<Back to Index>

- Sociologist Robert Ezra Park, 1864

- Novelist Edmond François Valentin About, 1828

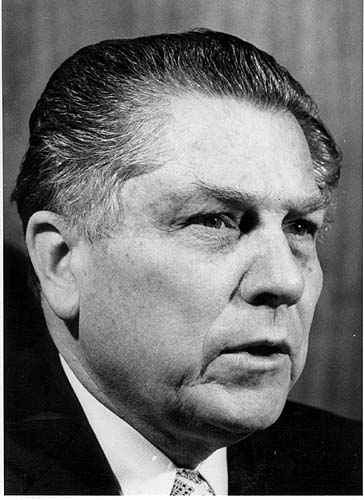

- Labor Union Leader James Riddle "Jimmy" Hoffa, 1913

PAGE SPONSOR

James Riddle "Jimmy" Hoffa (born February 14, 1913 – disappeared July 30, 1975, declared legally dead July 30, 1982) was an American trade union leader.

Hoffa was involved with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union, as an organizer from

1932 to 1975. He served as the union's General President from 1958 to

1971. He secured the first national agreement for teamsters' rates in

1964, and played a major role in the growth and development of the

union, which eventually became the largest single union in the United

States, with over 1.5 million members during his terms as its leader. Hoffa, who had been convicted of jury tampering, attempted bribery, and fraud in

1964, was imprisoned in 1967, sentenced to 13 years, after exhausting

the appeal process. However, he did not officially resign the

Teamsters' presidency until mid-1971. This was part of a pardon agreement with U.S. president Richard Nixon,

in order to facilitate Hoffa's release from prison in late 1971. Nixon

blocked Hoffa from union activities until 1980; Hoffa was attempting to

overturn this order and to regain support. He was last seen in late

July 1975, outside a suburban Detroit restaurant called the Machus Red Fox. Hoffa was born in Brazil, Indiana, on February 14, 1913. His paternal ancestors were "Pennsylvania Dutch" and German. Jimmy's father, a coal miner, died in 1920 when Jimmy was seven years old; the family moved to Detroit in

1924, where Hoffa was raised and lived the rest of his life. Hoffa left

school at age 14, and began full-time manual labor to help support his

family. Hoffa

began union organizational work at the grassroots level through his

employment as a teenager with a grocery chain, which paid substandard

wages and offered poor working conditions with minimal job security.

The workers were displeased with this situation, and tried to organize

a union to better their lot. Although Hoffa was young, his bravery and

approachability in this role impressed fellow workers, and he rose to a

leadership position. A while later, after being dismissed from the

grocery chain, in part because of his union activities, Hoffa became

involved with Local 299 of the Teamsters, in Detroit, by 1932, when he

joined that union. He married Josephine Poszywak in 1936, and bought a modest home in Detroit. The couple had two children: a daughter, Barbara Ann Crancer, and a son, James P. Hoffa. The Hoffa family later had a summer property at Lake Orion, Michigan, north of Detroit. The

Teamsters union was founded in 1899, but even as late as 1933, it had

only 75,000 members. Hoffa worked with other union leaders to

consolidate local union trucker groups into regional sections, and then

finally into one gigantic national body, over a period of two decades.

The Teamsters had 170,000 members in 1936, 420,000 in 1939, grew

steadily during World War II, and rode the post-war boom to top a million members by 1951. The Teamsters organized truckers and firefighters first throughout the Midwest, and then nationwide across the United States. The union skillfully used "quickie strikes", secondary boycotts, and other means of leveraging union strength

at one company, then moved to organize workers, and then win contract

demands at other companies. This process, which took several years from

the early 1930s, eventually brought the Teamsters to a position of

being one of the most powerful unions in the United States. Hoffa

played a major role in the growth of the Teamsters union. Although Hoffa never actually worked as a truck driver, he became president of Local 299 in December 1946. He

