<Back to Index>

- Cartographer Oronce Finé, 1494

- Playwright John Fletcher, 1579

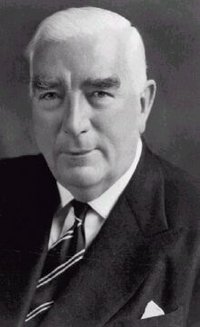

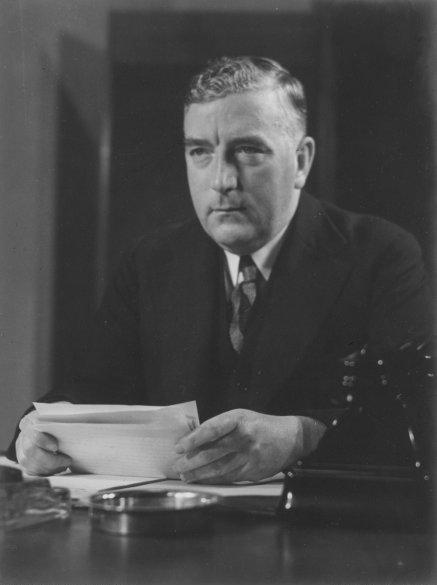

- 12th Prime Minister of Australia Robert Gordon Menzies, 1894

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, KT, AK, CH, FAA, FRS, QC (20 December 1894 – 15 May 1978), Australian politician, was the 12th and longest serving Prime Minister of Australia. His first term as Prime Minister commenced in 1939, after the death in office of the United Australia Party leader Joseph Lyons and a short term interim premiership by Sir Earle Page. His party narrowly won the 1940 election, which produced the first hung parliament in Australian history, with the support of independent MPs in the House. A year later, his government was brought down by those same MPs crossing the floor. He spent eight years in opposition, during which he founded the Liberal Party of Australia. He again became Prime Minister at the 1949 election, and he then dominated Australian politics until his retirement in 1966.

Menzies

was renowned as a brilliant speaker, both on the floor of Parliament

and on the hustings;

his speech "The Forgotten

People" is an example of his oratorical skills. Throughout

his life and career, Menzies held strong beliefs in the Monarchy and in traditional ties

with Britain. In 1963 Menzies was invested as the first and only

Australian Knight of the Order of the

Thistle. Menzies is regarded highly in Prime

Ministerial opinion polls and

is very highly regarded in Australian society for his tenures as Prime

Minister. Robert

Gordon Menzies was born to James Menzies and Kate Menzies (née

Sampson) in

Jeparit, a town in the Wimmera region of western Victoria,

on 20 December 1894. His father James was a storekeeper, the son of Scottish crofters who had immigrated to

Australia in the mid 1850s in the wake of the Victorian gold

rush. His maternal grandfather, John Sampson, was a Cornish miner from Penzance who also came to seek his

fortune on the gold fields, in Ballarat. His

father and one of his uncles had been members of the Victorian

Parliament, while another uncle had represented Wimmera in the House of

Representatives. He was proud of his Highland ancestry – his

enduring nickname, Ming,

came from /ˈmɪŋəs/,

the Scots — and his own preferred —

pronunciation of Menzies.

His middle name, Gordon, was given to him in honour and memory of Charles George

Gordon, a British army officer killed in Khartoum in 1885. Menzies

was first educated at a one room school, then later at private schools

in Ballarat and Melbourne (Wesley College),

and studied law at the University of

Melbourne graduating

in 1916. When World War I began,

Menzies was 19 years old and held a commission in the university's

militia unit. Menzies resigned his commission at the very time others

of his age and class clamoured to be allowed to enlist. It was later

stated that, since the family had made enough of a sacrifice to the war

with the enlistment of two of three eligible brothers, Menzies should

stay to finish his studies. Menzies

himself

never explained the reason why he chose not to enlist.

Subsequently he was prominent in undergraduate activities and won

academic prizes and declared himself to be a patriotic supporter of the

war and conscription. Menzies

was admitted to the Victorian Bar and to the High Court of Australia in

1918 and soon became one of Melbourne's leading lawyers after

establishing his own practice. In 1920 he married Pattie Leckie,

the daughter of federal Nationalist,

and later Liberal, MP, John Leckie. In 1928,

Menzies gave up his law practice to enter state parliament as a member

of the

Victorian Legislative Council from East Yarra

Province, representing the Nationalist

Party of Australia.

His candidacy was nearly defeated when a group of ex-servicemen

attacked him in the press for not having enlisted, but he survived this

crisis. The following year he shifted to the Legislative

Assembly as the

member for Nunawading.

