<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Sofia Vasilyevna Kovalevskaya, 1850

- Playwright Jean Baptiste Poquelin (Molière), 1622

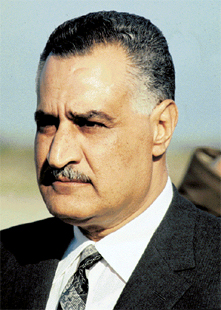

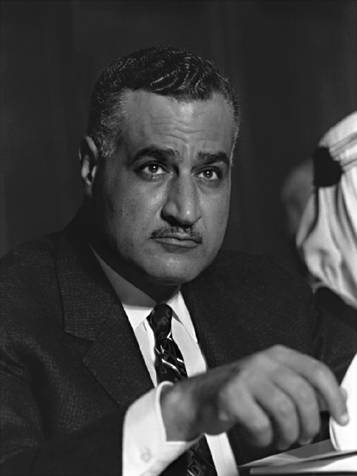

- 2nd President of Egypt Gamal Abdel Nasser, 1918

PAGE SPONSOR

Gamal Abdel Nasser (Arabic: جمال عبد الناصر; 15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was the second President of Egypt from 1954 until his death. He led the bloodless coup which toppled the monarchy of King Farouk and heralded a new period of modernization and socialist reform in Egypt together with a profound advancement of pan-Arab nationalism.

Nasser is seen as one of the most important political figures in both modern Arab history and Third World politics in the 20th century. Although he was originally met with suspicion after putting the country's new president, Muhammad Naguib, under house arrest in 1954, he soon gained immense popularity in Egypt and the Arab world when he nationalized the Suez Canal from

its British and French stockholders two years later. The consequent

British, French, and Israeli invasion of and withdrawal from the canal

zone installed Nasser as the decisive victor in the eyes of his people.

Meanwhile, he had commenced work on the major projects of the Aswan High Dam in Upper Egypt and the Helwan steelworks. Through his actions and the charisma of his speeches, Nasser's version of pan-Arabism, also referred to as Nasserism, won a great following in the Arab world. By 1958, he united his country with Syria, forming the short-lived United Arab Republic (UAR). At the same time, he inspired successful and unsuccessful revolutions in several Arab countries. This

period of glory for Nasser quickly dissipated, and three years after

the founding of the union, Syria split from the UAR. Afterward, he

concentrated on pursuing increased socialist and modernizing measures

in Egypt, which included the nationalization of more companies,

reforming the al-Azhar Mosque,

providing housing and universal health care, and other liberalization

schemes. His commanding position among the Arab leaders was also

re-established in the wake of Nasserist-led coups and revolutions in

Algeria, Iraq, Syria, and North Yemen. The latter dragged him into war

in North Yemen as he sent thousands of Egyptian troops to defend the

new anti-royalist government. Nasser's status as "leader of the Arabs"

was severely tarnished as a result of the Israeli victory over the Arab

armies in the Six Day War of

1967, yet many in the general Arab populace still viewed him as a

symbol of their dignity and freedom; when he declared his resignation

soon after, tens of thousands of Egyptians immediately protested,

prompting him to retract his decision. After 1967, Nasser commenced the War of Attrition with

Israel and his strategy of playing the world superpowers — the US and the

USSR — against each other ceased as he developed closer relations with

the latter. On September 28, 1970, Nasser died of a heart attack following the conclusion of an emergency Arab League summit he had organized to end the civil war between Palestinian paramilitaries and the Jordanian Army. His funeral procession in Cairo drew

five million mourners as many others mourned throughout the Arab world.

His mixed legacy has been debated until the present day. Time magazine

wrote that despite the mistakes and setbacks of his career, the

elevation of dignity and pride Nasser instilled in Egyptians and Arabs

everywhere "may have been enough to balance his flaws and failures." Gamal's father, Abdel Nasser Hussein, was born on 11 July 1888 in Beni Mur, a village near the city of Asyut in southern Egypt, to Hussein Khalil Sultan. Abdel Nasser Hussein had six brothers and one sister. Hussein Sultan's in-laws emigrated to Alexandria and in March 1904 Abdel Nasser was sent with them to attended al-Najah al-Ahlya elementary school in Alexandria. At

the time, it was only required to have a Primary Education Certificate

to work in the civil service. Abdel Nasser received his certificate in

1909 and joined the postal service soon after. In 1917 he married Fahima, the daughter of Mohammad Hamad, a coal merchant and contractor originally from Mallawi, Minya. According to biographer Robert Stephens, the inhabitants of Beni Mur belonged to an Arab tribe that hailed from the Hejaz — the western part of the Arabian Peninsula.

Stephens said Nasser's family had tribal inclinations and a sense of

personal loyalty, differing from that of most Egyptians. Gamal Abdel

Nasser's daughter, Hoda, said she was not informed of her family's

lineage, but suspects the claim of its Arabian descent to be accurate.

In addition, Gamal's biographers wrote that his family believed

strongly in the "Arab notion of glory," citing

the naming of Gamal's brother, Izz al-Arab ("Glory of the Arabs"); the

name is a rare occurrence in Egypt, as well as other parts of the Arab

world.

Gamal Abdel Nasser was born on 15 January 1918 in the suburb of Bakos, Alexandria, Egypt. He was the first son of Fahima and Abdel Nasser and was later followed by two brothers, Izz al-Arab and al-Leithi. Due to his father's work, the family traveled frequently. In 1921, they moved to Asyut and later in 1923 to Khatatba,

where Abdel Nasser Hussein ran a post office. Gamal attended a primary

school for the children of railway employees until he was sent in 1924

to live with his paternal uncle, Khalil Hussein, in Cairo, and attend

the Nahhasin elementary school. Gamal

exchanged letters with his mother and visited her on holidays. He

stopped receiving messages at the end of April 1926. When Gamal

returned to Khatatba, he learned that his mother had died after giving

birth to his third brother Shawki and his family had kept it from him. According

to most of his biographers, Nasser adored his mother and the injury of

her death deepened when his father remarried before the year ended. Nasser

went to Alexandria in 1928 to live with his maternal grandfather,

Muhammad Hammad, while attending Attarin elementary school. There, Gamal joined a demonstration even though he was not aware of its purpose. He did not do well in school and in 1929 transferred back to Cairo. His

uncle Khalil left Cairo soon after and Gamal's father was posted to

Suez, where there was no suitable school for Gamal. Therefore, he was

sent to a private boarding school in Helwan for

a year. In 1933 Khalil returned to Cairo and Gamal was sent to live

with him. The following year Gamal went to Alexandria to live with his

maternal grandparents, where he received a secondary education

certificate from a private school. Abdel Nasser was posted to Cairo and

Gamal joined his family there. He attended Al Nahda al Masria school

and received his leaving certificate in 1936. On 12 November 1935, Nasser was wounded during an anti-British demonstration, in which several students tried to cross el-Roda Bridge in Cairo to clash with the police. Afterward, he was arrested and detained for two days along with several members of the Egyptian Socialist Party. The wound he sustained was superficial, but it won him mention in the nationalistic newspaper Al Gihad. Nasser's

