<Back to Index>

- Physician Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch, 1843

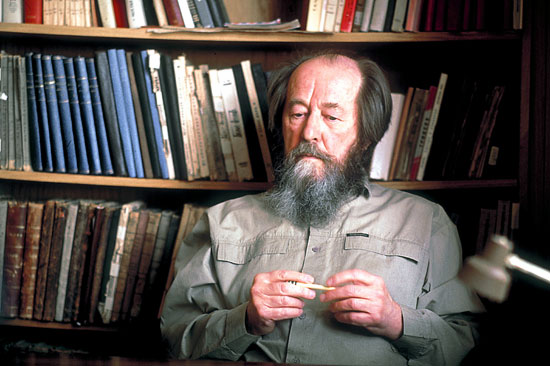

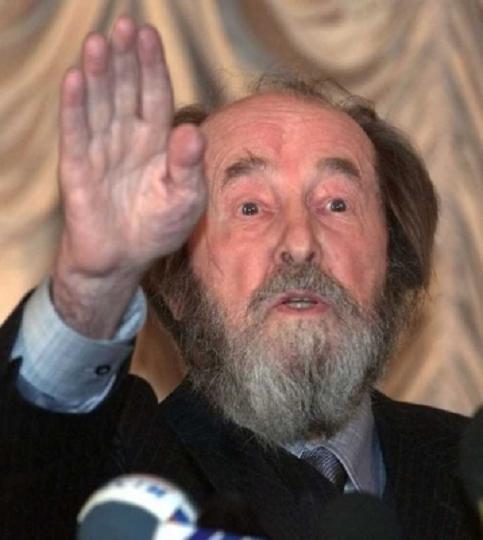

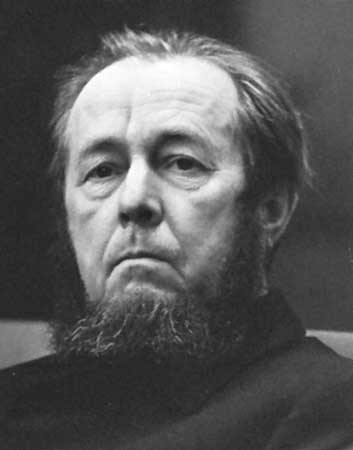

- Novelist Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn, 1918

- Russian Revolutionary Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov, 1857

PAGE SPONSOR

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn (Russian:Алекса́ндр Иса́евич Солжени́цын) (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian and Soviet novelist, dramatist, and historian. Through his writings he helped to make the world aware of the Gulag, the Soviet Union's forced labor camp system – particularly The Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, two of his best known works. Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970. He was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974 and returned to Russia in 1994. Solzhenitsyn was the father of Ignat Solzhenitsyn, a conductor and pianist.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born in Kislovodsk, RSFSR (now in Stavropol Krai, Russia). His mother was Ukrainian widow, Taisiya Solzhenitsyna (née Shcherbak), whose father had apparently risen from humble beginnings, as something of a self-made man. Eventually, he acquired a large estate in the Kuban region in the northern foothills of the Caucasus. During World War I, Taisiya went to Moscow to study. While there she met and married Isaakiy Solzhenitsyn, a young officer in the Imperial Russian Army of Cossack origins and fellow native of the Caucasus region. The family background of his parents is vividly brought to life in the opening chapters of August 1914, and later on in the Red Wheel novel cycle). In 1918, Taisia became pregnant with Aleksandr. Shortly after her pregnancy was confirmed, Isaakiy was killed in a hunting accident. Aleksandr was then raised by his widowed mother and aunt in lowly circumstances. His earliest years coincided with the Russian Civil War. By 1930 the family property had been turned into a collective farm. Later, Solzhenitsyn recalled that his mother had fought for survival and that they had to keep his father's background in the old Imperial Army a secret. His educated mother (who never remarried) encouraged his literary and scientific leanings and raised him in the Russian Orthodox faith; she died in 1944.

As early as 1936, Solzhenitsyn was developing the characters and concepts for a planned epic work on the First World War and the Russian Revolution. This eventually led to the novel August 1914 – some of the chapters he wrote then still survive. Solzhenitsyn studied mathematics at Rostov State University. At the same time he took correspondence courses from the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History, at this time heavily ideological in scope. As he himself makes clear, he did not question the state ideology or the superiority of the Soviet Union until he spent time in the camps.

