<Back to Index>

- Physicist Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius, 1822

- Composer Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev, 1837

- Major General of the British Army James Wolfe, 1727

PAGE SPONSOR

General James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer, known for his training reforms but remembered chiefly for his victory over the French in Canada. The son of a distinguished general, he received his first commission at a young age and saw extensive service in Europe where he fought during the War of the Austrian Succession. His service in Flanders and in Scotland, where he took part in the suppression of the Jacobite Rebellion, brought him to the attention of his superiors. The advancement of his career was halted by the Peace Treaty of 1748 and he spent much of the next eight years in garrison duty in the Scottish Highlands.

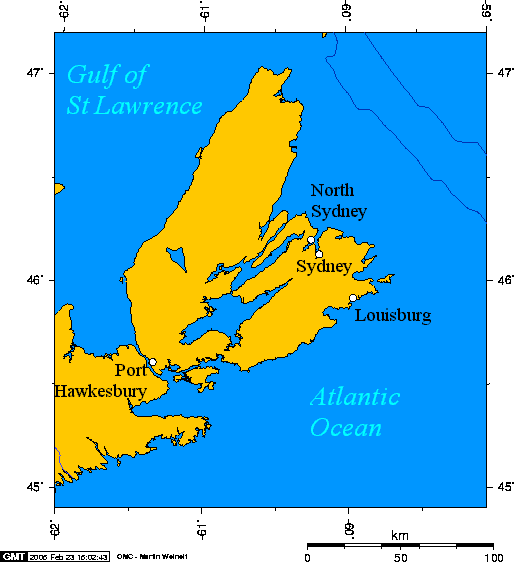

The outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756 offered Wolfe fresh opportunities for advancement. His part in the aborted attack on Rochefort in 1757 led William Pitt to appoint him second-in-command of an expedition to capture Louisbourg. Following the success of this operation he was made commander of a force designated to sail up the Saint Lawrence River to capture Quebec. After a lengthy siege Wolfe defeated a French force under Montcalm allowing British forces to capture the city. Wolfe was killed at the height of the battle by a French cannon shot. Wolfe's part in the taking of Quebec in 1759 earned him posthumous fame and he became an icon of Britain's victory in the Seven Years War and subsequent territorial expansion. He was depicted in the painting The Death of General Wolfe. James Peter Wolfe was born on 2 January 1727 at Westerham, Kent, the older of two sons of Colonel Edward Wolfe, a veteran soldier of Irish origin, and the former Henrietta Thompson. His uncle was Edward Thompson MP,

a distinguished politician. His relatively humble birth marked him out

from many army officers at the time, who were disproportionatly drawn

from the aristocracy. Wolfe's childhood home in Westerham has been preserved in his memory under the name Quebec House. Around 1738, the family moved to Greenwich, in London. From his earliest years, Wolfe was destined for a military

career, entering his father's 1st Marine regiment as a volunteer at the

age of thirteen. Illness prevented him from taking part in a large expedition against Spanish-held Cartagena in 1740, and his father sent him home a few months later. He was fortunate to miss what proved to be a disaster for the British forces at the Siege of Cartagena during the War of Jenkins' Ear with most of the expedition dying from disease.

In 1740 the War of the Austrian Succession broke

out in Europe. Although initially Britain did not actively intervene,

the presence of a sizable French army near the border of the Austrian Netherlands compelled

the British to send an expedition to help defend the territory of their

Austrian ally in 1742. Wolfe transferred to the 12th Regiment of Foot, a British Army infantry regiment, and set sail for Flanders some months later where the British took up position in Ghent. Here, Wolfe was promoted to Lieutenant and made adjutant of his battalion. His first year on the continent was a frustrating one as, despite rumours of a British attack on Dunkirk, they remained inactive in Flanders. In 1743, he was joined by his younger brother, Edward, who had received a commission in the same regiment. That

year the Wolfe brothers took part in an offensive launched by the

British. Instead of moving southwards as expected, the British and

their allies instead thrust eastwards into Southern Germany where they

faced a large French army. The army came under the personal command of George II but in June he appeared to have made a catastrophic mistake which left the Allies trapped against the River Main and surrounded by enemy forces in "a mousetrap". Rather

than contemplate surrender, George tried to rectify the situation by

launching an attack on the French positions near the village of

Dettingen. Wolfe's regiment was involved in heavy fighting, as the two

sides exchanged volley after volley of musket fire.

His regiment had suffered the highest casualties of any of the British

infantry battalions, and Wolfe had his horse shot from underneath him. Despite

three French attacks the Allies managed to drive off the enemy, who

fled through the village of Dettington which was then occupied by the

Allies. However, George failed to adequately pursue the retreating

enemy allowing them to escape. In spite of this the Allies had successfully thwarted the French move into Germany, safeguarding the independence of Hanover.

