<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Lipót Fejér, 1880

- Composer Alban Maria Johannes Berg, 1885

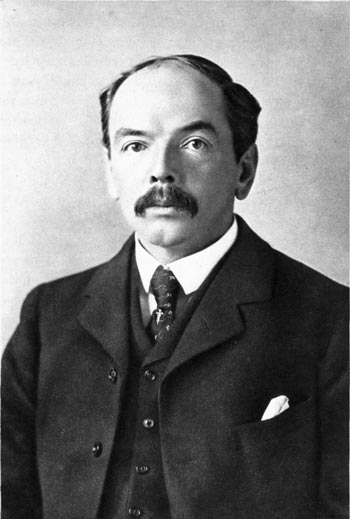

- Prime Minister of the Cape Colony Leander Starr Jameson, 1853

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, KCMG, CB, (February 9, 1853 – November 26, 1917), also known as "Doctor Jim", "The Doctor" or "Lanner", was a British colonial statesman who was best known for his involvement in the Jameson Raid.

He was born on 9 February 1853, of the Jameson family of Edinburgh, Scotland, the son of Robert William Jameson (1805 – 1868), a Writer to the Signet, and Christian Pringle, daughter of Major General Pringle of Symington. Robert William and Christian Jameson had twelve children, of whom Leander Starr was the youngest, born at Stranraer, Galloway, in the south-west of Scotland, great-nephew of Professor Robert Jameson, Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh. Fort's biography of Jameson notes that Starr's '...chief Gamaliel, however, was a Professor Grant, a man of advanced age, who had been a pupil of his great-uncle, the Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh.'

Leander Starr Jameson's somewhat unusual name resulted from the fact that his father Robert William Jameson had been rescued from drowning on the morning of his birth by an American traveller, who fished him out of a canal or river with steep banks into which William had fallen while on a walk awaiting the birth of his son. The kindly stranger named "Leander Starr" was promptly made a godfather of the baby, who was named after him. His father, Robert William, started his career as an advocate in Edinburgh, and was Writer to the Signet, before becoming a playwright, published poet and editor of the Wigtownshire Free Press.

A radical and reformist, Robert William Jameson was the author of the dramatic poem Nimrod (1848) and Timoleon, a tragedy in five acts informed by the anti-slavery movement. Timoleon was performed at the Adelphi Theatre in Edinburgh in 1852, and ran to a second edition. In due course, the Jameson family moved to London, England, living in Chelsea and Kensington. Leander Starr Jameson went to the Godolphin School in Hammersmith, where he did well in both lessons and games prior to his university education.

L.S. Jameson was educated for the medical profession at University College Hospital, London, for which he passed his entrance examinations in January, 1870. He distinguished himself as a medical student, becoming a Gold Medallist in materia medica. After qualifying as a doctor, he was made Resident Medical Officer at University College Hospital (M.R.C.S. 1875; M.D. 1877).

After acting as house physician, house surgeon and demonstrator of anatomy, and showing promise of a successful professional career in London, his health broke down from overwork in 1878, and he went out to South Africa and settled down in practice at Kimberley. There he rapidly acquired a great reputation as a medical man, and, besides numbering President Kruger and the Matabele chief Lobengula among his patients, came much into contact with Cecil Rhodes.

Jameson

was for some time the inDuna of the Matabele king's favourite regiment,

the Imbeza. Lobengula expressed his delight with Jameson's successful

medical treatment of his gout by honouring him with the rare status of inDuna. Although Jameson was a white man, he underwent the initiation ceremonies linked with this honour. Jameson's

status as an inDuna gave him advantages, and in 1888 he successfully

exerted his influence with Lobengula to induce the chieftain to grant

the concessions to the agents of Rhodes which led to the formation of

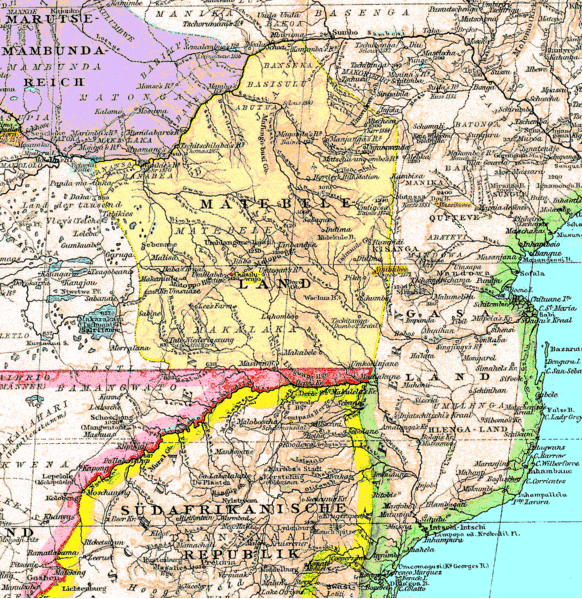

the British South Africa Company; and when the company proceeded to open up Mashonaland,