On 7 April 1940, while at the university, Solzhenitsyn married a chemistry student Natalia Alekseevna Reshetovskaya. They divorced in 1952 (a year before his release from the Gulag); he remarried her in 1957 and they divorced again in 1972. The following year (1973) he married his second wife, Natalia Dmitrievna Svetlova, a mathematician who had a son from a brief prior marriage. He and Svetlova (b. 1939) had three sons: Yermolai (1970), Ignat (1972), and Stepan (1973).

During

World

War II Solzhenitsyn served as the commander of a sound ranging battery in the Red Army, was

involved in major action at the front, and twice decorated. A series of

writings published late in his life, including the early uncompleted

novel Love the

Revolution!, chronicle his WWII experience and his growing doubts

about the moral foundations of the Soviet regime. In

February

1945, while serving in East Prussia,

Solzhenitsyn

was arrested for writing derogatory comments in letters to

a friend, Nikolai Vitkevich, about the conduct of the war by Joseph Stalin,

whom

he called "Usatiy" ("one with mustachios,") "Khozyain"

("the

master"), and "Balabos", (Yiddish rendering of Hebrew baal ha-bayis for "master of the house"). He was accused of anti-Soviet

propaganda under Article 58 paragraph 10 of the Soviet

criminal code, and of "founding a hostile organization" under paragraph

11. Solzhenitsyn was taken to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow, where he was

beaten and interrogated. On 7 July 1945, he was sentenced in his

absence by Special Council

of the NKVD to

an eight-year term in a labor camp.

This

was the normal sentence for most crimes under Article 58 at the

time. The

first

part

of Solzhenitsyn's sentence was served in several different

work camps; the "middle phase," as he later referred to it, was spent

in a sharashka (i.e., a special scientific

research facility run by Ministry of State Security), where he met Lev Kopelev,

upon

whom he based the character of Lev

Rubin in his book The First Circle,

published

in

a self censored or "distorted" version in the West in 1968

(an English translation of the full version was eventually published by

Harper Perennial in October 2009). In

1950,

he was sent to a "Special Camp" for political prisoners. During

his imprisonment at the camp in the town of Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan, he worked as

a miner, bricklayer, and foundry foreman. His experiences at Ekibastuz

formed the basis for the book One Day in the

Life of Ivan Denisovich. One of his colleagues political

prisoners, Ion Moraru,

remembers

that Solzhenitsyn has written at Ekibastuz. While there he had a tumor

removed, although his cancer was not diagnosed at the time. In

March 1953 after the expiry of Solzhenitsyn's sentence, he was sent to

internal exile for life at Kok-Terek in southern Kazakhstan, as was

common for political prisoners. His undiagnosed cancer spread until, by

the end of the year, he was close to death. However, in 1954, he was

permitted to be treated in a hospital in Tashkent, where his tumor went into remission.

His experiences there became the basis of his novel Cancer Ward and

also found an echo in the short story "The right hand." It was during

this decade of imprisonment and exile that Solzhenitsyn abandoned Marxism and developed the philosophical and

religious positions of his later life; this turn has some interesting

parallels to Dostoevsky's

time in Siberia and his quest for faith a hundred years earlier.

Solzhenitsyn gradually turned into a philosophically - minded Christian

as a result of his experience in prison and the camps. He

repented for some of his actions as a Red Army captain, and in prison

compared himself to the perpetrators of the Gulag: "I remember myself

in my captain's shoulder boards and the forward march of my battery

through East Prussia, enshrouded in fire, and I say: 'So were we any

better?'" His transformation is described at some length in the fourth

part of The Gulag

Archipelago ("The Soul and Barbed Wire"). The

narrative poem The Trail (written

without benefit of pen or paper in prison and camps between 1947 and

1952) and the twenty-eight poems composed in prison, forced labor camp,

and exile also provide crucial material for understanding

Solzhenitsyn's intellectual and spiritual odyssey during this period.

