<Back to Index>

- Inventor Samuel Crompton, 1753

- Composer Nino Rota, 1911

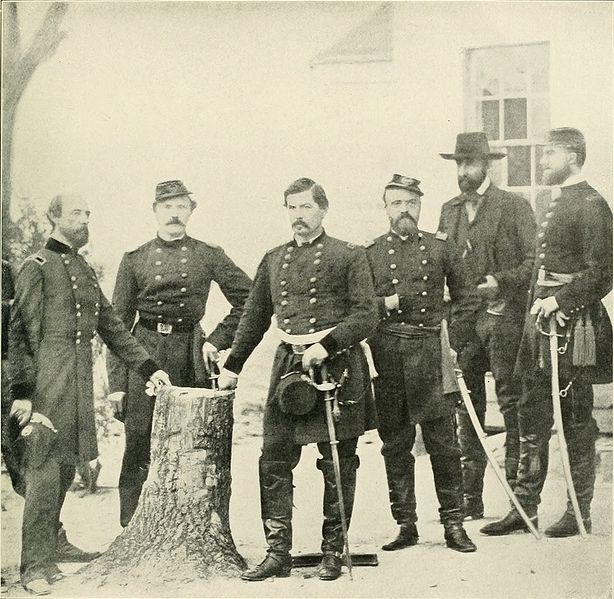

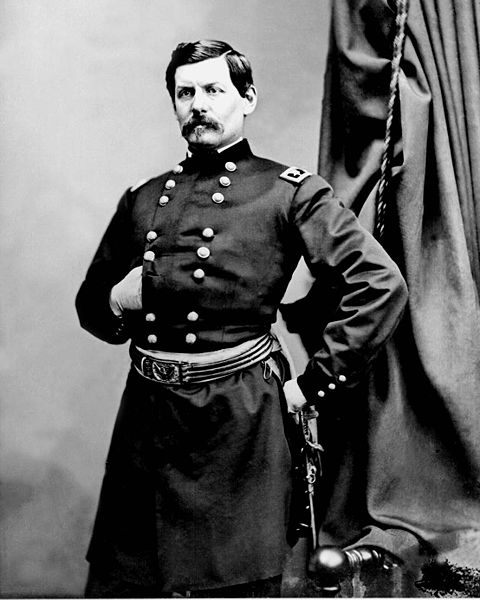

- Major General of the Union Army George Brinton McClellan, 1826

PAGE SPONSOR

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly (November 1861 to March 1862) as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well trained and organized army for the Union. Although McClellan was meticulous in his planning and preparations, these characteristics may have hampered his ability to challenge aggressive opponents in a fast moving battlefield environment. He chronically overestimated the strength of enemy units and was reluctant to apply principles of mass, frequently leaving large portions of his army unengaged at decisive points.

McClellan's Peninsula

Campaign in 1862

ended in failure, with retreats from attacks by General Robert E. Lee's

smaller Army of Virginia and an unfulfilled plan to

seize the Confederate capital of Richmond.

His performance at the bloody Battle of

Antietam blunted

Lee's invasion of Maryland, but allowed Lee to eke out a precarious

tactical draw and avoid destruction, despite being outnumbered. As a

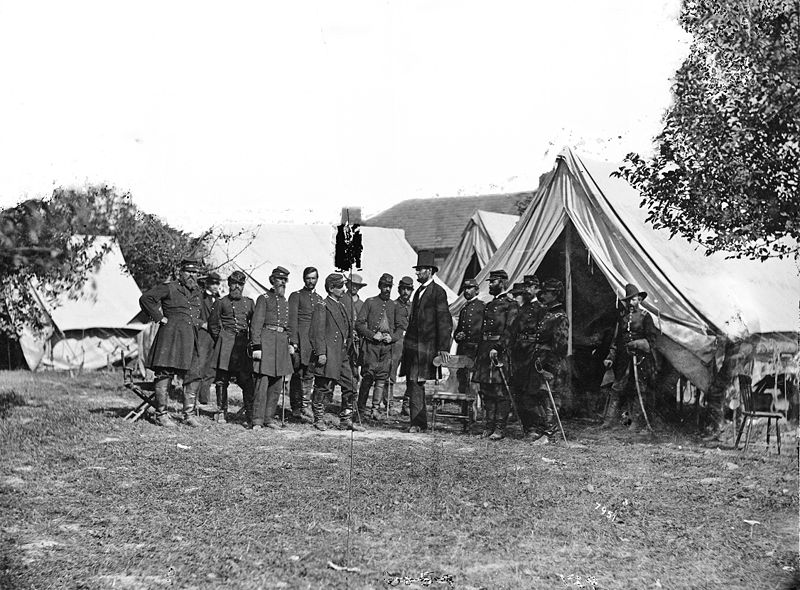

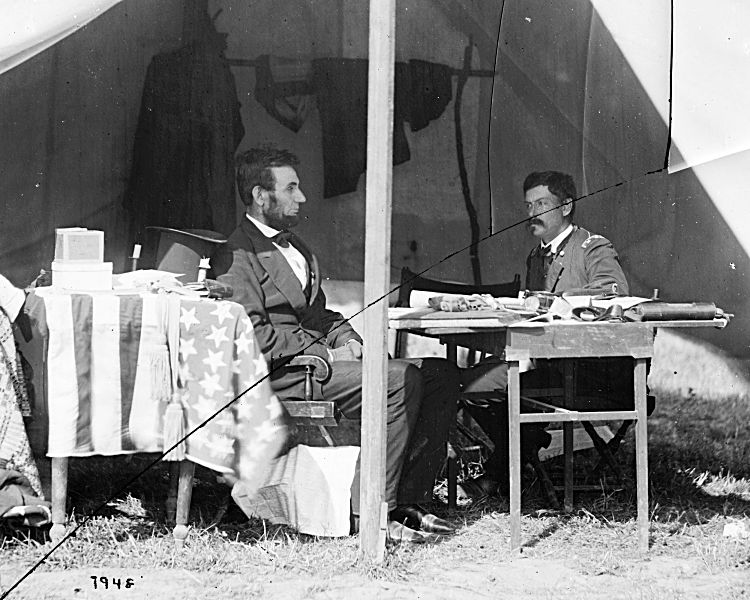

result, McClellan's leadership skills during battles were questioned by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln,

who

eventually removed him from command, first as general-in-chief,

then from the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln offered this famous

evaluation of McClellan: "If he can't fight himself, he excels in

making others ready to fight." Indeed,

McClellan

was the most popular of that army's commanders with its

soldiers, who felt that he had their morale and well-being as paramount

concerns. General

McClellan also failed to maintain the trust of Lincoln, and proved to

be frustratingly derisive of, and insubordinate to, his commander-in-chief.

