<Back to Index>

- Explorer Jean François de Galaup, Comte de Lapérouse, 1741

- Poet Edgar Lee Masters, 1868

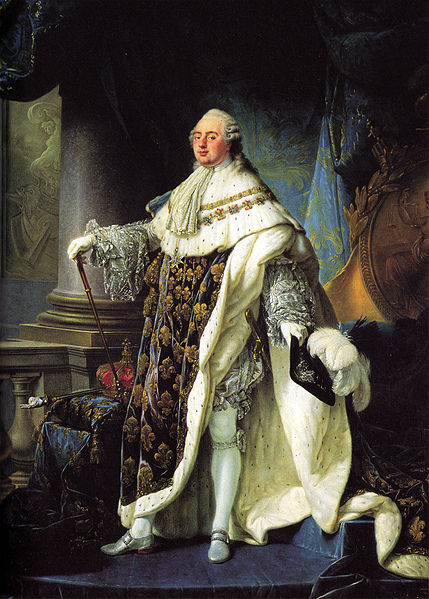

- King of France and of Navarre Louis XVI, 1754

PAGE SPONSOR

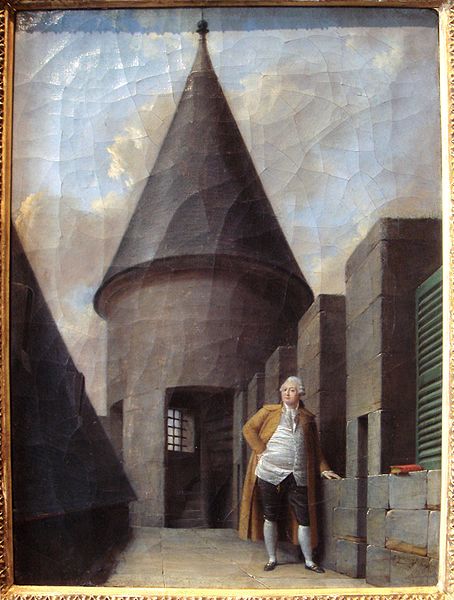

Louis XVI (23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) ruled as King of France and Navarre from 1774 until 1791, and then as King of the French from 1791 to 1792. Suspended and arrested during the Insurrection of 10 August 1792, he was tried by the National Convention, found guilty of high treason, and executed by guillotine on 21 January 1793. He was the only king of France ever to be executed.

Although

Louis XVI was beloved at first, his indecisiveness and conservatism led

some elements of the people of France to eventually view him as a

symbol of the perceived tyranny of the Ancien Régime. After the abolition of the monarchy in 1792, the new republican government gave him the surname Capet, a reference to the nickname of Hugh Capet, the founder of the Capetian dynasty - which the revolutionaries wrongly interpreted as a family name. Louis was also informally nicknamed Louis le Dernier (Louis the Last), a derisive use of the traditional nicknaming of French kings. Louis-Auguste de France, who was given the title Duc de Berry at birth, was born in the Palace of Versailles. Out of eight children, he was the third son of the Dauphin of France Louis-Ferdinand, and thus the grandson of Louis XV of France and of his consort, Maria Leszczyńska. His mother was Marie-Josèphe of Saxony, the daughter of Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, Prince-Elector of Saxony and King of Poland. Louis-Auguste

had a difficult childhood because his parents neglected him in favor of

his, said to be, bright and handsome older brother, Louis, duc de Bourgogne,

who died at the age of nine in 1761. A strong and healthy boy, but very

shy, Louis-Auguste excelled in his studies and had a strong taste for

Latin, history, geography and astronomy, and became fluent in Italian

and English. He enjoyed physical activities such as hunting with his

grandfather, Louis XV, and rough-playing with his younger brothers, Louis-Stanislas, comte de Provence, and Charles-Philippe, comte d'Artois.