political involvement lasted throughout his school career, and became

such a dominant part of his life that during his last year of secondary

school, Nasser only attended for 45 days. During

that same period, 1935–36, Nasser was elected chairman of a committee

of Cairo secondary school students interested in Egyptian political

reform. According to American-Palestinian journalist Said Aburish,

the combination of living in so many cities and attending different

schools did not distress Nasser, but broadened his horizons, allowing

him to become aware of the class divisions in Egyptian society. Despite

constantly changing schools, Nasser spent most of his spare time

reading, particularly in 1933 when his uncle happened to live near the National Library of Egypt. In addition to the Qur'an, the sayings of Muhammad, and the lives of the Sahaba (Muhammad's companions), he read the works of Napoleon, Gandhi, Voltaire, Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens, and many others. He was greatly influenced by the anti-British politician Mustafa Kamel and the nationalist poet Ahmed Shawqi. Nasser married Tahia Kazim, the 22-year old daughter of a well-off Iranian tea

merchant and Egyptian mother, in 1944. Tahia's parents had died in her

early life and she was introduced to Nasser through her brother Abdel

Hamid Kazim, a merchant friend of Nasser's, in 1943. After

their wedding, the couple moved into a house in Manshiyat al-Bakri, a

suburb of Cairo, where they would live for the rest of their lives. His

entry in 1937 into the officer corps secured him relatively well-paid

employment in a society where most people lived in poverty. Nasser was

still well below the wealthy Egyptian elite, however, and continued his

resentment of those born into wealth and power. Throughout

his life, Nasser did his best to keep his career separate from his

family life. Although he and Tahia would sometimes discuss politics at

home, he preferred to spend as much of his free time as possible with

his children. Nasser and Tahia had two daughters and three sons, Hoda, Mona, Khaled, Abdel Hamid and Abdel Hakim. Nasser's eldest daughter, Hoda, became a researcher in politics and a professor of political science in Cairo University.

With her help, various rare documents regarding the 1952 Egyptian

Revolution and her father's career have been gathered, documented and

displayed at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina as well as on the internet. Khaled

became a member of the leftist organization known as the "Egypt

Revolution". In 1988, Egyptian authorities charged him with organizing

and financing the killing of two Israeli officials. Mona was married to Egyptian businessman Ashraf Marwan until his death in 2007. They bore two sons. In March 1937, Nasser applied for entry to the Abassia Military Academy, temporarily abandoning his political activities in favor of studying to become an army officer. He lacked a wasta — an

influential intermediary to promote his application against many

others — and was turned down. Disappointed, he enrolled in law school,

but failed and then attempted to enter the police academy where he

again was unsuccessful because he did not have a wasta. Convinced that he needed a wasta,

Nasser managed to see the secretary of state, Ibrahim Kheiry Pasha, who

sponsored his second attempt into the military academy. From then on,

with little contact with his family, he focused on his military career.

It was at the academy that he met Abdel Hakim Amer and Anwar Sadat, two of his important aides during his presidency. After passing his final exam at Abassia, he was posted to the town of Mankabad, near his native Beni Mur, and was commissioned as 2nd lieutenant in the infantry. In 1939, Nasser and Amer volunteered to serve in Sudan (which was united with Egypt at the time) where they arrived shortly before the outbreak of World War II. Aburish states, however, that he and Amer were posted to the Sudan in 1941. During the war, Nasser and Sadat established contact with agents of the Axis powers, particularly several Italians, and planned a coup to coincide with an Italian offensive that would expel the British forces from Egypt. The plan, however, was never executed. After

briefly returning to Egypt, Nasser went back to the Sudan in September

1942, then secured a job as an instructor in the Abassia academy in May

1943. In 1942, the Egyptian prime minister, Ali Maher, was suspected of having pro-Axis sympathies at the time when Erwin Rommel was leading the Afrika Korps into Egypt. Lord Lampson, the British High-Commissioner of Egypt, backed by a battalion of British troops, marched into King Farouk's palace and ordered him to dismiss Maher and appoint the pro-British Mustafa el-Nahhas in

his place. Nasser, like most Egyptians, saw this as a blatant violation

of Egyptian sovereignty and wrote "I am ashamed that our army has not

reacted against this attack." He said further that he prayed to Allah for "a calamity to overtake the English." Nasser

also began forming a group consisting of other young military officers

with strong nationalist feelings and who supported some form of

revolution. Mainly

through Amer, Nasser stayed in touch with the members of the group.

Meanwhile, Amer continued to discover interested officers within the

various branches of the Egyptian Armed Forces and presented a full file on each of them to Nasser. As Egypt remained officially neutral until long after the Axis defeat at the Battle of el-Alamein, the Egyptian military did not participate in the war. Nasser's first experience on the battlefield was in Palestine during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Prior to the arrival of Arab armies to Palestine, many paramilitary groups in the Arab world, including the Muslim Brotherhood and the Arab Liberation Army (ALA),

volunteered to participate. Because of Nasser's doubts about the former

and his lack of respect for the governments who sponsored the ALA, he

offered his services to the Arab Higher Committee led by Amin al-Husayni, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem.

He met with al-Husayni, who was impressed by him, at his office in

Cairo. The Egyptian government refused to allow Nasser to join

al-Husayni's forces, however, much to the Nasser's disappointment. In May 1948, after the end of the mandate and British withdrawal, King Farouk sent the Egyptian army into Palestine. Nasser served in the 6th Infantry Battalion. During the war, he wrote of the unpreparedness of the army, saying "our soldiers were dashed against fortifications." Nasser was deputy commander of the Egyptian forces that secured the area known as the Falluja Pocket. By August 1948, his brigade was surrounded by the Israeli Army and appeals for help from Jordan's Arab Legion went unheeded. Nonetheless, Nasser refused to surrender, but negotiations between Israel and Egypt resulted in the ceding of Falluja to Israel. In February 1949, Nasser was sent as a member of the Egyptian delegation to Rhodes to negotiate a formal ceasefire with Israel, and reportedly considered the terms humiliating. After the war, he gained a post as an instructor at the Royal Military Academy in Cairo. He

sent emissaries to forge an alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood in

October 1948, but soon concluded that the agenda of the Brotherhood was

not a nationalist one like his. From then on, he would take measures

protecting his activities from the influence of their organization. Upon

returning to Egypt, Nasser was summoned and interrogated by Prime

Minister Ibrahim Abdel Hadi who suspected he was forming a secret group

of dissenting officers, an allegation which he "convincingly" had

denied. After 1949, this group adopted the name "Association of Free Officers" and "talked of... freedom and the restoration of their country’s dignity." He

organized the founding committee of the Free Officers which eventually

comprised fourteen men from different political backgrounds, with some

being members of Young Egypt,

the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Egyptian Communist Party, as well as

the aristocracy. Nasser was unanimously elected chairman of the

organization. In the 1950 parliamentary elections, the Wafd party

of el-Nahhas gained a victory — mostly due to the absence of the Muslim

Brotherhood who boycotted the elections — and posed a threat to the Free

Officers because they had campaigned for demands similar to theirs. A

number of corruption accusations against the Wafd politicians began to

surface, however, breeding an atmosphere of rumor and suspicion that

consequently brought the Free Officers to the forefront of Egyptian

politics. By then, the organization expanded to around ninety members;

according to one member, Khaled Mohieddine, "nobody knew all of them and where they belonged in the hierarchy except Nasser." Nasser

felt that the Free Officers were not ready to move against the

government and for nearly two years he did little beyond recruit more

officers and issue his underground news bulletins. After the Wafd government abrogated the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty,

on 11 October 1951 — which had given the British control over the Suez

Canal until 1956 — the popularity of this move as well as that of the

government-sponsored forces who volunteered to launch guerrilla attacks

against the British, put pressure on Nasser to act. According to Sadat,

Nasser decided to wage "a large scale assassination campaign." In January 1952, he and a number of unidentified officers attempted to kill the royalist general Hussein Sirri Pasha by