After he was relieved of command, McClellan became the unsuccessful Democratic nominee opposing Lincoln in

the 1864

presidential election.

His party had an anti-war platform, promising to end the war and

negotiate with the Confederacy, which McClellan was forced to

repudiate, damaging the effectiveness of his campaign. He served as the 24th Governor of New Jersey from 1878 to 1881. He

eventually became a writer, defending his actions during the Peninsula

Campaign and the Civil War. Although

the majority of modern authorities assess McClellan as a poor

battlefield general, a small but vocal faction of historians maintain

that he was a highly capable commander, but his reputation suffered

unfairly at the hands of pro-Lincoln partisans who needed a scapegoat

for the Union's setbacks. His legacy therefore defies easy

categorization. After the war,

Ulysses S. Grant was asked to evaluate McClellan as a

general. He replied, "McClellan is to me one of the mysteries of the

war." McClellan

was born in Philadelphia,

the son of a prominent surgical ophthalmologist,

Dr. George McClellan, the founder of Jefferson

Medical College.

His mother was Elizabeth Steinmetz Brinton McClellan, daughter of a

leading Pennsylvania family, a woman noted for her "considerable grace

and refinement". The

couple produced five children: a daughter, Frederica; then three sons,

John, George, and Arthur; and a second daughter, Mary. McClellan was

the grandson of Revolutionary

War general Samuel McClellan of Woodstock,

Connecticut. He first attended the University of

Pennsylvania in

1840 at age 13, resigning himself to the study of law. After two years,

he changed his goal to military service. With the assistance of his

father's letter to President John Tyler,

young George was accepted at the United States

Military Academy in

1842, the academy having waived its normal minimum age of 16. At West

Point, he was an energetic

and ambitious cadet, deeply interested in the teachings of Dennis

Hart Mahan and the theoretical strategic principles

of Antoine-Henri

Jomini. His closest friends

were aristocratic Southerners such as James Stuart, Dabney

Maury, Cadmus

Wilcox, and A.P.

Hill.

These associations gave McClellan what he considered to be an

appreciation of the Southern mind, an understanding of the political

and military implications of the sectional differences in the United

States that led to the Civil War. He graduated in 1846, second in his class

of 59 cadets, losing the top position (to Charles

Seaforth Stewart) only

because of poor drawing skills. He was commissioned a brevet second

lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps

of Engineers. McClellan's

first

assignment was with a company of engineers formed at West Point,

but he quickly received orders to sail for the Mexican -

American War. He arrived near the mouth of the Rio Grande in October 1846, well

prepared for action with a double barreled shotgun, two pistols, a

saber, a dress sword, and a Bowie knife.

He complained that he had arrived too late to take any part in the

American victory at Monterrey in September. During a

temporary armistice in which the forces of Gen. Zachary Taylor awaited action, McClellan

was stricken with dysentery and malaria,

which kept him in the hospital for nearly a month. The malaria would

recur in later years — he called it his "Mexican disease." He served bravely as an

engineering officer during the war, subjected to frequent enemy fire,

and was appointed a brevet first lieutenant for Contreras and Churubusco and to captain for Chapultepec. He performed reconnaissance

missions for Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott,

a close friend of McClellan's father. McClellan's

experiences during the war developed various attitudes that affected

his later military and political life. He learned to appreciate the

value of flanking movements over frontal assaults (used by Scott at Cerro

Gordo) and the value of siege

operations (Vera

Cruz).

He witnessed Scott's success in balancing political with military

affairs, and his good relations with the civil population as he

invaded, enforcing strict discipline on his soldiers to minimize damage

to their property. And he developed a disdain for volunteer soldiers

and officers, particularly politicians who cared nothing for discipline

and training. McClellan

returned

to West Point to command his engineering company, which was

attached to the academy for the purpose of training cadets in

engineering activities. He chafed at the boredom of peacetime garrison

service, although he greatly enjoyed the social life. In June 1851 he

was ordered to Fort Delaware,

a masonry work under construction on an island in the Delaware River,

40 miles (64 km) downriver from Philadelphia. In March 1852 he was

ordered to report to Capt. Randolph B.

Marcy at Fort Smith, Arkansas,

to serve as second in command on an expedition to discover the sources

of the Red River.

By

June the expedition reached the source of the north fork of the

river and Marcy named a small tributary McClellan's Creek. Upon their

return to civilization on July 28, they were astonished to find that

they had been given up for dead. A sensational story had reached the

press, which McClellan blamed on "a set of scoundrels, who seek to keep

up agitation on the frontier in order to get employment from the Govt.

in one way or other," that the expedition had been ambushed by 2,000 Comanches and killed to the last man. In

the

fall of 1852, McClellan published a manual on bayonet tactics that

he had translated from the original French. He also received an

assignment to the Department of Texas, with orders to perform a survey

of Texas rivers and harbors. In 1853 he participated in the Pacific

Railroad surveys, ordered by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis,

to select an appropriate route for the upcoming transcontinental

railroad. McClellan surveyed the northern corridor along the

47th and 49th parallels from St. Paul to the Puget Sound.

During this assignment, he demonstrated a tendency for insubordination

toward senior political figures. Isaac Stevens,

governor of the Washington

Territory, became dissatisfied with McClellan's performance in

scouting passes across the Cascade Range.

(McClellan selected Yakima Pass without a thorough reconnaissance and

refused the governor's order to lead a party through it in winter

conditions, relying on faulty intelligence about the depth of snowpack

in that area. He also neglected to find three greatly superior passes

in the near vicinity, which would be the ones eventually used for

railroads and interstate highways.) The governor ordered McClellan to

turn over his expedition logbooks, but McClellan steadfastly refused,

most likely because of embarrassing personal comments that he had made

throughout. Returning

to

the East, McClellan began courting Ellen Mary Marcy (1836 – 1915), the

daughter of his former commander. Ellen, or Nelly, refused McClellan's

first proposal of marriage, one of nine that she received from a

variety of suitors, including his West Point friend, A.P. Hill.