then rose to lead the combined group of Detroit area locals shortly

afterwards, and then advanced to become head of the Michigan Teamsters

groups sometime later. He obtained a deferment from military service in World War II,

by successfully making a case for his union leadership skills being of

more value to the nation, by keeping freight running smoothly to assist

the war effort. Hoffa worked to defend the Teamsters unions from raids

by other unions, including the CIO, and extended the Teamsters' influence in the Midwestern states, from the late 1930s to the late 1940s. By 1952, Hoffa rose to national vice-president of the Teamsters' IBT union,

which was on its way to becoming the largest and most powerful single

union in the United States. At the IBT convention in Los Angeles, he was selected by incoming president Dave Beck, who succeeded Daniel J. Tobin,

president since 1907. Hoffa quelled an internal revolt against Beck by

securing Central States region support for Beck at the convention; in

exchange, Beck made him a vice-president. The IBT moved its headquarters from Indianapolis to Washington, DC,

taking over a large office building in the U.S. capital in 1955. IBT

staff was also enlarged during this period, with many lawyers hired to

assist with contract negotiations. Following his 1952 election as

vice-president, Hoffa began spending more of his time away from

Detroit, either in Washington or traveling around the U.S. for his

expanded responsibilities. He also travelled to Israel in 1956, to meet with labor groups there.

Hoffa took over the presidency of the Teamsters in 1957, at the convention in Miami Beach, Florida. His predecessor, Dave Beck, had appeared before the John Little McClellan-led U.S. Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, in March 1957, and took the Fifth Amendment 140 times in response to questions. Beck was under indictment when the IBT convention took place, and was later in 1957 convicted on fraud charges, at a trial held in Seattle, and imprisoned.

The 1957 AFL-CIO convention, held in Atlantic City, New Jersey, voted by a ratio of nearly 5-1 to expel the IBT from the larger union group. President George Meany gave

an emotional speech, advocating removal of the IBT, and stating that he

could only agree to further affiliation of the Teamsters if they would

dismiss Hoffa as their president. Meany demanded a response from Hoffa,

who replied through the press, "We'll see." At the time, IBT was

bringing in over $750,000 annually to the AFL-CIO. Hoffa

was re-elected as president in 1961. Hoffa worked to expand the union,

and, in 1964, succeeded in bringing virtually all over-the-road truck

drivers in North America under a single national master-freight agreement. This may have been his finest achievement in a lifetime of union activity. Hoffa then tried to bring the airline workers

and other transport employees into the union, with limited success. He

was facing immense personal strain, since he was under investigation,

on trial, launching appeals of convictions, or imprisoned for virtually

all of the 1960s. Hoffa's son, James P. Hoffa, is the Teamsters' current leader, serving since 1999 in that position. His daughter, Barbara Ann Crancer, currently serves as an associate circuit court judge in St. Louis, Missouri. In 1964, Hoffa was convicted in Chattanooga, Tennessee of attempted bribery of a grand juror, and was sentenced to eight years. This case had resulted from an earlier matter, the Test Fleet case, which had been held in Nashville, Tennessee. Hoffa was implicated by one of his close associates, Edward Grady Partin, a Louisiana teamster, who went to the Federal Bureau of Investigation with devastating information, which led to Hoffa's conviction. Hoffa was also convicted of fraud later in 1964, for improper use of the Teamsters' pension fund, in a trial held in Chicago. Hoffa received a five-year sentence for that offense, to run consecutively to his bribery sentence. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who had pursued Hoffa for years, since the John Little McClellan-led

