<Back to Index>

- Archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, 1822

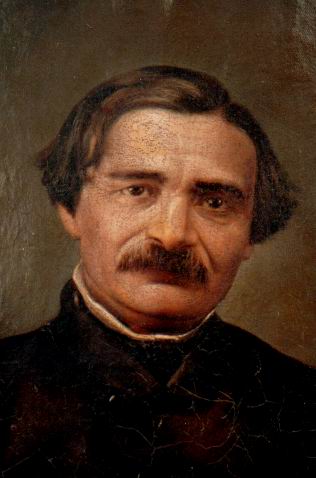

- Author Ion Heliade Rădulescu, 1802

- Prime Minister of Spain Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, 1st Count-Duke of Olivares, 1587

PAGE SPONSOR

Ion Heliade Rădulescu or Ion Heliade (also known as Eliad or Eliade Rădulescu; January 6, 1802 – April 27, 1872) was a Wallachian-born Romanian academic, Romantic and Classicist poet, essayist, memoirist, short story writer, newspaper editor and politician. A prolific translator of foreign literature into Romanian, he was also the author of books on linguistics and history. For much of his life, Heliade Rădulescu was a teacher at Saint Sava College in Bucharest, which he helped reopen. He was a founding member and first president of the Romanian Academy.

Heliade Rădulescu is considered one of the foremost champions of Romanian culture from the first half of the 19th century, having first risen to prominence through his association with Gheorghe Lazăr and his support of Lazăr's drive for discontinuing education in Greek.

Over the following decades, he had a major role in shaping the modern

Romanian language, but caused controversy when he advocated the massive

introduction of Italian neologisms into the Romanian lexis. A Romantic nationalist landowner siding with moderate liberals, Heliade was among the leaders of the 1848 Wallachian revolution, after which he was forced to spend several years in exile. Adopting an original form of conservatism, which emphasized the role of the aristocratic boyars in Romanian history, he was rewarded for supporting the Ottoman Empire and clashed with the radical wing of the 1848 revolutionaries. Heliade Rădulescu was born in Târgovişte,

the son of Ilie Rădulescu, a wealthy proprietor who served as the

leader of a patrol unit during the 1810s, and Eufrosina Danielopol, who

had been educated in Greek. Three of his siblings died of bubonic plague before 1829. Throughout

his early youth, Ion was the focus of his parents' affectionate

supervision: early on, Ilie Rădulescu purchased a house once owned by

the scholar Gheorghe Lazăr on the outskirts of Bucharest (near Obor), as a gift for his son. At the time, the Rădulescus were owners of a large garden in the Bucharest area, nearby Herăstrău, as well as of estates in the vicinity of Făgăraş and Gârbovi. After basic education in Greek with a tutor known as Alexe, Ion Heliade Rădulescu taught himself reading in Romanian Cyrillic (reportedly by studying the Alexander Romance with the help of his father's Oltenian servants). He

subsequently became an avid reader of popular novels, especially during

his 1813 sojourn in Gârbovi (where he had been sent after other

areas of the country came to be ravaged by Caragea's plague). After 1813, the teenaged Rădulescu was a pupil of the Orthodox monk Naum Râmniceanu; in 1815, he moved on to the Greek school at Schitu Măgureanu, in Bucharest, and, in 1818, to the Saint Sava School, where he studied under Gheorghe Lazăr's supervision.

Between his 1820 graduation and 1821, when effects of the Wallachian uprising led to the School ceasing its activities, he was kept as Lazăr's assistant teacher, tutoring in arithmetics and geometry. It was during those years that he adopted the surname Heliade (also rendered Heliad, Eliad or Eliade), which, he later explained, was a Greek version of his patronymic, in turn stemming from the Romanian version of Elijah. In

1822, after Gheorghe Lazăr had fallen ill, Heliade reopened Saint Sava

and served as its main teacher (initially, without any form of

remuneration). He was later joined in this effort by other intellectuals of the day, such as Eufrosin Poteca, and, eventually, also opened an art class overseen by the Croat Carol Valştain. This re-establishment came as a result of ordinances issued by Prince Grigore IV Ghica, who had just been assigned by the Ottoman Empire to the throne of Wallachia upon the disestablishment of Phanariote rule, encouraging the marginalization of ethnic Greeks who had assumed public office in previous decades. Thus, Prince Ghica had endorsed education in Romanian and, in one of his official firmans, defined teaching in Greek as "the foundation of evils" (temelia răutăţilor). During the late 1820s, Heliade became involved in cultural policies. In 1827, he and Dinicu Golescu founded Soţietatea literară românească (the