These "early" works, largely unknown in the West, were published for

the first time in Russian in 1999 and excerpted in English in 2006. After Khrushchev's

Secret Speech in

1956 Solzhenitsyn was freed from exile and exonerated. After his return

to European Russia, Solzhenitsyn was, while teaching at a secondary

school during the day, spending his nights secretly engaged in writing.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he wrote, "during all the years

until 1961, not only was I convinced I should never see a single line

of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any

of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I

feared this would become known." In

the

1960s while he was publicly known to be writing Cancer Ward, he was

simultaneously writing The

Gulag

Archipelago. The KGB found out about this.

Finally, when he was 42 years old, he approached Alexander

Tvardovsky, a poet and the chief editor of the Noviy Mir magazine, with the manuscript of One Day in the Life of

Ivan Denisovich. It was published in edited form in 1962, with the

explicit approval of Nikita

Khrushchev,

who defended it at the presidium of the Politburo hearing on whether to

allow its publishing, and added: "There's a Stalinist in each of you;

there's even a Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil." The book became an instant hit

and sold-out everywhere. During Khrushchev's tenure, One Day in the Life of

Ivan Denisovich was

studied in schools in the Soviet Union as were three more short works

of Solzhenitsyn's, including his acclaimed short story Matryona's Home,

were published in 1963. These would be the last of his works published

in the Soviet Union until 1990. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich brought

the Soviet system of prison labor to the attention of the West. It

caused as much of a sensation in the Soviet Union as it did in the

West — not only by its striking realism and candour, but also because

it

was the first major piece of Soviet literature since the twenties on a

politically charged theme, written by a non-party member, indeed a man

who had been to Siberia for "libelous speech" about the leaders, and

yet its publication had been officially permitted. In this sense, the

publication of Solzhenitsyn's story was an almost unheard of instance

of free, unrestrained discussion of politics through literature. Most

Soviet readers realized this, but after Khrushchev had been ousted from

power in 1964, the time for such raw exposing works came quietly, but

perceptibly, to a close. Solzhenitsyn

made

an unsuccessful attempt, with the help of Tvardovsky, to get his

novel, The Cancer

Ward, legally published in the Soviet Union. This had to get the

approval of the Union of Writers.

Though

some

there appreciated it, the work ultimately was denied

publication unless it was to be revised and cleaned of suspect

statements and anti-Soviet insinuations (this episode is recounted and

documented in The Oak and the

Calf). The publishing of his work quickly stopped; as a

writer, he became a non-person,

and,

by 1965, the KGB had seized some of his

papers, including the manuscript of The

First

Circle. Meanwhile Solzhenitsyn continued to secretly and

feverishly work upon the most subversive of all his writings, the

monumental The Gulag

Archipelago.

The seizing of his novel manuscript first made him desperate and

frightened, but gradually he realized that it had set him free from the

pretenses and trappings of being an "officially acclaimed" writer,

something which had come close to second nature, but which was becoming

increasingly irrelevant. After

the

KGB had confiscated Solzhenitsyn's materials in Moscow, during 1965

– 1967 the preparatory drafts of The Gulag

Archipelago were turned into finished typescript in hiding

at his friends' homes in Estonia. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had befriended Arnold Susi,

a

lawyer and former Estonian Minister of Education in a Lubyanka Prison

cell. After completion, Solzhenitsyn's original handwritten script was

kept hidden from the KGB in Estonia by Arnold Susi's daughter Heli Susi

until the collapse of the Soviet Union. In

1969

Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Union of Writers. In 1970,

Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in

Literature. He could not receive the prize personally in Stockholm at

that time, since he was afraid he would not be let back into the Soviet

Union. Instead, it was suggested he should receive the prize in a

special ceremony at the Swedish embassy in Moscow. The Swedish

government refused to accept this solution, however, since such a

ceremony and the ensuing media coverage might upset the Soviet Union

and damage Sweden's relations with the superpower. Instead,

Solzhenitsyn received his prize at the 1974 ceremony after he had been

deported from the Soviet Union. The

Gulag

Archipelago was

composed

during 1958 – 1967. This work was a three volume, seven part

work on the Soviet prison camp system (Solzhenitsyn never had all seven

parts of the work in front of him at any one time). The Gulag Archipelago has

sold over thirty million copies in thirty five languages. It was based

upon Solzhenitsyn's own experience as well as the testimony of 256 former

prisoners and Solzhenitsyn's own research into the history of the penal

system. It discussed the system's origins from the founding of the

Communist regime, with Lenin himself having responsibility,

detailing interrogation procedures, prisoner transports, prison camp

culture, prisoner

uprisings

and revolts, and the practice of internal exile. The Gulag Archipelago's

rich

and

varied authorial voice, its unique weaving together of

personal testimony, philosophical analysis, and historical

investigation, and its unrelenting indictment of communist ideology made The Gulag Archipelago one of the most