firing their submachine guns at his car while he drove through Cairo's

streets. Instead, an innocent woman passerby was wounded in the

incident and apparently began to shriek and wail. Nasser recalled that

her wails "haunted" him and dissuaded him against similar action in the

future. Sirri

was very close to Farouk and was nominated for the presidency of the

Officer's Club — a normally ceremonial office — with his backing. Nasser

was determined to establish the independence of the army from the

monarchy and with Amer as an intermediary, decided to field a nominee

for the Free Officers; they selected Muhammad Naguib, a popular general who offered his resignation to Farouk in 1942 and was

thrice wounded in the Palestine War. Naguib won overwhelmingly and the

Free Officers, through their connection with a leading Egyptian daily, al-Misri, publicized his victory and praised the nationalistic spirit of the army. On 25 January 1952, the British forces posted along the Suez Canal had a major confrontation with the police force of Ismailia,

resulting in the deaths of forty Egyptian policemen. The next day,

protesting mobs in the thousands roamed the streets of Cairo attacking

foreign and pro-British Egyptian establishments which resulted in the

deaths of 76 people, including 9 British subjects. Afterward, Nasser

and Khaled Mohieddine published a simple six-point program for Egypt,

condemning British influence in the country. A short time later, in May

1952, Nasser received word that Farouk knew the names of the Free

Officers and intended to arrest them. Thus, he immediately entrusted Zakaria Mohieddine with the task of drawing up plans for the takeover of the government by army units loyal to the association. The

Free Officers did not intend to install themselves in the government,

but to reestablish a parliamentary democracy. Nasser did not believe

that a low-ranking general like himself (a lieutenant-colonel) would be

accepted by the Egyptian people and so he selected Naguib, a general,

to be his "boss" and lead the coup. The revolution they

had long sought was launched on 22 July and was declared a success the

next day. The Free Officers seized control of all government buildings,

radio stations, police stations, and the army headquarters in Cairo.

The coup installed Naguib as President of Egypt.

While many of the officers were leading their units, Nasser donned

civilian clothing to avoid detection by royalists and moved around

Cairo to monitor the situation. In a move to prevent foreign intervention in the coup, two days before the revolution, Nasser notified the United States and Britain, both of which agreed not to aid Farouk. Nasser

and his fellow revolutionaries also gave in to American pressure by

allowing the deposed king and his family to "leave Egypt unharmed and

'with honour' ". According

to Aburish, after assuming power, Nasser and the Free Officers expected

to become the "guardians of the people's interests" against the

monarchy and the pasha-class, while leaving the day-to-day tasks of government to civilians. Thus,

they asked Ali Maher, a former prime minister, to accept being

reappointed his previous position and form an all-civilian cabinet. The Free Officers then renamed themselves the Egyptian Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), with Naguib as chairman and Nasser as vice-chairman. The

relationship between the RCC and Maher grew tense, however, with the

latter viewing Nasser's schemes to be too radical, culminating in

Maher's resignation on September 7. The reforms Nasser pursued were

agrarian reform, the abolition of the monarchy, and the reorganization

of political parties. Afterward, Naguib assumed the additional role of prime minister and Nasser that of deputy prime minister and interior minister. In September, the Agrarian Reform Law was put into effect. For Nasser, the law gave the RCC its own identity and transformed the coup into a revolution. Preceding the reform law, in August 1952, Communist-led riots broke out at textile factories in Kafr el-Dawwar leading

to a confrontation with the army that left nine people dead. Most of

the RCC, including Naguib, insisted on making an example of the riot's

two ringleaders by executing them, but Nasser firmly opposed this.

Nonetheless, the sentences were carried out. The Muslim Brotherhood

supported the RCC and after Naguib's assumption of power, they demanded

four ministerial portfolios in the new cabinet, but Nasser turned down

the demand. Instead, he adopted a policy of divide and conquer by

accepting two members of the Brotherhood who were willing to serve as

independents, giving them minor posts. In

January 1953, Nasser overcame opposition from Naguib, banning all

political parties and creating a one-party system, the Liberation

Rally, which was meant to function as a national movement that would

replace all parties. The Communists and the Brotherhood condemned the

move, as both were excluded from participation in the new system.

Simultaneously, Nasser began using the more willing among the ulema ("religious scholars") of the al-Azhar University as

a counterweight to the Brotherhood. Meanwhile, debate rose within the

RCC as to the purpose of these measures. According to fellow officer Abdel Latif Boghdadi,

Nasser was the only RCC member who, even after ordering the dissolution

of political parties, favored to hold parliamentary elections. Outvoted, he still advocated holding elections by 1956. Nasser

was negotiating a British withdrawal from the Suez Canal and personally

led the Egyptian negotiation team in March 1953. Upon pressure from

him, Naguib proceeded with the abolition of the monarchy. He began

showing signs of independence from Nasser, however, by moderately

opposing land reform — even though the general population credited the

law to Naguib — and during a visit with the US Secretary of State, John

Foster Dulles, Naguib promoted himself as Egypt's head of state. Soon,

the two leaders began to openly compete for control of the country.

When Naguib moved to garner support from the Brotherhood and gain the

backing of old political institutions such as the former leaders of the

Wafd party, Nasser was determined to depose Naguib. In February 1954, army units loyal to Nasser kidnapped Naguib and announced that he had been relieved of all his posts. The RCC then "joyfully...proclaimed Nasser as Prime Minister". Soon after, large numbers of citizens joined protests demanding that Naguib be reinstated. As

a result of these demonstrations, a sizable group within the RCC, led

by Khaled Mohieddine, demanded that Naguib be released and allowed to

return to the Presidency and then hold free elections to select a new

president and prime minister. Nasser

was forced to agree and Naguib re-assumed the presidency. He still

appointed himself prime minister, however, and promoted Amer as

Commander of the Armed Forces — a position formerly occupied by Naguib.

Consequently, several high-ranking military officers resigned in

protest of what they deemed was the politicization of the army by

keeping it loyal to Nasser. Mohieddine was then informally exiled to

Europe to represent the RCC abroad and a campaign was launched by

Nasser's sympathizers in the press, including Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, publicizing Naguib's contact with the Wafd. In July, the feud between the two leaders was rekindled when Nasser and the British Foreign Affairs Minister, Anthony Nutting, signed an agreement, in principle, that would give way for the British withdrawal from the Suez Canal, as well as grant Sudan the

right to self-determination. Naguib was half-Sudanese and popular in

that country; he thought that most members of the RCC and most

Egyptians believed Sudan belonged to Egypt. Nasser was accused by many

in Egypt, including the Brotherhood, of distracting the issue of Sudan

with the withdrawal from Suez, but the Sudanese voted overwhelmingly in

favor of independence. The issue was settled in Nasser's favor when the

new Sudanese government opted for total "brotherly" relations with

Egypt. King Saud of Saudi Arabia attempted

to mend relations between Nasser and Naguib, but to no avail. In

general, Nasser's position was stronger due to the absence of

Mohieddine and the Sudanese officers, the growth of the Liberation

Rally, and because most of his original comrades in the RCC supported

him and also wanted Naguib to be removed. On 26 October, a Brotherhood member, Mohammed Abdel Latif, attempted to assassinate Nasser while he was delivering a speech in Alexandria,

celebrating the British withdrawal. The gunman, 25 feet

(7.6 m) away from him, fired eight shots, but all missed Nasser.