Jameson abandoned his medical practice and joined the pioneer

expedition of 1890. From this time his fortunes were bound up with

Rhodes' schemes in the north. Immediately after the pioneer column had

occupied Mashonaland, Jameson, with F.C. Selous and A.R. Colquhoun, went east to Manicaland and was instrumental in securing the greater part of the country, to which Portugal was laying claim, for the Chartered Company. In 1891 Jameson succeeded Colquhoun as Administrator of Mashonaland. In 1893, Jameson was a key figure in the First Matabele War and involved in incidents that led to the massacre of the Shangani Patrol. Jameson's character seems to have inspired a degree of devotion from his contemporaries. Elizabeth Longford

writes

of him, "Whatever one felt about him or his projects when he was not

there, one could not help falling for the man in his presence....

People attached themselves to Jameson with extraordinary fervour, the

more extraordinary because he made no effort to feed it. He affected an

attitude of tough cynicism towards life, literature and any articulate

form of idealism, particularly towards the hero-worship which he

himself excited ... When he died The Times estimated that his astonishing personal hold over his followers had been equalled only by that of Parnell, the Irish patriot." Longford also notes that Rudyard Kipling wrote the poem 'If'

with Leander Starr Jameson in mind as an inspiration for the

characteristics he recommended young people to live by (notably

Kipling's son, to whom the poem is addressed in the last lines).

Longford writes, "Jameson was later to be the inspiration and hero of

Rudyard Kipling's poem, 'If'...". Direct evidence that the poem 'If'

was written about Jameson is available also in Rudyard Kipling's

autobiography in which Kipling writes that "If--" was "drawn from

Jameson's character." As

reported below, in 1895, Jameson led about 500 of his countrymen in

what became known as The Jameson Raid against the Boers in southern

Africa. The Jameson Raid was later cited by Winston Churchill as a

major factor in bringing about the Boer War of 1899 to 1902. But the

story as recounted in Britain was quite different. The British defeat

was interpreted as a victory and Jameson was portrayed as a daring

hero. The poem celebrates heroism, dignity, stoicism and courage in the

face of the disaster of the failed Jameson Raid, for which he was

wrongfully made a scapegoat. Jameson's

persuasive character, what became known later as 'the Jameson charm',

was described in some detail by G.Seymour Fort (1918), who writes of

his restless, logical and sagacious temperament in this way: "...

It was not his wont to talk at length, nor was he, unless exceptionally

interested, a good listener. He was so logical and so quick to grasp a

situation, that he would often cut short exposition by some forcible

remark or personal raillery that would all too often quite disconcert

the speaker. Despite

his adventurous career, mere reminiscences obviously bored him; he was

always for movement, for some betterment of present or future

conditions, and in discussion he was a master of the art of persuasion,

unconsciously creating in those around him a latent desire to follow,

if he would lead. The source of such persuasive influence eludes

analysis, and, like the mystery of leadership, is probably more psychic

than mental. In this latter respect, Jameson was splendidly equipped;

he had greater power of concentration, of logical reasoning, and of

rapid diagnosis, while on his lighter side he was brilliant in repartee

and in the exercise of a badinage that was both cynical and personal... ....

He wrapped himself in cynicism as with a cloak, not only to protect

himself against his own quick human sympathy, but to conceal the

austere standard of duty and honour that he always set to himself. He

was ever trying to hide from his friends his real attitude towards

life, and the high estimate he placed upon accepted ethical values...

He was essentially a patriot who sought for himself neither wealth, nor

power, nor fame, nor leisure, nor even an easy anchorage for

reflection. The wide sphere of his work and achievements, and the

accepted dominion of his personality and his influence were both based

upon his adherence to the principle of always subordinating personal

considerations to the work in hand, upon the loyalty of his service to

big ideals. His whole life seems to illustrate the truth of the saying

that in self-regard and self-centredness there is no profit, and that

only in sacrificing himself for impersonal aims can a man save his soul

and benefit his fellow men." In November 1895, a piece of territory of strategic importance, the Pitsani Strip, part of the Bechuanaland Protectorate and bordering the Transvaal, was ceded to the British South Africa Company by the Colonial Office, overtly for the protection of a railway running through the territory. Cecil Rhodes, the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and managing director of the Company was eager to bring South Africa under British dominion, and encouraged the disenfranchised Uitlanders of the Boer republics to resist Afrikaner domination. Rhodes