consequential books of the twentieth century. The appearance of the book in

the West put the word gulag into the Western political

vocabulary and guaranteed swift retribution from the Soviet authorities. During this period, he was sheltered by

the cellist Mstislav

Rostropovich, who suffered

considerably for his support of Solzhenitsyn and was eventually forced

into exile himself. On 12 February 1974, Solzhenitsyn was

arrested and on the next day he was deported from the Soviet Union to Frankfurt,

West

Germany, and stripped of his Soviet citizenship. The KGB had found

the manuscript for the first part of The

Gulag

Archipelago and,

less than a week later, Yevgeny

Yevtushenko suffered

reprisals

for his support of Solzhenitsyn. U.S. military attache William Odom managed to smuggle out a

large portion of Solzhenitsyn's archive, including the author's

membership card for the Writers' Union and

Second World War military citations; Solzhenitsyn subsequently paid

tribute to Odom's role in his memoir "Invisible Allies" (1995).

In

Germany,

Solzhenitsyn lived in Heinrich

Böll's house in Cologne.

He then moved to Zurich,

Switzerland, before Stanford

University invited

him

to

stay in the United States to "facilitate your work, and to

accommodate you and your family." He stayed on the 11th floor of the Hoover Tower,

part

of the Hoover

Institution, before moving to Cavendish,

Vermont,

in 1976. He was given an honorary Literary Degree from Harvard

University in 1978

and on Thursday, 8 June 1978 he gave his Commencement

Address condemning,

among other things, materialism in modern western culture. Over

the

next 17 years, Solzhenitsyn worked on his cyclical history of the Russian

Revolution of 1917, The Red Wheel.

By

1992, four "knots" (parts) had been completed and he had also

written several shorter works. Despite

spending

two

decades in the United States, Solzhenitsyn did not become

fluent in spoken English. He had, however, been reading

English language literature since his teens, encouraged by his mother.

More

importantly, he resented the idea of becoming a media star and of

tempering his ideas or ways of talking in order to suit television.

Solzhenitsyn's warnings about the dangers of Communist aggression and

the weakening of the moral fiber of the West were generally well

received in Western conservative circles, alongside the tougher foreign

policy pursued by U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

At

the same time, liberals and secularists became increasingly

critical of what they perceived as his reactionary preference for Russian

patriotism and the Russian Orthodox religion. Solzhenitsyn also

harshly criticised what he saw as the ugliness and spiritual vapidity

of the dominant pop culture of

the modern West, including television and much of popular music:

"...the human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer than

those offered by today's mass living habits ... by TV stupor and

by intolerable music." Despite

his criticism of the "weakness" of the West, Solzhenitsyn always made

clear that he admired the political liberty which was one of the

enduring strengths of western democratic societies. In a major speech

delivered to the International Academy of Philosophy in Liechtenstein

on 14 September 1993, Solzhenitsyn implored the West not to "lose sight

of its own values, its historically unique stability of civic life

under the rule of law — a hard won stability which grants independence

and space to every private citizen." In

a series of writings, speeches, and interviews after his return to his

native Russia in 1994, Solzhenitsyn spoke about his admiration for the

local self-government he had witnessed first hand in Switzerland and

New England during his western exile. In

1990,

his

Soviet citizenship was restored, and, in 1994, he returned to

Russia with his wife, Natalia, who had become a United States citizen.

Their sons stayed behind in the United States (later, his oldest son

Yermolai returned to Russia to work for the Moscow office of a leading

management consultancy firm). From then until his death, he lived with

his wife in a dacha in Troitse-Lykovo

(Троице-Лыково) in west Moscow between the dachas once

occupied by Soviet leaders Mikhail Suslov and Konstantin

Chernenko. Following

the collapse of the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn called for a restoration

of the Russian monarchy. After

returning

to

Russia in 1994, Solzhenitsyn published eight two-part

short stories, a series of contemplative "miniatures" or prose poems, a

literary memoir on his years in the West (The Grain Between the

Millstones) among many other writings. All of Solzhenitsyn's sons became U.S.

citizens. One, Ignat, has achieved acclaim as a pianist and conductor in the United States.