Wolfe's activities at Battle of Dettington, came to the attention of the Duke of Cumberland who had been close to him during the battle when they came under enemy fire. A year later, he became a captain of the 45th Regiment of Foot. After the success of Dettington, the 1744 campaign was another frustration as the Allies forces now led by George Wade failed to compete their objective of capturing Lille,

fought no major battles, and returned to winter quarters at Ghent

without anything to show for their efforts. Wolfe was left devastated

when his brother Edward died, probably of consumption, that autumn. Wolfe's regiment was left behind to garrison Ghent, which meant they missed the Allied defeat at the Battle of Fontenoy in

May 1745 during which Wolfe's former regiment suffered extremely heavy

casualties. Wolfe's regiment was then summoned to reinforce the main

Allied army, now under the command of the Duke of Cumberland. Shortly after they had departed Ghent, the town was suddenly attacked by the French who captured it and its garrison. Having narrowly avoided becoming a French prisoner, Wolfe was now made a brigade major. In October 1745, Wolfe's regiment was urgently recalled to Britain to deal with the Jacobite rising which had broken out. In September Jacobite forces had won the Battle of Prestonpans and captured Edinburgh. They were poised to march into England where they expected a mass Jacobite rebellion to break out that would topple George II and his Hanoverian Dynasty and replace them with the Old Pretender 'James III'. Wolfe and his regiment were initially sent to Newcastle to

bolster a force commanded by General Wade to prevent a Jacobite advance

along the east coast. Instead the rebels bypassed Wade's army at

Newcastle, by heading down the opposite coast via Carlisle. The Jacobites reached as far as Derby and only a force of militia stood between them and London.

However, having encountered limited English support for their cause the

Jacobites decided to withdraw and by the end of the year they were back

in Scotland and government forces prepared for what they believed would be a relatively easy campaign that would crush the rebels. Wolfe served in Scotland in 1746 as aide-de-camp under General Henry Hawley in the campaign to defeat the Jacobite forces of Charles Edward Stuart. In this capacity, Wolfe participated in the Battle of Falkirk and the Battle of Culloden. At Culloden, he famously refused to shoot a wounded highlander when he was ordered by the Duke of Cumberland stating

that he would rather resign his post than sacrifice his honour.

However, the gesture did not work, and the man was shot by Cumberland

himself. It has been suggested that it may have been Hawley who gave

the order rather than Cumberland. This act may have been a cause for his later popularity among the Royal Highland Fusiliers,

whom he would command in North America. After this he took part in the

pacification of the Highlands, designed to destroy the remnants of the

rebellion. In January 1747 Wolfe returned to the Continent and the War of the Austrian Succession, serving under Sir John Mordaunt. The French had taken advantage of the absence of Cumberland's British troops and had made advances in the Austrian Netherlands including the capture of Brussels. The major French objective in 1747 was to capture Maastricht considered the gateway to the Dutch Republic. Wolfe was part of Cumberland's army, which marched to protect the city from the advancing French force under Marshal Saxe. On 2 July Wolfe participated in the Battle of Lauffeld, where he was wounded and received an official commendation for services to Britain. Lauffeld was the largest battle in terms of numbers in which Wolfe fought, with the combined strength of both armies totalling over 140,000. Following their narrow victory at Lauffeld, the French captured Maastricht and seized another strategic fortress at Bergen-op-Zoom. Both sides remained poised for further offensives, but an armistice halted the fighting. In 1748, at just 21 years of age and with service in seven campaigns, Wolfe returned to Britain following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle which ended the war. Under the treaty, Britain and France had agreed to

exchange all captured territory and the Austrian Netherlands were returned to Austrian control. Once home, he was posted to Scotland and garrison duty, and a year later was made a major, in which rank he assumed command of the 20th Regiment, stationed at Stirling. In 1750, Wolfe was confirmed as Lieutenant Colonel of the regiment. During

the eight years Wolfe remained in Scotland, he wrote military pamphlets

and became proficient in French, as a result of several trips to Paris. Despite struggling with bouts of ill health suspected to be tuberculosis, he also tried to keep himself mentally fit by teaching himself Latin and mathematics,

also Wolfe trained his body too, pushing himself to improve his

swordsmanship and attending sessions where he learned about science and

how to improve his leadership skills. Wolfe worked hard despite his

illness and learned from many people. Wolfe had made the number of

influential acquaintances during the recent war. His father, who was

now a General, also actively assisted his son's career. In 1752 Wolfe was granted extended leave, and he first went to Ireland staying in Dublin with his uncle and visiting Belfast and the site of the Battle of the Boyne. After