hoped that the intervention of the Company's private army could spark

an Uitlander uprising, leading to the overthrow of the Transvaal

government. Rhodes' forces were assembled in the Pitsani Strip for this

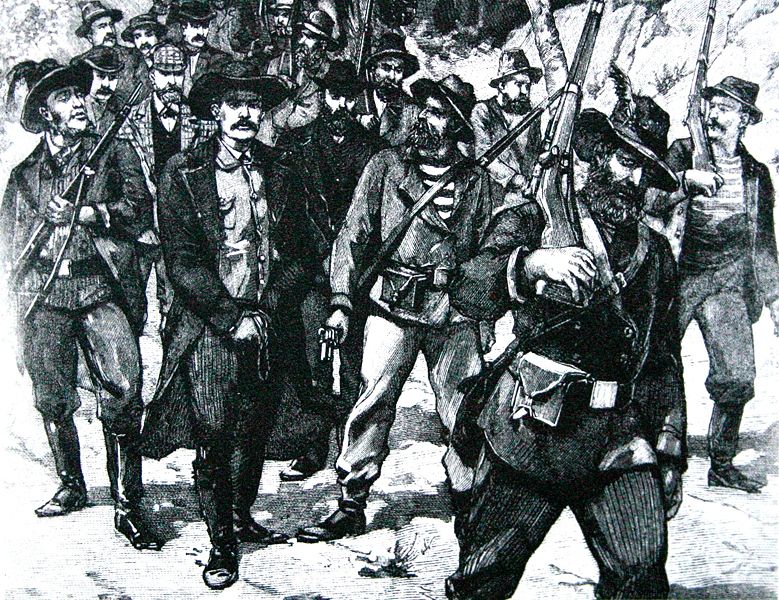

purpose. Joseph Chamberlain informed Salisbury on Boxing Day that an uprising was expected, and was aware that an invasion would be launched, but was not sure when. The subsequent Jameson Raid was a debacle, leading to the invading force's surrender. Chamberlain, at Highbury, received a secret telegram from the Colonial Office on 31 December informing him of the beginning of the Raid. In 1895, Jameson assembled a private army outside the Transvaal in preparation for the violent overthrow of the Boer government. The idea was to foment unrest among foreign workers (Uitlanders)

in the territory, and use the outbreak of open revolt as an excuse to

invade and annex the territory. Growing impatient, Jameson launched the

Jameson Raid in December 1895, and managed to push within twenty miles

of Johannesburg before superior Boer forces compelled him and his men to surrender. Sympathetic

to the ultimate goals of the Raid, Chamberlain was uncomfortable with

the timing of the invasion and remarked that "if this succeeds it will

ruin me. I'm going up to London to crush it". He swiftly travelled by

train to the Colonial Office, ordering Sir Hercules Robinson,

Governor-General of the Cape Colony, to repudiate the actions of

Jameson and warned Rhodes that the Company's Charter would be in danger

if it were discovered that the Cape Prime Minister was involved in the

Raid. The prisoners were returned to London for trial, and the

Transvaal government received considerable compensation from the

Company. Jameson was tried in England for leading the raid; during that time he was lionized by the press and London society. The

Jameson Raiders arrived in England at the end of February, 1896 to face

trial. There were some months of investigations initially held at Bow

Street, following which the 'trial at bar' (a legal procedure reserved

only for very important cases) began on June 20, 1896, at the High

Court of Judicature. The trial lasted seven days, following which Dr

Jameson was 'found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment as a

first-class misdemeanant for fifteen months. He was, however, released

from Holloway in the following Dec on account of illness.' During

the trial of Jameson, Rhodes' solicitor, Bourchier Hawksley, refused to

produce cablegrams that had passed between Rhodes and his agents in

London during November and December 1895. According to Hawksley, these

demonstrated that the Colonial Office 'influenced the actions of those

in South Africa' who embarked on the Raid, and even that Chamberlain

had transferred control of the Pitsani Strip to facilitate an invasion.

Nine days before the Raid, Chamberlain had asked his Assistant

Under-Secretary to encourage Rhodes to 'Hurry Up' because of the

deteriorating Venezuelan situation. Jameson

was sentenced to fifteen months in jail, but was soon pardoned. In June

1896, Chamberlain offered his resignation to Salisbury, having shown

the Prime Minister one or more of the cablegrams implicating him in the

Raid's planning. Salisbury refused to accept the offer, possibly

reluctant to lose the government's most popular figure. Salisbury

reacted aggressively in support of Chamberlain, supporting the Colonial

Secretary's threat to withdraw the Company's charter if the cablegrams

were revealed. Accordingly, Rhodes refused to reveal the cablegrams,

and as no evidence was produced showing that Chamberlain was complicit

in the Raid's planning, the Select Committee appointed to investigate

the events surrounding the Raid had no choice but to absolve

Chamberlain of all responsibility. Jameson

had been Administrator General for Matabeleland at the time of the Raid

and his intrusion into Transvaal depleted Matabeleland of many of its

troops and left the whole territory vulnerable. Seizing on this

weakness, and a discontent with the British South Africa Company, the Matabele revolted in March 1896 in what is now celebrated in Zimbabwe as the First War of Independence – the Second Matabele War.