Romanian Literary Society), which, through its program (mapped out by

Heliade himself), proposed Saint Sava's transformation into a college, the opening of another such institution in Craiova, and the creation of schools in virtually all Wallachian localities. In addition, Soţietatea attempted to encourage the establishment of Romanian-language newspapers, calling for an end to the state monopoly on printing presses. The grouping, headquartered on central Bucharest's Podul Mogoşoaiei, benefited from Golescu's experience abroad, and was soon joined by two future Princes, Gheorghe Bibescu and Barbu Dimitrie Ştirbei. Its character was based on Freemasonry; around that time, Heliade is known to have become a Freemason, as did a large section of his generation. In 1828, Heliade published his first work, an essay on Romanian grammar, in the Transylvanian city of Hermannstadt (which was part of the Austrian Empire at the time), and, on April 20, 1829, began printing the Bucharest-based paper Curierul Românesc. This was the most successful of several attempts to create a local newspaper, something Golescu first attempted in 1828. Publishing articles in both Romanian and French, Curierul Românesc had, starting in 1836, its own literary supplement, under the title of Curier de Ambe Sexe; in print until 1847, it notably published one of Heliade's most famous poems, Zburătorul. Curierul Românesc was

edited as a weekly, and later as a bimonthly, until 1839, when it began

to be issued three or four times a week. Its best-known contributors

were Heliade himself, Grigore Alexandrescu, Costache Negruzzi, Dimitrie Bolintineanu, Ioan Catina, Vasile Cârlova, and Iancu Văcărescu. In 1823, Heliade met Maria Alexandrescu, with whom he fell passionately in love, and whom he later married. By

1830, the Heliades' two children, a son named Virgiliu and a daughter

named Virgilia, died in infancy; subsequently, their marriage entered a

long period of crisis, marked by Maria's frequent outbursts of jealousy. Ion Heliade probably had a number of extramarital affairs: a Wallachian Militia officer named Zalic, who became known during the 1840s, is thought by some, including the literary critic George Călinescu, to have been the writer's illegitimate son. Before

the death of her first child, Maria Heliade welcomed into her house

Grigore Alexandrescu, himself a celebrated writer, whom Ion suspected

had become her lover. Consequently,

the two authors became bitter rivals: Ion Heliade referred to

Alexandrescu as "that ingrate", and, in an 1838 letter to George Bariţ, downplayed his poetry and character (believing that, in one of his fables, Alexandrescu had depicted himself as a nightingale, he commented that, in reality, he was "a piteous rook dressed in foreign feathers"). Despite these household conflicts, Maria Heliade gave birth to five other children, four daughters and one son (Ion, born 1846). In

October 1830, together with his uncle Nicolae Rădulescu, he opened the

first privately-owned printing press in his country, operating on his

property at Cişmeaua Mavrogheni, in Obor (the land went by the name of Câmpul lui Eliad — "Eliad's Field", and housed several other large buildings). Among the first works he published was a collection of poems by Alphonse de Lamartine, translated by Heliade from French, and grouped together with some of his own poems. Later, he translated a textbook on meter and Louis-Benjamin Francoeur's standard manual of Arithmetics, as well as works by Enlightenment authors — Voltaire's Mahomet, ou le fanatisme, and stories by Jean-François Marmontel. They were followed, in 1839, by a version of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Julie, or the New Heloise. Heliade began a career as a civil servant after the Postelnicie commissioned him to print the Official Bulletin, and later climbed through the official hierarchy, eventually serving as Clucer. This rise coincided with the establishment of the Regulamentul Organic regime, inaugurated, upon the end of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828 – 1829, by a Imperial Russian administration under Pavel Kiselyov. When Kiselyov placed an order with Heliade for the printing of official documents, including the Regulament,

the writer and his family were made prosperous by the sales.

