<Back to Index>

- Physicist Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron, 1799

- Printmaker Honoré Daumier, 1808

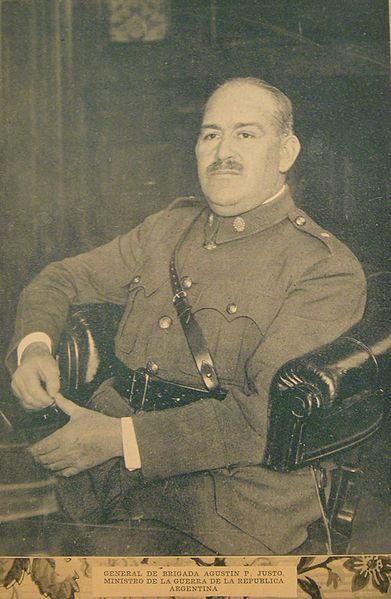

- President of Argentina Agustín Pedro Justo Rolón, 1876

PAGE SPONSOR

General Agustín Pedro Justo Rolón (February 26, 1876 – January 11, 1943) was President of Argentina from February 20, 1932, to February 20, 1938. He was a military man, diplomat, and politician, and was president during the Infamous Decade.

Appointed War Minister by President Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear,

his experience under a civilian administration and pragmatic outlook

earned him the conservative Concordance's nomination for the 1931 campaign.

He was elected president on November 8, 1931, supported by the

political sectors that would form shortly after la Concordancia, an

alliance created between the National Democratic Party (Partido Demócrata Nacional), the Radical Civic Union (Unión Cívica Radical) (UCR), and the Socialist Independent Party (Partido Socialista Independiente). Around the elections there were accusations of electoral fraud, nevertheless, the name patriotic fraud was

used for a system of control established from 1931 to 1943.

Conservative groups wanted to use this to prevent any radicals from

coming to power. During this period there was persistent opposition

from the supporters of Yrigoyen, an earlier president, and from the Radical Civic Union. The outstanding diplomatic work of his Foreign Minister, Carlos Saavedra Lamas,

was one of the greatest accomplishments of his administration, stained

by constant accusations of corruption and of delivering the national

economy into the hands of foreign interests, the British in particular, with whom his vice-president Julio A. Roca, Jr. had signed the Roca-Runciman Treaty. His name was mentioned as a candidate a new period during the unsteady government of Ramón Castillo, but his early death at 66 thwarted his plans. He worked on a preliminary study for the complete works of Bartolomé Mitre, whom he admired profoundly. Justo

took part in the coup of 1930, becoming president two years later

thanks to widespread electoral fraud. His presidency was part of the

period known as the Infamous Decade, which lasted from 1930 until 1943.

He established the country's central bank and introduced a nationwide income tax. Agustín Pedro Justo was buried in La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. Justo was born in Concepción del Uruguay, Entre Ríos Province. His father, also named Agustín, had been governor of Corrientes Province and was soon a national deputy. He was active in politics, and soon after his son was born he moved with his family to Buenos Aires. His mother Otilia Rolón, came from a traditional Corrientes family. When he was 11 Justo went to the Colegio Militar de la Nación (National Military College). As a cadet, he joined with various other students and participated in the Revolución del Parque,

taking the weapons off the guards to add to the column of the

revolutionaries. Arrested and later given amnesty, he graduated with

the rank of ensign. Without abandoning his military career, he studied engineering at the University of Buenos Aires.

In 1895 he was promoted to second lieutenant. In 1897 he became first

lieutenant. In 1902 he became a captain. Having attained a civil

engineering degree at the University of Buenos Aires, a governmental

decree validated his title as a military engineer in 1904. He was appointed as teacher at the Escuela de Aplicación para Oficiales.

With his promotion to the rank of major two years later he was proposed

for the school of mathematics at the Military Academy and for the

studies of telemetry and semaphores at the Escuela Nacional de Tiro (National Gunnery School), which would be granted in 1907. The following year, he received the nomination as executive officer in the Batallón de Ferrocarrileros,

at the same time in which they were promoting him to be subdirector at

the gunnery school. With the rank of Lieutenant Colonel he completed

diplomatic actions, becoming military attaché to the Argentina's envoy at the centennial festivities in Chile in 1910. His return to Argentina was to Córdoba, as commander of the Fourth Artillery Brigade. In

