<Back to Index>

- Physicist Vikram Ambalal Sarabhai, 1919

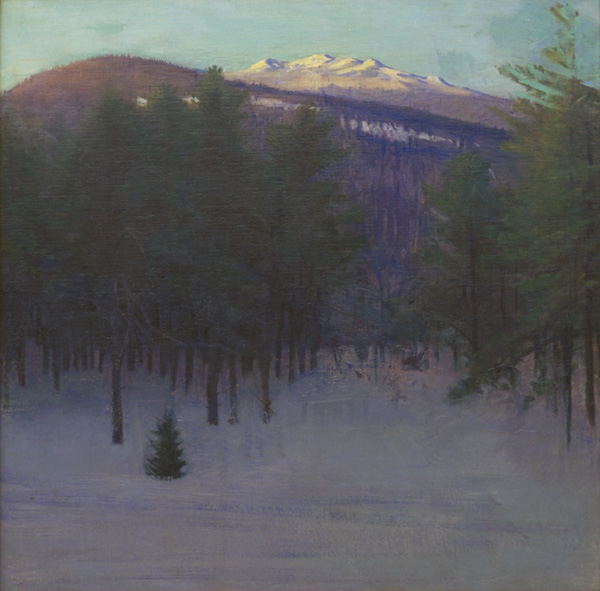

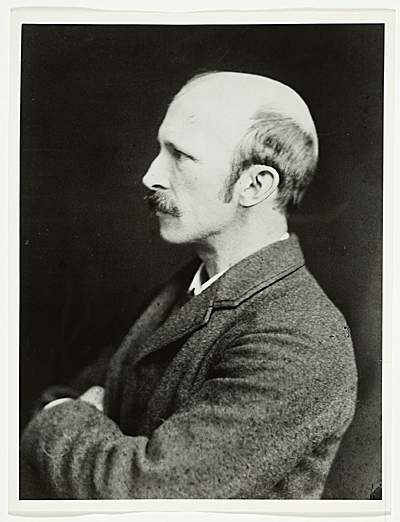

- Painter Abbott Handerson Thayer, 1849

- King of Denmark and Norway Christian III, 1503

PAGE SPONSOR

Abbott Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849 – May 29, 1921) was an American artist, naturalist and teacher. As a painter of portraits, figures, animals and landscapes, he enjoyed a certain prominence during his lifetime, as shown by the fact that his paintings are in the most important U.S. art collections. In the last third of his life, he worked together with his son, Gerald Handerson Thayer, on a major book about protective coloration in nature, titled Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom: An Exposition of the Laws of Disguise Through Color and Pattern; Being a Summary of Abbott H. Thayer’s Disclosures. First published by Macmillan in 1909, then reissued in 1918, it had a widespread impact on the use of military camouflage during World War I. He also influenced American art through his efforts as a teacher, taking on apprentices in his New Hampshire studio.

Thayer was born in Boston, Massachusetts. The son of a country doctor, he spent his childhood in rural New Hampshire, near Keene, at the foot of Mount Monadnock. In that rural setting, he became an amateur naturalist (in his own words, he was “bird crazy”), a hunter and a trapper. He studied Audubon's Birds of America on an almost daily basis, experimented with taxidermy, and made his first artworks: watercolor paintings of animals.

At age 18, he moved to Brooklyn, New York, to study painting at the Brooklyn Art School and the National Academy of Design. In 1875, having married Kate Bloede, he moved to Paris, where he studied for four years at the École des Beaux-Arts, with Henri Lehmann and Jean-Léon Gérôme, and where his closest friend became the American artist George de Forest Brush. Returning to New York, he set up his own portrait studio (which he shared with Daniel Chester French), became active in the Society of American Painters, and began to take in apprentices. Life

became all but unbearable for Thayer and his wife in the early 1880s,

when two of their small children died unexpectedly, just one year apart. Emotionally

devastated, they spent the next several years moving from place to

place, gradually severing their ties to New York. Although he was not

yet financially secure, Thayer's growing reputation led to more

portrait commissions than he could accept. Among his sitters were Mark Twain and Henry James, but the subjects of many of his paintings were the three remaining Thayer children, Mary, Gerald and Gladys. In 1898, Thayer visited St Ives, Cornwall and, carrying an introductory letter from C. Hart Merrian, the Chief of the US Biological Survey in Washington, D.C.,

applied to the lord of the Manor of St Ives and Treloyhan, Henry Arthur

Mornington Wellesley, the 3rd Earl Cowley, for permission to collect

specimens of birds from the cliffs at St Ives. In 1901, he and his wife

settled permanently in Dublin, New Hampshire,

where they had often vacationed and where Thayer had grown up. Soon

after, when her father died, Thayer’s wife lapsed into an irreversible

depression, which led to her confinement in an asylum, the decline of

her health, and eventual death, on May 3, 1891. Soon after, Thayer married their long-time friend, Emma Beach, whose father owned The New York Sun.

He and his second wife spent their remaining years in rural New

Hampshire, living a spartan existence and working productively.