Ellen accepted Hill's proposal in 1856, but her family did not approve

and he withdrew. In

June

1854, McClellan was sent on a secret reconnaissance mission to

Santo Domingo at the behest of Jefferson Davis. McClellan assessed

local defensive capabilities for the secretary. (The information was

not used until 1870, when President Ulysses S. Grant

unsuccessfully attempted to annex the Dominican

Republic.)

Davis was beginning to treat McClellan almost as a

protégé, and his next assignment was to assess the

logistical readiness of various railroads in the United States, once

again with an eye toward planning for the transcontinental railroad. In March 1855, McClellan was

promoted to captain and assigned to the 1st U.S. Cavalry regiment. Because

of his political connections and his mastery of French, McClellan

received the assignment to be an official observer of the European

armies in the Crimean War in

1855. Traveling widely, and interacting with the highest military

commands and royal families, McClellan observed the siege of Sevastopol.

Upon

his return to the United States in 1856 he requested assignment in

Philadelphia to prepare his report, which contained a critical analysis

of the siege and a lengthy description of the organization of the

European armies. He also wrote a manual on cavalry tactics that

was based on Russian cavalry regulations. A notable failure of the

observers, including McClellan, was that they neglected to explain the

importance of the emergence of rifled muskets in the Crimean War, and how

that would require fundamental changes in tactics for the coming Civil

War. The Army adopted McClellan's cavalry

manual and also his design for a saddle, the "McClellan

Saddle", which he claimed to

have seen used by Hussars in Prussia and Hungary. It became standard issue for

as long as the U.S. horse cavalry existed and is currently used for

ceremonies. McClellan

resigned

his commission January 16, 1857, and, capitalizing on his

experience with railroad assessment, became chief engineer and vice

president of the Illinois

Central Railroad and also president of the Ohio and

Mississippi Railroad in

1860. He performed well in both jobs, expanding the Illinois Central

toward New Orleans and helping the Ohio and

Mississippi recover from the Panic of 1857.

But

despite his successes and lucrative salary ($10,000 per year), he

was frustrated with civilian employment and continued to study

classical military strategy assiduously. During the Utah War against the Mormons,

he considered rejoining the Army. He also considered service as a filibuster in support of Benito

Juárez in

Mexico. Before

the outbreak of Civil War, McClellan became active in politics,

supporting the presidential campaign of Democrat Stephen A.

Douglas in the 1860 election.

He claimed to have defeated an attempt at vote fraud by Republicans by ordering the delay of a

train that was carrying men to vote illegally in another county,

enabling Douglas to win the county. In

October 1859 McClellan was able to resume his courtship of Ellen Marcy,

and they were married in Calvary Church, New York City, on May 22, 1860. At

the

start of the Civil War, McClellan's knowledge of what was called

"big war science" and his railroad experience implied he would excel at

military logistics. This placed him in great demand as the Union mobilized.

The governors of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, the three largest

states of the Union, actively pursued him to command their states'

militia. Ohio Governor William Dennison was the most persistent, so

McClellan was commissioned a major general of volunteers and took

command of the Ohio militia on April 23, 1861. Unlike some of his

fellow Union officers who came from abolitionist families,

he was opposed to federal interference with slavery. So some of his

Southern colleagues approached him informally about siding with the

Confederacy, but he could not accept the concept of secession. On

May 3 McClellan re-entered federal service by being named commander of

the Department of

the Ohio,

responsible for the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and, later,

western Pennsylvania, western Virginia, and Missouri. On May 14, he was

commissioned a major general in the regular army. At age 34 he now

outranked everyone in the Army other than Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott,

the general in chief. McClellan's rapid promotion was partly because of

his acquaintance with Salmon P. Chase, Treasury

Secretary and

former Ohio governor and senator. As

McClellan scrambled to process the thousands of men who were

volunteering for service and to set up training camps, he also set his

mind toward grand strategy. He wrote a letter to Gen. Scott on April

27, four days after assuming command in Ohio, that was the first

proposal for a unified strategy for the war. It contained two

alternatives, both with a prominent role for himself as commander. The

first called for 80,000 men to invade Virginia through the Kanawha

Valley toward Richmond.

The second called for those same men to drive south instead across the

Ohio River into Kentucky and Tennessee. Scott dismissed both plans as

being logistically infeasible. Although he complimented McClellan and

expressed his "great confidence in your intelligence, zeal, science,

and energy", he replied by letter that the 80,000 men would be better

used on a river-based expedition to control the Mississippi

River and split the Confederacy, accompanied by

a strong Union

blockade of

Southern ports. This plan, which would have demanded considerable

patience on the part of the Northern public, was derided in newspapers

as the Anaconda

Plan,

but eventually proved to be the successful outline used to prosecute

the war. Relations between the two generals became increasingly

strained over the summer and fall. McClellan's

first military operations were to occupy the area of western Virginia that wanted to remain in

the Union and later became the state of West Virginia.

He had received intelligence reports on May 26 that the critical Baltimore and

Ohio Railroad bridges

in

that portion of the state were being burned. As he quickly

implemented plans to invade the region, he triggered his first serious

political controversy by proclaiming to the citizens there that his

forces had no intentions of interfering with personal

property — including slaves. "Notwithstanding all that has been said by

the traitors to induce you to believe that our advent among you will be

signalized by interference with your slaves, understand one thing

clearly — not only will we abstain from all such interference but we

will

on the contrary with an iron hand, crush any attempted insurrection on

their part." He quickly realized that he had overstepped his bounds and

apologized by letter to President Lincoln. The controversy was not that

his proclamation was diametrically opposed to the administration's

policy at the time, but that he was so bold in stepping beyond his

strictly military role. His forces moved rapidly into the area

through Grafton and were victorious at the tiny skirmish

called the Battle

of Philippi Races, arguably

the first land conflict of the war. His first personal command in

battle was at Rich

Mountain,

which he also won, but only after displaying a strong sense of caution

and a reluctance to commit reserve forces that would be his hallmark

for the rest of his career. His subordinate commander, William

S. Rosecrans, bitterly

complained that his attack was not reinforced as McClellan had agreed. Nevertheless, these two minor victories

propelled McClellan to the status of national hero. The New York Herald entitled an article about him, "Gen.

