<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Johann Friedrich Pfaff, 1765

- Composer Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini, 1858

- Secretary of State Frank Billings Kellogg, 1856

PAGE SPONSOR

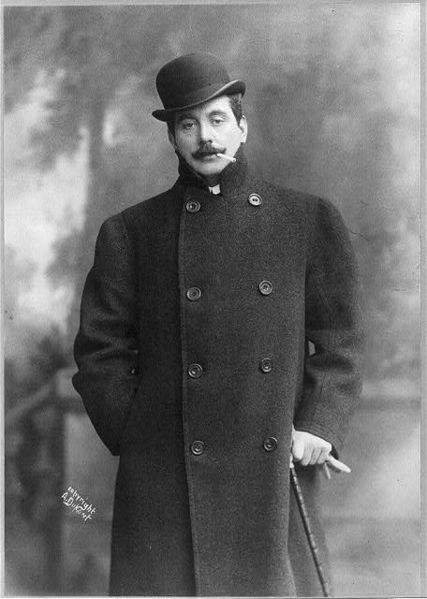

Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini (22 December 1858 – 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer whose operas, including La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, and Turandot, are among the most frequently performed in the standard repertoire. Some of his arias, such as "O mio babbino caro" from Gianni Schicchi, "Che gelida manina" from La bohème, and "Nessun dorma" from Turandot, have become part of popular culture.

Puccini was born in Lucca in Tuscany, into a family with five generations of musical history behind them, including composer Domenico Puccini. His father died when Giacomo was five years old, and he was sent to study with his uncle Fortunato Magi, who considered him to be a poor and undisciplined student. Magi may have been prejudiced against his nephew because his contract as choir master stipulated that he would hand over the position to Puccini "as soon as the said Signore Giacomo be old enough to discharge such duties." Puccini took the position of church organist and choir master in Lucca, but it was not until he saw a performance of Verdi's Aida that he became inspired to be an opera composer. He and his brother, Michele, walked 18.5 mi (30 km) to see the performance in Pisa.

In 1880, with the help of a relative and a grant, Puccini enrolled in the Milan Conservatory to study composition with Stefano Ronchetti - Monteviti, Amilcare Ponchielli, and Antonio Bazzini. In the same year, at the age of 21, he composed the Messa, which marks the culmination of his family's long association with church music in his native Lucca. Although Puccini himself correctly titled the work a Messa, referring to a setting of the Ordinary of the Catholic Mass, today the work is popularly known as his Messa di Gloria, a name that technically refers to a setting of only the first two prayers of the Ordinary, the Kyrie and the Gloria, while omitting the Credo, the Sanctus, and the Agnus Dei. The work anticipates Puccini's career as an operatic composer by offering glimpses of the dramatic power that he would soon bring forth onto the stage; the powerful "arias" for tenor and bass soloists are certainly more operatic than is usual in church music and, in its orchestration and dramatic power, the Messa compares interestingly with Verdi's Requiem.

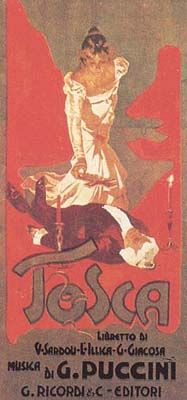

While studying at the Conservatory, Puccini obtained a libretto from Ferdinando Fontana and entered a competition for a one act opera in 1882. Although he did not win, Le Villi was later staged in 1884 at the Teatro Dal Verme and it caught the attention of Giulio Ricordi, head of G. Ricordi & Co. music publishers, who commissioned a second opera, Edgar, in 1889. Edgar failed: it was a bad story and Fontana's libretto was poor. This may have had an effect on Puccini's thinking because when he began his next opera Manon Lescaut he announced that he would write his own libretto so that "no fool of a librettist" could spoil it for him. Ricordi persuaded him to accept Leoncavallo as his librettist, but Puccini soon asked Ricordi to remove him from the project. Four other librettists were then involved with the opera, due mainly to Puccini constantly changing his mind about the structure of the piece. It was almost by accident that the final two, Illica and Giacosa, came together to complete the opera and they remained with Puccini for his next three operas and probably his greatest successes La Boheme, Tosca and Madama Butterfly.