Nevertheless, Heliade maintained contacts with the faction of reformist boyars: in 1833, together with Ion Câmpineanu, Iancu Văcărescu, Ioan Voinescu II, Constantin Aristia, Ştefan and Nicolae Golescu, as well as others, he founded the short-lived Soţietatea Filarmonică (the Philharmonic Society), which advanced a cultural agenda (and was especially active in raising funds for the National Theater of Wallachia). Aside from its stated cultural goals, Soţietatea Filarmonică continued a covert political activity. In 1834, when Prince Alexandru II Ghica came to the throne, Heliade became one of his close collaborators, styling himself "court poet". Several of the poems and discourses he authored during the period are written as panegyrics, and dedicated to Ghica, whom Heliade depicted as an ideal prototype of a monarch. As

young reformists came into conflict with the prince, he kept his

neutrality, arguing that all sides involved represented a privileged

minority, and that the disturbances were equivalent to "the quarrel of

wolves and the noise made by those in higher positions over the

torn-apart animal that is the peasant". He was notably critical of the radical Mitică Filipescu, whom he satirized in the poem Căderea dracilor ("The Demons' Fall"), and later defined his own position with the words "I hate tyrants. I fear anarchy". It was also in 1834 that Heliade began teaching at the Soţietatea Filarmonică's school (alongside Aristia and the musician Ioan Andrei Wachmann), and published his first translations from Lord Byron (in 1847, he completed the translation of Byron's Don Juan). The next year, he began printing Gazeta Teatrului Naţional (official voice of the National Theater, published until 1836), and translated Molière's Amphitryon into Romanian. In 1839, Heliade also translated Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote from a French source. The first collection of his own prose and poetry works saw print in 1836. Interested in the development of local art, he contributed a brochure on

drawing and architecture in 1837, and, during the same year, opened the

first permanent exhibit in Wallachia (featuring copies of Western

paintings, portraits, and gypsum casts of various known sculptures). By the early 1840s, Heliade began expanding on his notion that modern Romanian needed to emphasize its connections with other Romance languages through neologisms from Italian, and, to this goal, he published Paralelism între limba română şi italiană ("Parallelism between the Romanian language and Italian", 1840) and Paralelism între dialectele român şi italian sau forma ori gramatica acestor două dialecte ("Parallelism between the Romanian and Italian Dialects or the Form or Grammar of These Two Dialects", 1841). The two books were followed by a compendium, Prescurtare de gramatica limbei româno-italiene ("Summary of the Grammar of the Romanian-Italian Language"), and, in 1847, by a

comprehensive list of Romanian words that had originated in Slavic, Greek, Ottoman Turkish, Hungarian, and German (Romanian lexis). By

1846, he was planning to begin work on a "universal library", which was

to include, among other books, the major the philosophical writings of,

among others, Plato, Aristotle, Roger Bacon, René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Before Alexandru Ghica was replaced with Gheorghe Bibescu, his relations with Heliade had soured. In contrast with his earlier call for moderation, the writer decided to side with the liberal current in its conspiratorial opposition to Bibescu. The

so-called "Trandafiloff affair" of early 1844 was essential in this

process — it was provoked by Bibescu's decision to lease all Wallachian

mines to a Russian engineer named Alexander Trandafiloff, a measure considered illegal by the Assembly and ultimately ending in Bibescu's decision to dissolve his legislative. These events made Heliade publish a pamphlet titled Măceşul ("The Eglantine"), which was heavily critical of Russian influence and reportedly sold over 30,000 copies. It was centered on the pun alluding to Trandafiloff's name — trandafir cu of în coadă (lit. "a rose ending in -of", but also "a rose with grief for a stem"). Making additional covert reference to Trandafiloff as "the eglantine", it featured the lyrics: Măi măceşe, măi măceşe, Eglantine, o eglantine, In spring 1848, when the first European revolutions had erupted, Heliade was attracted into cooperation with Frăţia, a secret society founded by Nicolae Bălcescu, Ion Ghica, Christian Tell, and Alexandru G. Golescu, and sat on its leadership committee. He also collaborated with the reform-minded French teacher Jean Alexandre Vaillant, who was ultimately expelled after his activities were brought to the attention of authorities. On April 19, 1848, following financial setbacks, Curierul Românesc ceased printing (this prompted Heliade to write Cântecul ursului, "The Bear's Song", a piece ridiculing his political enemies). Heliade progressively distanced himself from the more radical groups, especially after discussions began on the issue of land reform and the disestablishment of the boyar class. Initially, he accepted the reforms, and, after the matter was debated within Frăţia just before rebellion broke out, he issued a resolution acknowledging this (the document was probably inspired by Nicolae Bălcescu). The compromise also set other goals, including national independence, responsible government, civil rights and equality, universal taxation, a larger Assembly, five-year terms of office for Princes (and their election by the National Assembly), freedom of the press, and decentralization. On June 21, 1848, present in Islaz alongside Tell and the Orthodox priest known as Popa Şapcă, he read out these goals to a cheering crowd, in what was to be the effective start of the uprising (Proclamation of Islaz). Four