McClellan, the Napoleon of the Present War." After the

defeat of the Union forces at Bull Run on

July 21, 1861, Lincoln summoned McClellan from West Virginia, where

McClellan had given the North the only actions thus far having a

semblance of military victories. He traveled by special train on the

main Pennsylvania line from Wheeling through Pittsburgh, Philadelphia,

and Baltimore,

and on to Washington, D.C.,

and was overwhelmed by enthusiastic crowds that met his train along the

way. Carl Sandburg wrote,

"McClellan was the man of the hour, pointed to by events, and chosen by

an overwhelming weight of public and private opinion." On

July 26, the day he reached the capital, McClellan was appointed

commander of the Military Division of the Potomac, the main Union force

responsible for the defense of Washington. On August 20, several

military units in Virginia were consolidated into his department and he

immediately formed the Army of the

Potomac, with himself as its first commander. He reveled in his newly

acquired power and fame: I

find myself in a new and strange position here — Presdt, Cabinet, Genl

Scott & all deferring to me — by some strange operation of magic I

seem to have become the power

of the land. ... I almost think that were I to win some small success

now I could become Dictator or anything else that might please me — but

nothing of that kind would please me — therefore I won't be Dictator. Admirable

self-denial! – George B. McClellan, letter to Ellen, July

26, 1861 McClellan's

antipathy to emancipation added to the pressure on him, as he received

bitter criticism from Radical

Republicans in

the government. He viewed

slavery as an institution recognized in the Constitution,

and entitled to federal protection wherever it existed (Lincoln held

the same public position until August 1862). McClellan's

writings after the war were typical of many Northerners: "I confess to

a prejudice in favor of my own race, & can't learn to like the odor

of either Billy goats or niggers." But in November 1861, he wrote to

his wife, "I will, if successful, throw my sword onto the scale to

force an improvement in the condition of those poor blacks." He later

wrote that had it been his place to arrange the terms of peace, he

would have insisted on gradual emancipation, guarding the rights of

both slaves and masters, as part of any settlement. But he made no

secret of his opposition to the radical Republicans. He told Ellen, "I

will not fight for the abolitionists." This placed him at an obvious

handicap because many politicians running the government believed that

he was attempting to implement the policies of the opposition party. The

immediate

problem with McClellan's war strategy was that he was

convinced the Confederates were ready to attack him with overwhelming

numbers. On August 8, believing that the Confederates had over 100,000

troops facing him (in contrast to the 35,000 they actually deployed at

Bull Run a few weeks earlier), he declared a state of emergency in the

capital. By August 19, he estimated 150,000 enemy to his front.

McClellan's future campaigns would be strongly influenced by the

overblown enemy strength estimates of his secret service chief,

detective Allan Pinkerton,

but

in August 1861, these estimates were entirely McClellan's own. The

result was a level of extreme caution that sapped the initiative of

McClellan's army and caused great condemnation by his government.

Historian and biographer Stephen W. Sears has called McClellan's

actions "essentially sound" if he had been as outnumbered as he

believed, but McClellan in fact rarely had less than a two-to-one

advantage over his opponents in 1861 and 1862. That fall, for example,

Confederate forces ranged from 35,000 to 60,000, whereas the Army of

the Potomac in September numbered 122,000 men; in early December

170,000; by year end, 192,000. The

dispute with Scott would become very personal. Scott (along with many

in the War Department) was outraged that McClellan refused to divulge

any details about his strategic planning, or even mundane details such

as troop strengths and dispositions. (For his part, McClellan claimed

not to trust anyone in the administration to keep his plans secret from

the press, and thus the enemy.) During disagreements about defensive

forces on the Potomac River, McClellan wrote to his wife on August 10

in a manner that would characterize some of his more private

correspondence: "Genl Scott is the great obstacle — he will not

comprehend the danger & is either a traitor, or an incompetent. I

have to fight my way against him." Scott

became so disillusioned over his relationship with the young general

that he offered his resignation to President Lincoln, who initially

refused to accept it. Rumors traveled through the capital that

McClellan might resign, or instigate a military coup, if Scott were not

removed. Lincoln's Cabinet met on October 18 and agreed to accept

Scott's resignation for "reasons of health."

On November 1, 1861, Winfield Scott retired

and McClellan became general in chief of all the Union armies. The

president expressed his concern about the "vast labor" involved in the

dual role of army commander and general in chief, but McClellan

responded, "I can do it all."

Lincoln,

as

well as many other leaders and citizens of the northern states,

became increasingly impatient with McClellan's slowness to attack the

Confederate forces still massed near Washington. The Union defeat at

the minor Battle of

Ball's Bluff near Leesburg in October added to the

frustration and indirectly damaged McClellan. In December, the Congress

formed a Joint Committee

on the Conduct of the War,

which became a thorn in the side of many generals throughout the war,

accusing them of incompetence and, in some cases, treason. McClellan

was called as the first witness on December 23, but he contracted typhoid fever and

could not attend. Instead, his subordinate officers testified, and

their candid admissions that they had no knowledge of specific

strategies for advancing against the Confederates raised many calls for

McClellan's dismissal.

McClellan

further damaged his reputation by his insulting insubordination to his

commander-in-chief. He privately referred to Lincoln, whom he had known

before the war as a lawyer for the Illinois Central, as "nothing more

than a well-meaning baboon", a "gorilla", and "ever unworthy of ... his

high position." On

November 13, he snubbed the president, visiting at McClellan's house,

by making him wait for 30 minutes, only to be told that the general had

gone to bed and could not see him. On

January

10, Lincoln met with top generals (McClellan did not attend)

and directed them to formulate a plan of attack, expressing his

exasperation with General McClellan with the following remark: "If

General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow

it for a time." On

January 12, 1862, McClellan was summoned to the White House, where the

Cabinet demanded to hear his war plans. For the first time, he revealed

his intentions to transport the Army of the Potomac by ship to Urbanna, Virginia,

on the Rappahannock

River,

outflanking the Confederate forces near Washington, and proceeding

50 miles (80 km) overland to capture Richmond. He refused to give

any specific details of the proposed campaign, even to his friend,

newly appointed War Secretary Edwin M. Stanton.

On January 27, Lincoln issued an order that required all of his armies

to begin offensive operations by February 22, Washington's

birthday. On January 31, he issued a supplementary order for the

Army of the Potomac to move overland to attack the Confederates at Manassas

Junction and Centreville.

