<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Gaston Maurice Julia, 1893

- Composer Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, 1809

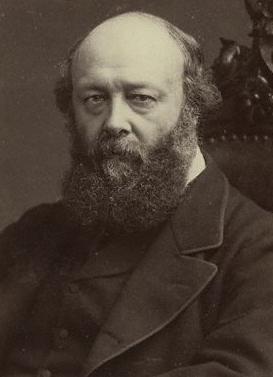

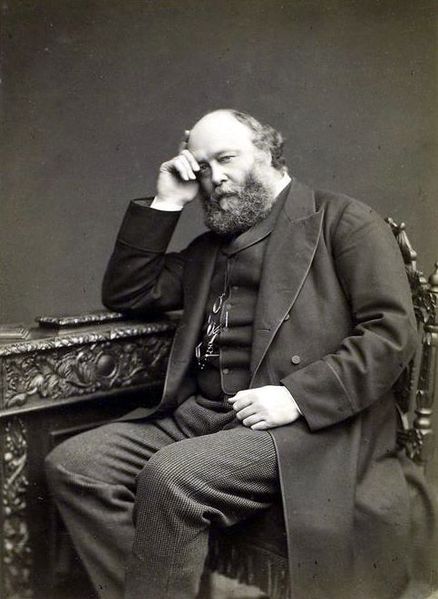

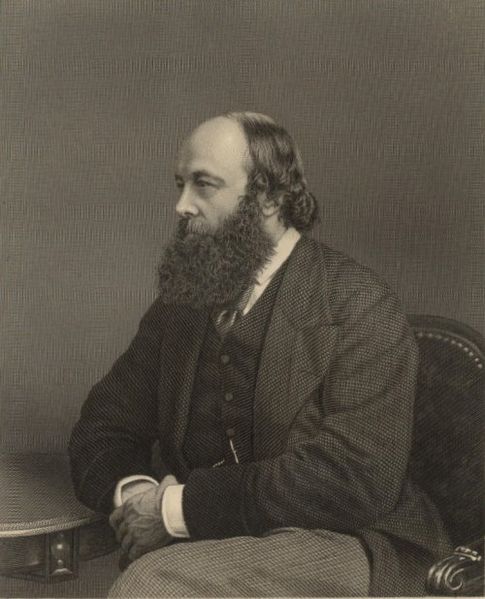

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, 1830

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, KG, GCVO, PC (3 February 1830 – 22 August 1903), known as Lord Robert Cecil before 1865 and as Viscount Cranborne from 1865 until 1868, was a British Conservative statesman and thrice Prime Minister, serving for a total of over 13 years. He was the first British Prime Minister of the 20th century and the last Prime Minister to head his full administration from the House of Lords.

Lord Robert Cecil was first elected to the House of Commons in 1854 and served as Secretary of State for India in Lord Derby's Conservative government from 1866 until his resignation in 1867 over its introduction of Benjamin Disraeli's Reform Bill that

extended the suffrage to working-class men. In 1868 upon the death of

his father, Cecil was elevated to the House of Lords. In 1874 when

Disraeli formed an administration Salisbury returned as Secretary of

State for India and in 1878 was appointed Foreign Secretary and played

a leading part in the Congress of Berlin, despite doubts over Disraeli's pro-Ottoman policy. After the Conservatives lost the1880 election and Disraeli's death the year after, Salisbury emerged as Conservative leader in the House of Lords, with Sir Stafford Northcote leading the party in the Commons. He became Prime Minister in June 1885 when the Liberal leader William Ewart Gladstone resigned, and he held the office until January 1886. When Gladstone came out in favour of Home Rule for Ireland, Salisbury opposed him and formed an alliance with the breakaway Liberal Unionists and he won the subsequent general election.

He remained Prime Minister until Gladstone's Liberals formed a

government with the support of the Irish Nationalist Party, despite the

Unionists gaining the largest number of votes and seats in the 1892 general election. However the Liberals lost the 1895 general election and Salisbury once again became Prime Minister, leading the Unionists to war against the Boers and another electoral victory in 1900 before relinquishing the premiership to his nephew Arthur Balfour. He died a year after in 1903. Lord Robert Cecil was the second son of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury. In 1840 he went to Eton College, where he did well in French, German, the classics and theology. However he left in 1845 due to intense bullying. In December 1847 he went to Christ Church, Oxford although he received an honorary fourth class in mathematics conferred by nobleman's privilege due to ill health. Whilst at Oxford he associated himself with the Tractarian movement. In April 1850 he joined Lincoln's Inn but subsequently did not enjoy law. His doctor advised him to travel for his health and so in July 1851 to May 1853 Cecil travelled through Cape Colony, Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand. He

