<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Marie Ennemond Camille Jordan, 1838

- Novelist Umberto Eco, 1932

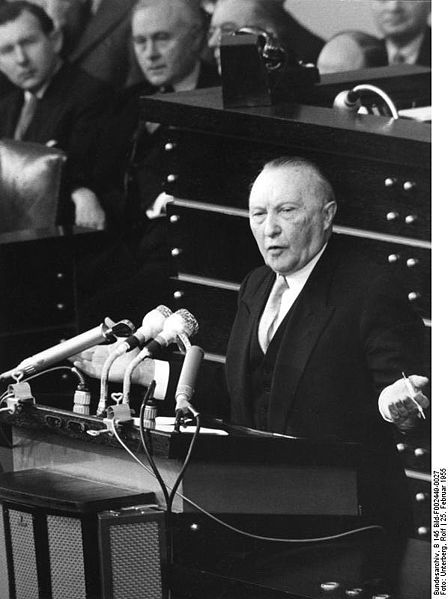

- Chancellor of Germany Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer, 1876

PAGE SPONSOR

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman.

Although his political career spanned sixty years, beginning as early as 1906, he is most noted for his role as the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (then known as West Germany) from 1949 – 1963 and chairman of the Christian Democratic Union from 1950 to 1966. He was the oldest chancellor ever to serve Germany, beginning his first ministry at the age of 73 and leaving at the age of 87. His 14-year tenure was the second-longest for a German Chancellor (behind Otto von Bismarck) until Helmut Kohl passed him in 1996. As a Catholic Centre Party politician in the Weimar Republic, he served as Mayor of Cologne (1917 – 1933) and president of the Prussian State Council (1922 – 1933). As such he was one of the most prominent politicians of interwar Prussia and a leading democratic adversary of Prime Minister Otto Braun.

Konrad

Adenauer was born as the third of five children of Johann Konrad

Adenauer (1833 – 1906) and his wife Helene (1849 – 1919) (née Scharfenberg) in Cologne, Rhenish Prussia.

His siblings were August (1872 – 1952), Johannes (1873 – 1937), Lilli

(1879 – 1950) and Elisabeth, who died shortly after birth in c. 1880. In

1894, he completed his Abitur and started to study law and politics at the universities of Freiburg, Munich and Bonn. He was a member of several Roman Catholic students’ associations under the K.St.V. Arminia Bonn in Bonn. He finished his studies in 1901. Afterwards he worked as a lawyer at the court in Cologne. As a devout Roman Catholic, he joined the Centre Party in

1906 and was elected to Cologne’s city council in the same year. In

1909, he became Vice-Mayor of Cologne. From 1917 to 1933, he served as

Mayor of Cologne. He had the unpleasant task of heading Cologne in the

era of British occupation following the First World War and lasting until 1926. He managed to establish faithful relations with the British military authorities and flirted with Rhenish separatism (a Rhenish state as part of Germany, but outside Prussia). During the Weimar Republic,

he was president of the Prussian State Council (Preußischer

Staatsrat) from 1922 to 1933, which was the representative of the

Prussian cities and provinces. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Centre Party lost the elections in Cologne and Adenauer fled to the abbey of Maria Laach, threatened by the new government after he refused to shake hands with a

local Nazi leader. His stay at this abbey, which lasted for a year, was

cited by its abbot after the war, when accused by Heinrich Böll and others of collaboration with the Nazis. According to Albert Speer in his book Spandau: The Secret Diaries,

Hitler expressed admiration for Adenauer, noting his building of a road

circling the city as a bypass, and of a “green belt” of parks. However,

both Hitler and Speer felt that Adenauer’s political views and

principles made it impossible for him to play any role within the Nazi movement or be helpful to the Nazi party. He was imprisoned briefly after the Night of the Long Knives in

mid-1934. During the next two years, he changed residences often for

fear of reprisals against him by the Nazis, while living on his

pension. In 1937, he was successful in claiming at least some

compensation for his once confiscated house and managed to live in

seclusion for some years. After the failed assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944, he was imprisoned for a second time as an opponent of the regime. He fell ill and credited Eugen Zander, the communist Kapo of

the camp near Bonn, with saving his life by getting him transferred to

a hospital. He was then re-arrested, but in the absence of any evidence

against him was released from Brauweiler Abbey in November. Shortly after the war ended the Americans installed him again as Mayor of Cologne, but the British Director of Military Government in Germany, Gerald Templer, dismissed him for what he said was his alleged incompetence. After his dismissal as Mayor of Cologne, Adenauer devoted himself to building a new political party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), which he hoped would embrace both Protestants and

