<Back to Index>

- Mathematician János Bolyai, 1802

- Architect Josef Hoffmann, 1870

- Filipino Revolutionary Emilio Jacinto, 1875

PAGE SPONSOR

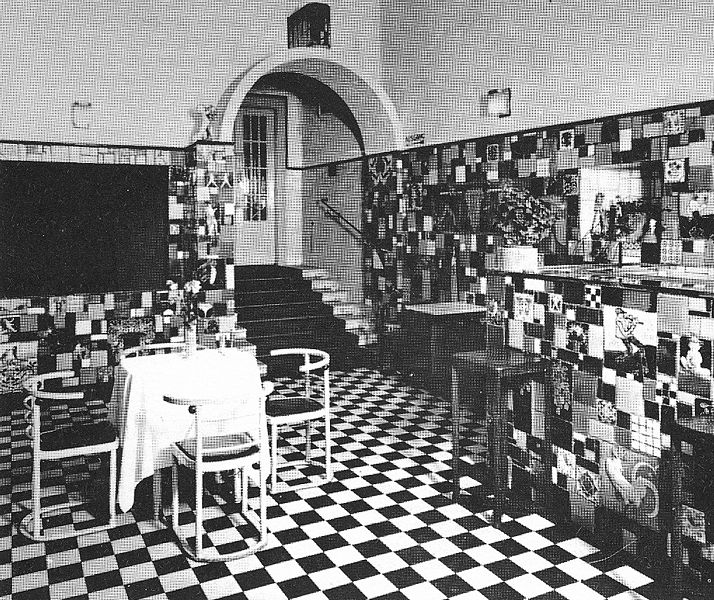

Josef Hoffmann (December 15, 1870, Brtnice, Moravia, now part of the Czech Republic – May 7, 1956, Vienna, Austria) was an Austrian architect and designer of consumer goods.

Hoffmann studied at the Higher State Crafts School in Brno beginning in 1887 and then worked with the local military planning authority in Würzburg. Thereafter he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna with Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer and Otto Wagner, graduating with a Prix de Rome in 1895. In Wagner's office, he met Joseph Maria Olbrich, and together they founded the Vienna Secession in 1897 along with artists Gustav Klimt, and Koloman Moser. Beginning in 1899, he taught at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. With the Secession, Hoffmann developed strong connections with other artists. He designed installation spaces for Secession exhibitions and a house for Moser which was built from 1901 - 1903. However, he soon left the Secession in 1905 along with other stylist artists due to conflicts with realist naturalists over differences in artistic vision and disagreement over the premise of Gesamtkunstwerk. With the banker Fritz Wärndorfer and the artist Koloman Moser he established the Wiener Werkstätte, which was to last until 1932. He designed many products for the Wiener Werkstätte of which designer chairs, most notably "Sitzmaschine" Chair, a lamp, and sets of glasses have reached the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, and a tea service has reached the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hoffmann's style eventually became more sober and abstract and it was limited increasingly to functional structures and domestic products. In 1906, Hoffmann built his first great work on the outskirts of Vienna, the Sanatorium Purkersdorf . Compared to the Moser House, with its rusticated vernacular roof, this was a great advancement towards abstraction and a move away from traditional Arts and Crafts and historicism. This project served as a major precedent and inspiration for the modern architecture that would develop in the first half of the 20th century, for instance the early work of Le Corbusier. It had a clarity, simplicity, and logic that foretold of a Neue Sachlichkeit.

Through contacts with Adolphe Stoclet, who sat on the supervisory board of the Austro-Belgischen Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft, he was commissioned to build the Palais Stoclet in Brussels from 1905 to 1911 for this wealthy banker and railway financier. This masterpiece of Jugendstil, was an example of Gesamtkunstwerk, replete with murals in the dining room by Klimt and four copper figures on the tower by Franz Metzner. In 1907, Hoffmann was co-founder of the Deutscher Werkbund, and in 1912 of the Österreichischer Werkbund. After World War II, he took on official tasks, that of an Austrian general commissioner with the Venice Biennale and a membership in the art senate.

Some of Hoffmann's domestic designs can still be found in production today, such as the Rundes Modell cutlery set that is manufactured by Alessi. Originally produced in silver the range is now produced in high quality stainless steel. Another example of Hoffmann’s strict geometrical lines and the quadratic theme is the iconic Kubus Armchair. Designed in 1910, Kubus Armchair was presented at the International Exhibition held in Buenos Aires on the centennial of Argentinean Independence known as May Revolution. His constant use of squares and cubes earned him the nickname "Quadratl-Hoffmann" (little square Hoffmann).

Although he said little to his students, Hoffmann was a highly esteemed and admired teacher. He tried to bring out the best in each member of his class by means of challenging assignments, which were occasionally work on real commissions. Where he detected talent among young artists he was willing or eager to promote it; Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele and Le Corbusier were the most prominent beneficiaries of his benevolence towards a promising next generation. Le Corbusier was offered a job in his office, Schiele was helped financially and Kokoschka was given work in the Wiener Werkstätte. As a member of the international jury for the competition to design a palace for the League of Nations at Geneva in 1927, he belonged to the minority who voted for Le Corbusier’s project, and the latter always spoke with admiration of his Viennese colleague.

The critical reception of Hoffmann’s oeuvre has faithfully mirrored the changing tastes and ideologies in the history of 20th century architecture. He received favourable attention from the critics early in his career; in 1901 The Studio brought him to the attention of the English speaking world through an illustrated article written by Fernand Khnopff. He was also given extensive coverage in the special volume The Art Revival in Austria that was published by The Studio in 1906. In France, Art et décoration published favourable reviews of his early and his mature work. Naturally his most extensive and detailed reviews are found in German language periodicals, in particular Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration where many well illustrated articles were devoted to his designs. His international exhibition work also helped to make his name widely known, and many distinguished contributors to the Festschrift on his 60th birthday acclaimed him as a master. Honours bestowed on him included the cross of a commander of the Légion d’honneur and the Honorary Fellowship of the American Institute of Architects. The critic Henry - Russell Hitchcock in 1929 wrote, ‘In Germany as well as in Austria, Hoffmann’s manner has profoundly influenced the New Tradition’. Only three years later, however, when together with Philip Johnson he published The International Style, Hitchcock no longer even mentioned Hoffmann’s name. Siegfried Giedion in his influential Space, Time and Architecture did not do justice to Hoffmann’s oeuvre because it would not fit easily into his polemically simplified version of architectural history. Despite honours and praise on the occasions of Hoffmann’s 80th and 85th birthdays, he was virtually forgotten by the time of his death. Although his true stature and contribution were acknowledged by such masters as Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Gio Ponti and Carlo Scarpa, the younger generation of architects and historians ignored him.

The

process of rediscovery and reappraisal began in 1956 with a small book

by Giulia Veronesi and during the 1970s gained momentum with a number

of exhibitions and smaller publications. In the 1980s several

monographs were published and major exhibitions held. Imitations of his

style also began to occur, and replicas of his furniture, fabrics, and

of some objects he had designed became commercial successes, while

original pieces and drawings from his hand fetched record prices in the

auction rooms.