<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Victor Yakovlevich Bunyakovsky, 1804

- Sculptor Victor Rousseau, 1865

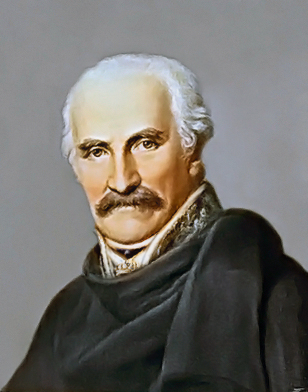

- Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt, 1742

PAGE SPONSOR

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt (December 16, 1742 – September 12, 1819), Graf (Count), later elevated to Fürst (Prince) von Wahlstatt, was a Prussian Generalfeldmarschall (field marshal) who led his army against Napoleon I at the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig in 1813 and at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 with the Duke of Wellington. He is honoured with a bust in the German Walhalla temple near Regensburg.

The honorary citizen of Berlin, Hamburg and Rostock bore the nickname "Marschall

Vorwärts" ("Marshal Forward") because of his approach to warfare. There was a German idiom,

"ran wie Blücher" ("on it like Blücher"), meaning that

someone is taking very direct and aggressive action, in war or

otherwise. Gebhard

Leberecht

von Blücher was born in Rostock, Mecklenburg,

a

Baltic port in northern Germany. His family had been landowners in

northern Germany since at least the 13th century. He

began

his military career at sixteen, when he joined the Swedish Army as a Hussar.

At the time Sweden was at war with Prussia in the Seven Years' War.

Blücher

took part in the Pomeranian campaign

of 1760, where he was captured in a skirmish with Prussian Hussars. The

colonel of the Prussian regiment, Belling, was impressed with the young

hussar and had him join his regiment. He

took

part in the later battles of the Seven Years' War, and as a hussar officer

gained much experience of light cavalry work. In peace, however, his

ardent spirit led him into excesses of all kinds, such as mock execution of a priest suspected of

supporting Polish

uprisings in 1772. Due to this, he was passed over for promotion

to Major.

Blücher sent in a rude letter of resignation, which Frederick the

Great granted in 1773: Der

Rittmeister

von Blücher kann sich zum Teufel scheren (Cavalry Captain von

Blücher can go to the devil). He

then

settled

down to farming, and in fifteen years he had acquired an

honorable independence, a wife, 7 children, and membership in the Freemasons.

During

the lifetime of Frederick the

Great,

Blücher was unable to return to the army, but after the king's

death in 1786, he was reinstated as a major in his old regiment, the Red Hussars in 1787. Blücher took part in the expedition

to the Netherlands in 1787, and the following year was

promoted to lieutenant colonel. In 1789 he received Prussia's highest military

order, the Pour le

Mérite,

and in 1794 he became colonel of the Red Hussars. In 1793 and 1794 he

distinguished himself in cavalry actions against the French, and for

his success at Kirrweiler was promoted to major general. In 1801 he

was promoted to lieutenant general. He

was

one

of the leaders of the war party in Prussia in 1805 – 1806, and

served as a cavalry general in the disastrous campaign of the latter

year. At Auerstedt Blücher

repeatedly charged at the head of the Prussian cavalry, but too early

and without success. In the retreat of the broken armies he commanded

the rearguard of Prince Hohenlohe's

corps,

and upon the capitulation of

the main body at Prenzlau, he led a remnant of the Prussian army away

to the north, after having secured 34 cannon in cooperation with Scharnhorst.

In

the neighborhood of Lübeck he fought a series of

combats, which, however, ended in his being forced to surrender at Ratekau (November

7, 1806). Blücher insisted that a clause be written in the

capitulation document that he had to surrender due to lack of

provisions and ammunition, and that his soldiers be honoured by a

French formation along the street. He was allowed to keep his sabre and

to move freely, only bound by his word of honour, and soon was

exchanged for Marshal Claude

Victor-Perrin, duc de Belluno, and was actively employed in

Pomerania, at Berlin and at Königsberg until the conclusion of the

war. After

the

war,

Blücher was looked upon as the natural leader of the

Patriot Party, with which he was in close touch during the period of

Napoleonic domination. But his hopes of an alliance with Austria in

the war of 1809 were disappointed. In this year he was made general of

cavalry. In 1812 he expressed himself so openly on the alliance of Russia with France that he was recalled from

his military governorship of Pomerania and virtually banished from the court. Following the start of the 1813

War

of Liberation,

Blücher was again placed in high command, and he was present at Lützen and Bautzen. During the armistice, he worked on the organization of the

Prussian forces, and when the war was resumed, became

commander-in-chief of the Army

of

Silesia, with August

von

Gneisenau and Muffling as his principal staff officers and

40,000 Prussians and 50,000 Russians under his command. The

irresolution

and

divergence of interests usual in allied armies found

in him a restless opponent. Knowing that if he could not induce others

to co-operate he was prepared to attempt the task at hand by himself

often caused other generals to follow his lead. He defeated Marshal

Macdonald at the Katzbach,

and

by his victory over Marshal Marmont at Möckern led the way to the decisive

defeat of Napoleon at Leipzig.