disliked the Boers and wrote that free institutions and self-government

could not be granted to the Cape Colony because the Boers outnumbered

the British three-to-one and "it will simply be delivering us over

bound hand and foot into the power of the Dutch, who hate us as much as

a conquered people can hate their conquerors". He

found the Kaffirs "a fine set of men – whose language bears traces of a

very high former civilisation", similar to Italian. They were "an

intellectual race, with great firmness and fixedness of will" but

"horribly immoral" as they lacked theism. In the Bendigo goldmine

of Australia he claimed that "there is not half as much crime or

insubordination as there would be in an English town of the same wealth

and population". 10,000 miners were policed by four men armed with

carbines and at Mount Alexander 30,000

people were protected by 200 policemen, with over 30,000 ounces of gold

mined per week. He believed that there was "generally far more civility

than I should be likely to find in the good town of Hatfield" and

claimed this was due to "the government was that of the Queen, not of

the mob; from above, not from below. Holding from a supposed right

(whether real or not, no matter) and from “the People the source of all

legitimate power”." Cecil said of the Maori of

New Zealand: "The natives seem when they have converted to make much

better Christians than the white man". A Maori chief offered Cecil five

acres near Auckland, which he declined. He entered the House of Commons as a Conservative in 1853, as MP for Stamford in Lincolnshire.

He retained this seat until entering the peerage and it was not

contested during his time as its representative. In his election

address he opposed secular education and "ultramontane"

interference with the Church of England which was "at variance with the

fundamental principles of our constitution". He would oppose "any such

tampering with our representative system as shall disturb the

reciprocal powers on which the stability of our constitution rests". In 1867, after his brother Eustace complained

of being addressed by constituents in a hotel, Cecil responded: "A

hotel infested by influential constituents is worse than one infested

by bugs. It's a pity you can't carry around a powder insecticide to get

rid of vermin of that kind". In December 1856 Cecil began publishing articles for the Saturday Review,

which he contributed anonymously for the next nine years. From 1861 to

1864 he published 422 articles in it, in total the weekly published 608

of his articles. The Quarterly Review was the foremost intellectual journal of the age and of the twenty-six

issues published between spring 1860 and summer 1866, Cecil had

anonymous articles in all but three of them. He also wrote lead

articles for the Tory daily newspaper the Standard. In 1859 Cecil was a founding co-editor of Bentley's Quarterly Review, with J.D. Cook and Rev. William Scott, but this closed after four issues. Salisbury criticised the foreign policy of Lord John Russell,

claiming he was "always being willing to sacrifice anything for

peace ... colleagues, principles, pledges ... a portentous mixture of

bounce and baseness ... dauntless to the weak, timid and cringing to the

strong". The lessons to be learnt from Russell's foreign policy,

Salisbury believed, were that he should not listen to the Opposition of

the press otherwise "we are to be governed ... by a set of weathercocks,

delicately poised, warranted to indicate with unnerving accuracy every

variation in public feeling". Secondly: "No one dreams of conducting

national affairs with the principles which are prescribed to

individuals. The meek and poor-spirited among nations are not to be

blessed, and the common sense of Christendom has always prescribed for

national policy principles diametrically opposed to those that are laid

down in the Sermon on the Mount".

Thirdly: "The assemblies that meet in Westminster have no jurisdiction

over the affairs of other nations. Neither they nor the Executive,

except in plain defiance of international law, can interfere [in the

internal affairs of other countries] ... It is not a dignified position

for a Great Power to occupy, to be pointed out as the busybody of

Christendom". Finally, Britain should not threaten other countries

unless prepared to back this up by force: "A willingness to fight is the point d'appui of

diplomacy, just as much as a readiness to go to court is the starting

point of a lawyer's letter. It is merely courting dishonour, and

inviting humiliation for the men of peace to use the habitual language

of the men of war". In 1866 Lord Robert, now Viscount Cranborne after the death of his older brother, Cranborne entered the third government of Lord Derby as Secretary of State for India. When in 1867 John Stuart Mill proposed a type of proportional representation,

