<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Tobias Mayer, 1723

- Architect Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, 1699

- President of Ecuador Galo Plaza Lasso, 1906

PAGE SPONSOR

Hans Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff (17 February 1699 – 16 September 1753) was a painter and architect in Prussia.

Knobelsdorff was born in Kuckädel, now in Krosno Odrzańskie County. A soldier in the service of Prussia, he resigned his commission in 1729 as captain so

that he could pursue his interest in architecture. In 1740 he travelled

to Paris and Italy to study at the expense of the new king, Frederick II of Prussia. Knobelsdorff was influenced as an architect by French Baroque Classicism and by Palladian architecture. With his interior design and the backing of the king, he created the basis for the Frederician Rococo style at Rheinsberg, which was the residence of the crown prince and later monarch. Knobelsdorff

was the head custodian of royal buildings and head of a privy council

on financial matters. In 1746 he was fired by the king, and Johann Boumann finished all his projects, including Sanssouci. Knobelsdorff died in Berlin. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof I der Jerusalems - und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. I of the congregations of Jerusalem's Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor. Karl Begas the younger created a statue of Knobelsdorff in 1886. This originally stood in the entrance hall of the Altes Museum (in Berlin) and is now in a depot of the state museum. Georg

Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, the son of Silesian landed gentry, was

born on February 17, 1699 on the estate of Kuckädel (now Polish

Kukadlo) near Crossen (now the Polish city Krosno Odrzańskie) on the

Oder River. After the early death of his father he was raised by his

godfather, the chief senior forester Georg von Knobelsdorff. In keeping

with family tradition he began his professional career in the Prussian

army. Already at 16 years of age he participated in a campaign against

King Charles XII of Sweden, and in 1795 in the siege of Stralsund. While

still a soldier he developed his artistic talents in self-study. After

leaving military service he arranged to be trained in various painting techniques by the Prussian court painter Antoine Pesne, with whom he shared a lifelong friendship. Knobelsdorff also acquired additional expertise in geometry and anatomy.

He saw his professional future in painting, and his pictures and

drawings were always highly appreciated, even after the focus of his

activities turned elsewhere. His

interest in architecture developed in a roundabout way, and came from

representing buildings in his pictures. Later, the pictorial aspect of

his architectural sketches was often noted and met with varying

reactions. Heinrich Ludwig Manger, as an architect more a technician

than an artist, wrote with a critical undertone in 1789 in his Baugeschichte von Potsdam,

that Knobelsdorff designed his buildings “merely in a perspective and

picturesque way”, but praised his paintings. Frederick the Great, in

contrast, commented positively on the architect’s “picturesque style” (gout pittoresque).

There is also no evidence that the informal style of his drawings ever

posed a serious impediment to the execution of his buildings. Knobelsdorff

acquired the expertise needed for his new profession again primarily in

self-study, after a brief period of training under the architects

Kemmeter and von Wangenheim. This breed of “gentlemen architects” was

not unusual in the 16th and 17th centuries, and they were esteemed both

socially and because of their specialized competence. They trained

themselves by studying actual buildings on extensive travels as well as

collections of engravings showing views of classical and contemporary

buildings. Knobelsdorff’s ideal models, the Englishmen Inigo Jones (1573 – 1652) and William Kent (1684 – 1748)

as well as the Frenchman Claude Perrault (1613 – 1688), likewise grew

into their professions in a roundabout way and were no longer young men

when they turned to architecture. Knobelsdorff gained the attention of King Frederick William I of Prussia (the

"Soldier-King"), who had him join the entourage of his son, crown

prince Frederick, later King Frederick II (Frederick the Great). After

his failed attempt to flee Prussia and subsequent imprisonment in

Küstrin, (now Polish Kostrzyn nad Odrą),

Frederick had just been granted somewhat more freedom of movement by

his strict father. Apparently, the king hoped that Knobelsdorff, as a

sensible and artistically talented nobleman, would have a moderating

influence on his son. (The sources vary as to what prompted the first

meeting between Knobelsdorff and Frederick, but they all date the event

as being in 1732.) At the time the crown prince, who had been appointed a colonel when he turned 20, took over responsibility for a regiment in the garrison town of Neuruppin.