Panic broke out in the mass audience and Nasser raised his voice to

appeal for calm. He then stated "If Abdel Nasser dies... Each of you is

Gamal Abdel Nasser... Gamal Abdel Nasser is of you and from you and he

is willing to sacrifice his life for the nation." The crowd roared in

approval and the assassination attempt backfired, quickly playing into

Nasser's hands. Upon

returning to Cairo, he ordered one of the largest political crackdowns

in the history of Egypt, with the arrests of over 20,000 people, mostly

members of the Brotherhood, but also Communists, Wafd activists, and

sympathizers of these groups within the military leadership. Nasser

chose Gamal Salem,

a loyal officer, to head the military tribunal. Eight Brotherhood

leaders were sentenced to death, although the sentence of its chief

ideologue, Sayyed Qutb,

was commuted. Naguib was removed from the presidency and put under

house arrest, but was never tried or sentenced, and no one in the army

rose to defend him. The crackdown continued well into 1955. The

Brotherhood was dissolved and most of its leaders fled to other Arab

countries. Nasser's

street following was still too small to sustain his plans on reform and

secure him in office. To promote himself and the Liberation Rally, he

toured the country giving speeches and gained exclusive control of the state media organs. Both Umm Kulthum and Abdel Halim Hafez,

the leading Arab singers of the time, made songs praising his

nationalism and plays were produced denigrating his political

opponents. According to his associates, Nasser orchestrated the

campaign himself. Arab nationalist terms, such "Arab homeland" and

"Arab nation" infrequently began appearing in his speeches in 1954–55,

whereas prior he would refer to the Arab "peoples" or the "Arab

region." In January 1955, the RCC appointed him as president, pending

an election to the office. On 28 February 1955, Israel attacked the Egyptian-held Gaza Strip, declaring it necessary to suppress Palestinian fedayeen raids.

Nasser did not feel that Egypt was ready for a confrontation and did

not retaliate. This constituted a blow to his growing popularity, since it demonstrated the weakness of his armed forces. At the Bandung Conference in Indonesia in

April 1955, Nasser was treated as the leading representative of the

Arab countries and emerged as one of the key figures of the conference

and the Non-Aligned Movement. From then on, Nasser adopted the "positive neutralism" of Josip Broz Tito and Jawaharlal Nehru as his foreign policy regarding alliances with the Soviet Union and the West in relation to the Cold War. Nasser

felt if he was to maintain Egypt's position as leader of the Arab

world, he needed to acquire modern weapons to arm his forces. When it

became apparent that Western countries would not supply Egypt under financial and military terms acceptable to it, Nasser turned to the Soviet bloc and concluded a satisfactory armament agreement with Czechoslovakia in

September 1955. Through the "Czech arms deal", he enhanced his position

as an Arab leader defiant to the West. The Israelis also re-militarized

the Awja Demilitarized Zone on the Egyptian border in September. In January 1956, the new Constitution of Egypt was

drafted, entailing the establishment of a new single-party, the

National Union, which would select a nominee for the presidential

election whose name would be provided for popular approval. Nasser's

nomination for the post was put to the public in referendum in June; it

was approved by an overwhelming majority. Simultaneously with his

election, the RCC dissolved itself and its members resigned their military commissions. After

the three-year transition period ended with Nasser's official

assumption of power, his domestic and independent foreign policies

increasingly clashed with colonial interests of European powers in the

region, namely Britain and France. The latter condemned his strong support for the Algerian struggle for independence from France; the Eden government of Britain was agitated by Egyptian campaigns undermining the Baghdad Pact which Nasser viewed as disrupting "Arab solidarity." In addition, Nasser's adherence to neutralism and the Non-Aligned Movement, recognition of the Communist People's Republic of China, and the arms deal with the Soviet bloc, also alienated American support for his regime. Thus, the United States and Britain abruptly withdrew their offer to finance construction of the Aswan High Dam. On

26 July 1956, in retaliation for the loss of funding and to help pay

for the Aswan project, Nasser gave a speech in Alexandria where he

denounced Western influence in the Arab world and announced the

nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, and how existing stockholders would be paid off. The

nationalization move was greeted by the crowd very emotionally, and

throughout the Arab world, thousands ran into the streets shouting

slogans of support. US ambassador Henry A. Byroade stated

"I cannot over-emphasize [the] popularity of the Canal Company

nationalization within Egypt, even among Nasser's enemies." According

to Aburish, this was Nasser's largest pan-Arab triumph yet and "soon

his pictures were to be found in the tents of Yemen, the souks of Marrakesh, and the posh villas of Syria." The official reason given for the nationalization was that funds from the Suez Canal would be used for the construction of the dam in Aswan. Nasser

realized that this move would provoke a strong reaction from Britain

and France, both of which had major shareholdings in the Suez Canal. He

believed, however, that Britain would not be able to intervene

militarily for at least two months after the announcement, and

dismissed Israeli action as "impossible." In early October, the United Nations Security Council met

on the matter of the canal's nationalization and adopted a resolution

recognizing Egypt's right to control the canal as long as it continued

to allow passage through it for foreign ships. After this agreement, "Nasser estimated that the danger of invasion had dropped to 10 percent." Shortly thereafter, however, Britain, France, and Israel colluded in a secret agreement to take over the Suez Canal and occupy parts of Egypt. On 29 October 1956, Israel crossed the Sinai,

overwhelmed Egyptian army posts, and quickly advanced through the

peninsula to their objectives. Two days later, British and French

planes bombarded Egyptian airfields in the canal zone. Amer panicked

and withdrew Egyptian forces from the Sinai and suggested that Nasser

make a ceasefire. According to Boghdadi, Nasser described the Egyptian army as "shattered" and appeared a "broken man." Nonetheless, his prestige at home and among Arabs was undamaged. Nasser

personally took over command of the military and, aware that he was

unable to stop the invasion, he coordinated with King Saud to land Egyptian Air Force planes in Saudi Arabia and Sudan to avoid destruction. He then telephoned King Hussein of Jordan and Shukri al-Kuwatli of

Syria, asking them to stay out of the fighting. When Hussein objected

and offered to participate in Egypt's defense, Nasser warned him "to

save his army from destruction." He followed by issuing orders to block

the canal by sinking about fifty ships at its entrance. In Port Said, he berated Amer and Salah Salem, who continually insisted on surrendering, in front of other officers and vowed that "Nobody is going to surrender." Meanwhile, the American Eisenhower administration was outraged at the tripartite aggression, their attempts to cover it in diplomacy and its timing during the crisis in Hungary. Dwight Eisenhower publicly condemned it and supported United Nations resolutions demanding withdrawal, Israel's return to the 1949 armistice lines and for a United Nations Emergency Force to

be stationed in the Sinai. By the end of December, the British and

French forces had totally withdrawn from Egyptian territory, and on 8 April 1957, the canal was reopened. It was not until a month later that Israel completely withdrew from the Sinai. With

this, Nasser's position was enormously enhanced by the widely perceived

failure of the invasion and British attempt to topple him. Nutting

claimed the crisis "established Nasser finally and completely" as the rayyes ("chief") of Egypt. In January 1957, the US adopted the Eisenhower Doctrine, pledging to protect Middle Eastern countries

from Communism and its "agents." Although Nasser was not a supporter of

Communism, his promotion of Arab nationalism threatened surrounding

pro-Western states. Eisenhower attempted to isolate and reduce him by

considering support of his ally King Saud as a counterweight. Previously, in October 1956, a pan-Arabist coalition won parliamentary elections in Jordan, making Sulayman al-Nabulsi, a staunch supporter of Nasser, the country's prime minister. Relations

between Nasser and King Hussein soured when al-Nabulsi and all other

pro-Nasser elements in the cabinet and army were subsequently arrested

and dismissed; Hussein alleged that Nasser and his Jordanian allies

were attempting to overthrow him. Nasser berated Hussein on his

Cairo-based Voice of the Arabs radio station, accusing him of being "a tool of the imperialists." Meanwhile,

King Saud was gradually resenting Nasser's popularity among the Saudi

people and his references to Saudi oil as belonging to all the Arabs;

when Hussein requested military assistance from Saud, he complied,

sending 4,000 troops to Jordan as a protective measure. Despite opposition from the governments of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Lebanon, Nasser gained influence among many of the citizens of those and other Arab countries. Palestinians in

Jordan saw him as the only Arab leader that could challenge Israel and

many of the country's indigenous citizens supported him as well.