The

most complete 30-volume edition of Solzhenitsyn's collected works is

soon to be published in Russia. The presentation of its first three

volumes, already in print, recently took place in Moscow. On 5 June

2007 then Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a decree conferring

on Solzhenitsyn the State Prize of

the Russian Federation for

his

humanitarian

work. Putin personally visited the writer at his home

on 12 June 2007 to present him with the award. Like his father,

Yermolai Solzhenitsyn has translated some of his father's works.

Stephan Solzhenitsyn lives and works in Moscow. Ignat

Solzhenitsyn is

the music director of The Chamber

Orchestra of Philadelphia. On

19 September 1974, Yuri Andropov approved a large scale

operation to discredit Solzhenitsyn and his family and cut his

communications with Soviet

dissidents. The plan was jointly approved by Vladimir

Kryuchkov, Philipp Bobkov,

and

Grigorenko (heads of First, Second and Fifth KGB Directorates). The

residencies in Geneva, London, Paris, Rome and other European cities

participated in the operation. Among other active measures, at least

three StB agents became translators

and secretaries of Solzhenitsyn (one of them translated the poem Prussian Nights),

keeping KGB informed regarding all contacts by Solzhenitsyn. KGB

sponsored a series of hostile books about Solzhenitsyn, most notably a

"memoir published under the name of his first wife, Natalia

Reshetovskaya, but probably mostly composed by Service", according to

historian Christopher

Andrew. Andropov also gave an order to create "an

atmosphere of distrust and suspicion between PAUK and

the people around him" by feeding him rumors that everyone in his

surrounding was a KGB agent and deceiving him in all possible ways.

Among other things, the writer constantly received envelopes with

photographs of car accidents, brain surgery and other frightening

illustrations. After the KGB harassment in Zurich, Solzhenitsyn settled

in Cavendish, Vermont, reduced communications with

others and surrounded his property with a barbed

wire fence.

His influence and moral authority for the West diminished as he became

increasingly isolated and critical of Western individualism. KGB and CPSU experts

finally concluded that he alienated American listeners by his

"reactionary views and intransigent criticism of the US way of life",

so no further active

measures would be required. In

his

book The Gulag

Archipelago Solzhenitsyn

states

that

he was recruited to report to the NKVD on fellow inmates

and was given a code name Vetrov, but due to his transfer to another

camp he was able to elude this duty and never produced a single report.

In

1976, after Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Union a

report signed by Vetrov surfaced. After a copy of the report was

obtained by Solzhenitsyn he published it together with a refutation in

the Los Angeles

Times (published

24 May 1976).

In

1978 the same report was published by journalist Frank Arnau in a socialist Western German magazine Neue Politik. However, according to

Solzhenitsyn the report is a fabrication by the KGB.

He claimed that the report is dated 20 January 1952 while all

Ukrainians were transferred to a separate camp on 6 January and they

had no relation to the uprising in Solzhenitsyn's camp on 22 January.

He also claimed that the only people who might in 1976 have access to a

"secret KGB archive" were KGB agents themselves. Solzhenitsyn also

requested Arnau to put the alleged document to a graphology test but Arnau refused. In 1990 the report was reproduced in

Soviet Voyenno-Istoricheskiy Zhurnal among the memoirs of L.A. Samutin, a former ROA soldier

and GULAG inmate who was an erstwhile supporter of Solzhenitsyn, but

later became his critic. According to Solzhenitzyn, publication of the

Samutin memoirs was canceled at the request of Samutin's widow, who

stated that the memoirs were in fact dictated by the KGB. Solzhenitsyn

declared

about the failing of atheism: Over

a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a

number of old people offer the following explanation for the great

disasters that had befallen Russia: "Men have forgotten God; that's why

all this has happened." Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years