Knobelsdorf became his partner in discussions and advised him on issues

of art and architecture. Immediately in front of the city walls they

jointly planned the Amalthea garden,

which contained a monopteros, a little Apollo temple of classical

design. This was the first construction of its type on the European

continent and Knobelsdorff’s first creation as Frederick the Great’s

architect. This was where they made music, philosophized, and celebrated, and also after the crown prince had moved to nearby Rheinsberg Castle he frequently visited the temple garden during visits connected with his duties as commander in the Neuruppin garnison. In

1736 the crown prince gave Knobelsdorff an opportunity to go on a study

tour to Italy, which lasted until spring 1737. His stops included Rome, Naples and vicinity, Florence and Venice.

He recorded his impressions in a travel sketchbook which contains

almost one hundred pencil drawings, but only of part of his trip since

on the return stretch he broke his arm in a traffic accident between

Rome and Florence. He was unable to carry out a secret mission which

involved engaging Italian opera singers to come to Rheinsburg since the

available funds were inadequate. Knobelsdorff wrote to the crown prince

that “The castrati here

cannot be tempted to leave [...] regular employment, especially for

those from the poorer classes, is the reason why they prefer 100 Rthlr (Reichstaler) in Rome to thousands abroad. In autumn 1740, shortly after Frederick assumed the throne, Knobelsdorff was sent on another study tour. In Paris only the work of the architect Perrault impressed him — the frontage of the Louvre and the garden side of the castle in Versailles. As to paintings, he listed those of Watteau, Poussin, Chardin and others. On the return trip via Flanders he saw paintings by van Dyck and Rubens. Rheinsberg

Palace and the modest household of the crown prince became a place of

relaxed communion and artistic creativity, quite in contrast to the

dry, matter-of-fact atmosphere at the Berlin court of the soldier-king.

This was where Frederick and Knobelsdorff discussed architecture and city planning,

and developed their first ideas for an extensive program of

construction which was to be realized when the crown prince assumed the

throne. Rheinsberg was where Knobelsdorff received his first major

architectural challenge. At that time the palace consisted only of a

tower and a building wing. In a painting from 1737 Knobelsdorff

depicted the situation before the alterations, as viewed from the far

shore of Lake Grienericksee. After preliminary work by the architect

and builder Kemmeter and in regular consultation with Frederick,

Kobelsdorff gave the ensemble its present form. He extended the grounds

by a second tower and matching building wing and by a colonnade

connecting both towers. As

a significant construction, this design was planned already in

Rheinsberg as a signal for the start of Frederick’s reign. In Berlin the

king wanted to have a new city palace that could stand up to the

splendid residences of major European powers. Knobelsdorff designed an

extensive building complex with inner courtyards and in front a cour d'honneur and semicircular colonnades just north of the street Unter den Linden.

In front of that he planned a spacious square with two free-standing

buildings — an opera house and a hall for ball games. Soon after

Frederick acceded to the throne in May 1740, foundation testing began,

as well as negotiations about the purchase and demolition of 54 houses

that interfered with the project. Already on August 19, 1740 all these

preparations were discontinued, supposedly because the intended ground

was unsuitable. But in fact the king’s distant relatives refused to

sell their palaces, which were located in the middle of the planned

square. Frederick attempted to rescue the situation and sketched in modifications on the plan of the layout. When the First Silesian War (1740 - 1742)