Hundreds of white settlers were killed within the first few weeks and

many more would die over the next year and a half at the hands of both

the Matabele and the Shona. With few troops to support them, the

settlers had to quickly build a laager in the centre of Bulawayo on

their own. Against over 50,000 Matabele held up in their stronghold of

the Matobo Hills as the settlers mounted patrols under such legendary

figures as Burnham, Baden-Powell, and Selous. After the Matabele laid down their arms, the war continued until October 1897 in Mashonaland. Despite

the Raid, Jameson had a successful political life following the

invasion, receiving many honours in later life. In 1903 Jameson came

forward as the leader of the Progressive (British) party in the Cape

Colony. When the party was successful he became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1904 to 1908. He served as the leader of the Unionist Party (South Africa) from its founding in 1910 until 1912. Jameson was created a baronet in 1911 and returned to England in 1912. According to Rudyard Kipling, his famous poem "If— "

was written in celebration of Leander Starr Jameson's personal

qualities at overcoming the difficulties of the Raid, for which he

largely took the blame, though Joseph Chamberlain,

British colonial secretary of the day, was, according to some

historians, implicated in the events of the raid. Jameson is buried at

Malindidzimu Hill l or World's View, a granite hill in the Matobo National Park 40 km south of Bulawayo. It was designated by Cecil Rhodes as the resting place for those who served Great Britain well in Africa. Rhodes is also buried there. Jameson

died in the afternoon of Monday, November 26, 1917 in the City of

London. His body was laid in a vault at Kensal Green Cemetery on 29

November, 1917, where it remained until the end of the First World War. Ian

Colvin (1923) writes that Jameson's body was then: "...carried

to Rhodesia and on May 22, 1920, laid in a grave cut in the granite on

the top of the mountain which Rhodes had called The View of the World,

close beside the grave of his friend. 'Thy firmness makes my circle

just, And makes me end where I begun.' There on the summit those two lie together." To this day, the events surrounding Jameson's involvement in the Jameson Raid,

being in general somewhat out of character with his prior history, the

rest of his life and successful later political career, remain

something of an enigma to historians. In 2002, The Van Riebeck Society

published Sir Graham Bower’s Secret History of the Jameson Raid and the South African Crisis, 1895-1902,

adding to growing historical evidence that the imprisonment and

judgement upon the Raiders at the time of their trial was an

underhanded move by the British government, a result of political

manoeuvres by Joseph Chamberlain and his staff to hide his own involvement and knowledge of the Raid. In his review of Sir Graham Bower’s Secret History ...Alan Cousins, notes

that, 'A number of major themes and concerns emerge' from Bower's

history, '... perhaps the most poignant being Bower’s accounts of his

being made a scapegoat in the aftermath of the raid: "since a scapegoat

was wanted I was willing to serve my country in that capacity".' Cousins

notes of Bower that 'a very clear sense of his rigid code of honour is

plain, and a conviction that not only unity, peace and happiness in South Africa,

but also the peace of Europe would be endangered if he told the truth.

He believed that, as he had given Rhodes his word not to divulge

certain private conversations, he had to abide by that, while at the

same time he was convinced that it would be very damaging to Britain if

he said anything to the parliamentary committee to show the close

involvement of Sir Hercules Robinson and Joseph Chamberlain in their

disreputable encouragement of those plotting an uprising in Johannesburg.'

Finally,

Cousins observes that, '...in his reflections, Bower has a particularly

damning judgement on Chamberlain, whom he accuses of ‘brazen lying’ to

parliament, and of what amounted to forgery in the documents made

public for the inquiry. In the report of the committee, Bower was found

culpable of complicity, while no blame was attached to Chamberlain or

Robinson. His name was never cleared during his lifetime, and Bower was

never reinstated to what he believed should be his proper position in

the colonial service: he was, in effect, demoted to the post of

colonial secretary in Mauritius. The bitterness and sense of betrayal he felt come through very clearly in his comments.' Speculation on the true nature of the behind-the-scenes story of the Jameson Raid has therefore continued for more than a hundred years after the events, and carries on to this day.