From an early age, Louis-Auguste had been encouraged in another of his

hobbies: locksmithing, which was seen as a 'useful' pursuit for a child. Upon the death of his father, who died of tuberculosis on 20 December 1765, the eleven year old Louis-Auguste became the new Dauphin. His mother, who had never recovered from the loss of her husband, died on 13 March 1767, also from tuberculosis. The strict and conservative education he received from the Duc de La Vauguyon,

"gouverneur des Enfants de France" (governor of the Children of

France), from 1760 until his marriage in 1770, did not prepare him for

the throne that he was to inherit in 1774 after the death of his grandfather. On 16 May 1770, at the age of fifteen, Louis-Auguste married the fourteen year old Habsburg Archduchess Maria Antonia (better known by the French form of her name, Marie Antoinette), his second cousin once removed and the youngest daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Francis I and his wife, the formidable Empress Maria Theresa. This

marriage was met with some hostility by the French public. France's alliance with Austria had pulled France into the disastrous Seven Years War,

in which France was defeated by the British, both in Europe and in

North America. By the time that Louis-Auguste and Marie-Antoinette were

married, the people of France generally regarded the Austrian alliance

with dislike, and Marie-Antoinette was seen as an unwelcome foreigner. For

the young couple, the marriage was initially amiable but distant —

Louis-Auguste's shyness meant that he failed to consummate the union,

much to his wife's distress, while his fear of being manipulated by her

for Imperial purposes caused him to behave coldly towards her in public. Over time, the couple became closer, and their marriage was reportedly consummated in July 1773.

Nevertheless, the royal couple failed to parent any children for

several years after this, placing a strain upon their marriage, whilst the situation was worsened by the publication of obscene pamphlets (libelles) which mocked the infertility of the pair. One questioned, "Can the King do it? Can't the King do it?" The

reasons behind the couple's initial failure to have children were

debated at that time, and they have continued to be so since. One

suggestion is that Louis-Auguste suffered from a sexual dysfunction, perhaps phimosis, a suggestion first made in late 1772 by the royal doctors. Historians adhering to this view suggest that he was circumcised (the

common cure for phimosis) to relieve the condition seven years after

their marriage. Louis's doctors were not in favor of the surgery — the

operation was delicate and traumatic, and capable of doing "as much

harm as good" to an adult male. As late as 1777, the Prussian envoy,

Baron Goltz, reported that the King of France had definitely declined the operation. In the long run, and in spite of all their earlier difficulty, the Royal couple became the parents of four children: When

Louis XVI succeeded to the throne in 1774, he was not yet 20 years old.

He had an enormous responsibility, as the government was deeply in

debt, and resentment towards 'despotic' monarchy was on the rise. Louis

also felt woefully unqualified for the job. He aimed to earn the love

of his people by reinstating the parlements. While none doubted Louis's intellectual ability to rule France, it was quite clear that, although raised as the Dauphin since

1765, he lacked firmness and decisiveness. In spite of his

indecisiveness, Louis was determined to be a good king, stating that he

"must always consult public opinion; it is never wrong." Louis therefore appointed an experienced advisor, Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, comte de Maurepas, who, until his death in 1781, would take charge of many important ministerial functions. Radical financial reforms by Turgot and Malesherbes angered the nobles and were blocked by the parlements who

insisted that the King did not have the legal right to levy new taxes.

So, in 1776, Turgot was dismissed and Malesherbes resigned, to be

replaced by Jacques Necker. Necker supported the American Revolution,

and he carried out a policy of taking out large international loans

instead of raising taxes. When this policy failed miserably, Louis

dismissed him, and then replaced him in 1783 with Charles Alexandre de Calonne, who increased public spending to "buy" the country's way out of debt. Again this failed, so Louis convoked the Assembly of Notables in

1787 to discuss a revolutionary new fiscal reform proposed by Calonne.

When the nobles were informed of the extent of the debt, they were

shocked into rejecting the plan. This negative turn of events signaled

to Louis that he had lost the ability to rule as an absolute monarch,

and he fell into depression. As power drifted from him, there were increasingly loud calls for him to convoke the Estates-General, which had not met since 1614, at the beginning of the reign of Louis XIII.