Eccentric and opinionated, Thayer grew more so as he aged, and his

family's manner of living reflected his strongly held beliefs: the

Thayers typically slept outdoors year-round in order to enjoy the

benefits of fresh air, and the three children were never enrolled in school. The younger two, Gerald and Gladys, fully shared their father's enthusiasms, and became painters. Throughout

this latter part of his life, among Thayer’s Dublin neighbors was

George de Forest Brush, with whom (when they were not quarreling) he

collaborated on matters pertaining to camouflage.

It

is difficult to speak simply and conclusively about Thayer as an

artist. He was often described in first person accounts as eccentric

and mercurial, and there is a parallel contradictory mix of academic

tradition, spontaneity and improvisation in his artistic methods. For

example, he is largely known as a painter of “ideal figures,” in which

he portrayed women as embodiments of virtue, adorned in flowing white

tunics and equipped with feathered angel’s wings. At the same time, he

did this using methods that were surprisingly unorthodox, unfettered

and surprising, such as purposely mixing dirt into the paint, or (in

one instance at least) using a broom instead of a brush to lessen the

sense of rigidity in a newly finished, still wet painting. He survived

with the help of his patrons, among them the industrialist Charles Lang Freer. Some of his finest works are in the collections of the Freer Gallery of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Academy of Design, National Museum of American Art, and Art Institute of Chicago. Thayer

was also resourceful in his teaching, which he saw as a useful,

inseparable part of his own studio work. Among his devoted apprentices were Rockwell Kent, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, Richard Meryman, Barry Faulkner (Thayer's cousin), Alexander and William James (the sons of Harvard philosopher William James), and Thayer's own son and daughter, Gerald and Gladys. In a letter to Thomas Wilmer Dewing (c. 1917, in the collection of the Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution),

Thayer reveals that his method was to work on a new painting for only

three days. If he worked longer on it, he said, he would either

accomplish nothing or would ruin it. So on the fourth day, he would

instead take a break, getting as far from the work as possible, but

meanwhile instruct each student to make an exact copy of that three-day

painting. Then, when he did return to his studio, he would (in his

words) "pounce on a copy and give it a three-day shove again". As a result, he would end up with alternate versions of the same painting, in substantially different finished states. Thayer

is sometimes referred to as the “father of camouflage.” This is not

entirely unreasonable, because, while he did not invent camouflage, he

was undoubtedly one of the first to conduct extensive research on and

to write about certain aspects of protective coloration in nature. In

particular, beginning in 1892, he wrote about the function of countershading in

nature, by which forms appear less round and less solid through

inverted shading, by which he accounted for the white undersides of

animals. This finding is widely accepted today, and is sometimes now

called Thayer’s Law. He first became involved in military camouflage in 1898, during the Spanish - American War,

when he and his friend Brush proposed the use of protective coloration

on American ships, using countershading. While the war did not last

long enough for anything to come of this, the two artists did obtain a

patent for their idea in 1902, titled “Process of Treating the Outsides

of Ships, etc., for Making Them Less Visible” (U.S. Patent No. 715,013), in which their method is described as having been modeled on the coloration of a seagull. Thayer and Brush’s experiments in camouflage continued into World War I,

both collaboratively and separately. Early in that war, for example,

Brush developed a transparent airplane, while Thayer continued his

interest in disruptive or high-difference camouflage, which was not

unlike what British ship camouflage designer Norman Wilkinson would call dazzle camouflage (a

term that may have been inspired by Thayer's writings, which referred

to disruptive patterns in nature as “razzle dazzle”.) Gradually, Thayer

and Brush increasingly entrusted their camouflage work to the

responsibility of their sons. Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom (1909),

which had taken seven years to prepare, was credited to Thayer’s son,

Gerald. At about the same time, Thayer once again proposed ship

camouflage to the U.S. Navy (and was again unsuccessful), this time

working not with Brush, but with Brush's son, Gerome (named in honor of

his father's teacher). A few years later, with the start of World War I, Thayer ineptly made proposals to the British War Office, trying to persuade them to adopt a disruptively patterned field service uniform, in place of monochrome khaki. Meanwhile, Thayer and Gerome Brush’s

proposal for the use of countershading in ship camouflage was approved

for use on American ships, and a handful of Thayer enthusiasts (among

them Barry Faulkner and other Thayer students) recruited hundreds of

artists to join the American Camouflage Corps. By his own admission, Thayer often suffered from a condition that today is called bipolar disorder.

In his letters, he described it as “the Abbott pendulum,” by which his

emotions precariously swung back and forth between the two extremes of

(in his words) “all-wellity” and “sick disgust.” This condition

apparently worsened as the controversy grew about his camouflage

findings (most notably when they were denounced by former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt). As he aged, he increasingly suffered from panic attacks (which

he called “fright-fits”), nervous exhaustion, and suicidal thoughts, so

much so that he was no longer allowed to go out in his boat alone on Dublin Pond. At age 72, Thayer was disabled by a series of strokes, and died quietly at home on May 29, 1921.

In October 2008, the first and only documentary film about Thayer’s life and work premiered at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Titled Invisible: Abbott Thayer and the Art of Camouflage, it

featured a wide selection of his drawings and paintings, archival

photographs, historic documents, and interviews with humorist P.J. O'Rourke, Richard Meryman, Jr. (whose father was Thayer’s student), camouflage scholar Roy R. Behrens, Smithsonian curator Richard Murray, Thayer’s friends and relatives, and others.