a brief stop at his parents house in Greenwich he received permission

from the Duke of Cumberland to go abroad and he crossed the Channel to

France. He took in the sights of Paris including the Tuileries Gardens and visited the Palace of Versailles. He was frequently entertained by the British Ambassador, Earl of Albermarle, with whom he had served in Scotland in 1746. Albermarle arranged an audience for Wolfe with Louis XV. While in Paris Wolfe spent money on improving his French and his fencing skills. He

applied for further leave so he could witness a major military exercise

by the French army, but he was instead urgently ordered home. He

rejoined his regiment in Glasgow. By

1754 Britain's declining relationship with France made a fresh war

imminent and fighting broke out in North America between the two sides. In 1756, with the outbreak of open hostilities with France, Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in Canterbury, where his regiment had been posted to guard his home county of Kent against a French invasion threat. He was extremely dispirited by news of the loss of Minorca in

June 1756, lamenting what he saw as the lack of professionalism amongst

the British forces. Despite a widespread belief that French landing was

imminent, Wolfe thought that it was unlikely his men would be called

into action. In spite of this, he trained them diligently and issued fighting instructions to his troops. As the threat of invasion decreased, the regiment were marched to Wiltshire.

Despite the initial setbacks of the war in Europe and North America the

British were now expected to take the offensive and Wolfe anticipated

playing a major role in future operations. However, his health was

beginning to decline which led to suspicions that he was suffering, as

his younger brother had, from consumption. Many of his letters to his parents began to assume a slightly fatalistic note in which he talked of the likelihood of an early death. In 1757 Wolfe participated in the British amphibious assault on Rochefort, a seaport on the French Atlantic coast. A major Naval Descent, it was designed to capture the town, and relieve pressure on Britain's

German allies who were under French attack in Northern Europe. Wolfe

was selected to take part in the expedition partly because of his

friendship with its commander, Sir John Mordaunt. In addition to his regimental duties, Wolfe also served as Quartermaster General for the whole expedition. The force was assembled on the Isle of Wight and

after weeks of delay finally sailed on 7 September. The

attempt failed as, after capturing an island offshore, the British made

no attempt to land on the mainland and press on to Rochefort and

instead withdrew home. While their sudden appearance off the French

coast had spread panic throughout France, it had little practical

effect. Mordaunt was court-martialed for his failure to attack Rochefort, although acquitted. Nonetheless,

Wolfe was one of the few military leaders who had distinguished himself

in the raid – having gone ashore to scout the terrain, and having

constantly urged Mordaunt into action. He

had at one point told the General that he could capture Rochefort if he

was given just 500 men but Mordaunt refused him permission. While

Wolfe was irritated by the failure, believing that they should have

used the advantage of surprise and attacked and taken the town

immediately, he was able to draw valuable lessons about amphibious

warfare that influenced his later operations at Louisbourg and Quebec. As a result of his actions at Rochefort, Wolfe was brought to the notice of the Prime Minister, William Pitt, the Elder.

Pitt had determined that the best gains in the war were to be made in

North America where France was vulnerable, and planned to launch an

assault on French Canada. Pitt now decided to promote Wolfe over the heads of a number of senior officers. On 23 January 1758, James Wolfe was appointed as a Brigadier General, and sent with Major General Jeffrey Amherst to lay siege to Fortress of Louisbourg in New France (located in present-day Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia). Louisbourg stood near the mouth of the St Lawrence River and its capture was considered essential to any attack on Canada from the east. An expedition the previous year had

failed to seize the town because of a French naval build-up. For 1758

Pitt sent a much larger Royal Navy force to accompany Amherst's troops. Wolfe

distinguished himself in preparations for the assault, the initial

landing and in the aggressive advance of siege batteries. The French

capitulated in June of that year. The

British had initially planned to advance along the St Lawrence and

attack Quebec that year, but the onset of winter forced them to

postpone to the following year. Similarly a plan to capture New Orleans was rejected,

and Wolfe returned home to England. Wolfe's part in the taking of the

town brought him to the attention of the British public for the first

time. The news of the victory at Louisbourg was tempered by the failure

of a British force advancing towards Montreal at the Battle of Carillon and the death of George Howe, a widely respected young general who Wolfe described as the "the best officer in the British Army".