began, decisions about the Forum had to be postponed. However, even

while the war was being waged the king wanted Knobelsdorff to begin

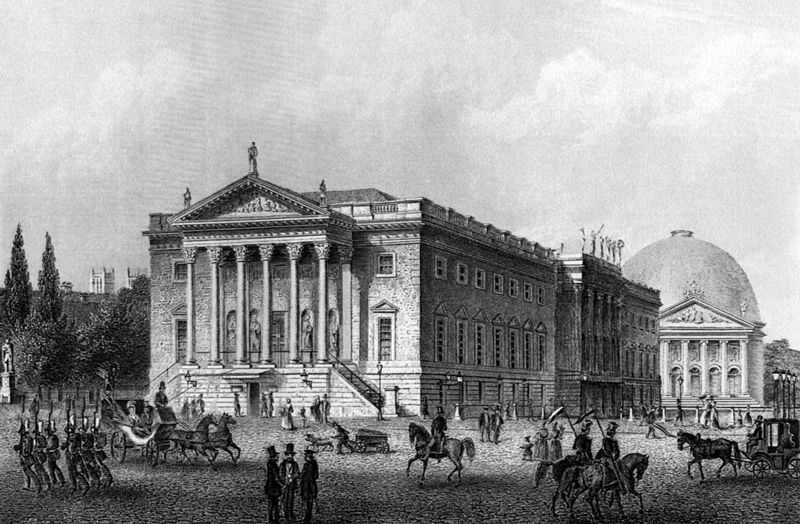

construction of the opera house, today’s Berlin State Opera (Staatsoper Unter den Linden).

Work languished on the Forum also after the end of the war. Beginning

of 1745 Frederick’s increasing interest in Potsdam as a second

residence became evident and the original plans moved into the

background. Construction on the square with the opera house (Opernplatz, today’s Bebelplatz) moved in another direction. In 1747 work began on St. Hedwig’s Cathedral,

in 1748 on the Prince Heinrich Palace, and between 1775 and 1786 the

Royal Library was erected. The final square bore little resemblance to

the original plan, but was highly praised already by contemporaries and

also in this form caused the royal architect to achieve great eminence.

The terms “Frederick’s Forum” and “Forum Fridericianum” only appeared

in specialist literature in the 19th century and were never officially

used to refer to the square.

Knobelsdorff

was involved in the construction of St. Hedwig’s Cathedral, but it is

uncertain to what extent. Frederick II presented the Catholic community

with complete building plans, which were probably primarily his ideas

which were then realized by Knobelsdorff. The opera house, by contrast,

was completely designed by Knobelsdorff and is considered to be one of

his most important works. For the frontage of the externally modestly

structured building the architect followed the model of two views from

Colin Campbell’s “Vitruvius Britannicus”, one of the most important collections of architectonic engravings, which included works of English Palladian architecture. For the interior he designed a series of three prominent rooms with

different functions, which were at different levels, and were decorated

differently: the Apollo Hall, the spectator viewing area, and the

stage. By technical means they could be turned into one large room for

major festivities. Knobelsdorff described the technical features in a

Berlin newspaper, proudly commenting that “this theater is one of the

longest and widest in the world”. In 1843 the building burned down to

the foundation. In World War II it suffered several times from bombing.