Roman Catholics in a single party. In January 1946, Adenauer initiated

a political meeting of the future CDU in the British zone in his role

as doyen (the oldest man in attendance, Alterspräsident) and was informally confirmed as its leader. Adenauer

worked diligently at building up contacts and support in the CDU over

the next years, and he sought with varying success to impose his

particular ideology on the party. His was an ideology at odds with many

in the CDU, who wished to unite socialism and Christianity; Adenauer preferred to stress the dignity of the individual, and he considered both communism and Nazism materialist world views that violated human dignity. Adenauer’s leading role in the CDU of the British zone won him a position at the Parliamentary Council of 1948, called into existence by the Western Allies to draft a constitution for the three western zones of Germany.

He was the chairman of this constitutional convention and vaulted from

this position to being chosen as the first head of government once the

new “Basic Law” had been promulgated in May 1949. Adenauer

was reportedly critical of the Catholic hierarchy for not criticizing

the Nazis loudly enough, and he is cited for this in the book Constantine's Sword by John Cornwell. After the German federal election, 1949 at age 73, Adenauer was elected the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundeskanzler) after World War II with the support of his own CDU, the Christian Social Union and the liberal Free Democratic Party. Due to his age, it was initially thought he would only be a caretaker.

However, he held this position from 1949 to 1963, a period which spans

most of the preliminary phase of the Cold War.

During this period, the post-war division of Germany was consolidated with the establishment of two separate German states, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). The first elections to the Bundestag of West Germany were held on 15 August 1949, with the Christian Democrats emerging as the strongest party. Theodor Heuss was

elected first President of the Republic, and Adenauer was elected

Chancellor on 16 September 1949. He also had the new "provisional"

capital of the Federal Republic of Germany established at Bonn, which was only 15 kilometers away from his hometown, rather than at Frankfurt am Main. At the Petersberg Agreement in

November 1949 he achieved some of the first concessions granted by the

Allies, such as a decrease in the number of factories to be dismantled,

but in particular his agreement to join the International Authority for the Ruhr led to heavy criticism. In the following debate in parliament Adenauer stated: The opposition leader Kurt Schumacher responded by labeling Adenauer "Chancellor of the Allies." When the rebellion within the Soviet sector of Germany "was

unceremoniously and brutally suppressed by the Red Army" in June 1953,

"Adenauer quickly appreciated [that the event] strengthened his

electoral hand" and he was handily reelected to a second term as

Chancellor. The majority was large enough that his CDU/CSU party coalition could dispense with the FDP as a partner in government. The

election of 1957 essentially dealt with national matters and would

"revolve around the question [of] whether Germany and Europe remain

Christian or become Communist." Adenauer

had brought home the last POWs from Soviet labor camps — "which was

greeted with jubilation," his recent accomplishment in pension reform

"was enormously popular," and his assurance of "no experiments" allowed

him to gain reelection to a third term as Chancellor with the CDU/CSU

winning convincingly, "the first time that a single party had won an

outright majority in German electoral history" in a free election. "His

personal position could no longer be seriously challenged. At the age

of eighty-one, he was almost the un-crowned king of Germany." The

temper had changed by election time in September 1961. Adenauer had

tarnished his image when he announced he would run for the office of

federal president in 1959, only to pull out when he came to the

realization that his vision of a much more powerful presidency conflicted with the Basic Law and the precedent established by the departing and respected Theodor Heuss. The construction of the Berlin Wall in