As a last-ditch attempt to get new monetary reforms approved, Louis XVI

convoked the Estates-General on 8 August 1788, setting the date of

their opening at 1 May 1789. With the convocation of the

Estates-General, as in many other instances during his reign, Louis

placed his reputation and public image in the hands of those who were

perhaps not as sensitive to the desires of the French public as he was.

Because it had been so long since the Estates-General had been

convened, there was some debate as to which procedures should be

followed. Ultimately, the parlement de Paris agreed

that "all traditional observances should be carefully maintained to

avoid the impression that the Estates-General could make things up as

it went along." Under this decision, the King agreed to retain many of

the divisionary customs which had been the norm in 1614, but which were

intolerable to a Third Estate buoyed by the recent proclamations of

equality. For example, the First and Second Estates proceeded into the

assembly wearing their finest garments, while the Third Estate was

required to wear plain, oppressively somber black, an act of alienation

that Louis would likely have not condoned. He seemed to regard the

deputies of the Estates-General with at least respect: in a wave of

self-important patriotism, members of the Estates refused to remove

their hats in the King's presence, so Louis removed his to them. This convocation was one of the events that transformed the general economic and political malaise of the country into the French Revolution, which began in June 1789, when the Third Estate unilaterally declared itself the National Assembly. Louis's attempts to control it resulted in the Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), on 20 June, and the declaration of the National Constituent Assembly on

9 July. Within three short months, the majority of the king's executive

authority had been transferred to the elected representatives of the

people's nation. The storming of the Bastille on 14 July served to reinforce and emphasize this radical change in the mind of the masses. French involvement in the Seven Years War had left Louis XVI a disastrous inheritance.Britain's victories had seen them capture most of France's colonial territories. While some were returned to France at the 1763 Treaty of Paris a vast swathe of North America was ceded to the British. This

had led to a strategy amongst the French leadership of seeking to

rebuild the French military in order to fight a war of revenge against

Britain, in which it was hoped the lost colonies could be recovered.

France still maintained a strong influence in the West Indies, and in

India maintained five trading posts, leaving opportunities for disputes

and power-play with Great Britain. In

the spring of 1776, Vergennes, the Foreign Secretary, saw an

opportunity to humiliate France's long-standing enemy, Great Britain,

by supporting the American Revolution. Louis XVI was convinced by Benjamin Franklin to send financial aid and large quantities of munitions, sign a formal Treaty of Alliance in 1778, and go to war with Britain. Spain and the Netherlands joined the French. France sent Rochambeau, Lafayette and de Grasse,

to help the Americans, along with large land and naval forces. French

aid proved decisive in forcing the main British army to surrender at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. The Americans gained their independence, and the war ministry rebuilt the French Army. However, the British defeated the main French fleet in 1782 and France gained little from the Treaty of Paris (of 1783) that ended the war, but the war cost 1,066 million livres,

financed by new loans at high interest (with no new taxes). Necker

concealed the crisis from the public by explaining only that ordinary

revenues exceeded ordinary expenses, and not mentioning the loans.

After he was forced from office in 1781, new taxes were levied.

Louis XVI also wished to expel the British from India. In 1782, Louis XVI sealed an alliance with the Peshwa Madhu Rao Narayan. As a consequence Bussy moved his troops to the Île de France (Mauritius) and later contributed to the French effort in India in 1783. Suffren became the ally of Hyder Ali in the Second Anglo-Mysore War against British rule in India, in 1782 - 1783, fighting the British fleet along the coasts of India and Ceylon. France also intervened in Vietnam following Mgr Pigneau de Behaine's intervention to obtain military aid. A France - Vietnam alliance was signed through the Treaty of Versailles of 1787, between Louis XVI and Prince Nguyễn Ánh.

