<Back to Index>

- Anatomist Andreas Vesalius, 1514

- Writer Marie Catherine Sophie de Flavigny, Comtesse d'Agoult (Daniel Stern), 1805

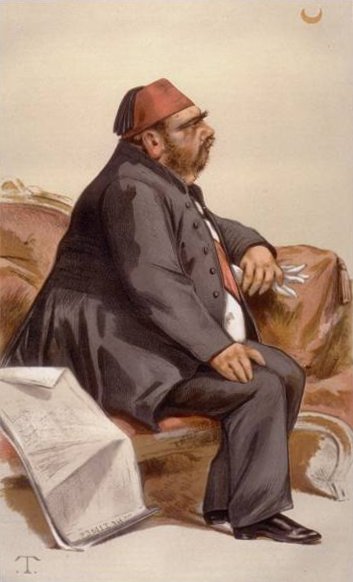

- Khedive of Egypt and Sudan Ismail Pasha, 1830

PAGE SPONSOR

Isma'il Pasha (İsmail Paşa in Turkish), known as Ismail the Magnificent (Arabic: إسماعيل باشا) (December 31, 1830 – March 2, 1895), was a Wāli and subsequently Khedive of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 until he was removed at the behest of the British in 1879. While in power he greatly modernized Egypt and Sudan, but also put the country heavily in debt. His philosophy can be glimpsed in a statement he made in 1879: "My country (Egypt) is no longer in Africa; we are now part of Europe. It is therefore natural for us to abandon our former ways and to adopt a new system adapted to our social conditions."

Ismail, of Albanian descent, was born in Cairo at Al Musafir Khana Palace being the second of the three sons of Ibrahim Pasha and grandson of Muhammad Ali. His mother was Hoshiar (Khushiyar), third wife of his father. She was reportedly a sister of Pertevniyal Valide Sultan (1812 - 1883). Pertevniyal was a wife of Mahmud II of the Ottoman Empire and mother of Abdülaziz I.

After receiving a European education in Paris, where he attended the École d'état-major, he returned home, and on the death of his elder brother became heir to his uncle, Said I, the Wāli of Egypt and Sudan. Said, who apparently conceived his own safety to lie in ridding himself as much as possible of the presence of his nephew, employed him in the next few years on missions abroad, notably to the Pope, the Emperor Napoleon III and the Sultan of Ottoman Empire. In 1861 he was dispatched at the head of an army of 18,000 to quell an insurrection in Sudan, and this he successfully accomplished.

After the death of Said, Ismail was proclaimed wāli on January 19, 1863. Like all Egyptian rulers since his grandfather Muhammad Ali, he claimed the higher title of Khedive, which the Ottoman Porte had consistently refused to sanction. However, in 1867, Isma'il succeeded in persuading the Ottoman Sultan Abdülaziz to grant a firman finally recognizing him as Khedive in exchange for an increase in the tribute. Another firman changed the law of succession to direct descent from father to son rather than brother to brother, and a further decree in 1873 confirmed the virtual independence of the Khedivate of Egypt from the Porte.

Ismail launched vast schemes of internal reform on the scale of his grandfather, remodeling the customs system and the post office, stimulating commercial progress, creating a sugar industry, building palaces, entertaining lavishly and maintaining an opera and a theatre. He greatly expanded Cairo, building an entire new city on its western edge modeled on Paris. Alexandria was also improved. He launched a vast railroad building project that saw Egypt and Sudan rise from having virtually none to the most railways per habitable kilometer of any nation in the world.

One of his most significant achievements was to establish an assembly of delegates in November 1866. Though this was supposed to be a purely advisory body, its members eventually came to have an important influence on governmental affairs. Village headmen dominated the assembly and came to exert increasing political and economic influence over the countryside and the central government. This was shown in 1876, when the assembly persuaded Ismail to reinstate the law (enacted by him in 1871 to raise money and later repealed) that allowed landownership and tax privileges to persons paying six years' land tax in advance.

Ismail tried to reduce slave trading and extended Egypt's rule in Africa. In 1874 he annexed Darfur, but was prevented from expanding into Ethiopia after his army was repeatedly defeated by Emperor Yohannes IV, first at Gund at 16 November 1875, and again at Gura in March of the following year.