Together, they formed Arab unity clubs, youth organizations, and secret

civilian formations. His followers in Lebanon and the Egyptian embassy

in Beirut — the

press center of the Arab world — bought outlets of the Lebanese media to

sponsor him. Many Lebanese politicians were salaried by Egypt to take

pro-Nasser stands, but others like Kamal Jumblatt and Saeb Salam,

genuinely supported him. Nasser also enjoyed the full support of Arab

nationalist organizations throughout the region, including the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), Najd al-Fatat (in Saudi Arabia), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Arabia, and to a certain degree the Ba'ath party

which operated in a number of countries. His followers were numerous

and well-funded, but lacked any permanent structure and organization.

They called themselves "Nasserists," despite Nasser's objection to the label (he preferred the term "Arab nationalist.") By the end of 1957, Nasser nationalized all remaining British and French assets in Egypt, including the tobacco, cement, pharmaceutical, and phosphate industries.

Because the previous opening to outside investment and the offering of

tax incentives had yielded no results, he nationalized more companies

and made them a part of his economic development organization. He

stopped short of total government control: two-thirds of the economy

was still in private hands. Yet, this effort did achieve a measure of

success, with agricultural production increasing and investment in

industrialization rising. Nasser initiated the Helwan steelworks,

which were on their way to becoming Egypt's largest enterprise,

providing the country with product and the employment of tens of

thousands of people. Nasser also decided to cooperate with the USSR in

the construction of the Aswan High Dam since the US withdrew its offer

following the nationalization of the Suez Canal. Nasser eventually

abolished the Liberation Rally, with the National Union taking its

place. The National Assembly was to be the national representative

body, allowing Nasser to sideline former Liberation Rally leaders Gamal

Salem and Anwar Sadat.

In addition, occasional arbitrary crackdowns against the Brotherhood

and the Communists occurred during this period, particularly in April

1957. Despite his popularity, Nasser's credentials as Arab leader were at stake after the events in Jordan. Later in 1957, Turkish troops massed along the border with Syria, accusing it of harboring Turkish

Communists. In response, Saud announced his support for Arab Syria

against Turkey. To outdo him, in August, Nasser decided to land 4,000

Egyptian troops in the Syrian port city of Latakia, reclaiming his prestige, especially with the Syrian people. Beginning in 1957, Syria appeared close to becoming a Communist satellite; it had a highly organized Communist Party and the army's

chief of staff, Afif Bizri, was a Communist sympathizer. Nasser told an

initial Syrian delegation that they needed to rid their government of

Communists, but the delegation countered and warned him that only total

union with Egypt would defuse the "Communist threat." Although Nasser

initially turned them down, suggesting that it would take a minimum of

five years to establish a feasible political union, he

became more afraid of a Communist takeover when the second Syrian

delegation composed of military officers was led by Bizri on 11 January

1958; Bizri personally discouraged Syro-Egyptian unity. Afterward, Nasser opted for a total merger and the resulting United Arab Republic (UAR)

came into being on 1 February 1958. Nasser became the republic's

president and very soon carried out a crackdown against the Syrian

Communists and opponents of the union, which included dismissing Bizri

and former prime minister Khaled al-Azem from their posts. On 24 February, Nasser traveled to Damascus in a surprise visit to celebrate the union. He was welcomed by crowds of tens of thousands. Ahmad bin Yahya, King of North Yemen, dispatched Crown Prince Imam Badr to

Damascus with proposals to include their country in the new republic.

Nasser and Quwatli agreed to establish a loose federal union with

Yemen, rather than a total integration, creating the United Arab States.

While Nasser was in Syria, King Saud was allegedly planning on having

him assassinated during his flight back to Cairo. He offered to pay the

head of the Syrian security services, Abdel Hamid Sarraj,

to order Syrian jet fighters to shoot down Nasser's plane. Sarraj,

however, was a staunch supporter of Nasser and pretended to agree with

Saud's plan only to reveal the plot to Nasser. On 4 March, Nasser stood

on the balcony of the Diafa Palace of Damascus and waved a copy of the

Saudi check in the air for the masses to witness. As a consequence of

Saud's scheme, he was forced by senior members of the Saudi royal family to informally cede most of his powers to his brother, King Faisal, an advocate of pan-Islamic unity rather than Arab nationalism and a major opponent of Nasser. A

day after announcing the attempt on his life, Nasser established a new

provisional constitution proclaiming a 600-member National Assembly

(400 from Egypt and 200 from Syria) and the disbanding of all political

parties, including the Ba'ath. Nasser gave each of the provinces two

vice-presidents; Boghdadi and Amer were assigned to Egypt and Sabri al-Assali and Akram al-Hawrani to Syria. Nasser then left for Moscow to meet with Nikita Khrushchev.

At the meeting, Khrushchev pressed Nasser to lift the ban on the

Communist Party, but Nasser refused, stating it was an internal matter

which was not a subject of discussion with outside powers. Khrushchev

was reportedly taken aback and denied he had meant to interfere in the

UAR's affairs and the issue was settled since both leaders did not want

a rift between their two countries.

In neighboring Lebanon, president Camille Chamoun,

an opponent of Nasser, viewed the creation of the UAR with worry.

Pro-Nasser factions in the country began clashing with supporters of

Chamoun, culminating in a civil strife by

May 1958. The former favored merging with the UAR, while the latter

feared the new country was a Communist satellite and threatened

Lebanon's independence. Although Nasser claimed no intention to covet

Lebanon, seeing it as a "special case," he

felt obligated to back his supporters in the country through sending

money, light arms, and training officers to prevent Chamoun from

gaining a second term as president. Almost simultaneously, on 14 July, Iraqi army officers Abdel Karim Qasim and Abdel Salam Aref staged a military coup against King Faisal of Iraq, who was immediately killed. Two days later Nasser's most serious enemy in the Middle East, Nuri as-Said, the prime minister of Iraq, was also killed. Nasser, who was in Belgrade, Yugoslavia,

while the coup was undertaken, extended recognition of the new

government and stated that "any attack on Iraq was tantamount to an

attack on the UAR." The

next day US marines and British special forces landed in Lebanon and

Jordan, respectively, to protect the two countries from falling to

pro-Nasser forces as well. To Nasser, the revolution in Iraq left the road for Arab nationalism unblocked. Although most members of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council (RCC)

were Nasserists and favored joining Iraq with the UAR, Qasim had

animosity towards him. Aburish states that reasons for this could have

included Nasser's refusal to cooperate with and encourage the Iraqi

Free Officers a year before the coup or Qasim's view that Nasser

threatened his supremacy as leader of Iraq.