As the French regime was under considerable strain, France was unable

to follow through with the application of the Treaty, but Mgr Pigneau

de Behaine persisted in his efforts and with the support of French

individuals and traders mounted a force of French soldiers and officers

that would contribute to the modernization of the armies of Nguyễn

Ánh, contributing to his victory and his reconquest of all of

Vietnam by 1802. Louis XVI also encouraged major voyages of exploration. In 1785, he appointed La Pérouse to lead a sailing expedition around the world.

On 5 October 1789, an angry mob of Parisian working women was incited by revolutionaries and marched on the Palace of Versailles,

where the royal family lived. During the night, they infiltrated the

palace and attempted to kill the queen, who was associated with a

frivolous lifestyle that symbolized much that was despised about the Ancien Régime. After the situation had been defused, the king and his family were brought by the crowd to the Tuileries Palace in

Paris. The reasoning behind this forced departure from Versailles was

the opinion the king would be more accountable to the people if he

lived among them in Paris. Initially,

after the removal of the royal family to Paris, Louis maintained a

certain level of popularity by acquiescing to many of the social,

political, and economic reforms of the revolutionaries. Unbeknownst to

the public, however, recent scholarship has concluded that Louis began to suffer at the time from severe bouts of clinical depression, which left him prone to paralyzing indecisiveness.

During these indecisive moments, his wife, the unpopular queen, was

essentially forced into assuming the role of decision-maker for the

Crown.

The

revolution's principles of popular sovereignty, though central to

democratic principles of later eras, marked a decisive break from the

absolute monarchical principle that was at the heart of traditional

French government. As a result, the revolution was opposed by many of

the rural people of France and by practically all the governments of

France's neighbors. As the revolution became more radical and the

masses became more uncontrollable, several leading figures in the

initial formation of the revolution began to doubt its benefits. Some

like Honoré Mirabeau secretly plotted with the Crown to restore its power in a new constitutional form. Beginning in 1791, Montmorin,

Minister of Foreign Affairs, started to organize covert resistance to

the Revolutionary forces. Thus, the funds of the Civil List (la Liste civile), voted annually by the National Assembly were partially assigned to secret expenses in order to preserve the monarchy. Arnault Laporte was in charge of the Civil List and he collaborated with both Montmorin and Mirabeau. After the sudden death of Mirabeau, Maximilien Radix de Sainte-Foix,

a noted financier, took his place. In effect, he headed a secret

council of advisers to the King that tried to preserve the Monarchy;

these schemes proved unsuccessful, and were exposed later as the armoire de fer scandal. Mirabeau's

death, and Louis's indecision, fatally weakened negotiations between

the Crown and moderate politicians. On one hand, Louis was nowhere near

as reactionary as his brothers, the comte de Provence and the comte d'Artois,

and he repeatedly sent messages to them requesting a halt to their

attempts to launch counter-coups. This was often done through his

secretly nominated regent, the Cardinal Loménie de Brienne.

On the other hand, Louis was alienated from the new democratic

government both by its negative reaction to the traditional role of the

monarch and in its treatment of him and his family. He was particularly

irked by being kept essentially as a prisoner in the Tuileries, where

his wife was being humiliatingly forced to have revolutionary soldiers

in her private bedroom watching her as she slept, and by the refusal of

the new regime to allow him to have confessors and priests of his

choice rather than 'constitutional priests' pledged to the state and

not the Roman Catholic Church. On 21 June 1791, Louis attempted to secretly flee with his family from Paris to the royalist fortress town of Montmédy on the northeastern border of France. While

the National Assembly worked painstakingly towards a constitution,

Louis and Marie-Antoinette were involved in plans of their own. Louis

had appointed the baron de Breteuil to act as plenipotentiary, dealing

with other foreign heads of state in an attempt to bring about a

counter-revolution. As tensions in Paris rose and Louis was pressured

to accept measures from the Assembly against his will, the King and

Queen plotted to secretly escape from France. Beyond escape, they hoped

to raise an "armed congress" with the help of the émigrés who

had fled, as well as assistance from other nations, with which they

could return and, in essence, recapture France. This degree of planning

reveals Louis’ determination to do what he thought was right for his

country beneath his superficial appearance of apathy, although

unfortunately it was for this determined plot that he was eventually

convicted of high treason. However, flaws in its plan and lack of rapidity were responsible for the failure of the escape. The royal family was arrested at Varennes-en-Argonne shortly after Jean-Baptiste Drouet, postmaster of the town of Sainte-Menehould, had recognised the king from his profile on a golden écu,