1915, during the term of office of Victorino de la Plaza, he was

appointed director of the Military College, a post where he would

remain for the following seven years. The great influence of this

position helped him to weave contacts in political circles, just as in

the military. Pursuant to the radical anti-personalist political branch (those that opposed the party leadership of Hipólito Yrigoyen), he established good relations with Marcelo T. de Alvear. During his tenure he enlarged the curriculum of the college and promoted the formation of the faculty. During

Alvear's administration in 1922 he left the Military College to become

the Minister of War. Promoted to the rank of brigadier general on

August 25, 1923, Justo requested an increase of the defense budget to

get equipment and improve the Army infrastructure. He also fomented the

reorganization of the armed forces structure. At the end of 1924 he was sent as plenipotentiary to Peru, where they were celebrating the centennial of the Battle of Ayacucho.

During the next few years he temporarily was the Minister of

Agriculture and Public Works, besides holding the post as Minister

of War, which he would not abandon until the end of the term of office

of Alvear. In 1927 he had received the promotion to General de División (Major General). With his constant anti-personalist temperament, Justo supported the candidates Leopoldo Melo and Vicente Gallo,

of the Alvear Line of the UCR. Before the triumph of the formula of

Yrigoyen and Beiró, who began in 1928 their second term of

office with massive support of the voters and the majority in the House

of Representatives, Justo received invitations of the ever more

organized right to join the shock program against the radical caudillo. Although close to the concepts of the publications La Nueva República (The New Republic) — managed by Ernesto Palacios and the brothers Rodolfo and Julio Irazusta — and La Fronda,

under the direction of Francisco Uriburu, they stayed close to the need

of "order, hierarchy and authority". He did not adhere closely to them,

the program of suppression of a republican government and their

substitution with a corporative system, similar to the fascists in Italy

and Spain, went against his liberal vocation. Around

Justo another faction assembled, not any less intent on taking arms

against the constitutional government of Yrigoyen. Actively promoted by

general José Luis Meglione, a Justo classmate, and by colonel

Luis J. García, who soon would be one of the heads of the Grupo de Oficiales Unidos, he wrote for the newspapers La Nación and Crítica.

Declarations made by Justo in July 1930 about the inconvenience of

military intervention, which would put the constitutional rule of law

in danger, testify to the opposition between the factions. By contrast

with the more radicalized Argentine Navy, a significant part of the

Army supported the ideas proposed by Justo, with the notable exception

of the nationalist core that soon would converge at the Grupo de Oficiales Unidos.

Before the promise of José Félix Uriburu, the head of an

extremist group, to maintain institutional order, Justo gave his

agreement to the coup, which he expressed on the early morning of September 6,

thus starting a military government in Argentina for the first time

since the signing of the Constitution. He did not join the government's

direction nor, in the first instance, the governing group, which was

led by Uriburu with a cabinet that was composed largely of local

lobbyists of the multinational oil companies. Justo

expressly sought to distance himself from Uriburu, who counted on a

large group of supporters among the military officials but could not

get the same support from the political parties, which quickly divided

themselves after Yrigoyen's death, the focus of the antipathy against

him. He rejected the vice-presidency that Uriburu offered him, and he

only briefly accepted the command of the army, resigning soon after. In

Buenos Aires Province, Uriburu did not manage to implement the

corporate model with which he wished to replace the republican system,

and this failure cost him the political career of his Interior

Minister, Matías Sánchez Sorondo. Justo again rejected

the offers of Uriburu to join the government and form a coalition. With

the support of an alliance of the conservative National Democratic

Party, the Independent Socialist Party, and the most anti-personalist

faction of the Radical Party (then to be the Coalition of Parties for

Democracy), he ran for president on the elections of November 8, 1931.

With Yrigoyen's faction banned from the elections and its supporters

using the strategy of "revolutionary abstention", Justo easily won

against Lisandro de la Torre and Nicolás Repetto, although under

suspicion of fraud. Julio Argentino Roca, Jr., from the conservative

faction, joined him as Vice-President. Justo

became president on February 20, 1932. In addition to political turmoil

caused by the coup, he had to make progress on the problems relating to

the Great Depression, which had put an end to commercial profits and the full employment enjoyed

by the Yrigoyen and Alvear administrations. His first minister of the

Treasury, Alberto Hueyo, took very restrictive measures against the

economy. The independent socialist Antonio de Tomaso joined him in

Agriculture. He reduced public expenses, and restricted the

circulation of currency and applied harsh fiscal measures. An empréstito patriótico,