As Wolfe had comported himself admirably at Louisbourg, William Pitt the Elder chose him to lead the British assault on Quebec City the following year, with the rank of major general. Amherst had been appointed as Commander-in-Chief in North America,

and he would lead a separate and larger force that would attack Canada

from the south. He insisted on the choice of his friend, the Irish officer Guy Carleton as Quartermaster General or threatened to resign the command. Once

this was granted, he began making preparations for his departure. Pitt

was determined to once again give operations in North America top

priority, as he planned to weaken France's international position by

capturing their colonies. Despite

the large build-up of British forces in North America, the strategy of

dividing the army for separate attacks on Canada meant that once Wolfe

reached Quebec the French commander Louis-Joseph de Montcalm would have a local superiority of troops having raised large numbers of Canadian militia to defend their homeland. The

French had not initially expected the British to approach from the

east, believing the St Lawrence River was impassible for such a large

force, and had prepared to defend Quebec from the south and west. An

intercepted copy of British plans gave Montcalm several weeks to

improve the fortifications protecting Quebec from an amphibious attack

by Wolfe. Montcalm's

goal was to try and prevent the British from capturing Quebec, thereby

maintaining a French foothold in Canada. The French government believed

a peace treaty was likely to be agreed the following year and so they

directed the emphasis of their own efforts towards victory in Germany

and a Planned invasion of Britain hoping

thereby to secure the exchange of captured territories. For this plan

to be successful Montcalm had only to hold out until the start of

winter. Wolfe had a narrow window to capture Quebec during 1759 before

the St Lawrence began to freeze trapping his force. Wolfe's army was assembled at Louisbourg.

Eager to begin the campaign, after several delays, he pushed ahead with

only part of his force and left orders for further arrivals to be sent

on down the St Lawrence after him. The British army laid siege to the city for three months. During that time, Wolfe issued a written document, known as Wolfe's Manifesto, to the French-Canadian (Québécois)

civilians, as part of his strategy of psychological intimidation. In

March 1759, prior to arriving at Quebec, Wolfe had written to Amherst:

"If, by accident in the river, by the enemy’s resistance, by sickness

or slaughter in the army, or, from any other cause, we find that Quebec

is not likely to fall into our hands (persevering however to the last

moment), I propose to set the town on fire with shells, to destroy the

harvest, houses and cattle, both above and below, to send off as many

Canadians as possible to Europe and to leave famine and desolation

behind me; but we must teach these scoundrels to make war in a more

gentleman like manner." This manifesto has widely been regarded as

counter-productive as it drove many neutrally-inclined inhabitants to

actively resist the British, swelling the size of the militia defending

to Quebec to as many as 10,000.

After

an extensive yet inconclusive bombardment of the city, Wolfe initiated

a failed attack north of Quebec at Beauport, where the French were

securely entrenched. As the weeks wore on the chances of British

success lessened, and Wolfe grew despondent. Amherst's large force

advancing on Montreal had made very slow progress, ruling out the

prospect of Wolfe receiving any help from him. Wolfe then led 200 ships with 9,000 soldiers and 18,000 sailors on a very

bold and risky amphibious landing at the base of the cliffs west of

Quebec along the St. Lawrence River.

His army, with two small cannons, scaled the cliffs early in the

morning of September 13, 1759, surprising the French under the command

of the Marquis de Montcalm,

who thought the cliffs would be unclimbable. Faced with the possibility

that the British would haul more cannons up the cliffs and knock down

the city's remaining walls, the French fought the British on the Plains of Abraham.

They were defeated after fifteen minutes of battle, but when Wolfe

began to move forward, he was shot three times, once in the arm, once

in the shoulder, and finally in the chest. Historian Francis Parkman describes the death of Wolfe:

They

asked him [Wolfe] if he would have a surgeon; but he shook his head,

and answered that all was over with him. His eyes closed with the

torpor of approaching death, and those around sustained his fainting

form. Yet they could not withhold their gaze from the wild turmoil

before them, and the charging ranks of their companions rushing through

the line of fire and smoke. "See how they run." one of the officers exclaimed, as the French fled in confusion before the leveled bayonets. "Who run?" demanded Wolfe, opening his eyes like a man aroused from sleep. "The enemy, sir," was the reply; "they give way everywhere." "Then,"

said the dying general, "tell Colonel River, to cut off their retreat

from the bridge. Now, God be praised, I die contented," he murmured;

and, turning on his side, he calmly breathed his last breath. The Battle of the Plains of Abraham is

notable for causing the deaths of the top military commander on each

side: Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at

Quebec enabled an assault on the French at Montreal the following year. With the fall of that city, French rule in North America, outside of the tiny islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, came to an end. Wolfe's body was returned to Britain and interred in the family vault in St Alfege Church, Greenwich, alongside his father (who had died in March 1759).

Wolfe

was renowned by his troops for being demanding on himself and on them.

Although he was prone to illness, Wolfe was an active and restless

figure. Amherst reported that Wolfe seemed to be everywhere at once.

There was a story that when someone in the British Court branded the

young Brigadier mad, King George II retorted, "Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals." Some biographers, including Richard Garrett have suggested Wolfe may have been a repressed homosexual, although his behavioral patterns were fairly typical of the noblemen of the time. A cultured man, in 1759 during the Seven Years War, before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham Wolfe is said to have recited Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard to his officers, adding: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec tomorrow".