Cranborne argued that: "It was not of our atmosphere — it was not in

accordance with our habits; it did not belong to us. They all knew that

it could not pass. Whether that was creditable to the House or not was

a question into which he would not inquire; but every Member of the

House the moment he saw the scheme upon the Paper saw that it belonged

to the class of impracticable things". On 2 August when the Commons debated the Orissa famine in India, Cranborne spoke out against experts, political economy, and the government of Bengal. Utilising the Blue Books,

Cranborne criticised officials for "walking in a dream ... in superb

unconsciousness, believing that what had been must be, and that as long

as they did nothing absolutely wrong, and they did not displease their

immediate superiors, they had fulfilled all the duties of their

station". These officials worshipped political economy "as a sort of

“fetish” ... [they] seemed to have forgotten utterly that human life was

short, and that man did not subsist without food beyond a few days".

Three quarters of a million people had died because officials had

chosen "to run the risk of losing the lives than to run the risk of

wasting the money". Cranborne's speech was received with "an

enthusiastic, hearty cheer from both sides of the House" and Mill

crossed the floor of the Commons to congratulate him on it. The famine

left Cranborne with a lifelong suspicion of experts and in the

photograph albums at his home covering the years 1866-67 there are two

images of skeletal Indian children amongst the family pictures.

When

parliamentary reform came to prominence again in the mid-1860s,

Cranborne worked hard to master electoral statistics until he became an

expert. When the Liberal Reform Bill was being debated in 1866,

Cranborne studied the census returns to see how each clause in the Bill

would affect the electoral prospects in each seat. Cranborne

did not expect Disraeli's conversion to reform, however. When the

Cabinet met on 16 February 1867, Disraeli voiced his support for some

extension of the suffrage, providing statistics amassed by Robert Dudley Baxter,

showing that 330,000 people would be given the vote and all except

60,000 would be granted extra votes. Cranborne studied Baxter's

statistics and on 21 February he met Lord Carnarvon,

who wrote in his diary: "He is firmly convinced now that Disraeli has

played us false, that he is attempting to hustle us into his measure,

that Lord Derby is in his hands and that the present form which the

question has now assumed has been long planned by him". They agreed to

"a sort of offensive and defensive alliance on this question in the

Cabinet" to "prevent the Cabinet adopting any very fatal course".

Disraeli had "separate and confidential conversations ... carried on

with

each member of the Cabinet from whom he anticipated opposition [which]

had divided them and lulled their suspicions". That

same night Cranborne spent three hours studying Baxter's statistics and

wrote to Carnarvon the day after that although Baxter was right overall

in claiming that 30% of £10 rate payers who qualified for the vote

would not register, it would be untrue in relation to the smaller

boroughs where the register is kept up to date. Cranborne also wrote to

Derby arguing that he should adopt 10 shillings rather than Disraeli's

20 shillings for the qualification of the payers of direct taxation:

