<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Jacques Herbrand, 1908

- Painter Max Beckmann, 1884

- Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, 1768

PAGE SPONSOR

Max Beckmann (February 12, 1884 – December 28, 1950) was a German painter, draftsman, printmaker, sculptor, and writer. Although he is classified as an Expressionist artist, he rejected both the term and the movement. In the 1920s, he was associated with the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), an outgrowth of Expressionism that opposed its introverted emotionalism.

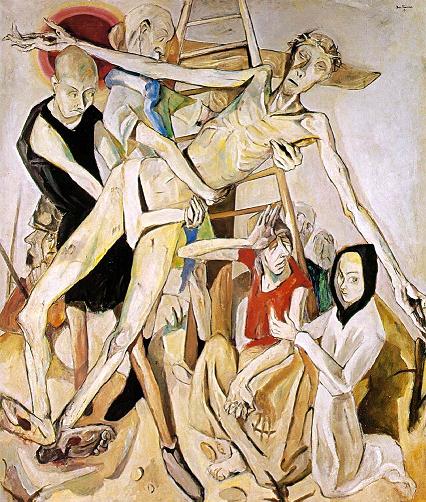

Max Beckmann was born into a middle-class family in Leipzig, Saxony. From his youth he pitted himself against the old masters. His traumatic experiences of World War I, in which he served as a medic, coincided with a dramatic transformation of his style from academically correct depictions to a distortion of both figure and space, reflecting his altered vision of himself and humanity.

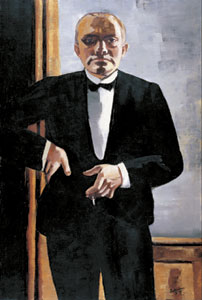

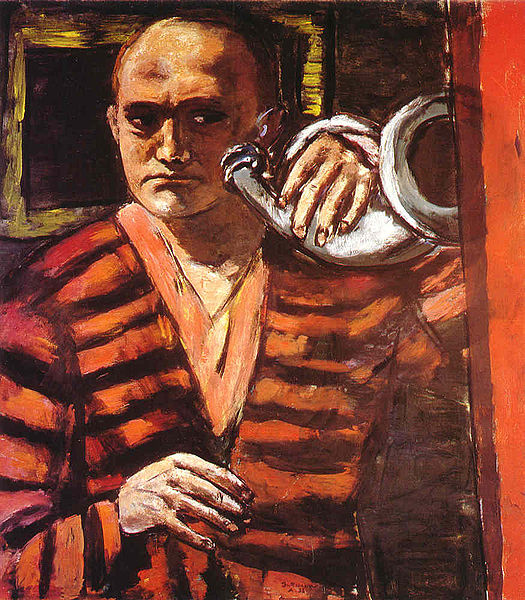

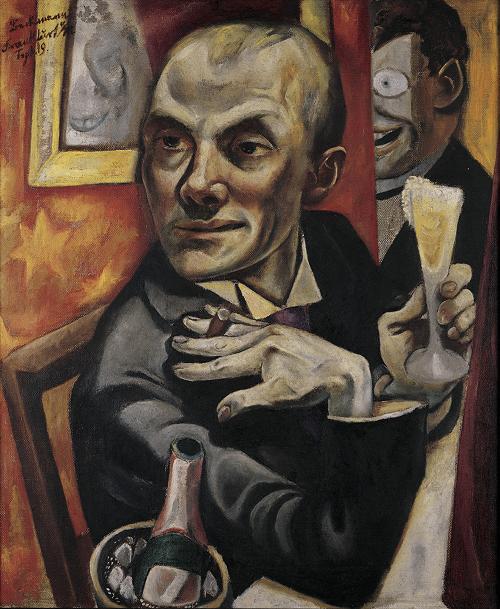

He is known for the self-portraits painted throughout his life, their number and intensity rivalled only by Rembrandt and Picasso. Well-read in philosophy and literature, he also contemplated mysticism and theosophy in search of the "Self". As a true painter-thinker, he strove to find the hidden spiritual dimension in his subjects. (Beckmann's 1948 "Letters to a Woman Painter" provides a statement of his approach to art.)