working on the history of our revolution; in the process I have read

hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have

already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of

clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked

today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the

ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I

could not put it more accurately than to repeat: "Men have forgotten

God; that's why all this has happened." During his years in the west,

Solzhenitsyn was very active in the historical debate, discussing the

history of Russia, the Soviet

Union and

communism. He tried to

correct what he considered

to be western misconceptions. Solzhenitsyn

also published a two volume work on the history of Russian - Jewish

relations (Two Hundred Years Together 2001, 2002). This book

stirred controversy and caused Solzhenitsyn to be widely accused of anti-Semitism. The book became a

best seller in Russia. Solzhenitsyn

begins this work with a plea for "patient mutual comprehension" on the

part of Russians and Russian Jews. The author writes that the book was

conceived in the hope of promoting "mutually agreeable and fruitful

pathways for the future development of Russian - Jewish relations."

There

is sharp division on the allegation of anti-Semitism.

From Solzhenitsyn's own essay "Repentance and Self-Limitation in the

Life of Nations", he

calls for Russians and Jews alike to take moral responsibility for the

"renegades" from both communities who enthusiastically supported a

Marxist dictatorship after the October

Revolution. At the end of chapter 15, he writes that Jews must

answer for the

"revolutionary cutthroats" in their ranks just as Russian Gentiles must

repent "for the pogroms,

for those merciless arsonist peasants, for ... crazed revolutionary

soldiers." It is not, he adds, a matter of answering "before other

peoples, but to oneself, to one's consciousness, and before God."

Similarities

between Two Hundred

years together and an

antisemitic essay titled "Jews in the USSR and in the Future

Russia", attributed to Solzhenitsyn, has led to inference that he

stands behind the anti-Semitic passages. Solzhenitsyn himself claims

that the essay consists of manuscripts stolen from him, and then

manipulated, forty years ago. However,

according to the

historian Semyon Reznik,

textological

analyses have proven Solzhenitsyn's authorship.

In

1984 Solzhenitsyn was interviewed by Nikolay Kazantsev, a monarchist

Russo - Argentine journalist, for Nasha

Strana, a Russian language newspaper based in Buenos Aires.

In

the

interview he said: "We (Russia) are walking a narrow istmus

between Communists and the World Jewry. Neither is acceptable for us...

And I mean this not in the racial sense, but in the sense of the Jewry

as a certain world view. The Jewry is embodied in "Fevralism" (i.e.

democracy). Neither side is acceptable to us in the case the War breaks

out." He also described the United States as a "province of Israel". Russian dissident writer Vladimir

Voynovich, interviewed for Radio

Liberty on the first anniversary of Solzhenitsyn'

death, has alleged that

Solzhenitshyn harbored anti-Semitic sentiments all his life, as

attested by the 1964 manuscript he later developed into "200 Years

Together". Voynovich further alleged that Solzhenitsyn deliberately

concealed this anti-Semitism, because he knew this would have prevented

him from receiving the Nobel

Prize. In

some

of his later political writings, such as Rebuilding Russia (1990) and Russia in Collapse (1998),

Solzhenitsyn criticized the oligarchic excesses of the new Russian

'democracy,' while opposing any nostalgia for Soviet Communism. He

defended moderate and self-critical patriotism (as opposed to extreme

nationalism), argued for the indispensability of local self-government

to a free Russia, and expressed concerns for the fate of the 25 million

ethnic Russians in the "near abroad"

of

the

former Soviet Union. He also sought to protect the national

character of the Russian Orthodox church and fought against the

admission of Catholic priests and Protestant pastors to Russia from

other countries. For a brief period, he had his own TV show, where he

freely expressed his views. The show was cancelled because of low

ratings, but Solzhenitsyn continued to maintain a relatively high

profile in the media. Delivering

the

commencement

address at Harvard in 1978, he called the United

States spiritually weak and mired in vulgar materialism. Americans, he

said, speaking in Russian through a translator, suffered from a

"decline in courage" and a "lack of manliness." Few were willing to die

for their ideals, he said. He condemned both the United States

government and American society for its "hasty" capitulation in

Vietnam. He criticized the country's music as intolerable and attacked

its unfettered press, accusing it of violations of privacy. He said

that the West erred in measuring other civilizations by its own model.