Before the election, he founded the Young Nationalists as his party's

youth wing and served as its first president. He was Deputy Premier

of Victoria from May

1932 until July 1934. Menzies

transferred to federal politics in 1934, representing the United

Australia Party (UAP

-- the

Nationalists had merged with other non-Labor groups to form the UAP

during his tenure as a state parliamentarian) in the upper class

Melbourne electorate of Kooyong.

He was immediately appointed Attorney General and Minister for Industry

in the Lyons government. In 1937 he was appointed a Privy Councillor.

In late 1934 and early 1935 Menzies unsuccessfully prosecuted the Lyons

government's case for the attempted

exclusion from

Australia of

Egon Kisch,

a Czech Jewish communist. Because of this, some accused Menzies of

being pro-Nazi, whilst others saw it as an early example of his strong

opposition to communism. Following the outbreak of World War II Menzies found it necessary

to distance himself from the controversy by claiming Interior Minister Thomas Paterson was responsible since he

made the initial order to exclude Kisch. Animosity

developed between Page and Menzies which was aggravated when Page

became Acting Prime Minister during Lyons' illness after October 1938.

Menzies and Page attacked each other publicly. He later became deputy

leader of the UAP. His supporters said he was Lyons's natural

successor; his critics accused Menzies of wanting to push Lyons out, a

charge he denied. In 1938 his enemies ridiculed him as "Pig Iron Bob",

the result of his industrial battle with waterside workers who refused

to load scrap iron being sold to Imperial Japan.

In

1939, however, he resigned from the Cabinet in protest at

postponement of the national insurance scheme. With Lyons' sudden death

on 7 April 1939, Page became acting Prime Minister until the UAP could

elect a leader. On

18 April, Menzies was elected Leader of the UAP and was sworn in as

Prime Minister eight days later. A crisis arose almost immediately,

however, when Page refused to serve under him. In an extraordinary

personal attack in the House, Page accused Menzies of cowardice for not

having enlisted in the War, and of treachery to Lyons. Menzies then

formed a minority

government. When Page was deposed as Country Party leader a few

months later, Menzies reformed the Coalition with Page's successor, Archie Cameron. - Menzies

radio broadcast to the nation on 3 September 1939 informing Australia

that the country was at war with Germany and her allies. In

September 1939, Menzies found himself a wartime leader of a small

nation of 7 million people that depended on Britain for defence against

the looming threat of the Japanese Empire, with 100 million people, a

very powerful military, and an aggressive foreign policy that looked

south. He did his best to rally the country, but the bitter memories of

the disillusionment which followed the First World War made this

difficult. Added to this was the fact that Menzies had not served in

that war, and that as Attorney General and Deputy Prime Minister,

Menzies had made an official visit to Germany in 1938, and like his

Opposition at the time, supported Neville

Chamberlain's policy of Appeasement.

At

the 1940 election, the UAP was nearly defeated, and Menzies'

government survived only thanks to the support of two independent MPs, Arthur Coles and Alex Wilson.

The Australian

Labor Party (ALP),

under John Curtin,

refused

Menzies' offer to form a war coalition, and also opposed using

the Australian army for a European war, preferring to keep it at home

to defend Australia. The ALP did agree to participate in the Advisory War

Council, however. Menzies sent the bulk of the army to help the

British in the Middle East and Singapore, and told Winston

Churchill the

Royal Navy should strengthen its Far Eastern forces. In

1941 Menzies spent months in Britain discussing war strategy with

Churchill and other leaders, while his position at home deteriorated.

The Australian historian David Day has

suggested that Menzies hoped to replace Churchill as British Prime

Minister, and that he had some support in Britain for this. Other

Australian writers, such as Gerard Henderson,

have

rejected this theory. When Menzies came home, he found he had lost all

support, and was forced to resign as Prime Minister. However, the

UAP was so bereft of leadership that it was forced to allow the Country

Party leader, Arthur Fadden,

to

become Prime Minister even though the Country Party was the junior

partner in the Coalition. Menzies was very bitter about what he saw as

this betrayal by his colleagues, and almost left politics. However, he

was prevailed upon to remain UAP leader and Minister for

Defence Co-ordination in

Fadden's government. Extract; The Forgotten

People, Robert Menzies, 22 May 1942; Fadden's

government was defeated in Parliament later in 1941, and Labor formed a

government under John Curtin. Menzies argued that he should become Leader of the

Opposition, but most of his colleagues favoured Fadden. Menzies

resigned the leadership in disgust and was succeeded by Billy Hughes.

However, Menzies remained an opposition frontbencher under Fadden. In

1943 Curtin won a huge election victory. Hughes resigned as UAP leader,

and Menzies returned to the leadership. Fadden yielded the post of

Opposition Leader back to Menzies as well. During 1944 Menzies held a

series of meetings at 'Ravenscraig' an old homestead in Aspley to

discuss forming a new anti-Labor party to replace the moribund UAP.