Later in July, Fuad Chehab was

to be elected Lebanon's new president and he met Nasser at the

Lebanese-Syrian border. He explained to Chehab that he would not pursue

unity with Lebanon, but he did not want the country to be used as a

base against him. Resulting from this meeting was an agreement ending

the crisis in Lebanon, with Nasser ceasing to supply his partisans and

the US setting a deadline for withdrawing from the area. In

Damascus, on 19 July, Nasser gave one of his most important speeches

addressing the new regional realities. According to researcher May

Oueida's thesis on the speech, he adopted a theme of successfully bridging the different sounds of Egyptian, Syrian, and Iraqi Arabic, and rose to a classical Arabic without

losing or boring his audience. For the first time Nasser was opting for

full Arab union. He had no plan, however, on how to incorporate Iraq

into the UAR. In the fall of 1958, Nasser formed a tripartite committee, consisting of Mohieddine, al-Hawrani, and Salah al-Din Bitar to

oversee developments in Syria. By moving the latter two, who were

Ba'athists, to Cairo, he neutralized important political figures who

had their own ideas about how Syria should be run within the UAR. He

put Syria under Sarraj, who effectively reduced the province into a police state by imprisoning and exiling Communists — including party leader Khalid Bakdash — and

landholders who objected to the introduction of Egyptian agricultural

reform in Syria. In December 1959, aware that things were not working

in Syria, Nasser appointed Amer as governor-general alongside Sarraj.

Syria's leaders reacted with opposition to the appointment and many

resigned from their government posts. Nasser later met with the

opposition leaders, which included al-Hawrani, Bitar, and Ba'ath founder Michel Aflaq,

and in a heated conversation, exclaimed that he was the "elected"

president of the UAR and those who did not accept his authority could

"walk away." Meanwhile,

Nasser began smuggling agents from Syria into Iraq and senior Iraqi

army officers began asking for support in launching a coup against

Qasim. On 8 March 1959, an anti-Qasim rebellion broke out in the

northern Iraqi city of Mosul led

by Abdel Rahman al-Shawaf, a member of the Iraqi RCC who was previously

in touch with UAR authorities. Turmoil soon spread throughout Iraq,

with the country's ethnic and religious groups attacking each other

while pro-Qasim forces gained the upper hand against al-Shawaf. Nasser

considered dispatching UAR troops into Iraq to aid his sympathizers,

but soon decided against it. His

advisers, namely Sarraj and Amer, insisted that the pro-Nasser forces

were winning and Qasim was about to be toppled. Within four days,

however, Qasim's forces captured Mosul and al-Shawaf was killed.

Already strained relations between Nasser and Qasim grew increasingly

bitter, with the former considering the latter as unworthy and

dependent on the USSR while Qasim looked down on Nasser's Arab

nationalism, believing only an alliance with the USSR would help the

Arabs succeed against Israel. Nasser blamed the Arab nationalist defeat

on the Communists and upon returning to Cairo, he dismissed and

arrested many Communists who held influential positions in the press

and government, including his old comrade Khaled Mohieddine, who had

been allowed reentry into Egypt in 1956. In Syria, opposition to union with Egypt mounted; Syrian army officers resented being subordinated to Egyptian officers, Syrian Bedouin tribes

received money from Saudi Arabia to prevent them from becoming loyal to

Nasser, Egyptian-style land reform was resented for damaging Syrian

agricultural production, the Communists began to gain influence among

lower-income workers, and the intellectuals of the Ba'ath who had

supported union rejected the single-party system. Nasser was not fully

capable to address problems in Syria because they were foreign to him

and instead of appointing Syrians to run Syria, he handed this task to

Amer. In

Egypt, the situation was more positive, with a GNP growth of 4.5

percent and a rapid growth of industry. In 1960, he nationalized the

Egyptian press, effectively reducing it to his personal mouthpiece. On

28 September 1961, Syrian army units in Damascus rose against the UAR

and declared Syria's independence. Amer and Sarraj were exiled, and

army units in northern Syria loyal to the union failed to prevent the

country's secession. Nasser sent Egyptian Special Forces to Latakia to

oppose Syria's withdrawal, but ordered them withdrawn after two days,

claiming he refused to allow inter-Arab fighting. In a speech to the

Arab world, he admitted making mistakes with Syria, refused to condemn

the secessionists, and accepted personal responsibility for the UAR's

breakup. Privately, however, he accused Qasim, the Saudis, the

Jordanians, and other Arab governments of contributing to the fall of

the UAR. According to Heikal, Nasser suffered something resembling nervous breakdowns as well as deteriorating health and an increase in smoking after the dissolution of the union. Fearing similar action in Egypt, he sought to pursue an increasingly socialist agenda in the country. In

October 1961, Nasser embarked on a major nationalization program,

believing the total adoption of socialism was the answer to his

problems and would have protected him from what happened in Syria. The

Charter for National Action was undertaken, creating youth groups,

socialist study institutes, laws regarding the acquisition of wealth,

and agricultural cooperatives. In the process, the National Union was

renamed the Arab Socialist Union. By 1962, as a result of these measures, government ownership of Egyptian business reached 51 percent. The measures also caused more domestic oppression, with thousands of Islamists being imprisoned, including dozens of military officers. Nasser's tilt toward a Soviet-style system led his aides Abdel Latif Boghdadi and Hussein el-Shafei to submit their resignations. At an Arab League summit

in August 1962, Nasser pulled out his delegation after arguments with

Syria, which wanted the dismissal of the organization's

secretary-general, Abdel Khalek Hassouna, complaining that he only followed Nasser's orders. Nasser's fortunes on the Arab stage unexpectedly changed when Yemeni officers led by Abdullah as-Sallal, a supporter of Nasser, rebelled against Imam al-Badr of the Kingdom of North Yemen, on 27 September 1962. The officers proclaimed their country the Yemen Arab Republic and

Nasser immediately recognized its legitimacy. Meanwhile, al-Badr and

his partisans were receiving increasing support from Faisal of Saudi

Arabia to reinstate the kingdom, leading Nasser to dispatch Egyptian

troops to strengthen the new government on 6 October. They were unable

to defeat the royalist forces, who by then controlled a third of the

country and as the war continued, many Yemenis came to resent the

Egyptian presence, despite Nasser's attempts to foster economic growth

and offer military support. His influence on the ruling politicians

made Nasser many enemies. Most

of Nasser's old colleagues questioned the wisdom of continuing the war,

but Amer assured numerous times that victory was near. By 1963, Nasser had sent 15,000 Egyptian soldiers to Yemen, but the war remained a stalemate. The Yemen War caused heavy implications for the Saudi royal family when a pro-Nasser clique was formed, culminating in the declaration of the Free Princes by Talal ibn Abd al-Aziz.

After Nasser allowed the Free Princes movement to operate from Cairo,

it gained a considerable following among minor Saudi princes and the

co-founder of Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, Abdullah al-Tariki. In addition to those developments, Algeria became

independent of France. Nasser considered this a victory for himself and

the Arab nationalist movement. Then, on 8 February 1963, a military

coup led by Ba'athists and Nasserists was staged in Iraq, overthrowing

Qasim who was shot dead. Although Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr orchestrated the coup, Nasser's sympathizer Abdel Salam Aref was chosen to be the new president. The

Iraqi and Syrian regimes, both ruled by the Ba'ath party, soon sent

Nasser delegations to push for a new Arab union on 14 March 1963.