Each time the rebuilding followed Knobelsdorff’s intentions, but there

were also clear modifications of both the facing and the interior. Soon

after they were completed, the opera house and St. Hedwig’s Cathedral

were featured in textbooks and manuals on architecture. Already

in Neuruppin and Rheinsberg Knobelsdorff had designed together with the

crown prince gardens which followed a French style. On November 30,

1741, Frederick II, now king, issued a decree which initiated the

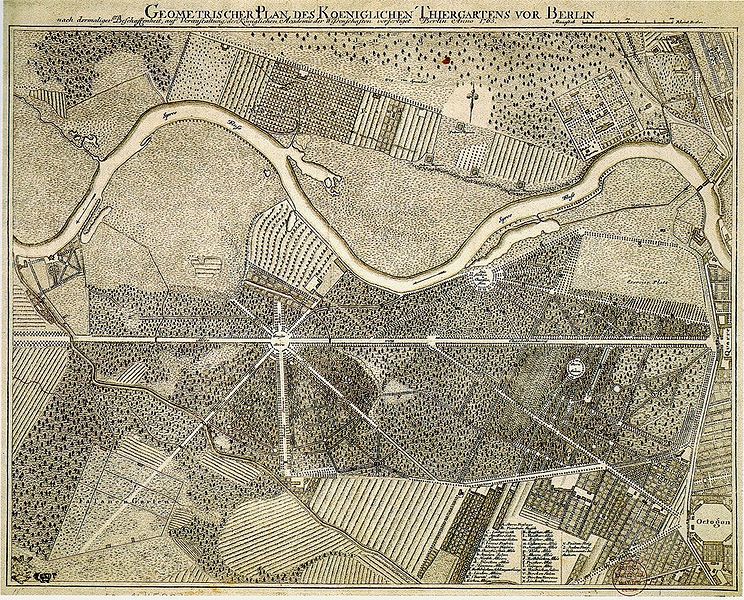

redesign of the Berlin Tiergarten to

make it the “Parc de Berlin”. The document pointed out that Baron

Knobelsdorff had received precise instructions concerning the

changeover. The Tiergarten, in times past the private hunting grounds

of the Electors and

greatly neglected under Frederick’s father, was to be turned into the

public park and gardens of the royal residence city of Berlin. In order to

protect the newly cultivated areas the practice of driving cattle on

the grounds was forbidden with immediate effect. Frederick’s interest

in this project can also be recognized in a later decree, which forbade

the removal of large bushes or trees without the specific permission of

the king. As a precondition to redesigning the Tiergarten,

large portions of the grounds had to be drained. In many cases

Knobelsdorff gave the necessary drainage ditches the form of natural

waterfalls, a solution which Friedrich II later praised. The actual

work began with the improvement of the main axis of the park, a path

which extended the boulevard Unter den Linden through the Tiergarten to Charlottenburg (now Strasse des 17. Juni. This road was lined with hedges, and the junction of eight avenues marked by the Berlin victory column (Siegessäule) was decorated with 16 statues. To the south Knobelsdorff arranged for three so-called labyrinths (these were actually mazes)

in the pattern of famous French parks — areas separated off with

artistically designed intertwined hedgerows. Especially in the eastern

part of the park near the Brandenburg Gate there

was a dense network of pathways which constantly intersected and

contained many “salons” and “cabinets” — small enclosed areas so to speak

“furnished” with benches and fountains. Knobelsdorff’s successor, the

court gardener Justus Ehrenreich Sello, began the modification of these

late Barock pleasure grounds in the style of the new ideal of an English landscape park.

Toward the end of the 18th century there was hardly anything left of

Knobelsdorff’s version except for the main features of the system of

paths. But the fact remains that he designed the first park in Germany open to the public from the very beginning. Beginning of 1746 Knobelsdorff purchased at a good price extensive grounds on the verge of the Tiergarten at an auction. It was situated between the victory column and the Spree River, about where today Bellevue Palace is

located. The property included a mulberry plantation, meadows and

farmland, vegetable beds and two dairys. Knobelsdorff had a new main

building erected, externally a plain garden house. The wall and ceiling

paintings in several rooms were considered to be a present from Antoine Pesne to

his student and friend. The building was demolished in 1938. A number

of biographers were of the opinion that Knobelsdorff used his property in the Tiergarten only

to spend the idyllic summer months there together with his family each

year. But the fact is that this land was intensively cultivated as both

a fruit and a vegetable garden and turned out to be a useful

investment. Knobelsdorff himself read books about the care of fruit

trees and the cultivation of vegetables. One of them (Ecole du Jardin potageur),

contained a taxonomy of various kinds of vegetables, organized

according to their curative powers. This gave rise to the suspicion

that Knobelsdorff hoped for some relief from his chronic health

problems from the plants in his garden. The

structural modifications to the following three palaces are part of the

extensive program that Knobelsdorff tackled on behalf of Frederick II

right after he acceeded to the throne, or a few years thereafter. Monbijou Palace started out as a single-storey pavilion with

gardens on the Spree and was the summer residence, and after 1740 the

widow’s seat, of queen Sophie Dorothee of Prussia, the mother of

Frederick II. The pavilion soon turned out to be too small for the

queen’s representational needs, having only five rooms and a gallery.