and had given the alert. Louis XVI and his family were brought back to

Paris where they arrived on 25 June. Viewed suspiciously as traitors,

they were placed under tight house arrest upon their return to the Tuileries. The other monarchies of

Europe looked with concern upon the developments in France, and

considered whether they should intervene, either in support of Louis or

to take advantage of the chaos in France. The key figure was Marie

Antoinette's brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II.

Initially, he had looked on the revolution with equanimity. However, he

became more and more disturbed as it became more and more radical.

Despite this, he still hoped to avoid war. On 27 August, Leopold and King Frederick William II of Prussia, in consultation with émigrés French nobles, issued the Declaration of Pillnitz,

which declared the interest of the monarchs of Europe in the well-being

of Louis and his family, and threatened vague but severe consequences

if anything should befall them. Although Leopold saw the Pillnitz

Declaration as an easy way to appear concerned about the developments

in France without committing any soldiers or finances to change them,

the revolutionary leaders in Paris viewed it fearfully as a dangerous

foreign attempt to undermine France's sovereignty. In

addition to the ideological differences between France and the

monarchical powers of Europe, there were continuing disputes over the

status of Austrian estates in Alsace, and the concern of members of the National Constituent Assembly about the agitation of émigrés nobles abroad, especially in the Austrian Netherlands and the minor states of Germany. In the end, the Legislative Assembly,

supported by Louis, declared war on the Holy Roman Empire first, voting

for war on 20 April 1792, after a long list of grievances was presented

to it by the foreign minister, Charles François Dumouriez.

Dumouriez prepared an immediate invasion of the Austrian Netherlands,

where he expected the local population to rise against Austrian rule.

However, the revolution had thoroughly disorganised the army, and the

forces raised were insufficient for the invasion. The soldiers fled at

the first sign of battle, deserting en masse and, in one case, murdering their general. While

the revolutionary government frantically raised fresh troops and

reorganised its armies, a mostly Prussian allied army under Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick assembled at Coblenz on the Rhine. In July, the invasion commenced, with Brunswick's army easily taking the fortresses of Longwy and Verdun. The duke then issued on 25 July a proclamation called the Brunswick Manifesto, written by Louis's émigré cousin, the Prince de Condé,

declaring the intent of the Austrians and Prussians to restore the king

to his full powers and to treat any person or town who opposed them as

rebels to be condemned to death by martial law. Contrary

to its intended purpose of strengthening the position of the King

against the revolutionaries, the Brunswick Manifesto had the opposite

effect of greatly undermining Louis's already highly tenuous position

in Paris. It was taken by many to be the final proof of a collusion

between Louis and foreign powers in a conspiracy against his own

country. The anger of the populace boiled over on 10 August when a

group of Parisians — with the backing of a new municipal government of

Paris that came to be known as the "insurrectionary" Paris Commune — besieged the Tuileries Palace. The king and the royal family took shelter with the Legislative Assembly. Louis was officially arrested on the 13th of August, 1792, and sent to the Temple, an ancient fortress in Paris that was used as a prison. On 21 September, the National Assembly declared France to be a Republic and abolished the Monarchy. The Girondins were

partial to keeping the deposed king under arrest, both as a hostage and

a guarantee for the future. The more radical members – mainly the

Commune and the Parisian deputies who would soon be known as the Mountain –

argued for Louis's immediate execution. The legal background of many of

the deputies made it difficult for a great number of them to accept an

execution without the due process of law of

some sort, and it was voted that the deposed monarch be tried before

the National Convention, the organ that housed the representatives of

the sovereign people. In November 1792, Armoire de fer (French: 'iron chest') incident took place at the Tuileries Palace.