"Now above 10 shillings you won't get in the large mass of the

£20 householders. At 20 shillings I fear you won't get more than

150,000 double voters, instead of the 270,000 on which we counted. And

I fear this will tell horribly on the small and middle-sized boroughs". On

23 February Cranborne protested in Cabinet and the next day analysed

Baxter's figures using census returns and other statistics to determine

how Disraeli's planned extension of the franchise would affect

subsequent elections. Cranborne found that Baxter had not taken into

account the different types of boroughs in the totals of new voters. In

small boroughs under 20,000 the "fancy franchises" for direct taxpayers

and dual voters would be less than the new working-class voters in each

seat. The same day he met Carnarvon and they both studied the figures,

coming to the same result each time: "A complete revolution would be

effected in the boroughs" due to the new majority of the working-class

electorate. Cranborne wanted to send his resignation to Derby along

with the statistics but Cranborne agreed to Carnarvon's suggestion that

as a Cabinet member he had a right to call a Cabinet meeting. It was

planned for the next day, 25 February. Cranborne wrote to Derby that he

had discovered that Disraeli's plan would "throw the small boroughs

almost, and many of them entirely, into the hands of the voter whose

qualification is less than £10. I do not think that such a

proceeding is for the interest of the country. I am sure that it is not

in accordance with the hopes which those of us who took an active part

in resisting Mr Gladstone's Bill last year in those whom we induced to

vote for us". The Conservative boroughs with populations less than

25,000 (a majority of the boroughs in Parliament) would be very much

worse off under Disraeli's scheme than the Liberal Reform Bill of the

previous year: "But if I assented to this scheme, now that I know what

its effect will be, I could not look in the face those whom last year I

urged to resist Mr Gladstone. I am convinced that it will, if passed,

be the ruin of the Conservative party". When

Cranborne entered the Cabinet meeting on 25 February "with reams of

paper in his hands" he begun by reading statistics but was interrupted

to be told of the proposal by Lord Stanley that

they should agree to a £6 borough rating franchise instead of the

full household suffrage, and a £20 county franchise rather than

£50. The Cabinet agreed to Stanley's proposal. The meeting was so

contentious that a minister who was late initially thought they were

debating the suspension of habeas corpus. The

next day another Cabinet meeting took place, with Cranborne saying

little and the Cabinet adopting Disraeli's proposal to bring in a Bill in a week's time. On 28 February a meeting of the Carlton Club took

place, with a majority of the 150 Conservative MPs present supporting

Derby and Disraeli. At the Cabinet meeting on 2 March, Cranborne,

Carnarvon and General Peel were pleaded with for two hours to not

resign but when Cranborne "announced his intention of resigning ... Peel

and Carnarvon, with evident reluctance, followed his example". John Manners observed

that Cranborne "remained unmoveable". Derby closed his red box with a

sigh and stood up, saying "The Party is ruined!" Cranborne got up at

the same time, with Peel remarking: "Lord Cranborne, do you hear what

Lord Derby says?" Cranborne ignored this and the three resigning

ministers left the room. Cranborne's resignation speech was met with

loud cheers and Carnarvon observed that it was "moderate and in good

taste – a sufficient justification for us who seceded and yet no

disclosure of the frequent changes in policy in the Cabinet". Disraeli

introduced his Bill on 18 March and it would extend the suffrage to all

rate-paying householders of two years' residence, dual voting for

graduates or those of a learned profession, or those with £50 in

governments funds or in the Bank of England or a savings bank. These

"fancy franchises", as Cranborne had foreseen, did not survive the

Bill's course through Parliament; dual voting was dropped in March, the

compound householder vote in April; and the residential qualification

was reduced in May. In the end the county franchise was granted to

householders rated at £12 annually. On

15 July the third reading of the Bill took place and Cranborne spoke

first, in a speech which his biographer Andrew Roberts has called

"possibly the greatest oration of a career full of powerful

parliamentary speeches". Cranborne

observed how the Bill "bristled with precautions, guarantees and

securities" had been stripped of these. He attacked Disraeli by

pointing out how he had campaigned against the Liberal Bill in 1866 yet

the next year introduced a Bill more extensive than the one rejected. In his article for the October Quarterly Review,

entitled ‘The Conservative Surrender’, Cranborne criticised Derby

because he had "obtained the votes which placed him in office on the

faith of opinions which, to keep office, he immediately repudiated ... He

made up his mind to desert these opinions at the very moment he was

being raised to power as their champion". Also, the annals of modern

parliamentary history could find no parallel for Disraeli's betrayal;

historians would have to look "to the days when Sunderland directed the Council, and accepted the favours of James when he was negotiating the invasion of William". Disraeli responded in a speech that Cranborne was "a very clever man who has made a very great mistake".

In 1868, on the death of his father, he inherited the Marquessate of Salisbury, thereby becoming a member of the House of Lords. From 1868 and 1871, he was chairman of the Great Eastern Railway, which was then experiencing losses. During his tenure, the company was taken out of chancery, and paid out a small dividend on its ordinary shares.

He returned to government in 1874, serving once again as India Secretary in the government of Benjamin Disraeli, and Britain's Ambassador Plenipotentiary at the 1876 Constantinople Conference. Salisbury gradually developed a good relationship with Disraeli, whom he had previously disliked and mistrusted. In 1878, Salisbury succeeded Lord Derby (son of the former Prime Minister) as Foreign Secretary in time to help lead Britain to "peace with honour" at the Congress of Berlin. For this he was rewarded with the Order of the Garter. Following

Disraeli's death in 1881, the Conservatives entered a period of

turmoil. Salisbury became the leader of the Conservative members of the

House of Lords, though the overall leadership of the party was not

formally allocated. So he struggled with the Commons leader Sir Stafford Northcote, a struggle in which Salisbury eventually emerged as the leading figure. In 1884 Gladstone introduced a Reform Bill which

would extend the suffrage to two million rural workers. Salisbury and

Northcote agreed that any Reform Bill would be supported only if a

parallel redistributionary measure was introduced as well. In a speech

in the Lords, Salisbury claimed: "Now that the people have in no real

sense been consulted, when they had, at the last General Election, no

notion of what was coming upon them, I feel that we are bound, as

guardians of their interests, to call upon the government to appeal to

the people, and by the result of that appeal we will abide". The Lords

rejected the Bill and Parliament was prorogued for ten weeks. Writing to Canon Malcolm MacColl,