Nasser berated the attendees for being "phony nationalists" and

constantly changing direction. He

presented them a detailed plan for unity, favoring a federal system

which began with the merger of defense and foreign policy. A four-year

term for president was stipulated, in addition to legislative councils

being responsible for overseeing the functions of the state. The

measures would be implemented slowly and in segments. By the end of his

lecture, Nasser stated that he was the "leader of the Arabs and without

me you are nothing. Either take what I have to offer you or leave and

never return." During

the early 1960s in Egypt, Nasser became highly concerned with Amer's

inability to train and modernize the army, as well as the "state within

a state" he created by transforming the army and the security apparatus, which is under the direction of Salah Nasr, into "a separate fiefdom loyal to him personally," according to Aburish. None

of Nasser's old colleagues had informed him of the corruption and

lawlessness undertaken by Amer and the army officers loyal to him since

they thought the relationship between Nasser and Amer, his

second-in-command, was solid. Therefore, any claims of power abuse

would be dismissed. After realizing the extent of Amer's control in the

country, however, Nasser appointed himself chief of the armed forces,

replacing Amer, in 1963. Although Amer was officially demoted, he

remained in a strong position and many leading officers continued to

express loyalty to him. According to Boghdadi, the stress caused by the collapse of the UAR and Amer's increasing autonomy led Nasser, who had diabetes, to practically live on painkillers from then on. In

order to organize and solidify his popular base with Egypt's citizens

to counter the influence of the army, Nasser introduced a new

constitution and the National Charter in 1964. The latter called for

universal health care, provision of housing, building of vocational

schools, widening the Suez Canal, an increase in women's rights, and

developing a program for family planning. In addition, he attempted to

maintain oversight of the country's civil service to prevent it from

inflating and consequently becoming a burden to the state. Prior

to undertaking these new measures, beginning in 1961, Nasser sought to

firmly establish Egypt as the leader of the Arab world and to promote a

second revolution in Egypt with the purpose of merging Islamic and

socialist thinking to satisfy the will of the general populace. To

achieve this, he began executing several reforms to modernize the al-Azhar Mosque, which is the de facto leading authority in Sunni Islam, and ensure its prominence over the Muslim Brotherhood and the more conservative Wahabbism promoted by Saudi Arabia. Nasser used his influence with al-Azhar to create

changes in the syllabus, which trickled to the lower levels of Egyptian

education. He allowed gender-mixed schools, introduced evolution as

an acceptable subject matter to discuss, amended divorce laws, and

merged religious courts into civil ones. He also forced al-Azhar to

issue a fatwa readmitting Shia Muslims, Alawites, and Druze into mainstream Islam; for centuries before, al-Azhar deemed them as "heretics" and non-Muslims. In January 1964, Nasser called for an Arab League summit in Cairo, with the stated purpose of establishing a unified Arab response against Israel's plans to divert water from the Jordan River to irrigate the Negev.

Although he discouraged Syria and Palestinian paramilitary factions

from provoking the Israelis, admitting that he had no plans for war

with Israel, Nasser nonetheless called for the creation of the United Arab Command (UAC).

Nasser blamed the lack of unity among the Arab states for what he

deemed as "the disastrous situation" regarding the water diversion

scheme. In

a move to cede or share his responsibility and leadership position with

the Palestine issue, Nasser decided to establish an entity to represent

the Palestinians. In May, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), an umbrella group that included various Palestinian factions, was founded and its head was to be Ahmad Shukeiri, Nasser's nominee. Nasser aligned himself with the ANM of George Habash and used the PLO to counter the support Fatah (not a PLO member) was receiving among Palestinians. Although

Nasser had secret contacts with Israel in 1954–55, he eventually

believed peace with Israel would be impossible, considering it an

"expansionist state that viewed the Arabs with disdain." Later in 1964, Nasser was made president of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and held the second conference of the organization in Cairo that same year. During

the presidential elections in Egypt, Nasser was reelected to another

six-year term, taking his oath on 25 March 1965. He was the only

candidate for the position, with virtually all of his political

opponents being forbidden by law from running for office and his

supporters being reduced to mere followers. That same year, he

imprisoned Sayyed Qutb,

the Muslim Brotherhood's chief ideologue. Qutb wrote a book from his

jail cell condemning Nasser as the representative of a "new age of

ignorance". Unable

to silence Qutb by incarceration, Nasser accused him of conspiring in a

Saudi attempt to assassinate him and had Qutb executed in 1966; the

Muslim Brotherhood consequently sentenced Nasser to death. Sometime during 1966, he suffered, but survived, a massive heart attack. In early 1967, Soviet premier Alexey Kosygin sent

Nasser a warning through Sadat, who was visiting Moscow, that Israel

was about to carry out a large-scale assault against Syria. More

warnings followed in the next few months, and King Hussein, aware of

the intelligence situation, cautioned Nasser in April not to be dragged

into a war. That same month, pressure on him to act by Syria, Saudi

Arabia, and the PLO, as well as the general Arab populace, mounted

after an aerial battle between Syria and Israel resulted in the downing

of six Syrian planes. Convinced that Israel was determined to attack

Syria, he asked UN Secretary-General U Thant to withdraw UNEF forces from Sinai. On 23 May, Egyptian troops moved into Sharm el-Sheikh and Nasser ordered the Straits of Tiran closed to Israeli shipping. After the blockade, he gave a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on 29 May saying, "the issue was not UNEF or closing the Strait of Tiran; the issue is the rights of the Palestinian people." This

was the same message delivered a week earlier during a visit to an air

base in the Sinai. The speeches signaled that Nasser believed war was

inevitable. King Hussein arrived in Cairo on 30 May and committed Jordan to the United Arab Command — an alliance which also included Egypt and Syria — under the command of Egyptian general Muhammad Sidqi.

Amer anticipated an Israeli attack and advocated Egypt launch a

preemptive strike. He was backed by former Syrian prime minister Amin al-Hafiz.

Due to assurances, however, from the American administration and the

USSR that Israel would not attack, Nasser refused Amer's suggestion,

insisting that Egyptian forces in the Sinai should only act

defensively. In addition, he questioned the Egyptian military's

readiness since the air force lacked pilots, the army reserve lacked

training, and Nasser doubted the competence of Amer's hand-picked

officers. Simultaneously, Egypt was facing a financial crisis leading

him to believe that the country could not afford a war that would last

even a few days. Nonetheless, Nasser eventually began changing

positions from acting to avoid war to giving speeches claiming war was

inevitable. On the morning of 5 June, the Israeli Air Force (IAF)

struck Egyptian air fields, destroying much of the Egyptian Air Force.