days after the Islaz events, the revolution succeeded in toppling

Bibescu, whom it replaced with a Provisional Government which

immediately attracted Russian hostility. Presided over by Metropolitan Neofit, it included Heliade, who was also Minister of Education, as well as Tell, Ştefan Golescu, Gheorghe Magheru, and, for a short while, the Bucharest merchant Gheorghe Scurti. Disputes regarding the shape of land reform continued, and in late July, the Government created Comisia proprietăţii (the Commission on Property), representing both peasants and landlords and overseen by Alexandru Racoviţă and Ion Ionescu de la Brad. It

too failed to reach a compromise over the amount of land to be

allocated to peasants, and it was ultimately recalled by Heliade, who

indicated that the matter was to be deliberated once a new Assembly had

been voted into office. In time, the writer adopted a conservative outlook in respect to boyar tradition, developing a singular view of Romanian history around the issues of property and rank in Wallachia. In the words of historian Nicolae Iorga: "Eliad had wanted to lead, as dictator, this movement that added liberal institutions to the old society that had been almost completely maintained in place". Like most other revolutionaries, Heliade favored maintaining good relations with the Ottoman Empire, Wallachia's suzerain power, hoping that this policy could help counter Russian pressures. As Sultan Abdülmecid was assessing the situation, Süleyman Paşa was

dispatched to Bucharest, where he advised the revolutionaries to carry

on with their diplomatic efforts, and ordered the Provisional Government to be replaced by Locotenenţa domnească, a triumvirate of regents comprising Heliade, Tell, and Nicolae Golescu. Nonetheless,

the Ottomans were pressured by Russia into joining a clampdown on

revolutionary forces, which resulted, during September, in the

reestablishment of Regulamentul Organic and its system of government. Together with Tell, Heliade sought refuge at the British consulate in Bucharest, where they were hosted by Robert Gilmour Colquhoun in exchange for a deposit of Austrian florins. Leaving his family behind, he was allowed to pass into the Austrian-ruled Banat, before moving into self-exile in France while his wife and children were sent to Ottoman lands. In 1850 – 1851, several of his memoirs of the revolution, written in both Romanian and French, were published in Paris, the city were he had taken residence. He shared his exile with Tell and Magheru, as well as with Nicolae Rusu Locusteanu. It was during his time in Paris that he met with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the anarchist philosopher who had come to advance a moderate project around small-scale property (to counter both economic liberalism and socialism). Heliade used this opportunity to make the Romanian cause known to the staff of Proudhon's La Voix de Peuple. Major French publications to which he contributed included La Presse, La Semaine, and Le Siècle, where he also helped publicize political issues pertaining to his native land. Heliade was credited with having exercised influence over historian Élias Regnault; Nicolae Iorga argued that Regnault's discarded his own arguments in favor of a unified Romanian state to include Transylvania (a

concept which Heliade had come to resent), as well amending his earlier

account of the 1848 events, after being exposed to "Eliad's propaganda". While claiming to represent the entire body of Wallachian émigrés, Heliade had by then grown disappointed with the political developments, and, in his private correspondence, commented that Romanians in

general were "idle", "womanizing", as well as having "the petty and

base envies of women", and argued that they required "supervision [and]