McClellan

immediately replied with a 22-page letter objecting in detail

to the president's plan and advocating instead his Urbanna plan, which

was the first written instance of the plan's details being presented to

the president. Although Lincoln believed his plan was superior, he was

relieved that McClellan finally agreed to begin moving, and reluctantly

approved. On March 8, doubting McClellan's resolve, Lincoln again

interfered with the army commander's prerogatives. He called a council of war at

the White House in which McClellan's subordinates were asked about

their confidence in the Urbanna plan. They expressed their confidence

to varying degrees. After the meeting, Lincoln issued another order,

naming specific officers as corps commanders to report to McClellan

(who had been reluctant to do so prior to assessing his division

commanders' effectiveness in combat, even though this would have meant

his direct supervision of twelve divisions in the field). Two

more crises would hit McClellan before he could implement his plans.

The Confederate forces under General Joseph E.

Johnston withdrew from their positions before Washington,

assuming new positions south of

the Rappahannock, which completely nullified the Urbanna strategy.

McClellan retooled his plan so that his troops would disembark at Fort Monroe, Virginia,

and advance up the Virginia

Peninsula to

Richmond, an operation that would be known as the Peninsula

Campaign.

However, McClellan came under extreme criticism from the press and the

Congress when it was found that Johnston's forces had not only slipped

away unnoticed, but had for months fooled the Union Army through the

use of logs painted black to appear as cannons, nicknamed Quaker Guns.

The

Congress's joint committee visited the abandoned Confederate lines

and radical Republicans introduced a resolution demanding the dismissal

of McClellan, but it was narrowly defeated by a parliamentary maneuver. The second crisis was the

emergence of the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia,

which threw Washington into a panic and made naval support operations

on the James River seem problematic. On

March 11, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief, leaving

him in command of only the Army of the Potomac, ostensibly so that

McClellan would be free to devote all his attention to the move on

Richmond. Lincoln's order was ambiguous as to whether McClellan might

be restored following a successful campaign. In fact, his position was

not filled by another officer. Lincoln, Stanton, and a group of

officers called the "War Board" directed the strategic actions of the

Union armies that spring. Although McClellan was assuaged by supportive

comments Lincoln made to him, in time he saw the change of command very

differently, describing it as a part of an intrigue "to secure the

failure of the approaching campaign." McClellan's

army began to sail from Alexandria on

March 17. It was an armada that dwarfed all previous American

expeditions, transporting 121,500 men, 44 artillery batteries, 1,150

wagons, over 15,000 horses, and tons of equipment and supplies. An

English observer remarked that it was the "stride of a giant." The army's advance from Fort Monroe up the Virginia

Peninsula proved to be slow. McClellan's plan for a rapid

seizure of Yorktown was

foiled when he discovered that the Confederates had fortified a line

across the Peninsula, causing him to decide on a siege of the city,

which required considerable preparation. McClellan

continued

to believe intelligence reports that credited the

Confederates with two or three times the men they actually had. Early

in the campaign, Confederate General John B. "Prince

John" Magruder defended

the

Peninsula against McClellan's advance with a vastly smaller force.

He created a false impression of many troops behind the lines and of

even more troops arriving. He accomplished this by marching small

groups of men repeatedly past places where they could be observed at a

distance or were just out of sight, accompanied by great noise and

fanfare. During

this time, General Johnston was able to provide Magruder with

reinforcements, but even then there were far fewer troops than

McClellan believed were opposite him. After

a

month of preparation, just before he was to assault the Confederate

works at Yorktown, McClellan learned that Johnston had withdrawn up the

Peninsula towards Williamsburg.

McClellan

was thus required to give chase without any benefit of the

heavy artillery so carefully amassed in front of Yorktown. The Battle of

Williamsburg on

May 5 is considered a Union victory — McClellan's first — but the

Confederate army was not destroyed and a bulk of their troops were

successfully moved past Williamsburg to Richmond's outer defenses while

it was waged, and over the next several days.

McClellan had also placed hopes on a simultaneous naval approach to

Richmond via the James River.

That approach failed following the Union Navy's defeat at the Battle of

Drewry's Bluff,

about 7 miles (11 km) downstream from the Confederate capital, on

May 15. Basing artillery on a strategic bluff high above a bend in the

river, and sinking boats to create an impassable series of obstacles in

the river itself, the Confederates had effectively blocked this

potential approach to Richmond.

McClellan's

army cautiously inched towards Richmond over the next three weeks,

coming to within four miles (6 km) of it. He established a supply base

on the Pamunkey River (a navigable tributary of

the York River)

at White House

Landing where the Richmond and

York River Railroad extending

to Richmond crossed, and commandeered the railroad,

transporting steam

locomotives and

rolling stock to the site by barge. On

May

31, as McClellan planned an assault, his army was surprised by a

Confederate attack. Johnston saw that the Union army was split in half

by the rain-swollen Chickahominy

River and hoped

to defeat it in

detail at Seven Pines and

Fair Oaks. McClellan was unable to command the army personally because

of a recurrence of malarial fever, but his subordinates were able to

repel the attacks. Nevertheless, McClellan received criticism from

Washington for not counterattacking, which some believed could have

opened the city of Richmond to capture. Johnston was wounded in the

battle, and General Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Army of

Northern Virginia.

McClellan spent the next three weeks repositioning his troops and

waiting for promised reinforcements, losing valuable time as Lee

continued to strengthen Richmond's defenses. At the end of June, Lee began a series of

attacks that became known as the Seven

Days Battles. The first major

battle, at Mechanicsville, was poorly coordinated by Lee and his

subordinates and caused heavy

casualties for little tactical gain. But the battle had significant

impact on McClellan's nerve. The surprise appearance of Maj. Gen. Stonewall

Jackson's troops in the

battle (when they had last been reported to be many miles away in the Shenandoah

Valley)

convinced McClellan that he was even more significantly outnumbered

than he had assumed. (He reported to Washington that he faced 200,000

Confederates, but there were actually 85,000.)