This was the Liberal Party, which was launched in early 1945 with

Menzies as leader. But Labor was firmly entrenched in power and in 1946

Curtin's successor, Ben Chifley,

was comfortably re-elected. Comments that "we can't win with Menzies"

began to circulate in the conservative press. Over the

next few years, however, the anti-communist atmosphere of the early Cold War began

to erode Labor's support. In 1947, Chifley announced that he intended

to nationalise Australia's private banks, arousing intense middle class

opposition which Menzies successfully exploited. The 1949 coal strike,

engineered by the Communist Party,

also played into Menzies' hands. In the December 1949

election,

Menzies won power for the second time in a massive landslide, scoring a

48-seat swing — still the largest defeat of a sitting government at the

federal level in Australia. In 1950 Menzies was awarded the Legion of Merit (Chief Commander) by U.S.

President Harry S. Truman for "exceptionally

meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services 1941 –

1944 and December 1949 – July 1950". Although

Menzies had a comfortable majority in the House, the ALP controlled

Senate made life very difficult for him. In 1951 Menzies introduced

legislation to ban the Communist Party, hoping that the Senate would

reject it and give him an excuse for a double

dissolution election,

but Labor let the bill pass. It was subsequently ruled

unconstitutional by

the High Court.

But when the Senate rejected his banking bill, he called a double

dissolution and at

the election won control of both Houses. Later in

1951 Menzies decided to hold a referendum on

the question of changing the Constitution to permit the parliament to

make laws in respect of Communists and Communism where he said this was

necessary for the security of the Commonwealth. If passed, this would

have given a government the power to introduce a bill proposing to ban

the Communist Party (although whether it would have passed the Senate

is an open question). The new Labor leader, Dr H.V. Evatt,

campaigned

against the referendum on civil liberties grounds, and it

was narrowly defeated. This was one of Menzies' few electoral

miscalculations. He sent Australian troops to the Korean War and maintained a close

alliance with the United States. Economic

conditions, however, deteriorated, and Evatt was confident of winning

the 1954 elections. Shortly before the elections, Menzies announced

that a Soviet diplomat in Australia Vladimir Petrov,

had

defected, and that there was evidence of a Soviet spy ring in

Australia, including members of Evatt's staff. Evatt felt compelled to

state on the floor of Parliament that he'd personally written Soviet

Foreign Minister Vyacheslav

Molotov, who assured him there were no Soviet spy rings in

Australia. This Cold War scare enabled Menzies to

win the election; although Labor won a majority of the two party

preferred vote,

it came up eight seats short of toppling the Coalition. Evatt accused

Menzies of arranging Petrov's defection, but this has since been

disproved: he had simply taken advantage of it. The

aftermath of the 1954 election caused a split in the Labor Party, with

several anti-Communist members from Victoria defecting to form the Australian

Labor Party (Anti-Communist).

The new party directed its preferences to the Liberals, and Menzies was

comfortably re-elected over Evatt in 1955. Menzies was reelected almost

as easily in 1958, again with the help of preferences from what had

become the Democratic

Labor Party. By this time the post-war economic recovery was in

full swing, fuelled

by massive immigration and the growth in housing and manufacturing that

this produced. Prices for Australia's agricultural exports were also

high, ensuring rising incomes. Labor's

new leader, Arthur Calwell,

gave

Menzies a scare after an ill-judged squeeze on credit – an

effort to restrain inflation – caused a rise in unemployment. At

the 1961 election Menzies

was returned with a majority of only two seats. But Menzies was able to

exploit Labor's divisions over the Cold War and the American alliance,

and win an increased majority in the 1963 election. An

incident in which Calwell was photographed standing outside a South

Canberra hotel while the ALP Federal

Executive (dubbed

by

Menzies the "36 faceless men") was determining policy also

contributed to the 1963 victory. This was the first "television

election," and Menzies, although nearly 70, proved a master of the new

medium. Menzies' policy speech was televised on 12 November 1963, a

method that "had never before been used in Australia". The effect of this form of

political communication was studied by Colin Hughes and John Western,

who published their findings in 1966. This was itself the first such

detailed study in Australia. In 1963,

Menzies was appointed a Knight of the Order of the

Thistle (KT),[9] the

order being chosen in recognition of his Scottish heritage. He is the

only Australian ever appointed to this order, although three British governors-general

of Australia (Lord Hopetoun; Sir Ronald

Munro Ferguson, later Lord Novar; and Prince Henry,

Duke of Gloucester)

were members. He was the second of only two Australian prime ministers

to be knighted during their term of office (the first prime minister Edmund Barton was knighted during his

term in 1902). In 1965,

Menzies committed Australian troops to the Vietnam War,

and also to reintroduce conscription.