It may well have been the failure of Edgar that made Puccini so apt to change his mind. Edgar nearly

cost him his career: Puccini had eloped with the married Elvira

Gemignani and Ricordi's associates were willing to turn a blind eye to

his life style as long as he was successful. When Edgar failed,

they suggested to Ricordi that he should drop Puccini, but Ricordi said

that he would stay with him and made him an allowance from his own

pocket until his next opera. Manon Lescaut was a great success and Puccini went on to become the leading operatic composer of his day. From 1891 onwards, Puccini spent most of his time at Torre del Lago, a small community about fifteen miles from Lucca situated between the Ligurian Sea and Lake Massaciuccoli, just south of Viareggio.

While renting a house there, he spent time hunting but regularly

visited Lucca. By 1900 he had acquired land and built a villa on the

lake, now known as the "Villa Museo Puccini." He lived there until 1921

when pollution produced by peat works on the lake forced him to move to

Viareggio, a few kilometres north. After his death, a mausoleum was created in the Villa Puccini and the composer is buried there in the chapel, along with his wife and son who died later. The "Villa Museo Puccini" is presently owned by his granddaughter, Simonetta Puccini, and is open to the public. After

1904, compositions were less frequent. Following his passion for

driving fast cars, Puccini was nearly killed in a major accident in

1903. In 1906 Giacosa died and, in 1909, there was a scandal after

Puccini's wife, Elvira, falsely accused their maid Doria Manfredi of

having an affair with Puccini. The maid then committed suicide.

Elvira was successfully sued by the Manfredis, and Giacomo had to pay

damages. Finally, in 1912, the death of Giulio Ricordi, Puccini's

editor and publisher, ended a productive period of his career. However, Puccini completed La fanciulla del West in 1910 and finished the score of La rondine in 1916. In 1918, Il trittico premiered in New York. This work is composed of three one act operas: a horrific episode (Il tabarro), in the style of the Parisian Grand Guignol, a sentimental tragedy (Suor Angelica), and a comedy (Gianni Schicchi). Of the three, Gianni Schicchi has remained the most popular, containing the popular aria "O mio babbino caro". A

habitual Toscano cigar and cigarette chain smoker, Puccini began to

complain of chronic sore throats towards the end of 1923. A diagnosis of throat cancer led his doctors to recommend a new and experimental radiation therapy treatment, which was being offered in Brussels. Puccini and his wife never knew how serious the cancer was, as the news was only revealed to his son. Puccini died there on 29 November 1924, from complications after the treatment; uncontrolled bleeding led to a heart attack the day after surgery. News of his death reached Rome during a performance of La bohème. The opera was immediately stopped, and the orchestra played Chopin's Funeral March for the stunned audience. He was buried in Milan,

in Toscanini's family tomb, but that was always intended as a temporary

measure. In 1926 his son arranged for the transfer of his father's

remains to a specially created chapel inside the Puccini villa at Torre

del Lago. Turandot, his final opera, was left unfinished, and the last two scenes were completed by Franco Alfano based

on the composer's sketches. Some dispute whether Alfano followed the

sketches or not, since the sketches were said to be indecipherable, but

he is believed to have done so, since, together with the autographs, he

was given (still existing) transcriptions from Guido Zuccoli who was

accustomed to interpreting Puccini's handiwork. When Arturo Toscanini conducted the premiere performance in April 1926 (in front of a sold out crowd, with every prominent Italian except for Benito Mussolini in

attendance), he chose not to perform Alfano's portion of the score. The

performance reached the point where Puccini had completed the score, at

which time Toscanini stopped the orchestra. The conductor turned to the

audience and said: "Here the opera finishes, because at this point the

Maestro died." (Some record that he said, more poetically, "Here the

Maestro laid down his pen.") (Some record that then Toscanini picked up

the baton, turned to the audience, and announced, "But his disciples

finished his work." At which time the opera closed to thunderous

applause.) Toscanini's

laying down the baton has been misinterpreted by some journalists as a

gesture of disapproval of Alfano's contribution. Recently, one told his

readers with great authority that "Toscanini never conducted Turandot

again." In fact, he conducted it again on the two following nights - including Alfano's ending - a total of three performances. Toscanini

edited Alfano's suggested completion ('Alfano I'), to produce a version

now known as 'Alfano II', and this is the version usually used in

performance. However, some musicians consider Alfano I to be a more dramatically complete version. In 2002, an official new ending was composed by Luciano Berio from original sketches, but this finale has, to date, been performed only infrequently. Unlike Verdi and Wagner, Puccini did not appear to be active in the politics of his day. However, Mussolini, Fascist dictator of Italy at the time, claimed that Puccini applied for admission to the National Fascist Party.

