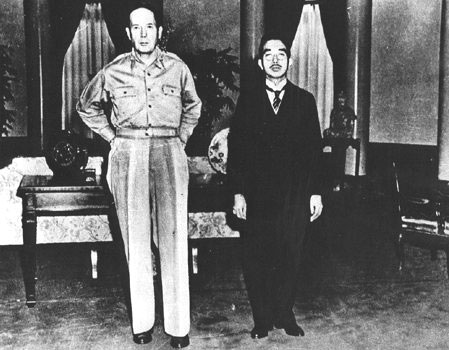

U.S.

General Douglas

MacArthur insisted

that Emperor Shōwa retain the throne. MacArthur saw the emperor as a

symbol of the continuity and cohesion of the Japanese people. Many

historians criticize the decision to exonerate the Emperor and all

members of the imperial family who were implicated in the war, such as Prince

Chichibu, Prince

Asaka, Prince Higashikuni and Prince Hiroyasu

Fushimi, from criminal prosecutions. Before

the war crime trials actually convened, the SCAP,

the IPS,

and

Japanese officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the

Imperial family from being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of

the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the emperor. High

officials in court circles and the Japanese government collaborated

with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while

the individuals arrested as Class

A suspects and

incarcerated in Sugamo prison solemnly vowed to

protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war

responsibility. Thus, "months before the Tokyo

tribunal commenced,

MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate

responsibility for Pearl

Harbor to Hideki

Tōjō" by allowing "the major

criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the Emperor would

be spared from indictment." According

to John Dower,

"This successful campaign to absolve the Emperor of war responsibility

knew no bounds. Hirohito was not merely presented as being innocent of

any formal acts that might make him culpable to indictment as a war

criminal, he was turned into an almost saintly figure who did not even

bear moral responsibility for the war." According

to

Bix, "MacArthur's truly extraordinary measures to save Hirohito from

trial as a war criminal had a lasting and profoundly distorting impact

on Japanese understanding of the lost war."

Toward

the end of the occupation, Hirohito let it be known to SCAP that he was

prepared to apologize formally to U.S. Gen. MacArthur for Japan's

actions during World War II – including an apology for the

December 7, 1941 attack

on

Pearl Harbor. According

to Patrick

Lennox

Tierney, on the day the Emperor came to offer this apology,

MacArthur refused to admit him or acknowledge him. Tierney was an eye

witness because his office was on the fifth floor of the Dai-Ichi

Insurance

Building in

Tokyo, the same floor where MacArthur's suite was situated. Many years

later, Tierney made an effort to explain his understanding of the

significance of what he had personally witnessed: "Apology is a very

important thing in Japan." A pivotal moment passed.

Issues which might have been addressed were allowed to remain open, with consequences which have unfolded across decades.

The

Emperor was not put on trial, but he was forced to explicitly reject

the State

Shinto claim that the Emperor of Japan was an arahitogami,

i.e., an incarnate divinity. This was motivated by the fact that,

according to the Japanese

constitution

of 1889, the Emperor had a divine power over his

country, which was derived from the shinto belief

that

the Japanese Imperial Family was the offspring of the sun goddess Amaterasu. Hirohito

was however persistent in the idea that the emperor of Japan

should be considered a descendant of the gods. In December 1945 he told

his vice-grand chamberlain Michio

Kinoshita: "It is permissible to say that the idea that the

Japanese are descendants of the gods is a false conception; but it is

absolutely impermissible to call chimerical the idea that the emperor

is a descendant of the gods." In any case, the

"renunciation of divinity" was noted more by foreigners than by

Japanese, and seems to have been intended for the consumption of the

former. Although

the Emperor supposedly had repudiated claims to divine status, his

public position was deliberately left vague, partly because General

MacArthur thought him likely to be a useful partner to get the Japanese

to accept the occupation, and partly due to behind-the-scenes

maneuverings by Shigeru

Yoshida to thwart

attempts to cast him as a European-style monarch.

While

Emperor Shōwa was usually seen abroad as a head

of

state, there is still a broad dispute about whether he became a

common citizen or retained special status related to his religious

offices and participations in Shinto and Buddhist calendar rituals.

Many scholars claim that today's tennō (usually translated Emperor

of

Japan in

English) is not an emperor.

