<Back to Index>

- Explorer William Edward Parry, 1790

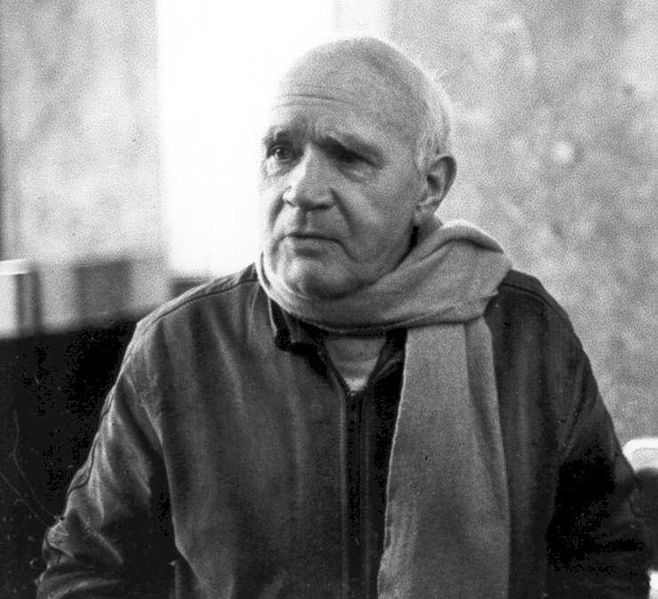

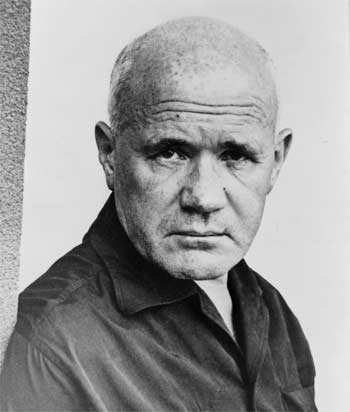

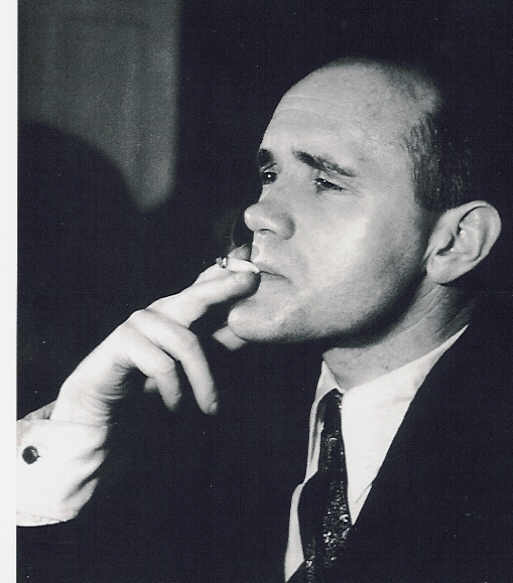

- Novelist Jean Genet, 1910

- President of the Republic of Poland (4th in Exile) Edward Bernard Raczyński, 1891

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean Genet (December 19, 1910 – April 15, 1986) was a prominent and controversial French novelist, playwright, poet, essayist, and political activist. Early in his life he was a vagabond and petty criminal, but later took to writing. His major works include the novels Querelle of Brest, The Thief's Journal, and Our Lady of the Flowers, and the plays The Balcony, The Blacks, The Maids and The Screens.

Genet's mother was a young prostitute who raised him for the first year of his life before putting him up for adoption. Thereafter Genet was raised in the provinces by a carpenter and his family, who according to Edmund White's biography, were loving and attentive. While he received excellent grades in school, his childhood involved a series of attempts at running away and incidents of petty theft (although White also suggests that Genet's later claims of a dismal, impoverished childhood were exaggerated to fit his outlaw image).

After the death of his foster mother, Genet was placed with an elderly couple but remained with them less than two years. According to the wife, "he was going out nights and also seemed to be wearing makeup." On one occasion he squandered a considerable sum of money, which they had entrusted him for delivery elsewhere, on a visit to a local fair. For this and other misdemeanors, including repeated acts of vagrancy, he was sent at the age of 15 to Mettray Penal Colony where he was detained between 2 September 1926 and 1 March 1929. In The Miracle of the Rose (1946), he gives an account of this period of detention, which ended at the age of 18 when he joined the Foreign Legion. He was eventually given a dishonorable discharge on grounds of indecency (having been caught engaged in a homosexual act) and spent a period as a vagabond, petty thief and prostitute across Europe — experiences he recounts in The Thief's Journal (1949). After returning to Paris, France in 1937, Genet was in and out of prison through a series of arrests for theft, use of false papers, vagabondage, lewd acts and other offenses. In prison, Genet wrote his first poem, "Le condamné à mort," which he had printed at his own cost, and the novel Our Lady of the Flowers (1944). In Paris, Genet sought out and introduced himself to Jean Cocteau, who was impressed by his writing. Cocteau used his contacts to get Genet's novel published, and in 1949, when Genet was threatened with a life sentence after ten convictions, Cocteau and other prominent figures, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Pablo Picasso, successfully petitioned the French President to have the sentence set aside. Genet would never return to prison.

By 1949 Genet had completed five novels, three plays and numerous poems. His explicit and often deliberately provocative portrayal of homosexuality and criminality was such that by the early 1950s his work was banned in the United States. Sartre wrote a long analysis of Genet's existential development (from vagrant to writer) entitled Saint Genet (1952) which was anonymously published as the first volume of Genet's complete works. Genet was strongly affected by Sartre's analysis and did not write for the next five years. Between 1955 and 1961 Genet wrote three more plays as well as an essay called "What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn Into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down the Toilet", on which hinged Jacques Derrida's analysis of Genet in his seminal work "Glas". During this time he became emotionally attached to Abdallah, a tightrope walker. However, following a number of accidents and Abdallah's suicide in 1964, Genet entered a period of depression, even attempting suicide.