Under Knobelsdorff’s leadership the building was expanded in two phases

between 1738 and 1742 into an extensive, symmetrical structure with

side wings and small pavilions. Surfaces with strong colors, gilding,

ornaments and sculptures gave structure to the lengthy building. This

version was gone already by 1755. Up until its almost total destruction

in World War II the facing had a smooth white plaster coating. All

remains of the building were cleared away in 1959/60. Charlottenburg Palace was

hardly used under Frederick William I. His son considered residing

there and right at the beginning of his reign had it enlarged by

Knobelsdorff. Thus a new part of the building arose, east of the

original palace and known as the new wing or Knobelsdorff wing. It

contained two rooms famous for their decoration. The White Hall,

Frederick the Great’s dining and throne room with a ceiling painting by

Pesne, leaves a restrained, almost Classicist, impression. By contrast,

the Golden Gallery with its very rich ornamentation, green and gold

colors is considered the epitome of Frederician rococo.

The contrast between these two neighboring rooms makes clear the range

of Knobelsdorff’s artistic forms of expression. The king’s interest in

Charlottenburg waned as he began to consider Potsdam as a second

official residence, started to build there, and finally lived there.

Charlottenburg Palace was heavily damaged in World War II and after

1945 reconstructed in a form faithful to the original to a large extent. Potsdam City Palace.

This baroque edifice was completed in 1669. After plans for a new

palace residence in Berlin were abandoned, Frederick the Great had the

castle rebuilt by Knobelsdorff between 1744 and 1752, with rich

interior decorations in rococo style. His changes to the frontage had

the goal of lightening up the massive building. Pilasters and figures

of light colored sandstone clearly projected from red plaster surfaces.

Numerous decorative elements were added and the blue-lacquered

copper-covered roofs were crowned with richly decorated chimneys. Many

of these details were soon lost and not replaced. In World War II the

building was badly damaged and 1959/60 what was left was completely

removed. The Brandenburg State Parliament decided to have the City

Palace rebuilt by 2011, at least as to its exterior. Since 2002 a copy

of part of the building, the so-called Fortuna portico, has been

reconstructed at its historic location.

On

January 13, 1745 Frederick the Great arranged for the construction of a

summer house in Potsdam (“Lust-Haus zu Potsdam”). He had made quite

specific sketches of what he desired, and had Knobelsdorff take care of

the realization. They specified a single storey building resting on the

ground of the vineyard terraces

on the southern slope of the Bornstedt Heights in northwest Potsdam.

Knobelsdorff raised objections to this idea; he wanted to increase the

height of the building by adding a souterrain level to serve as a

pedestal, plus a basement, and to move it forward to the edge of the

terraces since it would otherwise look as if it had sunk into the

ground if viewed from the foot of the vineyard hill. Frederick however

insisted on his version. Even the suggestion that his plan increased

the possibility of suffering from gout and

catching cold did not cause Frederick to change his mind. Later he ran

into these very difficulties, but bore them without complaint. After

only two years of construction, Sansoussi Palace (“my little vineyard

house”) was how Frederick referred to it) was dedicated on May 1, 1747.

Frederick the Great usually resided there from May to September; the winter months he spent in the Potsdam City Palace. Evidence

for Knobelsdorff’s artistic versatility is found in his designs for

garden vases, mirror frames, furniture and coaches. This kind of

activity culminated in the design of large representational rooms, such

as the spectator area of the Berlin State Opera Unter den Lindon and

the large rooms in Charlottenburg Palace. Decorative ornamentation was

an important feature of European rococo. Three French masters of this

art, Antoine Watteau, Jules Aurele Meissonier and Jaques de La Joue, had created patterns and models which found wide circulation in the form of etchings and engravings.