As

Lee continued his offensive at Gaines' Mill to

the east, McClellan played a passive role, taking no initiative and

waiting for events to unfold. He kept two thirds of his army out of

action, fooled again by Magruder's theatrical diversionary tactics. That night, he decided to

withdraw his army to a safer base, well below

Richmond, on a portion of the James River that was under control of the

Union Navy. In doing so, he may have unwittingly saved his army. Lee

had assumed that the Union army would withdraw to the east toward its

existing supply base and McClellan's move to the south delayed Lee's

response for at least 24 hours. But

McClellan was also tacitly acknowledging that he would no longer be

able to invest Richmond,

the object of his campaign; the heavy siege artillery required would be

almost impossible to transport without the railroad connections

available from his original supply base on the York River. In a

telegram to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton,

reporting

on these events, McClellan blamed the Lincoln administration

for his reversals. "If I save this army now, I tell you plainly I owe

no thanks to you or to any other persons in Washington. You have done

your best to sacrifice this army." Fortunately

for McClellan's immediate career, Lincoln never saw that inflammatory

statement (at least at that time) because it was censored by the War

Department telegrapher. McClellan

was

also fortunate that the failure of the campaign left his army

mostly intact, because he was generally absent from the fighting and

neglected to name a second-in-command to control his retreat. Military historian Stephen W.

Sears wrote, "When he deserted his army on the Glendale and Malvern Hill battlefields

during the Seven Days, he was guilty of dereliction of duty. Had the

Army of the Potomac been wrecked on either of these fields (at Glendale

the possibility had been real), that charge under the Articles of War

would likely have been brought against him." (During

Glendale, McClellan was five miles (8 km) away behind Malvern

Hill, without telegraph communications and too distant to command the

army. During the battle of Malvern Hill, he was on a gunboat, the U.S.S. Galena,

which at one point was ten miles (16 km) away down the James River. During both battles, effective

command of the army fell to his friend and V Corps commander Brigadier General Fitz John Porter.

When the public heard about the Galena,

it was yet another enormous embarrassment, comparable to the Quaker

Guns at Manassas. Editorial cartoons during the 1864

presidential campaign would

lampoon McClellan for preferring the safety of a ship while a battle

was fought in the distance.) McClellan

was

reunited with his army at Harrison's Landing on the James. Debates

were held as to whether the army should be evacuated or attempt to

resume an offensive toward Richmond. McClellan maintained his

estrangement from Abraham Lincoln by his continuous call for

reinforcements and by writing a lengthy letter in which he proposed

strategic and political guidance for the war, continuing his opposition

to abolition or seizure of slaves as a tactic. He concluded by implying

he should be restored as general in chief, but Lincoln responded by

naming Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck to the post without

consulting, or even informing, McClellan. Lincoln and Stanton also

offered command of the Army of the Potomac to Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside,

who refused the appointment. Back in Washington, a reorganization of

units created the Army

of Virginia under Maj. Gen. John

Pope,

who was directed to advance towards Richmond from the northeast.

McClellan resisted calls to reinforce Pope's army and delayed return of

the Army of the Potomac from the Peninsula enough so that the

reinforcements arrived while the Northern

Virginia Campaign was

already underway. He wrote to his wife before the battle, "Pope will be

thrashed ... & be disposed of [by Lee]. ... Such a villain as he is

ought to bring defeat upon any cause that employs him." Lee

had assessed McClellan's offensive nature and gambled on removing

significant units from the Peninsula to attack Pope, who was beaten

decisively at Second

Bull Run in August. After

the defeat of Pope at Second Bull Run, President Lincoln reluctantly

returned to the man who had mended a broken army before. He realized

that McClellan was a strong organizer and a skilled trainer of troops,

able to recombine the units of Pope's army with the Army of the Potomac

faster than anyone. On September 2, 1862, Lincoln named McClellan to

command "the fortifications of Washington, and all the troops for the

defense of the capital." The appointment was controversial in the

Cabinet, a majority of whom signed a petition declaring to the

president "our deliberate opinion that, at this time, it is not safe to

entrust to Major General McClellan the command of any Army of the

United States." The

president admitted that it was like "curing the bite with the hair of

the dog." But Lincoln told his secretary, John Hay, "We must use what

tools we have. There is no man in the Army who can man these

fortifications and lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as

he. If he can't fight himself, he excels in making others ready to

fight."

Northern

fears of a continued offensive by Robert E. Lee were realized when he

launched his Maryland

Campaign on

September 4, hoping to arouse pro-Southern sympathy in the slave state

of Maryland.

McClellan's

pursuit began on September 5. He marched toward Maryland

with six of his reorganized corps, about 84,000 men, while leaving two

corps behind to defend Washington. McClellan's

reception in

Frederick, Maryland, as he marched towards Lee's army, was

described by the correspondent for Harper's

Magazine: The

General rode through the town on a trot, and the street was filled six

or eight deep with his staff and guard riding on behind him. The

General had his head uncovered, and received gracefully the salutations

of the people. Old ladies and men wept for joy, and scores of beautiful

ladies waved flags from the balconies of houses upon the street, and

their joyousness seemed to overcome every other emotion. When the

General came to the corner of the principal street the ladies thronged

around him. Bouquets, beautiful and fragrant, in great numbers were

thrown at him, and the ladies crowded around him with the warmest good

wishes, and many of them were entirely overcome with emotion. I have

never witnessed such a scene. The General took the gentle hands which

were offered to him with many a kind and pleasing remark, and heard and

answered the many remarks and compliments with which the people

accosted him. It was a scene which no one could forget — an event of a

lifetime. Lee

divided his forces into multiple columns, spread apart widely as he

moved into Maryland and also maneuvered to capture the federal arsenal

at Harpers Ferry.

This

was a risky move for a smaller army, but Lee was counting on his

knowledge of McClellan's temperament. He told one of his generals, "He

is an able general but a very cautious one. His army is in a very

demoralized and chaotic condition, and will not be prepared for

offensive operations — or he will not think it so — for three or four

weeks. Before that time I hope to be on the Susquehanna." This

was not a completely accurate assessment, but McClellan's army was

moving lethargically, averaging only 6 miles (9.7 km) a day. However,

Little Mac soon received a miraculous break of fortune. Union soldiers

accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders that divided his army and

delivered them to McClellan's headquarters in Frederick on September

13. Upon realizing the intelligence value of this discovery, McClellan

threw up his arms and exclaimed, "Now I know what to do!" He waved the

order at his old Army friend, Brig.

Gen. John

Gibbon,

and said, "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I

will be willing to go home." He telegraphed President Lincoln: "I have

the whole rebel force in front of me, but I am confident, and no time

shall be lost. I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will

be severely punished for it. I have all the plans of the rebels, and

will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency.