Ismail dreamt of expanding his realm over the whole Nile including its diverse sources and over the whole African coast of the Red Sea. This, together with rumours about rich raw material and fertile soil, led Ismail to expansive policies directed against Ethiopia under the Emperor Yohannes IV. In 1865 the Ottoman Sublime Porte ceded the Ottoman Province of Habesh (with Massawa and Sawak in at the Red Sea as the main cities of that province) to Ismail. This province, neighbor of Ethiopia, first consisted of a coastal strip only, but expanded subsequently inland into territory controlled by the Ethiopian ruler. Here Ismail occupied regions originally claimed by the Ottomans when they had established the province (eyaleti) of Habesh in the 16th century. New economically promising projects, like huge cotton plantations in the Barka, were started. In 1872 Bogos (with the city of Keren) was annexed by the governor of the new "Province of Eastern Sudan and the Red Sea Coast", Werner Munzinger Pasha. In October 1875 Ismail's army occupied the adjacent highlands of Hamasien, which were then tributary to the Ethiopian Emperor. In November this army was virtually annihilated during the battle of Dogali near the Mereb river. In March 1876 Ismail's army again suffered a dramatic defeat after an attack by Yohannes's army at Gura'. Ismail's son Hassan was captured by the Ethiopians and only released after a large ransom. This was followed by a long cold war, only finishing in 1884 with the Anglo - Egyptian - Ethiopian Hewett Treaty, when Bogos was given back to Ethiopia. The Red Sea Province created by Ismail and his governor Munzinger Pasha was taken over by the Italians shortly thereafter and became the territorial basis for the Colonia Eritrea (proclaimed in 1890).

Ismail's khedivate is closely connected to the building of the Suez Canal.

He agreed to, and oversaw, the Egyptian portion of its construction. On

his accession, he refused to ratify the concessions to the Canal

company made by Said, and the question was referred in 1864 to the

arbitration of Napoleon III, who awarded £ 3,800,000 to the

company as compensation for the losses they would incur by the changes

which Ismail insisted upon in the original grant. Ismail then used

every available means, by his own undoubted powers of fascination and

by judicious expenditure, to bring his personality before the foreign

sovereigns and public, and he had much success. In 1867 he visited

Paris and London, where he was received by Queen Victoria and welcomed by the Lord Mayor. Whilst in England he also saw a Royal Navy Fleet Review with the Ottoman Sultan.

In 1869 he again paid a visit to England. When the canal finally

opened, Ismail held a festival of unprecedented scope, inviting

dignitaries from around the world. These

developments - especially the costly war with Ethiopia - left Egypt in

deep debt to the European powers, and they used this position to wring

concessions out of Ismail. One of the most unpopular among Egyptians

was the new system of mixed courts,

by which Europeans were tried by judges from their own nation. But at

length the inevitable financial crisis came. A national debt of over

one hundred million pounds sterling (as opposed to three millions when

he became viceroy) had been incurred by the khedive, whose fundamental

idea of liquidating his borrowings was to borrow at increased interest.

The bond-holders became restive. Judgments were given against the

Khedive in the international tribunals. When he could raise no more

loans, he sold his Suez Canal shares (in 1875) to the British Government for only £ 3,976,582; this was immediately followed by the beginning of foreign intervention. In December 1875, Stephen Cave was

sent out by the British government to inquire into the finances of

Egypt, and in April 1876 his report was published, advising that in

view of the waste and extravagance it was necessary for foreign Powers

to interfere in order to restore credit. The result was the

establishment of the Caisse de la Dette. In October, George Goschen and

Joubert made a further investigation, which resulted in the

establishment of Anglo - French control over finances and the government.

A further commission of inquiry by Major Baring (afterwards

1st Earl of Cromer) and others in 1878 culminated in Ismail making over

his estates to the nation and accepting the position of a

constitutional sovereign, with Nubar as premier, Charles Rivers Wilson as finance minister, and de Blignières as minister of public works.

This control of the country was unacceptable to many Egyptians, who united behind a disaffected Colonel Ahmed Urabi. The Urabi Revolt consumed

Egypt. Hoping the revolt could relieve him of European control, Ismail

did little to oppose Urabi and gave into his demands to dissolve the

government. The British Empire and France took

the matter seriously, and insisted in May 1879 on the reinstatement of

the British and French ministers. With the country largely in the hands

of Urabi, Ismail could not agree, and had little interest in doing so.

As a result, the British and French governments pressured the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II to depose Ismail Pasha, and this was done on June 26, 1879. The more pliable Tewfik Pasha, Ismail's son, was made his successor. Ismail Pasha left Egypt and initially went into exile to Naples, but was eventually permitted by Sultan Abdülhamid II to retire to his Palace of Emirgan on the Bosporus in Istanbul. There he remained, more or less a state prisoner, until his death. He was later buried in Cairo.