For the

rest of his life, Emperor Shōwa was an active figure in Japanese life,

and performed many of the duties commonly associated with a

constitutional head

of

state. The emperor and his family maintained a strong public

presence, often holding public walkabouts, and making public appearances on special events and ceremonies. Emperor

Shōwa also played an important role in rebuilding Japan's diplomatic

image, traveling abroad to meet with many foreign leaders, including

Queen Elizabeth

II (1971) and

President Gerald

Ford (1975).

The

emperor was deeply interested in and well-informed about marine

biology, and the Imperial

Palace contained a

laboratory from which the emperor published several papers in the field

under his personal name "Hirohito." His contributions included

the description of several dozen species of Hydrozoa new to science.

Emperor

Shōwa maintained an official boycott of the Yasukuni

Shrine after it was

revealed to him that Class-A war criminals had secretly been enshrined

after its post-war rededication. This boycott lasted from 1978 until

the time of his death. This boycott has been maintained by his son Akihito,

who

has also refused to attend Yasukuni. On July

20, 2006, Nihon

Keizai

Shimbun published

a

front page article about discovery of a memorandum detailing the

reason that the Emperor stopped visiting Yasukuni. The memorandum, kept

by former chief of Imperial Household

Agency Tomohiko Tomita, confirms for the first time that

the enshrinement of 14 Class

A

War Criminals in

Yasukuni was the reason for the boycott. Tomita recorded in detail the

contents of his conversations with the emperor in his diaries and

notebooks. According to the memorandum, in 1988, the emperor expressed

his strong displeasure at the decision made by Yasukuni Shrine to

include Class-A war criminals in the list of war dead honored there by

saying, "At some point, Class-A criminals became enshrined, including Matsuoka and Shiratori.

I

heard Tsukuba acted cautiously." Tsukuba is believed to refer to

Fujimaro Tsukuba, the former chief Yasukuni priest at the time, who

decided not to enshrine the war criminals despite having received in

1966 the list of war dead compiled by the government. "What's on the

mind of Matsudaira's son, who is the current head priest?" "Matsudaira

had a strong wish for peace, but the child didn't know the parent's

heart. That's why I have not visited the shrine since. This is my

heart." Matsudaira is believed to refer to Yoshitami Matsudaira, who

was the grand steward of the Imperial Household immediately after the

end of World War II. His son, Nagayoshi, succeeded Fujimaro Tsukuba as

the chief priest of Yasukuni and decided to enshrine the war criminals

in 1978. Nagayoshi Matsudaira died

in 2006, which some commentators have speculated is the reason for

release of the memo.

For

journalist Masanori Yamaguchi, who analyzed the "memo" and comments

made by the emperor in his first-ever press conference in 1975, the

emperor's evasive and opaque attitude about his own responsibility for

the war and the fact he said that the bombing of Hiroshima "could not

be helped", could mean that the emperor

was afraid that the enshrinement of the war criminals at Yasukuni would

reignite the debate over his own responsibility for the war.

Hirohito

met some American celebrities over the post-war years. In 1959, he sat

in the same room for a viewing of the classic film Ben Hur with the

film's star, Charlton Heston.

On

September 22, 1987, the Emperor underwent surgery on his pancreas after having digestive

problems for several months. The doctors discovered that he had duodenal

cancer. The emperor appeared to be making a full recovery for

several months after the surgery. About a year later, however, on

September 19, 1988, he collapsed in his palace, and his health worsened

over the next several months as he suffered from continuous internal

bleeding. On January 7, 1989, at 7:55 AM, the grand steward of Japan's

Imperial Household Agency, Shoichi Fujimori, officially announced the

death of Emperor Hirohito, and revealed details about his cancer for

the first time. The emperor was succeeded by his son, Akihito.

The

emperor's death ended the Shōwa

era. On the same day a new era began: the Heisei

era. From January 7 until January 31, the emperor's formal

appellation was "Taikō Tennō",

which

means the departed emperor. His definitive posthumous

name (Shōwa Tennō)

was determined on January 13 and formally released on January 31 by Toshiki

Kaifu, the prime minister.

On

February 24, Emperor Shōwa's state funeral was held, and unlike that of

his predecessor, it was formal but not conducted in a strictly Shinto manner. A large number of

world leaders attended the funeral, including U.S. President George

H.

W. Bush. Emperor Shōwa is buried in the Imperial mausoleum in Hachiōji,

alongside Emperor

Taishō, his father.

|