leadership". His

fortune was declining, especially after pressures began for him to pay

his many debts, and he often lacked the funds for basic necessities. At the time, he continuously clashed with other former revolutionaries, including Bălcescu, C.A. Rosetti, and the Golescus, who resented his ambiguous stance in respect to reforms, and especially his willingness to accept Regulamentul Organic as an instrument of power; Heliade issued the first in a series of pamphlets condemning young radicals, contributing to factionalism inside the émigré camp. His friendship with Tell also soured, after Heliade began speculating that the revolutionary general was committing adultery with Maria. In 1851, Heliade reunited with his family on the island of Chios, where they stayed until 1854. Following the evacuation of Russian troops from the Danubian Principalities during the Crimean War, Heliade was appointed by the Porte to represent the Romanian nation in Shumen, as part of Omar Pasha's staff. Again expressing sympathy for the Ottoman cause, he was rewarded with the title of Bey. According to Iorga, Heliade's attitudes reflected his hope of "recovering the power lost" in 1848; the historian also stressed that Omar never actually made use of Heliade's services. Later

in the same year, he decided to return to Bucharest, but his stay was

cut short when the Austrian authorities, who, under the leadership of Johann Coronini-Cronberg, had taken over administration of the country as a neutral force, asked for him to be expelled. Returning to Paris, Heliade continued to publish works on political and cultural issues, including an analysis of the European situation after the Peace Treaty of 1856 and an 1858 essay on the Bible. In 1859, he published his own translation of the Septuagint, under the name Biblia sacră ce cuprinde Noul şi Vechiul Testament ("The Holy Bible, Comprising the New and Old Testament"). As former revolutionaries, grouped in the Partida Naţională faction, advanced the idea of union between Wallachia and Moldavia in election for the ad-hoc Divan, Heliade opted not to endorse any particular candidate, while rejecting outright the candidature of former prince Alexandru II Ghica (in

a private letter, he stated: "let them elect whomever [of the

candidates for the throne], for he would still have the heart of a man

and some principles of a Romanian; only don't let that creature [Ghica]

be elected, for he is capable of going to the dogs with this country"). Later

in 1859, Heliade returned to Bucharest, which had become the capital of

the United Principalities after the common election of Alexander John Cuza and later that of an internationally-recognized Principality of Romania. It was during that period that he again added Rădulescu to his surname. Until

his death, he published influential volumes on a variety of issues,

while concentrating on contributions to history and literary criticism,

and editing a new collection of his own poems. In 1863, Domnitor Cuza awarded him an annual pension of 2,000 lei. One year after the creation of the Romanian Academy (under the name of "Academic Society"), he was elected its first President (1867), serving until his death. In 1869, Heliade and Alexandru Papiu-Ilarian successfully proposed the Italian diplomat and philologist Giovenale Vegezzi-Ruscalla as honorary member of the Academy. By

then, like most other 1848 Romantics, he had become the target of

criticism from the younger generation of intellectuals, represented by

the Iaşi-based literary society Junimea; in 1865, during one of its early public sessions, Junimea explicitly rejected works by Heliade and Iancu Văcărescu. During the elections of 1866, Heliade Rădulescu won a seat in the Chamber as a deputy for the city of Târgovişte. As Cuza had been ousted from power by a coalition of political groupings, he was the only Wallachian deputy to join Nicolae Ionescu and other disciples of Simion Bărnuţiu in opposing the appointment of Carol of Hohenzollern as Domnitor and a proclamation stressing the perpetuity of the Moldo-Wallachian union. Speaking in Parliament, he likened the adoption of foreign rule to the Phanariote period. The opposition was nevertheless weak, and the resolution was passed with a large majority. Among Ion Heliade Rădulescu's last printed works were a textbook on poetics (1868) and a volume on Romanian orthography. By that time, he had come to consider himself a prophet-like figure, and the redeemer of his motherland, notably blessing his friends with the words "Christ and Magdalene be with you!" His mental health declining, he died at his Bucharest residence on Polonă Street, nr. 20. Heliade Rădulescu's grandiose funeral ceremony attracted a large number of his admirers; the coffin was buried in the courtyard of the Mavrogheni Church.

[…]

Dă-ne pace şi te cară,

Du-te dracului din ţară.

[…]

Leave us in peace and go away,

Get the hell out of the country.