In the Weimar Republic of the Thirties, Beckmann enjoyed great success and official honors. In 1927 he received the Honorary Empire Prize for German Art and the Gold Medal of the City of Düsseldorf; the National Gallery in Berlin acquired his painting The Bark and, in 1928, purchased his Self-Portrait in Tuxedo. In 1925 he was selected to teach a master class at the Städelschule Academy of Fine Art in Frankfurt. Some of his most famous students included Theo Garve, Leo Maillet and Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky.

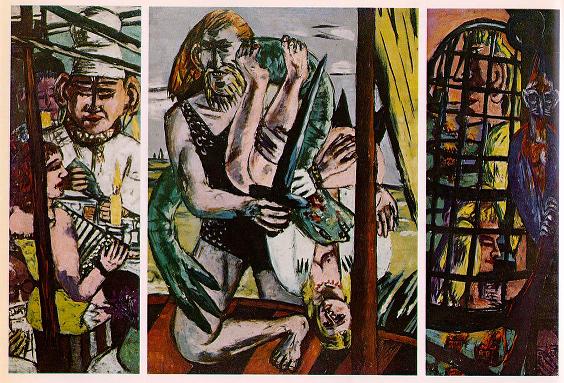

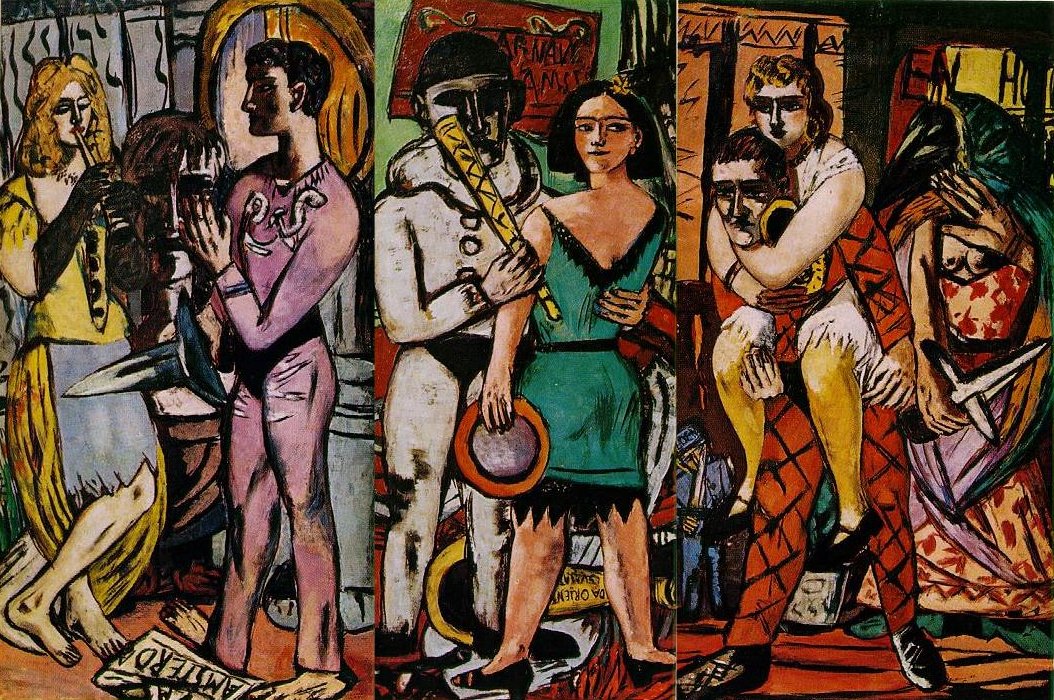

His fortunes changed with the rise to power of Adolf Hitler, whose dislike of Modern Art quickly led to its suppression by the state. In 1933, the Nazi government bizarrely called Beckmann a "cultural Bolshevik" and dismissed him from his teaching position at the Art School in Frankfurt. In 1937 more than 500 of his works were confiscated from German museums, and several of these works were put on display in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. For ten years, Beckmann lived in poverty in self-imposed exile in Amsterdam, failing in his desperate attempts to obtain a visa for the US. In 1944 the Germans attempted to draft him into the army, despite the fact that the sixty-year-old artist had suffered a heart attack. The works completed in his Amsterdam studio were even more powerful and intense than the ones of his master years in Frankfurt, and included several large triptychs, which stand as a summation of Beckmann's art.