U.S. Senate Labor industry hearings of 1957, stepped down as Attorney

General after the second Hoffa conviction, in mid-1964, to run

successfully in November 1964 as a Democrat for the United States Senate from New York state, having unseated the liberal Republican Kenneth B. Keating. Hoffa

spent the next three years unsuccessfully appealing his 1964

convictions. He began serving his sentences in March, 1967 at the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in Pennsylvania. Just before he entered prison, Hoffa appointed Frank Fitzsimmons as

acting Teamsters president; Fitzsimmons was a Hoffa loyalist, fellow

Detroit resident, and a longtime member (since the 1930s) of Teamsters

Local 299 in Detroit, who owed his own high position in large part to

Hoffa's influence. Fitzsimmons

distanced himself from Hoffa's influence and control after 1967, to

Hoffa's displeasure. Fitzsimmons also decentralized power somewhat

within the Teamsters' union administration structure; during the Hoffa

era, Hoffa had kept most power in his own hands. On December 23, 1971, however, Hoffa was released from the Lewisburg, Pennsylvania prison, when President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence to time served; Hoffa had served nearly 58 months, or just

over one-third of his original sentence. However, the president imposed

the condition that Hoffa not participate in union activities until

1980. Hoffa, while glad to regain his freedom, had not sought the

non-participation conditions, and was unhappy with this situation. Hoffa accused Nixon administration senior figures, including Attorney General John N. Mitchell and White House Counsel Charles W. Colson,

of depriving him of his rights by initiating this clause; both Mitchell

and Colson denied this. But it was likely imposed upon Hoffa as the

result of requests from senior Teamsters' leadership, although IBT

President Frank Fitzsimmons also denied this.

Hoffa

was planning to sue to invalidate that non-participation restriction,

in order to reassert his power over the Teamsters. He faced immense

resistance to his plan, from many quarters, and had lost most of his

earlier support, even in the Detroit area. Hoffa was planning to begin

his comeback at the local level, with Local 299 in Detroit, where he

retained some influence. Following

his release from prison, Hoffa was awarded a Teamsters' pension of $1.7

million, delivered in a one-time lump sum payment. This type of pension

settlement had not occurred before with the Teamsters. Hoffa was working on an autobiography in 1975. The book, titled Hoffa: The Real Story, was published a few months after his disappearance. He had earlier published a 1970 book titled The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa. An interview with Hoffa appeared in Playboy magazine, December 1975 issue, several months after his disappearance. Hoffa disappeared at, or sometime after, 2:45 pm on July 30, 1975, from the parking lot of the Machus Red Fox Restaurant in Bloomfield Township, Oakland County, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit. According to what he had told others, he had believed he was to meet there with two Mafia leaders, Anthony Giacolone from Detroit and Anthony Provenzano from Union City, New Jersey and New York City. Provenzano

was also a union leader with the Teamsters in New Jersey, who had

earlier been quite close to Hoffa. Provenzano was a national

vice-president with IBT from 1961, Hoffa's second term as Teamsters'

president. Upon

Hoffa's failure to return home from the restaurant by late that

evening, his wife called police to report him missing. When police

arrived at the restaurant, they found Hoffa's car, but no sign of Hoffa

himself, nor any indication of what had happened to him. Extensive

investigations into the disappearance began immediately, and continued

over the next several years, by several law enforcement groups,

including the FBI.

However, the investigations failed to conclusively determine Hoffa's

fate. For their part, Giacolone and Provenzano were each found not to

have been in the vicinity of the restaurant that afternoon, and each of

them denied that they had scheduled any meeting with Hoffa. Hoffa was declared legally dead in 1982, on the seventh anniversary of his disappearance. On May 17, 2006, acting on a tip, the FBI searched a farm in Milford Township, Michigan, for Hoffa's remains. Nothing was found. On June 16, 2006, the Detroit Free Press published

in its entirety the so-called Hoffex Memo, a 56-page report the FBI

prepared for a January 1976 briefing on the case at FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C..

Although not claiming to conclusively establish the specifics of his

disappearance, the memo indicates that law enforcement's belief is that

Hoffa was murdered at the behest of organized crime figures who deemed

his efforts to regain power within the Teamsters to be a threat to

their control of the union's pension fund. The FBI has called the report the definitive account of what agents believe happened to Hoffa.