August 1961 and the sealing of borders by the East Germans made his

government look weak. His "reaction was ... lame;" he eventually flew

to Berlin, but he appeared to have "lost his once instinctive,

ultra-swift power of judgment." After

failing to keep their majority in the general election 36 days after

the wall went up, the CDU/CSU again needed to include the FDP in a

coalition government. To strike a deal, Adenauer was forced to make two

concessions: to relinquish the chancellorship before the end of the new

term, his fourth, and to replace his foreign minister. However,

contemporary critics accused Adenauer of cementing the division of

Germany, sacrificing reunification and the recovery of territories lost

in the westward shift of Poland and the Soviet Union.

"In his view, he said with the greatest emphasis, full integration into

Western Europe was a precondition of the reunification of Germany." During the Cold War, the United States was "aiming for a West German armed force, after their [U.S.] costly experience in the Korean War," and Adenauer linked this rearmament concept to West German sovereignty and entry into NATO. In 1952, the Stalin Note, as it became known, "caught everybody in the West by surprise." It

offered to unify the two German entities into a single, neutral state

with its own, non-aligned national army to effect superpower

disengagement from Central Europe.

Adenauer and his cabinet were unanimous in their rejection of the

Stalin overture, they shared the Western Allies’ suspicion about the

genuineness of that offer and supported the Allies in their cautious

replies. Adenauer’s flat rejection was, however, out of step with

public opinion; he then realized his mistake and he started to ask

questions. Critics denounced him for having missed an opportunity for German reunification.

The Soviets sent a second note, courteous in tone. Adenauer by then

understood that "all opportunity for initiative had passed out of his

hands," and the matter was put to rest by the Allies. Given the realities of the Cold War,

German reunification and recovery of lost territories in the east were

not realistic goals as both of Stalin's notes specified the retention

of the existing "Potsdam"-decreed boundaries of Germany. Others

criticize his era as culturally and politically conservative, which

sought to base the entire social and political make-up of West Germany

around the personal views of a single person, one who bore a certain

amount of mistrust towards his own people. His re-election campaign

centered around the slogan "No Experiments." As

chancellor, Adenauer tended to arrogate most major decisions to

himself, treating his ministers as mere extensions of his authority.

While this tendency has become somewhat less pronounced under

subsequent chancellors, Adenauer established the tradition of West

Germany (and later reunified Germany) as a "chancellor democracy." The

West German student movement of the late 1960s was essentially a

protest against the conservatism Adenauer had personified. Another

point of criticism was that Adenauer’s commitment to reconciliation

with France was in stark contrast to a certain indifference towards

Communist Poland. Like all other major West German political parties of

the time, the CDU refused to recognize the annexation of former German

territories given by the Soviets to Poland, and openly talked about

regaining these territories after strengthening West Germany’s position

in Europe. Adenauer’s achievements include the establishment of a stable democracy in defeated Germany, a lasting reconciliation with France, a general political reorientation towards the West, recovering limited

but far-reaching sovereignty for West Germany by firmly integrating the

country with the emerging Euro-Atlantic community (NATO and the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation). Adenauer is closely linked to the implementation of an enhanced pension system, which ensured unparalleled prosperity for retired persons. Along with his Minister for Economic Affairs and successor Ludwig Erhard, the West German model of a "social market economy" (a mixed economy with capitalism moderated by elements of social welfare and Catholic social teaching) allowed for the boom period known as the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic

miracle") that produced broad prosperity. Adenauer ensured a truly free

and democratic society which had been almost unknown to the German

people before — notwithstanding the attempt between 1919 and 1933

(the Weimar Republic) —

and which is today not just normal but also deeply integrated into

modern German society. He thereby laid the groundwork for Germany to

reenter the community of nations and to evolve as a dependable member

of the Western world. It can be argued that because of Adenauer’s

policies, a later reunification of both German states was possible; and

unified Germany has remained a solid partner in the European Union and NATO. In

retrospect, mainly positive assessments of his chancellorship prevail,

not only with the German public, which voted him the "greatest German

of all time" in a 2003 television poll, but

even with some of today’s left-wing intellectuals, who praise his

unconditional commitment to western-style democracy and European

integration. For all of his efforts as West Germany’s leader, Adenauer was named Time magazine’s Man of the Year in 1953. In 1954, he received the Karlspreis (English: Charlemagne Award), an Award by the German city of Aachen to people who contributed to the European idea, European cooperation and European peace. In