After the war, Beckmann moved to the United States, and during the last three years of his life, he taught at the art schools of Washington University in St. Louis (with the German-American painter and printmaker Werner Drewes) and the Brooklyn Museum. He suffered from angina pectoris and died after Christmas 1950, struck down by a heart attack in Manhattan.

Many

of his late paintings are displayed in American museums. Max Beckmann,

a native of the very heart of Germany, exerted a profound influence on

such American painters as Philip Guston and Nathan Oliveira. Unlike several of his avant-garde contemporaries, Beckmann rejected non-representational painting; instead, he took up and advanced the tradition of figurative painting. He greatly admired Cézanne, but also Van Gogh, Blake, Rembrandt, Rubens and Northern European artists of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance such as Bosch, Bruegel and Matthias Grünewald. His style and method of composition are also rooted in the imagery of medieval stained glass. Encompassing

portraiture, landscape, still life, mythology and the fantastic, his

work created a very personal but authentic version of modernism, combining this with traditional plasticity. Beckmann reinvented the triptych and expanded this archetype of medieval painting into

a looking glass of contemporary humanity. On a more technical level

Beckmann proposes a version of abstraction in which the gestalt shift

form figural to abstract form is never complete. The eye is in a

condition of uncertainty and remains forever frozen in that condition.

Thus one might say the Ovidian metamorphic element in Beckmann is in

fact the stable reality. From its beginnings in the fin de siècle up to its completion after World War II,

Beckmann's work reflects an era of radical changes in both art and

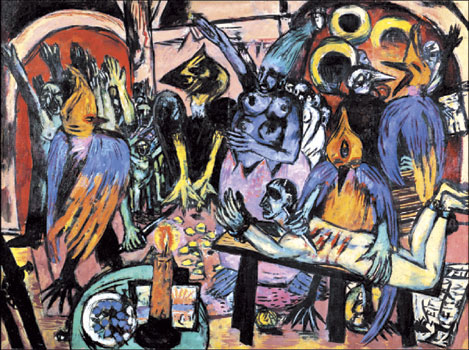

history. Many of Max Beckmann‘s paintings express the agonies of Europe

in the first half of the Twentieth Century. Some of his imagery refers

to the decadent glamor of the Weimar Republic's

cabaret culture, but from the Thirties on, his works often contain

mythologized references to the brutalities of the Nazis. Beyond these

immediate concerns, his subjects and symbols assume a larger meaning,

voicing universal themes of terror, redemption, and the mysteries of

eternity and fate. Beckmann's posthumous reputation perhaps suffered from his very individual artistic path; like Oskar Kokoschka,

he defies the convenient categorization that provides themes for

critics, art historians and curators. Other than a major retrospective

at New York's Museum of Modern Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago in

1964-65 (with an excellent catalogue by Peter Selz), and MoMA's

prominent display of the triptych "Departure", his work was little seen

in America for decades. His 1984 centenary was marked in the New York

area only by a modest exhibit at Nassau County's suburban art museum. Since

then, Beckmann's work has gained an increasing international

reputation. There have been retrospectives and exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (1995) and the Guggenheim Museum (1996) in New York, and the principal museums of Rome (1996), Valencia (1996), Madrid (1997), Zurich (1998), St. Louis — which

holds the largest public collection of Beckmann paintings in the

world — (1998), Munich (2000), Frankfurt (2006) and Amsterdam (2007). In

Spain and Italy, Beckmann's work has been accessible to a wider public

for the first time. A large-scale Beckmann retrospective was exhibited

at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (2002) and Tate Modern in London (2003). In

1996, Piper, Beckmann's German publisher, released the third and last

volume of the artist’s letters, whose wit and vision rank him among the

strongest writers of the German tongue. His essays, plays and, above

all, his diaries are also unique historical documents. A selection of

Beckmann's writings was issued in America in 1996. In 2003, Stephan Reimertz, Parisian novelist and art historian, published the biography of

Max Beckmann. It presents many photos and sources for the first time.

The biography reveals Beckmann's contemplations on writers and

philosophers such as Dostoyevsky, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Richard Wagner. The book has not yet been translated into English.