While it has been proven that Puccini was indeed among the early

supporters of the Fascist party at the time of the election campaign of

1919 (in which the Fascist candidates were utterly defeated, earning a

meagre 4,000 votes), there appear to be no records or proof of any

application given to the party by Puccini. In addition, it can be noted

that had Puccini done so, his close friend Toscanini (an extreme

anti Fascist) would probably have severed all friendly connection with

him and ceased conducting his operas. This

notwithstanding, Fascist propaganda appropriated Puccini's figure, and

one of the most widely played marches during Fascist street parades and

public ceremonies was the "Inno a Roma" (Hymn to Rome), composed in 1919 by Puccini to lyrics by Fausto Salvatori, based on these verses from Horace's Carmen saeculare: Alme Sol, curru nitido diem qui / Promis et celas alius que et idem / Nasceris, possis nihil urbe Roma / Visere maius. (O

Sun, that unchanged, yet ever new, / Lead'st out the day and bring'st

it home, / May nothing be present to thy view / Greater than Rome!) The subject of Puccini's style is one that was once treated dismissively by musicologists;

this can be attributed to a perception that his work, with its emphasis

on melody and evident popular appeal, lacked "depth." Comments,

however, have been contradictory with some critics telling us that it

was only his theatrical flair that made him successful while others

have said that he was never a great theatrical composer. The answer to

this determined antipathy may well be that there have always been

critics who resent a composer who becomes popular. Despite the place

Puccini clearly occupies in the popular tradition of Verdi, his style

of orchestration also shows the strong influence of Wagner,

matching specific orchestral configurations and timbres to different

dramatic moments. His operas contain an unparalleled manipulation of

orchestral colors, with the orchestra often creating the scene's

atmosphere. The

structures of Puccini's works are also noteworthy. While it is to an

extent possible to divide his operas into arias or numbers (like

Verdi's), his scores generally present a very strong sense of

continuous flow and connectivity, perhaps another sign of Wagner's

influence. Like Wagner, Puccini used leitmotifs to connote characters and sentiments (or combinations thereof). This is most apparent in Tosca,

where the three chords which signal the beginning of the opera are used

throughout to announce Scarpia; the descending brass motive (Vivacissimo con violenza)

is connected to the repressive regime which ruled Rome at the setting

of the opera and most clearly to Angelotti, one of the regime's

victims; the harp arpeggio figure which appears at Tosca's entrance and

the aria Vissi d'arte symbolizing

Tosca's religious fervor; the clarinet ascending - descending scale

indicating Mario's suffering and his doomed love for Tosca. Several

motifs are also linked to Mimi and the bohemians in La bohème and to Cio-Cio-San's eventual suicide in Butterfly.

Unlike Wagner, though, Puccini's motifs are static: where Wagner's

motifs develop into more complicated figures as the characters develop,

Puccini's remain more or less identical throughout the opera (in this

respect anticipating the themes of modern musical theatre). Another distinctive quality in Puccini's works is the use of the voice in the style of speech i.e. canto parlando;

characters sing short phrases one after another as if they were in

conversation. Puccini is also celebrated for his melodic gift and many

of his melodies are both memorable and enduringly popular. At their

simplest these melodies are made of sequences from the scale, a very

distinctive example being Quando me'n vo' (Musetta's Waltz) from La bohème and E lucevan le stelle from Act III of Tosca. Today, it is rare not to find at least one Puccini aria included in an operatic singer's CD album or recital. Unusual

for operas written by Italian composers up until that time, many of

Puccini’s operas are set outside Italy — in exotic places such as Japan (Madama Butterfly), gold-mining country in California (La fanciulla del West), Paris and the Riviera (La rondine), and China (Turandot). Pulitzer Prize winning music critic Lloyd Schwartz summarized

Puccini thus: "Is it possible for a work of art to seem both completely

sincere in its intentions and at the same time counterfeit and

manipulative? Puccini built a major career on these contradictions. But

people care about him, even admire him, because he did it both so

shamelessly and so skillfully. How can you complain about a composer

whose music is so relentlessly memorable, even — maybe especially — at

its most saccharine?"