Salisbury believed that Gladstone's proposals for reform without

redistribution would mean "the absolute effacement of the Conservative

Party. It would not have reappeared as a political force for thirty

years. This conviction ... greatly simplified for me the computation of

risks". At a meeting of the Carlton Club on 15 July, Salisbury

announced his plan for making the government introduce a Seats (or

Redistribution) Bill in the Commons whilst at the same time delaying a

Franchise Bill in the Lords. The unspoken implication being that

Salisbury would relinquish the party leadership if his plan was not

supported. Although there was some dissent, Salisbury carried the party

with him. Salisbury

wrote to Lady John Manners on 14 June that he did not regard female

suffrage as a question of high importance "but when I am told that my

ploughmen are capable citizens, it seems to me ridiculous to say that

educated women are not just as capable. A good deal of the political

battle of the future will be a conflict between religion and unbelief:

& the women will in that controversy be on the right side". On 21 July a large meeting for reform was held at Hyde Park. Salisbury said in The Times that

"the employment of mobs as an instrument of public policy is likely to

prove a sinister precedent". On 23 July at Sheffield, Salisbury said

that the government "imagine that thirty thousand Radicals going to

amuse themselves in London on a given day expresses the public opinion

of the day ... they appeal to the streets, they attempt legislation by

picnic". Salisbury further claimed that Gladstone adopted reform as a

"cry" to deflect attention from his foreign and economic policies at

the next election. He claimed that the House of Lords was protecting

the British constitution: "I do not care whether it is an hereditary

chamber or any other – to see that the representative chamber does not

alter the tenure of its own power so as to give a perpetual lease of

that power to the party in predominance at the moment". On 25 July at a

reform meeting in Leicester consisting of 40,000 people, Salisbury was

burnt in effigy and a banner quoted Shakespeare's Henry VI:

"Old Salisbury – shame to thy silver hair, Thou mad misleader". On 9

August in Manchester over 100,000 came to hear Salisbury speak. On 30

September at Glasgow he said: "We wish that the franchise should pass

but that before you make new voters you should determine the

constitution in which they are to vote". Salisbury published an article in the National Review for

October, titled ‘The Value of Redistribution: A Note on Electoral

Statistics’. He claimed that the Conservatives "have no cause, for

Party reasons, to dread enfranchisement coupled with a fair

redistribution". Judging by the 1880 results, Salisbury asserted that

the overall loss to the Conservatives of enfranchisement without

redistribution would be 47 seats. Salisbury spoke throughout Scotland

and claimed that the government had no mandate for reform when it had

not appealed to the people. Gladstone

offered wavering Conservatives a compromise a little short of

enfranchisement and redistribution, and after the Queen unsuccessfully

attempted to persuade Salisbury to compromise, he wrote to Rev. James

Baker on 30 October: "Politics stand alone among human pursuits in this

characteristic, that no one is conscious of liking them – and no one is

able to leave them. But whatever affection they may have had they are

rapidly losing. The difference between now and thirty years ago when I

entered the House of Commons is inconceivable". On 11 November the

Franchise Bill received its third reading in the Commons and it was due

to get a second reading in the Lords. The day after at a meeting of

Conservative leaders, Salisbury was outnumbered in his opposition to

compromise. On 13 February Salisbury rejected MacColl's idea that he

should meet Gladstone, as he believed the meeting would be found out

and that Gladstone had no genuine desire to negotiate. On 17 November

it was reported in the newspapers that if the Conservatives gave

"adequate assurance" that the Franchise Bill would pass the Lords

before Christmas the government would ensure that a parallel Seats Bill

would receive its second reading in the Commons as the Franchise Bill

went into committee stage in the Lords. Salisbury responded by agreeing

only if the Franchise Bill came second. The Carlton Club met to discuss the situation, with Salisbury's daughter writing: The

three arch-funkers Cairns, Richmond and Carnarvon cried out declaring

that he would accept no compromise at all as it was absurd to imagine

the Government conceding it. When the discussion was at its height

(very high) enter Arthur [Balfour] with explicit declamation dictated

by G.O.M. in Hartington's handwriting yielding the point entirely.