While faulting Soviet society for denying fair legal treatment of

people, he also faulted the West for being too legalistic: "A society

which is based on the letter of the law and never reaches any higher is

taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human possibilities." Shortly after his death, professor Richard

Pipes,

a history professor at Harvard, wrote of him: "Solzhenitsyn blamed the

evils of Soviet communism on the West. He rightly stressed the European

origins of Marxism, but he never asked himself why Marxism in other

European countries led not to the gulag but to the welfare state. He

reacted with white fury to any suggestion that the roots of Leninism

and Stalinism could be found in Russia's past. His knowledge of Russian

history was very superficial and laced with a romantic sentimentalism.

While accusing the West of imperialism, he seemed quite unaware of the

extraordinary expansion of his own country into regions inhabited by

non-Russians. He also denied that Imperial Russia practiced censorship

or condemned political prisoners to hard labor, which, of course, was

absurd.".

In

his

1978

Harvard address, Solzhenitsyn argued over Russian culture,

that the West erred in "denying its autonomous character and therefore

never understood it". Solzhenitsyn

emphasized

the significantly more oppressive character of the Soviet totalitarian regime, in comparison to the Russian Empire of the House of Romanov.

He

asserted that Imperial Russia did not practice any real censorship in the style of the Soviet Glavlit, that political prisoners

typically were not always forced into labor camps, and

that the number of political prisoners and exiles was only one

ten-thousandth of those in the Soviet Union. He noted that the Tsar's

secret police, or Okhrana,

was only present in the three largest cities, and not at all in the Imperial

Russian Army.

In

a

speech commenorating the Vendée

Uprising, Solzhenitsyn compared Lenin's Bolsheviks with Jacobins of the French

Revolution. However, he commented that, while the French Reign of Terror ended with the execution of Maximilien

Robespierre, its Soviet equivalent raged unabated from 1917

until the Khrushchev thaw in the 1950s.

He

believed

that revolutionary violence comes from the teachings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,

arguing Marxism is violent. His conclusion

is that Marxist Governments will always be dictatorships, no matter

which country they exist in. According

to

Solzhenitsyn,

Russians were not the ruling nation in the Soviet

Union. He believed that all ethnic cultures have been oppressed in

favor of an atheistic Marxism. Russian culture was even more repressed

than any other culture in the Soviet Union, since the regime was more

afraid of ethnic uprisings among Russian Christians than among any

other ethnicity. Therefore, Solzhenitsyn argued, Russian nationalism and the Orthodox Church should not be regarded as a

threat by the West but rather as allies. Solzhenitsyn

said that for every country, great power status deforms and harms the

national character and that he has never wished great power status for

Russia. He rejected the view that the USA and Russia are natural

rivals, saying that before the [Russian] revolution, they were natural

allies and that during the American

Civil

War, Russia supported Lincoln and the North [in contrast to Britain and

France, which supported the Confederacy],

and then they were allies in the First World War. But beginning with

Communism, Russia ceased to exist and the confrontation was not at all

with Russia but with the Communist Soviet Union. Solzhenitsyn

criticized

the Allies for

not opening a new front against Nazi Germany in the west earlier in

World War II. This resulted in Soviet domination and oppression of the

nations of Eastern Europe.

Solzhenitsyn

claimed

the Western democracies apparently cared little

about how many died in the East, as long as they could end the war

quickly and painlessly for themselves in the West. While stationed in

East Prussia as an artillery officer, Solzhenitsyn witnessed war crimes

against the civilian German population by Soviet "liberators" as

the elderly were robbed of their meager possessions and women were

gang raped to death. He wrote a poem entitled "Prussian Nights"

about

these

incidents. In it, the first person narrator seems to

approve of the troops' crimes as revenge for German atrocities,

expressing his desire to take part in the plunder himself. The poem

describes the rape of a Polish woman whom the Red Army soldiers

mistakenly thought to be a German.

