<Back to Index>

- Historian Heinrich Karl Ludolf von Sybel, 1817

- Opera Singer Maria Callas, 1923

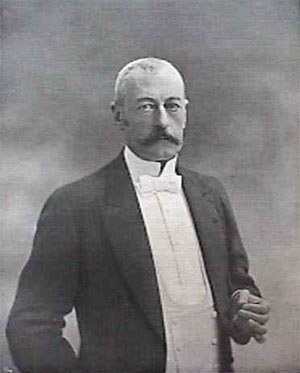

- Prime Minister of France Pierre Marie René Ernest Waldeck-Rousseau, 1846

PAGE SPONSOR

Pierre Marie René Ernest Waldeck-Rousseau (2 December 1846 - 10 August 1904) was a French Republican statesman.

Pierre

Waldeck-Rousseau was born in Nantes, Loire-Atlantique.

His father, René

Waldeck-Rousseau, a barrister at the Nantes bar and a

leader of the local republican party,

figured in the revolution of 1848 as one of the deputies returned to the Constituent

Assembly for Loire

Inférieure. The

son was a delicate child whose eyesight made reading difficult, and his

early education was therefore entirely oral. He studied law at Poitiers

and in Paris, where he took his licentiate in January 1869. His

father's record ensured his reception in high republican circles. Jules

Grévy stood

sponsor for him at the Parisian bar.

After six months of waiting for briefs in Paris, he decided to return

home and joined the bar of St Nazaire early in 1870. In September

he became, in spite of his youth, secretary to the municipal commission temporarily

appointed to carry on the town business. He organized the National Defence at

St Nazaire, and himself marched out with his contingent, though they

saw no active service owing to lack of ammunition, their private store

having been commandeered by the state. In 1873,

following the establishment of the Third Republic in 1871, he moved to the

bar of Rennes,

and six years later was returned to the Chamber of

Deputies.

In his electoral program he had stated that he was prepared to respect

all liberties except those of conspiracy against the institutions of

the country and of educating the young in hatred of the modern social

order. In the Chamber he supported the policy of Léon

Gambetta. The Waldeck-Rousseau family was strictly Catholic in spite of its republican

principles; nevertheless Waldeck-Rousseau supported the Jules Ferry

laws on public, laic and mandatory education, enacted in 1881 -

1882. In 1881 he became minister of the

interior in

Gambetta's grand ministry. He further voted for the abrogation of the

law of 1814 forbidding work on Sundays and fast days, for compulsory

service of one year for seminarists and for the re-establishment of divorce.

He made his reputation in the Chamber by a report which he drew up in

1880 on behalf of the committee appointed to inquire into the French judicial

system. He was

chiefly occupied with the relations between capital and labour, and had

a large share in securing the recognition of

trade unions in

1884. He became again minister of the interior in the Jules Ferry cabinet

of 1883 - 1885, when he gave proof of great administrative powers. He

sought to put down the system by which civil posts were obtained

through the local deputy, and he made it clear that the central

authority could not be defied by local officials. Waldeck-Rousseau also

deposed the 27 May 1885 act establishing penal colonies,

dubbed "Law on relegation of recidivists",

along with Martin

Feuillée. The law was supported by Gambetta and his

friend, the criminologist Alexandre

Lacassagne. Waldeck-Rousseau

had

begun to practise at the Paris bar in 1886, and in 1889 he did not

seek re-election to the Chamber, but devoted himself to his legal work.

The most famous of the many noteworthy cases in which his cold and

penetrating intellect and his power of clear exposition were retained

was the defense of Gustave Eiffel in the Panama scandals of 1893. In 1894

he returned to political life as senator for the department of the Loire,

and next year stood for the presidency of the republic against Félix

Faure and Henri Brisson,

being

supported by the Conservatives, who were soon to be his bitter

enemies. He received 184 votes, but retired before the second ballot to

allow Faure to receive an absolute majority. During the political

crisis of the next few years he was recognized by the Opportunist

Republicans as

the successor of Jules Ferry and Gambetta, and at the crisis of 1899 on

the fall of the Charles Dupuy cabinet he was asked by

President Émile

Loubet to form a

government. After an

initial failure he succeeded in forming a coalition cabinet of

"Republican Defense", supported by the Radical -

Socialists and the Socialists,

which included such widely different politicians as the Socialist Alexandre

Millerand and the General de

Galliffet, dubbed the "repressor of the Commune".

He

himself returned to his former post at the ministry of the interior,

and set to work to quell the discontent with which the country was

seething, to put an end to the various agitations which under specious

pretences were directed against republican institutions (far-right

leagues, Boulangist

crisis,

etc.), and to restore independence to the judicial authority. His

appeal to all republicans to sink their differences before the common

peril met with some degree of success, and enabled the government to

leave the second court-martial of Alfred Dreyfus at

Rennes an absolutely free hand, and then to compromise the affair by

granting a pardon to Dreyfus. Waldeck-Rousseau won a great personal

success in October by his successful intervention in the strikes at Le

Creusot. With the

condemnation in January 1900 of Paul

Deroulède and

his

nationalist followers by the High Court the worst of the danger was

past, and Waldeck-Rousseau kept order in Paris without having recourse

to irritating displays of force. The Senate was staunch in support of

Waldeck-Rousseau, and in the Chamber he displayed remarkable astuteness

in winning support from various groups. The Amnesty Bill, passed on 19

December, chiefly through his unwearied advocacy, went far to smooth

down the acerbity of the preceding years. With the object of aiding the

industry of wine producing, and of discouraging the consumption of

spirits and other deleterious liquors, the government passed a bill

suppressing the octroi duties on the three

"hygienic" drinks -- wine, cider and beer. The act came into force at

the beginning of 1901. But

the most important measure of his later administration was the

Associations Bill of 1901. Like many of his predecessors, he was

convinced that the stability of the republic demanded some restraint on

the intrigues of the wealthy religious bodies. All previous attempts in

this direction had failed. In his speech in the Chamber,

Waldeck-Rousseau recalled the fact that he had tried to pass an

Associations Bill in 1882, and again in 1883. He declared that the

religious associations were now being subjected for the first time to

the regulations common to all others, and that the object of the bill

was to ensure the supremacy of the civil power. The royalist bias given

to the pupils in the religious seminaries was undoubtedly a principal

cause of the passing of this bill; and the government took strong

measures to secure the presence of officers of undoubted fidelity to

the republic in the higher positions on the staff. His speeches on the

religious question were published in 1901 under the title of Associations et

congregations, following a volume of speeches on Questions societies (1900). As the general

election of 1902 approached

all sections of the Opposition united their efforts under the Bloc des gauches,

and

the name of Waldeck-Rousseau served as a battle-cry for one side,

and on the other as a target for abuse. The result was a decisive

victory for republican stability. With the defeat of the machinations

against the republic, Waldeck-Rousseau considered his task ended, and

on 3 June 1902 he resigned office, having proved himself the "strongest

personality in French politics since the death of Gambetta." He emerged from his retirement

to protest in the Senate against the construction put on his

Associations Bill by Émile

Combes, who refused in mass the applications of the teaching and

preaching congregations for official recognition. His

speeches were published as Discours

parlementaires (1889); Pour la

République, 1883 - 1903 (1904),

edited by H Leyret; L'État et la

liberté (1906);

and his Plaidoyers (1906) were edited by H

Barboux. See also H Leyret, Waldeck-Rousseau

et la Troisième République (1908).