<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Thomas Simpson, 1710

- Author Bolesław Prus, 1847

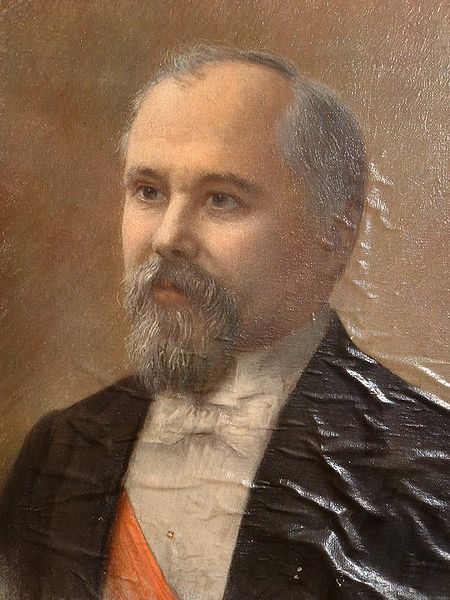

- Président de la République Française Raymond Poincaré, 1860

PAGE SPONSOR

Raymond Poincaré (20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of France on five separate occasions and as President of France from 1913 to 1920.

Born in Bar-le-Duc, Meuse, France, Raymond Poincaré was the son of Nicolas Antonin Hélène Poincaré, a distinguished civil servant and meteorologist. Raymond was also the cousin of Henri Poincaré, the famous mathematician. Educated at the University of Paris, Raymond was called to the Paris bar, and was for some time law editor of the Voltaire.

As a lawyer, he successfully defended Jules Verne in a libel suit presented against the famous author by the chemist Eugène Turpin, inventor of the explosive Melinite, who claimed that the "mad scientist" character in Verne's book "Facing the Flag" was based on himself. Poincaré had served for over a year in the Department of Agriculture when in 1887 he was elected deputy for the Meuse.

He made a great reputation in the Chamber as an economist, and sat on

the budget commissions of 1890 – 1891 and 1892. He was minister of

education, fine arts and religion in the first cabinet (April –

November 1893) of Charles Dupuy, and minister of finance in the second and third (May 1894 – January 1895). In Alexandre Ribot's

cabinet Poincaré became minister of public instruction. Although

he was excluded from the Radical cabinet which followed, the revised

scheme of death duties proposed by the new ministry was based upon his

proposals of the previous year. He became vice-president of the chamber

in the autumn of 1895, and in spite of the bitter hostility of the

Radicals retained his position in 1896 and 1897. Along with other followers of "Opportunist" Léon Gambetta, Poincaré founded the Democratic Republican Alliance (ARD) in 1902, which became the most important center-right party under the Third Republic. In 1906 he returned to the ministry of finance in the short-lived Sarrien ministry.

Poincaré had retained his practice at the bar during his

political career, and he published several volumes of essays on

literary and political subjects.

Poincaré became Prime Minister in

January 1912, and began pursuing a hard-line anti-German policy, noted

for restoring close ties with France's Russian ally. He went in Russia for a State visit in August 1912. He was elected President of the Republic in 1913, in succession to Armand Fallières and attempted to make that office into a site of power for the first time since MacMahon in the 1870s. He generally managed to continue to dominate foreign policy, in particular. He went in Russia, for the second time, but for the first time as a president, to reinforce the Franco-Russian Alliance, after Sarajevo, in July 1914. He became increasingly sidelined after the accession to power of Georges Clemenceau as Prime Minister in 1917. He believed the Armistice happened too soon and that the French Army should have penetrated Germany far more. At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, he wanted France to wrest the Rhineland from Germany to put it under Allied military control. Poincaré wrote a memorandum for the conference, saying that after the Franco - Prussian War Germany

occupied various French provinces and did not leave until they received

all of the indemnity, whereas France was asking for reparations for

damaged caused. He further claimed that if the Allies did not occupy

the Rhineland and at a later date found that they would need to do so

again, Germany would label them the aggressor: And,

further, shall we be sure of finding the left bank free from German

troops? Germany is supposedly going to undertake to have neither troops

nor fortresses on the left bank and within a zone extending 50 k.m.

east of the Rhine. But the Treaty does not provide for any permanent

supervision of troops and armaments on the left bank any more than

elsewhere in Germany. In the absence of this permanent supervision, the

clause stipulating that the League of Nations may order enquiries to be

undertaken is in danger of being purely illusory. We can thus have no

guarantee that after the expiry of the fifteen years and the evacuation

of the left bank, the Germans will not filter troops by degrees into

this district. Even supposing they have not previously done so, how can

we prevent them doing it at the moment when we intend to re-occupy on

account of their default? It will be simple for them to leap to the

Rhine in a night and to seize this natural military frontier well ahead

of us. The option to renew the occupation should not therefore from any

point of view be substituted for occupation. Ferdinand Foch urged

Poincaré to invoke his powers as laid down in the Constitution

and take over the negotiations of the treaty due to worries that

Clemenceau was not achieving France's aims. He

did not and when the French Cabinet approved of the terms Clemenceau

got Poincaré thought about resigning, although again he

refrained. In

1920, Poincaré's term as President came to an end, and two years

later he returned to office as Prime Minister. Once again, his tenure

was noted for its strong anti-German policies, with Poincaré

justifying these by saying: "Germany's population was increasing, her

industries were intact, she had no factories to reconstruct, she had no

flooded mines. Her resources were intact, above and below ground... In

fifteen or twenty years Germany would be mistress of Europe. In front

of her would be France with a population scarcely increased". Frustrated

at Germany's unwillingness to pay reparations, Poincaré hoped

for joint Anglo-French economic sanctions against Germany in 1922,

opposing military action. However by December 1922 he was faced with

British - American - German hostility and saw coal for French steel

production and money for reconstructing the devastated industrial areas

draining away. Poincaré was exasperated with British failure to

act, and wrote to the French ambassador in London: Judging

others by themselves, the English, who are blinded by their loyalty,

have always thought that the Germans did not abide by their pledges

inscribed in the Versailles Treaty because they had not frankly agreed

to them. ... We, on the contrary, believe that if Germany, far from

making the slightest effort to carry out the treaty of peace, has

always tried to escape her obligations, it is because until now she has

not been convinced of her defeat. ... We are also certain that Germany,

as a nation, resigns herself to keep her pledged word only under the

impact of necessity. Poincaré decided to occupy the Ruhr in

11 January 1923 to extract the reparations himself. This "was

profitable and caused neither the German hyperinflation, which began in

1922 and ballooned because of German responses to the Ruhr occupation,

nor the franc's 1924 collapse, which arose from French financial

practices and the evaporation of reparations". The profits, after Ruhr-Rhineland occupation costs, were nearly 900 million gold marks. Poincaré

lost the 1924 parliamentary election "more from the franc's collapse

and the ensuing taxation than from diplomatic isolation". Financial

crisis brought him back to power in 1926, and he once again became

Prime Minister and Finance Minister until his retirement in 1929. As early as in 1915, Raymond Poincaré introduced a controversial denaturalization law which was applied to naturalized French citizens with "enemy origins" who had continued to maintain their original nationality.

Through another law passed in 1927, the government could denaturalize

any new citizen who committed acts contrary to French "national

interest". He died in Paris in 1934.

His brother, Lucien Poincaré (b. 1862), famous as a physicist, became inspector-general of public instruction in 1902. He is the author of La Physique moderne (1906) and L'Électricité (1907). Jules Henri Poincaré (b. 1854), also a distinguished physicist and mathematician, belonged to another branch of the same family.