or patriotic loan, was made, attempting to strengthen the financial

coffers. The first of these measures was imposed on gasoline. It was

meant to finance the newly-created Dirección Nacional de

Vialidad, or the National Office of Public Highways, which undertook

the betterment of the highway network. The difficulies for Hueyo's

program would finally convince Justo to adopt this model, (de

índole dirigista), in his economic policy. In addition, he

encouraged the project of the mayor of Buenos Aires, Mariano de Vedia y

Mitry, who undertook an ambitious project of urban organization,

opening the Diagonales Norte y Sur, paving Avenue General Paz, widening

Avenue Corrientes, constructing the first stretch of Avenue 9 de Julio

and building the Obelisk of Buenos Aires. The

substitution of Hueyo by the socialist Frederico Pinedo would mark a

change in the political scene in the government. The intervention of

the government in the economy was more significant, creating the Junta

Nacional de Granos, or the National Grain Committee, and of Meat, and

soon after, with the advice of English economist Otto Niemeyer, the

creation of the Banco Central de la República Argentina, or the

Central Bank of the Argentine Republic. The

radical opposition was very significant. On April 5, 1931 the political

ideology of the supporters of Yrigoyen had won the election for

governor in the province of Buenos Aires against the hopes of Uriburu

and Sánchez Sorondo; though the military government rings, cost

the career of the Minister and forced Uriburu to give up his power.

Before this, soldiers loyal to the constitutional government of

Yrigoyen, with the support of armed civilians, organized insurrections

to restore that earlier government. The first of these was directed by

the Yrigoyenist general Severino Toranzo in February 1931. In June, in

Curuzú Cuatiá in the province of Corrientes, they

assassinated Colonel Regino Lescano, who was preparing an Yrigoyenist

mobilization. In December, before an attempted coup led by Lieutenant

Colonel Atilio Cattáneo, Justo decreed a state of siege, and

again imprisoned the old Yrigoyen, and also arrested Alvear, Ricardo

Rojas, Honorio Pueyrredón, and other leaders of the party. In

1933, the attempted coups continued. Buenos Aires, Corrientes, Entre

Rios, and Misiones would be the stage of radical uprisings, which would

not end before more than a thousand people were detained. Seriously

ill, Yrigoyen was returned to Buenos Aires and kept under house arrest.

He died on June 3, and his burial in La Recoleta Cemetery was the occasion of a mass demonstration. In December, during a meeting

of the national convention of the UCR, a joint uprising of the military

and politicians broke loose in Santa Fe, Rosario, and Paso de los

Libres. José Benjamin Abalos, who was Yrigoyen's ex-Minister,

and Colonel Roberto Bosch were arrested during the uprising and the

organizers and leaders of the party were imprisoned at Martín

García. Alvear, Justo's former patron, was exiled, while others

were detained in the penitentiary in Ushuaia. One

of the most controversial successes of the presidency of Justo took

place in 1933, when the measures of production protectionism that were

adopted by the UK led Justo to send his vice-president at the head of a

technology delegation, to deal with the adoption of a commercial agreement that might benefit Argentina. At the 1932 Ottawa Conference,

the British had adopted measures that favored imports from their own

colonies and dominions. The pressure from the Argentine landowners for

the government to restore trade with the main buyer of Argentine

grain and meat had been very strong. Led by the president of the

British Trade Council, Viscount Walter Runciman, negotiations were intense and resulted in the signing on April 27 of the Roca-Runciman Treaty.

The

treaty created a scandal because the UK allotted Argentina a quota less

than any of its other dominions. In exchange for many concessions to

British companies, 390,000 tons of meat per year were allotted to

Argentina. British refrigerated shippers arranged 85% of exportation.

The tariffs of the railways operated by the UK were not regulated. They

had not established customs fees over coal. They had given special

dispensation to the British companies with investments in Argentina.

They had reduced the prices of their exports. Many problems resulted

from the declarations of vice-president Roca, who affirmed after

the signing of the treaty that "by its economic importance, Argentina

resembled just a large British dominion." Lisandro de la Torre,

one of his principal and most vociferous opponents, mocking the words

of Roca in an editorial, wrote that "in these conditions we wouldn't be

able to say that Argentina had been converted into a British dominion

because England does not take the liberty to impose similar

humiliations upon its dominions." In

the National Democratic Party, one of those who had supported the

nomination of Justo for President, had split because of this

controversy. Finally, the Senate rescinded the treaty on July 28. Many

workers strikes followed the deliberations, especially in Santa Fé Province, which ended with government intervention.