This was the fourth battle between Napoleon and Blucher and the first

that Blucher won. Leipzig was taken by Blücher's own army on the

evening of the last day of the battle. On

the day of Möckern (October 16, 1813) Blücher was made a

field marshal, and after the victory he pursued the French with his

accustomed energy. In the winter of 1813 – 1814 Blücher, with his

chief staff officers, was mainly instrumental in inducing the allied

sovereigns to carry the war into France itself. The combat of

Brienne and the Battle of La

Rothière were

the chief incidents of the first stage of the celebrated campaign of

1814, and they were quickly followed by victories of Napoleon over

Blücher at Champaubert, Vauchamps and Montmirail.

But

the courage of the Prussian leader was undiminished, and his great

victory at Laon (March 9 to 10) practically

decided the fate of the campaign. After

this,

Blücher infused some of his energy into the operations of Prince

Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia, and at last this army and the

Army of Silesia marched in one body directly towards Paris. The victory of

Montmartre, the entry of the allies into the French capital, and

the overthrow of the First Empire were the direct

consequences. Blücher

was inclined to punish the city of Paris severely for the sufferings of

Prussia at the hands of the French armies, but the allied commanders

intervened. Blowing up the Jena Bridge near the Champ de Mars was said to be one of his

contemplated acts. On June 3, 1814, he was made Prince of Wahlstatt (in Silesia on the Katzbach

battlefield), and soon

afterwards he paid

a

visit to England, where he

was received enthusiastically everywhere he went. After

the

war he retired to Silesia, but the return of Napoleon from Elba soon called him back to

service. He was put in command of the Army of the Lower Rhine, with

General August von

Gneisenau as his

chief of staff. In the campaign of 1815, the Prussians sustained a

serious defeat at the outset at Ligny

(June

16), in the course of which the old field marshal was repeatedly ridden

over by cavalry and lay trapped under his dead horse for several hours,

his life saved only by the devotion of his aide-de-camp,

Count Nostitz.

He

was

unable to resume command for some hours, and Gneisenau drew off

the defeated army and rallied it. After bathing his wounds in brandy,

and fortified by liberal internal application of the same, Blücher

rejoined his army. Gneisenau feared that the British had reneged on

their earlier agreements and favored a withdrawal, but Blücher

convinced him to send two Corps to join Wellington at Waterloo. He

then led his army on a nearly endless, tortuous march along muddy

paths, arriving on the field of Waterloo in the late afternoon. With

the battle hanging in the balance Blücher's army intervened with

decisive and crushing effect, his vanguard drawing off Napoleon's badly

needed reserves, and his main body being instrumental in crushing

French resistance. This victory led the way to a decisive victory

through the relentless pursuit of the French by the Prussians. The

allies re-entered Paris on July 7. Prince Blücher remained in the

French capital for a few months, but his age and infirmities compelled

him to retire to his Silesian residence at Krieblowitz (now Krobielowice in Poland), where he died in 1819, aged 76. In

1945

his grave was destroyed by Soviet troops and his corpse exhumed.

As of 2008, in Poland, von

Blücher's grave remains

in its destroyed state. Blücher

retained

to

the end of his life that wildness of character and

proneness to excesses which had caused his dismissal from the army in

his youth, but, however they may be regarded, these faults sprang

always from the ardent and vivid temperament which made him a dashing

leader of people. Whilst by no means a military genius, his sheer

determination and ability to spring back from errors made him a

competent leader. He

was twice married, and had, by his first marriage, two sons and a

daughter. Statues were erected to his memory at Berlin, Breslau, Rostock and Kaub. In

gratitude for his service, an early British locomotive engineer named a

locomotive after him, and Oxford

University granted

him

an honorary doctorate (Doctor of Laws), about which he is supposed

to have said that if he was made a doctor they should at least make Gneisenau an apothecary. Three

ships of the German navy have been named in honour of Blücher. The

first to be so named was a corvette built at Kiel's Norddeutsche Schiffbau AG (later renamed the Krupp-Germaniawerft)

and

launched 20 March 1877. Taken out of service after a boiler explosion in 1907, she

ended her days as a coal freighter in Vigo,

Spain. On

11 April 1908, the Panzerkreuzer SMS Blücher was launched from the

Imperial Shipyard in Kiel. This ship was sunk on 24 January 1915 in WWI at the Battle of

Dogger Bank. The World War II

German heavy cruiser Blücher was sunk in the invasion of Norway: both

ships to carry the name Blücher in the World Wars were sunk within eight

months of the respective war commencing.