his last years in office Adenauer used to take a nap after lunch and,

when he was traveling abroad and had a public function to attend, he

sometimes asked for a bed in a room close to where he was supposed to

be speaking, so that he could rest briefly before he appeared. Adenauer found relaxation and great enjoyment in the Italian game of bocce and spent a great deal of his post political career playing this game. His favorite holiday place to do this was in Cadenabbia,

Italy, in a rented villa overlooking Lake Como, which has since been

acquired as a conference centre by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, the

German state-funded political foundation. When,

in 1967, after his death at the age of 91, Germans were asked what they

admired most about Adenauer, the majority responded that he had brought

home the last German prisoners of war from the USSR, which had become known as the “Return of the 10,000”. On 27 March 1952, a package addressed to Chancellor Adenauer exploded in the Munich Police

Headquarters, killing one Bavarian police officer. Two boys who had

been paid to send this package by mail had brought it to the attention

of the police. Investigations led to people closely related to the Herut Party and the former Irgun armed organization. The West German government kept all proof under seal in order to prevent antisemitic responses

from the German public. Five Israeli suspects identified by French and

German investigators were allowed to return to Israel. One of the participants, Eliezer Sudit, later revealed that the alleged mastermind behind this assassination attempt was Menachem Begin who would later become the Prime Minister of Israel. Begin had been the former commander of Irgun and at that time headed Herut and was a member of the Knesset. His goal was to put pressure on the German government and prevent the signing of the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany, which he vehemently opposed. David Ben-Gurion,

Prime Minister of Israel, appreciated Adenauer’s response in playing

down the affair and not pursuing it further, as it would have burdened

the relationship between the two new states. In June 2006 a slightly different version of this story appeared in one of Germany’s leading newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, quoted by The Guardian.

Begin had offered to sell his gold watch as the conspirators ran out of

money. The bomb was hidden in an encyclopedia and it killed a

bomb-disposal expert, injuring two others. Adenauer was targeted

because of the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany,

signed at that time, which was violently opposed by Begin. Sudit, the

story’s source, explained that the “intent was not to hit Adenauer but

to rouse the international media. It was clear to all of us there was

no chance the package would reach Adenauer.” The five conspirators were

arrested by the French police, in Paris. They “were [former] members of the ... Irgun” (the organisation had been disbanded in 1948, 4 years earlier).

In 1962, a scandal erupted when police under cabinet orders arrested five Der Spiegel journalists, charging them with high treason, specifically for publishing a memo detailing alleged weaknesses in the West German armed forces. The cabinet members, belonging to the Free Democratic Party, left their positions in November 1962, and Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss, himself the chairman of the Christian Social Union,

was dismissed, followed by the remaining Christian Democratic Union

cabinet members. Although Adenauer managed to remain in office for

almost another year, this scandal increased the pressure he was under

to fulfill his promise to resign before the end of the term, and he was

eventually succeeded as Chancellor by Ludwig Erhard in October 1963. He did remain chairman of the CDU until his resignation from that position in December 1966. Adenauer died on April 19, 1967 in his family home at Rhöndorf. According to his daughter, his last words were "Da jitt et nix zo kriesche!" (Cologne dialect for "There's nothin' to weep about!") Konrad Adenauer's state funeral in Cologne Cathedral was attended by a large number of world leaders, among them United States President Lyndon B. Johnson. After the Requiem Mass and service, his remains were brought upstream to Rhöndorf on the Rhine aboard Kondor, with Seeadler and Sperber as escorts, three Jaguar class fast attack craft of the German Navy, "past the thousands who stood in silence on both banks of the river." He is interred at the Waldfriedhof [Forest Cemetery] at Rhöndorf.