... Will send you trophies.". Despite

this

show of bravado, McClellan continued his cautious line. After

telegraphing to the president at noon on September 13, rather than

ordering his units to set out for the South Mountain passes

immediately, he ordered them to depart the following morning. The 18

hours of delay allowed Lee time to react, because he received

intelligence from a Confederate sympathizer that McClellan knew of his

plans. (The delay also doomed the federal garrison at Harpers Ferry

because the relief column McClellan sent could not reach them before

they surrendered to Stonewall Jackson.) In the Battle of South

Mountain,

McClellan's army was able to punch through the defended passes that

separated them from Lee, but also gave Lee enough time to concentrate

many of his men at Sharpsburg, Maryland.

The

Battle of South Mountain presented McClellan with an opportunity

for one of the great theatrical moments of his career, as historian

Sears describes: The

Union army reached Antietam Creek, to the east of Sharpsburg, on the

evening of September 15. A planned attack on September 16 was put off

because of early morning fog, allowing Lee to prepare his defenses with

an army less than half the size of McClellan's.

The Battle of

Antietam on

September 17, 1862, was the single bloodiest day in American military

history. The outnumbered Confederate forces fought desperately and

well. Despite significant advantages in manpower, McClellan was unable

to concentrate his forces effectively, which meant that Lee was able to

shift his defenders to parry each of three Union thrusts, launched

separately and sequentially against the Confederate left, center, and

finally the right. And McClellan was unwilling to employ his ample

reserve forces to capitalize on localized successes. Historian James M.

McPherson has

pointed out that the two corps McClellan kept in reserve were in fact

larger than Lee's entire force. The reason for McClellan's reluctance

was that, as in previous battles, he was convinced he was outnumbered. The

battle

was tactically inconclusive, although Lee technically was

defeated because he withdrew first from the battlefield and retreated

back to Virginia. McClellan wired to Washington, "Our victory was

complete. The enemy is driven back into Virginia." Yet there was

obvious disappointment that McClellan had not crushed Lee, who was

fighting with a smaller army with its back to the Potomac River.

Although McClellan's subordinates can claim their share of

responsibility for delays (such as Ambrose Burnside's

misadventures at Burnside Bridge) and blunders (Edwin V. Sumner's

attack

without reconnaissance), these were localized problems from which the

full army could have recovered. As with the decisive battles

in the Seven Days, McClellan's headquarters were too far to the rear to

allow his personal control over the battle. He made no use of his

cavalry forces for reconnaissance. He did not share his overall battle

plans with his corps commanders, which prevented them from using

initiative outside of their sectors. And he was far too willing to

accept cautious advice about saving his reserves, such as when a

significant breakthrough in the center of the Confederate line could

have been exploited, but Fitz John Porter is said to have told

McClellan, "Remember, General, I command the last reserve of the last

Army of the Republic." Despite

being a tactical draw, Antietam is considered a turning point of

the war and a victory for the Union because it ended Lee's strategic

campaign (his first invasion of the North) and it allowed President

Lincoln to issue the Emancipation

Proclamation on

September 22, taking effect on January 1, 1863. Although Lincoln had

intended to issue the proclamation earlier, he was advised by his

Cabinet to wait until a Union victory to avoid the perception that it

was issued out of desperation. The Union victory and Lincoln's

proclamation played a considerable role in dissuading the governments of France and Britain from recognizing the

Confederacy; some suspected they were planning to do so in the

aftermath of another Union defeat. McClellan had no prior

knowledge that the plans for emancipation rested on his battle

performance. When

McClellan failed to pursue Lee aggressively after Antietam, Lincoln

ordered that he be removed from command on November 5. Maj. Gen. Ambrose

Burnside assumed command of the Army of the

Potomac on November 7. McClellan

wrote to his wife, "Those in whose judgment I rely tell me that I

fought the battle splendidly and that it was a masterpiece of art. ...

I feel I have done all that can be asked in twice saving the country.

... I feel some little pride in having, with a beaten & demoralized

army, defeated Lee so utterly. ... Well, one of these days history will

I trust do me justice." Secretary

Stanton ordered McClellan to report to Trenton, New Jersey,

for

further orders, although none were issued. As the war progressed, there

were various calls to return Little Mac to an important command,

following the Union defeats at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville,

as Robert E. Lee moved north at the start of the Gettysburg

Campaign, and as Jubal Early

threatened

Washington in 1864. When Ulysses S. Grant became general in chief, he

discussed returning McClellan to an unspecified position. But all of

these opportunities were impossible, given the opposition within the

administration and the knowledge that McClellan posed a potential

political threat. McClellan worked for months on a lengthy report

describing his two major campaigns and his successes in organizing the

Army, replying to his critics and justifying his actions by accusing

the administration of undercutting him and denying him necessary

reinforcements. The War Department was reluctant to publish his report

because, just after completing it in October 1863, McClellan openly

declared his entrance to the political stage as a Democrat. McClellan

was nominated by the Democrats to run against Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 U.S.

presidential election. Following the example of Winfield Scott,

he

ran as a U.S. Army general still on active duty; he did not resign

his commission until election day, November 8, 1864. He supported

continuation of the war and restoration of the Union, but the party

platform, written by Copperhead Clement

Vallandigham of

Ohio, was opposed to this position. The platform called for an

immediate cessation of hostilities and a negotiated settlement with the

Confederacy. McClellan was forced to repudiate the platform, which made

his campaign inconsistent and difficult. He also was not helped by the

party's choice for vice president, George H.

Pendleton, a peace candidate from Ohio. The deep division in the party, the unity

of the Republicans (running

under the label "National Union Party"), and the military successes by

Union forces in the fall of 1864 doomed McClellan's candidacy. Lincoln

won the election handily, with 212 Electoral

College votes to 21 and a popular vote of

403,000, or 55%. While

McClellan was highly popular among the troops when he was commander,

they voted for Lincoln over him by margins of 3-1 or higher. Lincoln's

share of the vote in the Army of the Potomac was 70%. After

the

war, McClellan and his family departed for a lengthy trip to Europe

(from 1865 to 1868), during which he did not participate in politics. When

he returned, the Democratic Party expressed some interest in nominating

him for president again, but when it became clear that Ulysses S. Grant

would be the Republican candidate, this interest died. McClellan worked

on engineering projects in New York City and was offered the position

of president of the newly formed University of

California. McClellan

was

appointed chief engineer of the New York City Department of Docks

in 1870. Evidently the position did not demand his full-time attention

because, starting in 1872, he also served as the president of the Atlantic and

Great Western Railroad. He and his family returned to Europe

from 1873 to 1875.