In his The Gulag

Archipelago Solzhenitsyn

rejected

the view that it was Stalin who created the Soviet totalitarian

state. He argued that it was Lenin who started the mass

executions, created a planned economy,

founded

the Cheka which would later be turned

into the KGB, and

started the system of labor camps later known as Gulag. Solzhenitsyn

was

the most prominent of the Nobel Laureate Mikhail

Sholokhov's many detractors. He alleged that the work which made

Sholokhov's international reputation, And Quiet Flows

the Don was

written by Fyodor Kryukov,

a Cossack and Anti-Bolshevik,

who

died in 1920, possibly in retaliation for Sholokhov scathing

opinion re One Day

in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Solzhenitsyn claimed that

Sholokhov found the manuscript and published it under his own name. These rumors first appeared

in the late 1920s, but an investigation upheld Sholokhov's authorship of And Quiet Flows the Don and the allegations were

denounced as malicious slander in Pravda.

A

1984 monograph by Geir Kjetsaa and others demonstrated

through statistical analyses that Sholokhov was indeed the likely

author of Don. And in 1987, several thousand pages of notes and

drafts of the work were discovered and authenticated. During

the second world war, Sholokhov's archive was destroyed in a bomb raid,

and only the fourth volume survived. Sholokhov had his friend Vassily

Kudashov, who was killed in the war, look after it. Following

Kudashov's death, his widow took possession of the manuscript, but she

never disclosed the fact of owning it. The manuscript was finally found

by the Institute of World Literature of Russia's Academy of Sciences in

1999 with assistance from the Russian Government. An analysis of the

novel has unambiguously proved Sholokhov's authorship. The writing

paper dates back to the 1920s: 605 pages are in Sholokhov's own hand,

and 285 are transcribed by his wife Maria and sisters. In 1973,

near the height of the Sino-Soviet

conflict, Solzhenitsyn sent a Letter

to

the Soviet Leaders to

a

limited

number of upper echelon Soviet officials. This work, which

was published for the general public in the Western world a year after

it was sent to its intended audience, beseeched the Soviet Union's

authorities to Give

them their ideology! Let the Chinese leaders glory in it for a while.

And for that matter, let them shoulder the whole sackful of

unfulfillable international obligations, let them grunt and heave and

instruct humanity, and foot all the bills for their absurd economics (a

million a day just to Cuba), and let them support terrorists and

guerrillas in the Southern Hemisphere too if they like. The main source

of the savage feuding between us will then melt away, a great many

points of today's contention and conflict all over the world will also

melt away, and a military clash will become a much remoter possibility

and perhaps won't

take place at all [author's

emphasis].

Once

in

America, Solzhenitsyn urged the United States to continue its

involvement in the Vietnam War.

In

his commencement address at Harvard University in 1978 (A World

Split Apart), Solzhenitsyn alleged that many in the U.S. did not

understand the Vietnam War.

He

rhetorically

asks if the American Anti-War Movement ever realized

the effects their actions had on Vietnam: "But members of the U.S.

antiwar movement wound up being involved in the betrayal of Far Eastern

nations, in a genocide and in the suffering today imposed on 30 million

people there. Do those convinced pacifists hear the moans coming from

there?" During his time in the United States,

Solzhenitsyn made several controversial public statements: notably, he

accused Pentagon

Papersleak Daniel

Ellsberg of treason. Solzhenitsyn

strongly

condemned the bombing of

Yugoslavia during

the Kosovo War,

saying

"there is no difference whatsoever between NATO and Hitler." Solzhenitsyn

has

stated that the ongoing Ukrainian effort to have the 1930s famine,

the Holodomor,

recognized

as an act of genocide

against the Ukrainian people is

in

fact historical

revisionism. According to Solzhenitsyn, the famine was caused by

the nature of the

Communist regime, under which all peoples suffered. As such it

was not an assault by the

Russian people against the Ukrainian people, and the wish to represent

it as such is only recent and politically motivated. Solzhenitsyn's views on this matter are

in line with those of several historians of the period (such as Dmitri

Volkogonov and Aleksandr

Bushkov) as well as the

official stance of the Russian Government. This view suggests that

policies of collectivization and

mass seizure of property that lead to the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s

were a result of the political (communist) and economic (favoring rapid

industrial growth over consumption) policies of the Soviet Union, and

not racial hatred against the Ukrainians.

Solzhenitsyn

died of heart failure near Moscow on 3 August 2008, at the age of 89. A burial service was held at Donskoy

Monastery, Moscow, on Wednesday, 6 August 2008. He was buried on the same

date at the place chosen by him in Donskoy necropolis. Russian

and world leaders paid tribute to Solzhenitsyn following his death.