From the late 1960s, starting with a homage to Daniel Cohn-Bendit after the events of May 1968, Genet became politically active. He participated in demonstrations drawing attention to the living conditions of immigrants in France. In 1970 the Black Panthers invited him to the USA, where he stayed for three months giving lectures, attending the trial of their leader, Huey Newton, and publishing articles in their journals. Later the same year he spent six months in Palestinian refugee camps, secretly meeting Yasser Arafat near Amman. Profoundly moved by his experiences in Jordan and the USA, Genet wrote a final lengthy memoir about his experiences, A Prisoner of Love, which would be published posthumously. Genet also supported Angela Davis and George Jackson, as well as Michel Foucault and Daniel Defert's Prison Information Group. He worked with Foucault and Sartre to protest police brutality against Algerians in Paris, a problem persisting since the Algerian War of Independence, when beaten bodies were to be found floating in the Seine. In September 1982 Genet was in Beirut when the massacres took place in the Palestinian camps of Sabra and Shatila. In response, Genet published "Quatre heures à Chatila" ("Four Hours in Shatila"), an account of his visit to Shatila after the event. In one of his rare public appearances during the later period of his life, at the invitation of Austrian philosopher Hans Köchler he read from his work during the inauguration of an exhibition on the massacre of Sabra and Shatila organized by the International Progress Organization in Vienna, Austria, on 19 December 1983.

Genet developed throat cancer and

was found dead on April 15, 1986 in a hotel room in Paris. Genet may

have fallen on the floor and fatally hit his head. He is buried in the

Spanish Cemetery in Larache, Morocco. He is remembered in the Dire

Straits song Les Boys on the album Making Movies, as well as in the song "Beautiful Boyz"

by Cocorosie. Throughout

his five early novels, Genet works to subvert the traditional set of moral values of his assumed readership.

He celebrates a beauty in evil,

emphasizes his singularity, raises violent criminals to icons,

and enjoys the specificity of gay gesture and coding and the depiction

of scenes of betrayal. Our Lady of the

Flowers (Notre

Dame des Fleurs 1943)

is

a journey through the prison underworld, featuring a fictionalized

alter ego by the name of Divine, usually referred to in the feminine,

at the center of a circle of tantes ("aunties"

or "queens") with colorful sobriquets such as Mimosa I, Mimosa II,

First Communion and the Queen of Rumania. The two auto-fictional novels, The Miracle of

the Rose (Miracle

de la rose 1946) and The Thief's

Journal (Journal

du voleur 1949),

describe Genet's time in Mettray Penal

Colony and his

experiences as a vagabond and prostitute across Europe. Querelle de

Brest (1947)

is set in the midst of the port town of Brest, where sailors and the

sea are associated with murder;

and Funeral Rites (1949)

is a story of love and betrayal across political divides, written this

time for the narrator's lover, Jean Decarnin, killed by the Germans in WWII. Prisoner of Love published

in 1986, after Genet's death, is a memoir of his encounters with

Palestinian fighters and Black Panthers; it has, therefore, a more

documentary tone than his fiction. Genet's

plays

present highly stylized depictions of ritualistic struggles

between outcasts of various kinds and their oppressors. Social

identities are parodied and shown to involve complex layering through

manipulation of the dramatic fiction and its inherent potential for

theatricality and role play; maids imitate one another and their

mistress in The Maids (1947);

or the clients of a brothel simulate roles of political power before,

in a dramatic reversal, actually becoming those figures, all surrounded

by mirrors that both reflect and conceal, in The Balcony

(1957).

Most strikingly, Genet offers a critical dramatisation of what Aimé

Césaire called negritude in The Blacks

(1959),

presenting

a violent assertion of Black identity and anti-white

virulence framed in terms of mask wearing and roles adopted and

discarded. His most overtly political play is The Screens (1964),

an epic account of the Algerian War of

Independence. He also wrote another full length drama, Splendid's,

in 1948 and a one act play,

Her (Elle),

in 1955, though neither was published or produced during Genet's

lifetime. The Blacks was, after The Balcony, the second of Genet's plays to be

staged in New York. The production was the longest running off-Broadway non-musical

of the decade. Originally premiered in Paris in 1959, this 1961 New

York production ran for 1,408 performances. The original cast featured James

Earl Jones, Roscoe

Lee Browne, Louis

Gossett, Jr., Cicely

Tyson, Godfrey

Cambridge, Maya

Angelou and Charles

Gordone. In

1950, Genet directed Un Chant d'Amour,

a 26 minute black-and-white film depicting the fantasies of a gay male prisoner and

his prison warden. Genet's

work has also been adapted for film and produced by other filmmakers.

In 1982, Rainer Werner

Fassbinder released Querelle,

his final film, which was based on Querelle de

Brest. It starred Brad Davis, Jeanne Moreau and Franco Nero.

Genet never saw the film because smoking was not allowed in movie

theatres. Tony Richardson directed a film, Mademoiselle, which

was based on a short story by Genet. It starred Jeanne Moreau with the screenplay written

by Marguerite Duras. Todd Haynes' Poison was also based on the

writings of Genet. Several of Genet's plays were adapted

into films. The Balcony (1963), directed by Joseph

Strick, starred Shelley

Winters as Madame Irma, Peter

Falk, Lee

Grant and Leonard

Nimoy. The Maids was filmed in 1974 and starred Glenda

Jackson, Susannah

York and Vivien

Merchant. Italian director Salvatore

Samperi directed another adaptation of the same

play, La Bonne (Eng. Corruption), starring Florence

Guerin and Katrine

Michelsen.