In March 1877, McClellan was nominated by Governor Lucius Robinson to be the first Superintendent

of Public Works but

was rejected by the New York State

Senate as being

"incompetent for the position."

In

1877, McClellan was nominated by the Democrats for Governor of New

Jersey,

an action that took him by surprise because he had not expressed an

interest in the position. He was elected and served a single term from

1878 to 1881, a tenure marked by careful, conservative executive

management and minimal political rancor. The concluding chapter of his

political career was his strong support in 1884 for the election of Grover Cleveland.

He hoped to be named secretary of war in

Cleveland's cabinet, a position for which he was well suited, but

political rivals from New Jersey were able to block his nomination. McClellan's

final years were devoted to traveling and writing. He justified his

military career in McClellan’s Own Story, published posthumously

in 1887. He died unexpectedly at age 58 at Orange, New Jersey,

after

having suffered from chest pains for a few weeks. His final

words, at 3 a.m., October 29, 1885, were, "I feel easy now. Thank you."

He is buried at Riverview

Cemetery, Trenton, New Jersey. McClellan's son, George

B. McClellan, Jr. (1865 – 1940), was born in Dresden,

Germany, during the family's

first trip to Europe. Known within the family as Max, he was also a

politician, serving as a United

States Representative from New York State and as Mayor

of New York City from

1904 to 1909. McClellan's daughter, Mary ("May") (1861 – 1945),

married a French diplomat and spent much of her life abroad. His wife

Ellen died in Nice,

France, while visiting May at

"Villa Antietam." Neither Max nor May gave the McClellans any

grandchildren. The

New York Evening Post commented

in McClellan's obituary, "Probably no soldier who did so little

fighting has ever had his qualities as a commander so minutely, and we

may add, so fiercely discussed." This

fierce discussion has continued for over a century. McClellan is

usually ranked in the lowest tier of Civil War generals. However, the

debate over McClellan's ability and talents remains the subject of much

controversy among Civil War and military historians. He has been

universally praised for his organizational abilities and for his very

good relations with his troops. They referred to him affectionately as

"Little Mac"; others sometimes called him the "Young Napoleon". It has

been suggested that his reluctance to enter battle was caused in part

by an intense desire to avoid spilling the blood of his men.

Ironically, this led to failing to take the initiative against the

enemy and therefore passing up good opportunities for decisive

victories, which could have ended the war early, and thereby could have

spared thousands of soldiers who died in those subsequent battles.

Generals who proved successful in the war, such as Lee and Grant,

tended to be more aggressive and more willing to risk a major battle

even when all preparations were not perfect. McClellan himself summed

up his cautious nature in a draft of his memoirs: McClellan's

reluctance

to press his enemy aggressively was probably not a matter of

personal courage, which he demonstrated well enough by his bravery

under fire in the Mexican -

American War. Stephen Sears wrote, One

of the reasons that McClellan's reputation has suffered is because of

his own memoirs. Historian Allan Nevins wrote, "Students of history

must always be grateful McClellan so frankly exposed his own weaknesses

in this posthumous book." Doris Kearns

Goodwin claims

that a review of his personal correspondence during the war reveals a

tendency for self-aggrandizement and unwarranted self-congratulation. His

original draft was completed in 1881, but the only copy was destroyed

by fire. He began to write another draft of what would be published

posthumously, in 1887, as McClellan's

Own Story.

However, he died before it was half completed and his literary

executor, William C. Prime, editor of the pro-McClellan New York Journal of Commerce,

included excerpts from some 250 of McClellan's wartime letters to his

wife, in which it had been his habit to reveal his innermost feelings

and opinions in unbridled fashion. Robert

E.

Lee, on being asked (by his cousin, and recorded by his son) who was

the ablest general on the Union side during the late war, replied

emphatically: "McClellan, by all odds!" While

McClellan's

reputation has suffered over time, especially over the last

75 years, there is a small but intense cadre of American Civil War

historians who believe that the general has been poorly served on at

least four levels. First, McClellan proponents say that because the

general was a conservative Democrat with great personal charisma,

radical Republicans fearing his political potential deliberately

undermined his field operations. Second,

that as the radical Republicans were the true winners coming out of the

American Civil War, they were able to write its history, placing their

principal political rival of the time, McClellan, in the worst possible

light. Third,

that historians eager to jump on the bandwagon of Lincoln as America's

greatest political icon worked to outdo one another in shifting blame

for early military failures from Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M.

Stanton to McClellan. And

fourth, that Lincoln and Stanton deliberately undermined McClellan

because of his conciliatory stance towards the South, which might have

resulted in a less destructive end to the war had Richmond fallen as a

result of the Peninsula Campaign. Proponents

of this school claim that McClellan is criticized more for his

admittedly abrasive personality than for his actual field performance. Several geographic features and

establishments have been named for George B. McClellan. These include Fort

McClellan in Alabama, McClellan Butte in the Mount

Baker - Snoqualmie National Forest, where he traveled while conducting the

Pacific Railroad Survey in 1853, McClellan Street in North

Bend, Washington, McClellan

Street in South Philadelphia, McClellan Road in Cupertino, California, McClellan Elementary School

in Chicago, and a bronze equestrian

statue honoring General McClellan in Washington,

D.C. Another equestrian statue honors him in front of Philadelphia

City Hall.

During

the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to

his new army, and greatly improved its morale by his frequent trips to

review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in

which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the

adulation of his men. He

created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable,

consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7,200

artillerists. The

Army of the Potomac grew in number from 50,000 in July to 168,000 in

November and was considered by far the most colossal military unit the

world had seen in modern historical times. But

this was also a time of tension in the high command, as he continued to

quarrel frequently with the government and the general-in-chief, Lt.

Gen. Scott, on matters of strategy. McClellan rejected the tenets of

Scott's Anaconda Plan, favoring instead an overwhelming grand battle,

in the Napoleonic style.

He proposed that his army should be expanded to 273,000 men and 600

guns and "crush the rebels in one campaign." He favored a war that

would impose little impact on civilian populations and require no

emancipation of slaves.