Knobelsdorff was obviously especially influenced by Watteau’s work,

whose motifs he had taken over and adapted in Rheinsberg for mirror and

picture frames. This

influence turned out to be determinative for the design of the Golden

Gallery in the New Wing of Charlottenburg Palace, a masterpiece of

Frederician rokoko, built between 1741 and 1746. It was destroyed in

World War II and later rebuilt. The artist, who himself had a lifelong

affinity with nature, created here an artistic realm which was intended

to evoke and glorify nature. At the same time the scenery of the actual

palace park was brought into the room with the help of mirrors. The

gallery is 42 meters long; the walls are covered with chrysoprase green scagliola; ornaments, benches and corbels are

gilded. The walls and ceiling are covered with ornaments based in most

cases on plant motifs. Watteau’s notion of ornamental grotesques — a

frame of fanciful plants and architectonic motifs surrounds a scene

showing trees and people undertaking rural pleasures — clearly often

served as inspiration. The French Church is one of Knobelsdorff’s late works. For the Hugenot congregation he designed a small round building which recalled the Pantheon in

Rome. Construction was carried out by Jan Boumann, whose talents as an

architect were not esteemed by Knobelsdorff, but who was often

preferred for commissions in later years. The church has an oval ground

plan of about 15:20 meters and a free-floating dome which 80 years later Karl Friedrich Schinkel declared to be very daring as to its statics. The modest interior gives the impression of an amphitheater because

of the encircling wooden balcony. As specified by the French Reformed

Church service there were no embellishments — no cross, no baptismal

font, no figural decoration. Frederick II handed over the completed

church to the Potsdam congregation on September 16, 1753, the day of

Knobelsdorff’s death. In

the 19th century Schinkel modified the interior fittings, since they

had in the meantime come into disrepair. The church had been built on a

damp foundation so damages appeared in quick succession. The church had

to be closed several times for periods of years, but in the end it even

managed to survive World War II intact. The latest extensive

renovations took place from 1990 to 2003. In 1753 Knobelsdorff’s long-time liver disease became more troublesome. A journey to the Belgian therapeutic baths at Spa

brought

no relief. On September 7, 1753, only a short while before his death,

Knobelsdorff wrote to the king, “when the pain briefly stopped”. He

thanked him “for all the kindness and all the benefits Your Majesty has

showered on me during my lifetime”. At

the same time he requested that his two daughters be recognized as his

legal heirs. That was problematic because the girls came from a liaison

not befitting his social class. The long-time bachelor Knobelsdorff had

entered into a relationship with the “middle class” daughter of the

Charlottenburg sacristan,

Schöne, in 1746, thereby earning the disapproval of court society.

Frederick II agreed to his request, however with the restriction that

his title of nobility not be bequeathed. Knobelsdorff died on September 16, 1753. Two days later the Berlinische Nachrichten reported,

“On the 16th of this month the honorable gentleman, Mr. George Wentzel,

Baron of Knobelsdorff, artistic director of all royal palaces, houses

and gardens, director-in-chief of all construction in all provinces, as

well as finance, war and domain councillor, departed this life after a

prolonged illness in the 53rd year of his renowned existence.” On September 18 he was buried in the vault of the German Church on Gendarmenmarkt. Four years later his friend Antoine Pesne was buried next to him. When

the church was rebuilt in 1881 these mortal remains were transferred to

one of the cemeteries at Hallisches Tor; his grave was marked with a

marble slab and a putto. This gravesite was destroyed by a bomb in

World War II. Today a simple white marble memorial on an honorary grave

of the State of Berlin in Cemetery No. 1 of the Jerusalem and New

Church congregation brings to mind Knobelsdorff and Pesne.