Tableau and triumph along the line for the ‘stiff’ policy which had

obtained terms which the funkers had not dared hope for. My father's

prevailing sentiment is one of complete wonder ... we have got all and

more than we demanded. Despite

the controversy which had raged, the meetings of leading Liberals and

Conservatives on reform at Downing Street were amicable. Salisbury and

the Liberal Sir Charles Dilke dominated

discussions as they had both closely studied in detail the effects of

reform on the constituencies. After one of the last meetings on 26

November, Gladstone told his secretary that "Lord Salisbury, who seems

to monopolise all the say on his side, has no respect for tradition. As

compared with him, Mr Gladstone declares he is himself quite a

Conservative. They got rid of the boundary question, minority

representation, grouping and the Irish difficulty. The question was

reduced to ... for or against single member constituencies". The Reform Bill laid

down that the majority of the 670 constituencies were to be roughly

equal size and return one member; those between 50,000 and 165,000 kept

the two-member representation and those over 165,000 and all the

counties were split up into single-member constituencies. This

franchise existed until 1918. He became Prime Minister of a minority administration from 1885 to 1886. In the November 1883 issue of National Review Salisbury wrote an article titled "Labourers' and Artisans' Dwellings" in which

he argued that the poor conditions of working class housing were

injurious to morality and health. Salisbury said "Laissez-faire is an admirable doctrine but it must be applied on both sides", as Parliament had enacted new building projects (such as the Thames Embankment)

which had displaced working class people and was responsible for

"packing the people tighter": "... thousands of families have only a

single room to dwell in, where they sleep and eat, multiply, and

die ... It is difficult to exaggerate the misery which such conditions of

life must cause, or the impulse they must give to vice. The depression

of body and mind which they create is an almost insuperable obstacle to

the action of any elevating or refining agencies". The Pall Mall Gazette argued that Salisbury had sailed into "the turbid waters of State Socialism"; the Manchester Guardian said his article was "State socialism pure and simple" and The Times claimed Salisbury was "in favour of state socialism". In July 1885 the Housing of the Working Classes Bill was introduced by Cross in the Commons and Salisbury in the Lords. When Lord Wemyss criticised

the Bill as "strangling the spirit of independence and the

self-reliance of the people, and destroying the moral fibre of our race

in the anaconda coils of state socialism", Salisbury responded: "Do not

imagine that by merely affixing to it the reproach of Socialism you can

seriously affect the progress of any great legislative movement, or

destroy those high arguments which are derived from the noblest

principles of philanthropy and religion". Although unable to accomplish much due to his lack of a parliamentary majority, the split of the Liberals over Irish Home Rule in

1886 enabled him to return to power with a majority, and, excepting a

Liberal minority government (1892 – 1895), to serve as Prime Minister

from 1886 to 1892. In 1889 Salisbury set up the London County Council and

then in 1890 allowed it to build houses. However he came to regret

this, saying in November 1894 that the LCC, "is the place where

collectivist and socialistic experiments are tried. It is the place

where a new revolutionary spirit finds its instruments and collects its

arms". Salisbury caused controversy in 1888 after Gainsford Bruce had won the Holborn by-election for the Unionists, beating the Liberal Earl Compton. Bruce had won the seat with a smaller majority than Francis Duncan had

for the Unionists in 1885. Salisbury explained this by saying in a

speech in Edinburgh on 30 November: "But then Colonel Duncan was

opposed to a black man, and, however great the progress of mankind has

been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudices, I

doubt if we have yet got to the point where a British constituency will

elect a black man to represent them ... I am speaking roughly and using

language in its colloquial sense, because I imagine the colour is not

exactly black, but at all events, he was a man of another race". The

"black man" was Dadabhai Naoroji,

an Indian. Salisbury's comments were criticised by the Queen and by

Liberals who believed that Salisbury had suggested that only white

Britons could represent a British constituency. Three weeks later

Salisbury delivered a speech at Scarborough, where he denied that "the

word “black” necessarily implies any contemptuous denunciation. Such a

doctrine seems to be a scathing insult to a very large proportion of

the human race ... The people whom we have been fighting at Suakim, and

whom we have happily conquered, are among the finest tribes in the

world, and many of them are as black as my hat". Furthermore "such

candidatures are incongruous and unwise. The British House of Commons,

with its traditions ... is a machine too peculiar and too delicate to

be

managed by any but those who have been born within these isles".