This was believed to have been a hiding place at the Royal apartments,

where some secret documents were kept. The existence of this iron

cabinet was publicly revealed to Jean-Marie Roland, Girondinist Minister of the Interior. The resulting scandal served to discredit the King. On

11 December, among crowded and silent streets, the deposed King was

brought from the Temple to stand before the Convention and hear his indictment, an accusation of high treason and crimes against the State. On 26 December, his counsel, Raymond de Sèze, delivered Louis's response to the charges, with the assistance of François Tronchet and Malesherbes.

On

15 January 1793, the Convention, composed of 721 deputies, voted on the

verdict. Given overwhelming evidence of Louis's collusion with the

invaders, the verdict was a foregone conclusion — with 693 deputies

voting guilty, none for acquittal, with 23 abstaining. The next day, a

roll-call vote was carried out to decide upon the fate of the King, and

the result was uncomfortably close for such a dramatic decision. 288 of

the Deputies voted against death and for some other alternative, mainly

some means of imprisonment or exile. 72 of the Deputies voted for the

death penalty, but subject to a number of delaying conditions and

reservations. 361 of the Deputies voted for Louis's immediate death.

The

next day, a motion to grant Louis XVI reprieve from the death sentence

was voted down: 310 of the Deputies requested mercy, but 380 of the

Deputies voted for the immediate execution of the death penalty. This

decision would be final. On Monday, 21 January 1793, stripped of all

titles and honorifics by the Republican Government, Citoyen Louis Capet was beheaded by guillotine in front of a cheering crowd in what today is the Place de la Concorde. The executioner, Charles Henri Sanson, testified that the former King had bravely met his fate. As

Louis mounted the scaffold he appeared dignified and resigned. He

delivered a short speech in which he reasserted his innocence and he

pardoned those responsible for his death. He declared himself willing

to die and prayed that the people of France would be spared a similar

fate. He seemed about to say more when Antoine-Joseph Santerre, a general in the National Guard, cut Louis off by ordering a drum roll. The former King was then quickly beheaded. Some

accounts of Louis's beheading indicate that the blade did not sever his

neck entirely the first time. There are also accounts of a

blood-curdling scream issuing from Louis after the blade fell but this

is unlikely, since the blade severed Louis's spine. It is agreed that

while Louis's blood dripped to the ground many members of the crowd ran

forward to dip their handkerchiefs in it. The regicide has loomed as a shadow over French history. The 19th-century historian, Jules Michelet, attributed the restoration of the French monarchy to the sympathy that had been engendered by the execution. Michelet's Histoire de la Révolution Française and Alphonse de Lamartine's Histoire des Girondins,

in particular, showed the marks of the feelings aroused by the

revolution's regicide. The two writers did not share the same

sociopolitical vision, but they agreed that, even though the monarchy

was rightly ended in 1792, the lives of the royal family should have

been spared. Lack of compassion at that moment contributed to a

radicalization of revolutionary violence and to greater divisiveness

among Frenchmen. Because Louis XVI was a merciful man, the

revolutionaries' passions needed to be balanced by compassion and by

less fanatical sentiments. For the 20th century novelist Albert Camus the execution signaled the end of the role of God in history, for which he mourned. For the 20th century philosopher Jean-François Lyotard the

regicide was the starting point of all French thought, the memory of

which acts as a reminder that French modernity began under the sign of

a crime. The

Duchess of Angoulême, the daughter of Louis XVI, survived the

French Revolution, and she lobbied in Rome energetically for the

canonization of her father as a saint of the Catholic Church. Despite

his signing of the "Civil Constitution of the Clergy", Louis had been

described as a martyr by Pope Pius VI in 1793. In 1820, however, a

memorandum of the Congregation of Rites in Rome, declaring the

impossibility of proving that Louis had been executed for religious

rather than political reasons, put an end to hopes of canonization.