These moves were initially popular, but later became a problem for his

successors. Despite

his pragmatic acceptance of the new power balance in the Pacific after

World War II and his strong support for the American alliance, he

publicly professed continued admiration for links with Britain,

exemplified by his admiration for Queen Elizabeth

II,

and famously described himself as "British to the bootstraps". Over the

decade, Australia's ardour for Britain and the monarchy faded somewhat,

but Menzies's had not. At a function attended by the Queen at

Parliament House, Canberra, in 1963, Menzies quoted the Elizabethan poet Thomas Ford, "I did but see her

passing by, and yet I love her till I die". Menzies

retired on Australia Day 1966,

ending 38 years as an elected official. To date, he is the last

Australian Prime Minister to leave office on his own terms. He was

succeeded as Liberal Party leader and Prime Minister by his former

Treasurer, Harold Holt.

Although the coalition remained in power for almost another seven years

(until the 1972 Federal

election), it did so under four different Prime Ministers. On

his retirement he became the thirteenth Chancellor of his old

University of Melbourne, and remained the head of the University from

March 1967 until March 1972. Much earlier in 1942, he had received the

first honorary degree of Doctor of Laws of Melbourne University. His

responsibility for the revival and growth of university life in

Australia was widely acknowledged by the award of honorary degrees in

the Universities of Queensland, Adelaide, Tasmania, New South Wales,

and the Australian National University and by thirteen universities in

Canada, the U.S.A. and Britain, including Oxford and Cambridge. Many

learned institutions, including the Royal College

of Surgeons (Hon.

FRCS) and the Royal

Australasian College of Physicians (Hon. FRACP), elected him

to Honorary Fellowships, and the Australian

Academy of Science, for which he supported its establishment in

1954, made him a fellow (FAAS) in 1958. In July

1966 the Queen appointed Menzies to the ancient office of Lord Warden of

the Cinque Ports and

Constable of Dover Castle,

taking official residence at Walmer Castle during

his annual visits to Britain. He toured the United States giving

lectures, and he published two volumes of memoirs. At the end of 1966

Menzies took up a scholar-in-residence position at the University of

Virginia.

Menzies encountered some public tribulation in retirement; however,

when he suffered strokes in 1968 and 1971, he faded from public view. Menzies

died from a heart attack in Melbourne in 1978 and

was accorded a state funeral, held in Scots' Church,

Melbourne, at which Prince Charles represented Queen Elizabeth

II. Menzies

was Prime Minister for a total of 18 years, five months, and 12 days,

by far the longest term of any Australian Prime Minister, and during

his second term he dominated Australian politics as no one else has

ever done. He managed to live down the failures of his first term in

office, and to rebuild the conservative side of politics from the nadir

it hit in 1943. Menzies also did much to develop higher education in

Australia, and he also made the increasing development of Canberra one of his big projects.

However, it can also be noted that while retaining government on each

occasion, Menzies lost the two-party-preferred

vote in 1940, 1954, and 1961. He

was the only Australian Prime Minister to recommend the appointment of

four governors general (Sir William Slim, and Lords Dunrossil, De

L'Isle, and Casey). Only two other Prime Ministers have ever chosen

more than one governor general. (Malcolm Fraser chose Sir Zelman Cowen

and Sir Ninian Stephen; and John Howard chose Peter Hollingworth and

Michael Jeffery.) Critics

say that Menzies's success was mainly due to the good luck of the long

post-war boom and his manipulation of the anti-communist fears of the

Cold War years, both of which he exploited with great skill. He was

also crucially aided by the crippling dissent within the Labor Party in

the 1950s and especially by the ALP split of

1954. Several

books have been filled with anecdotes about him and with his many witty

remarks. While he was speaking in Williamstown,

Victoria, in 1954, a heckler shouted, "I wouldn’t vote for you

if you were the Archangel

Gabriel" – to which Menzies coolly replied "If I were the

Archangel Gabriel, I’m afraid you wouldn't be in my constituency." Planning

for an official biography of Menzies began soon after his death, but it

was long delayed by Dame Pattie Menzies' protection of her husband's

reputation and her refusal to co-operate with the appointed biographer, Frances McNicoll.

In 1991, the Menzies family appointed Professor A.W. Martin to write a biography, which

appeared in two volumes, in 1993 and 1999.

“

"Fellow

Australians, It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in

consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of

Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a

result, Australia is also at war."

”

“

"I

do not believe that the real life of this nation is to be found either

in great luxury hotels and the petty gossip of so-called fashionable

suburbs, or in the officialdom of the organised masses. It is to be

found in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and

who, whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in

their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their

race. The home is the foundation of sanity and sobriety; it is the

indispensable condition of continuity; its health determines the health

of society as a whole."

”