Naoroji was elected for Finsbury in 1892 and Salisbury invited him to

become a Governor of the Imperial Institute, which he accepted. Salisbury's government passed the Naval Defence Act 1889 which facilitated the spending of an extra £20 million on the Royal Navy over the following four years. This was the biggest ever expansion of the navy in peacetime: ten new battleships, thirty-eight new cruisers, eighteen new torpedo boats and four new fast gunboats. Traditionally (since the Battle of Trafalgar) Britain had possessed a navy one-third larger than their nearest naval rival but now the Royal Navy was set to the Two-Power Standard;

that it would be maintained "to a standard of strength equivalent to

that of the combined forces of the next two biggest navies in the

world". This was aimed at France and Russia. In the aftermath of the general election of 1892,

Balfour and Chamberlain wished to pursue a programme of social reform,

which Salisbury believed would alienate "a good many people who have

always been with us" and that "these social questions are destined to

break up our party". When

the Liberals and Irish Nationalists (which were a majority in the new

Parliament) successfully voted against the government, Salisbury

resigned the premiership on 12 August. His private secretary at the

Foreign Office wrote that Salisbury "shewed indecent joy at his

release". Salisbury — in an article in November for the National Review entitled ‘Constitutional revision’ — said that the new government, lacking a

majority in England and Scotland, had no mandate for Home Rule and

argued that because there was no referendum only the House of Lords

could provide the necessary consultation with the nation on policies

for organic change. The

Lords defeated the second Home Rule Bill by 419 to 41 in September 1893

but Salisbury stopped them from opposing the Liberal Chancellor's death

duties in 1894. The general election of 1895 returned a large Unionist majority. Salisbury's expertise was in foreign affairs. For most of his time as Prime Minister he served not as First Lord of the Treasury, the traditional position held by the Prime Minister, but as Foreign Secretary. In that capacity, he managed Britain's foreign affairs, famously pursuing a policy of "Splendid Isolation". Among the important events of his premierships was the Partition of Africa, culminating in the Fashoda Crisis and the Second Boer War.

At home he sought to "fight Home Rule with kindness" by launching a

land reform programme which helped hundreds of thousands of Irish

peasants gain land ownership. On

11 July 1902, in failing health and broken hearted over the death of

his wife, Salisbury resigned. He was succeeded by his nephew, Arthur James Balfour. Salisbury was offered a dukedom by Queen Victoria in

1886 and 1892, but declined both offers, citing the prohibitive cost of

the lifestyle dukes were expected to maintain. When Salisbury died his

estate was probated at 310,336 pounds sterling. In 1900 Salisbury was

worth £6.56 million, about £374 million in 2005 prices. Salisbury is seen as an icon of traditional, aristocratic conservatism. The Conservative historian Robert Blake considered Salisbury "the most formidable intellectual figure that the Conservative party has ever produced". In 1977 the Salisbury Group was founded, chaired by Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 6th Marquess of Salisbury and named after the 3rd Marquess. It published pamphlets advocating conservative policies. The academic quarterly Salisbury Review was named in his honour upon its founding in 1982. The Conservative historian Maurice Cowling claimed that "The giant of conservative doctrine is Salisbury". It was on Cowling's suggestion that Paul Smith edited a collection of Salisbury's articles from the Quarterly Review. Andrew

Jones and Michael Bentley wrote in 1978 that "historical inattention"

to Salisbury "involves wilful dismissal of a Conservative tradition

which recognizes that threat to humanity when ruling authorities engage

in democratic flattery and the threat to liberty in a competitive rush of legislation". Not long before his death in 1967, Clement Attlee (Labour Party Prime Minister, 1945 – 1951) was invited to Chequers by Harold Wilson and was asked who he thought was the best Prime Minister of his lifetime. Attlee immediately replied: "Salisbury". The 6th Marquess of Salisbury commissioned Andrew Roberts to write Salisbury's authorised biography, which was published in 1999. After the Bering Sea Arbitration, Canadian Prime Minister Sir John Sparrow David Thompson said

of Lord Salisbury's acceptance of the Arbitration Treaty that it was

"one of the worst acts of what I regard as a very stupid and worthless

life." The British phrase 'Bob's your uncle' is thought to have derived from Robert Cecil's appointment of his nephew, Arthur Balfour, as Minister for Ireland .