Before the day ended, Israeli armor had cut through Egyptian defense

lines, capturing the town of el-Arish. According to Sadat, it was only when they captured el-Qantarah el-Sharqiyya, cutting off the Egyptian garrison at Sharm el-Sheikh, that Nasser became aware of the gravity of the situation. After

hearing of the attack, he rushed to the army headquarters to inquire

about the military situation. It was here that the simmering conflict

between Nasser and Amer came into the open when, according to present

officers, they burst into "a non-stop shouting match." Nasser

accused Amer of giving unsatisfactory answers to his questions, while

Amer asked Nasser for more time to launch a counterattack against the

Israelis. The

Supreme Executive Committee, set up by Nasser to oversee the conduct of

the war, attributed the repeated Egyptian defeats to the Nasser-Amer

rivalry and to Amer's overall incompetence. Despite

the extent of Israel's quick military gains, for the first four days

the general population in the Arab states believed the fabrications of

Arab radio stations which claimed victory near. On 8 June, Nasser

appeared on television to inform Egypt's citizens of their country's

defeat. Israel had occupied the entire Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip of Egypt, the West Bank of Jordan, and the Golan Heights of Syria by 10 June. The same day, Nasser announced his resignation on television, ceding all presidential powers to his then-vice president Zakaria Mohieddin. Mohieddin had not been informed of this decision and resigned from his cabinet post in protest, rarely seeing Nasser again. No

sooner was the statement broadcast, however, were tens of thousands of

Arabs pouring into the streets in mass demonstrations throughout Egypt

and across the Arab world rejecting his resignation. Many cried in open

sympathy with Nasser's position. Demonstrators adopted the Cairo slogan

"We are your soldiers, Gamal!" Upon these reactions, Nasser retracted

his decision the next day. His popular support also allowed him to

arrest a large number of army officers, but not Amer who was given a

hero's welcome in his home village. At the August 1967 Arab league summit in Khartoum, Sudan,

Nasser's usual commanding position was reduced as the attending heads

of state expected King Faisal to lead. The two leaders agreed to

establish a ceasefire in the Yemen War. Also established was the

offering of financial subsidies to Egypt, Jordan, and Syria by Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait. The conclusion of the summit resulted in what became known as the "three nos":

no peace, no negotiation, and no recognition of Israel. Although they

were still privately working against each other, Nasser and Faisal

publicly rode through the streets of Khartoum in an open-top car with

their hands clasped in a show of unity to please the crowds. The

USSR soon resupplied the Egyptians with about half of their former

arsenals and broke diplomatic relations with Israel. Following the war,

Nasser had cut relations with the US and according to Aburish, Nasser's

policy of "playing the superpowers against each other came to an end." Upon

returning to Cairo, Nasser soon had Amer, Sidqi, and nine other

generals arbitrarily arrested due to both popular and governmental

accusations that they were attempting to organize a military coup

against him. Amer was arrested as he was leaving Nasser's home where he

was invited for a "meeting." On 14 September, he committed suicide

while in detention. According to Boghdadi, allegations from Amer's

family that the government allowed him to commit suicide, were true.

Despite having a part in arranging Amer's suicide — which he felt was

necessary — Nasser spoke of losing "the person closest to me," and did

not fully recover from the psychological blow. In

this brief period, Nasser moved toward creating a full dictatorship in

Egypt by appointing himself the additional roles of prime minister and

commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In November 1967, Nasser accepted UN Resolution 242 which

ambiguously called for Israel's withdrawal from territories acquired in

war. His supporters claimed the move was meant to gain time to prepare

for another confrontation with Israel. Contrarily, his detractors in

Egypt and the Arab world believed Nasser's acceptance of the resolution

was a sign that he wanted to negotiate the Palestinian issue, removing

it from the top of his agenda. While

his traditional Arab enemies (Saudi Arabia and Jordan) still conspired

to reduce his prominence or remove him all together, Nasser maintained

good relations with them following the Khartoum summit, partly because

of financial dependence on the Persian Gulf States.

On the other hand, his traditional allies (Syria, Iraq, Algeria, and

the PLO) opposed his recent moves and formed a "rejectionist front."

In January 1968, Nasser commenced the War of Attrition against Israel, ordering his forces to begin harassing the Israelis east of the now-blockaded Suez Canal. In the same month, he allowed the Soviets to construct naval facilities in Port Said, Marsa Matruh, and Alexandria. Then in March, Fatah, a Palestinian paramilitary group, under the leadership of Yasser Arafat faced off with Israel in Jordan, in what became known as the Battle of Karameh.

Although they suffered over 100 casualties, while Israel lost 28

soldiers, the battle was perceived as an Arab-Palestinian victory as

Israel withdrew without achieving its goal — destruction of the

Palestinian fedayeen base. Nasser immediately dispatched Heikal to

invite Arafat to Cairo. Nasser met with him and his colleagues, Farouk Qaddoumi and Salah Khalaf,

soon after. He offered the Fatah movement arms and financial support,

but advised Arafat to think of peace with Israel and establishing a Palestinian state comprising the West Bank and the Gaza Strip; Nasser decided to cede his leadership of the conflict with Israel to Arafat. In July, the two leaders left for Moscow where Nasser introduced Arafat to high-level Soviet officials. As

the war against Israeli positions in the Sinai was underway, Israel

retaliated by heavily bombing key Egyptian military and civilian

infrastructure and causing a large exodus of Egyptians from the western

bank of the Suez Canal, leading to a large refugee population. As a

result, Nasser ordered all military activities to cease, while

embarking on a program to build a network of internal defenses. The war

resumed in March 1969 and Nasser received the financial backing of the

Gulf Arab states while the PLO spearheaded infiltrations into Israel

from Lebanon and Jordan. In November, he brokered an agreement between the PLO and the Lebanese military granting

the Palestinians the right to use Lebanese territory to attack Israel.

A month later, in December 1969, Nasser appointed Sadat and Hussein el-Shafei,

a former RCC comrade, as his vice presidents. By then, relations with

his other RCC comrades, namely Khaled and Zakaria Mohieddin and former

vice president Ali Sabri became strained. Nasser, with support from King Hussein, accepted the Rogers Plan in

June 1970, but it was immediately rejected by Israel and the PLO, as

well as most of the Arab states and Sadat. Nasser was openly

considering replacing Sadat with Boghdadi; he had since reconciled with

the latter. Nasser's confidants — Heikal and Abdel Magid Farid, among

others — however, insisted Nasser's acceptance of the US peace plan was a

strategic one aimed at exposing Israel's reluctance to negotiate with

the Arabs. Meanwhile, in July, King Hussein informed Nasser of his dissatisfaction with the PLO's behavior in Jordan. On 6 September, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine hijacked and blew up four

emptied international airplanes on Jordanian soil, despite protests

from Nasser who issued condemnations against the hijackers. Ten

days later, King Hussein sent in his army to rout out Palestinian

guerrilla forces from the country in what became known as "Black September." Escalations in violence brought the Middle East close to a wider war, prompting Nasser to hold an emergency Arab League summit on

27 September. The attending heads of state launched verbal

denunciations against each other, while Nasser pleaded with Arafat and

Hussein "to stop it." At the end of the conference, he forged an agreement ending the hostilities. On 28 September 1970, at the conclusion of the summit and hours after escorting Emir Sabah III of Kuwait,

the last Arab leader to depart, Nasser suffered a heart attack. He was

immediately transported to his house and was pronounced dead soon

after. His wife Tahia, Heikal and Sadat were present — the latter read the Qur'an at his deathbed. Following the announcement of Nasser's death, Egypt and the Arab world were in a state of shock. Because

of his ability to motivate nationalistic passions, "men, women and

children wept and wailed in the streets" after hearing of his death. As

a testament to his unchallenged leadership of the Arab people,

following his death, a Beirut-based newspaper stated, "One hundred

million human beings — the Arabs — are orphans." Sherrif

Hatatta, an Egyptian political activist who was imprisoned by Nasser

for four years claimed that "Nasser's greatest achievement was his

funeral. The world will never again see five million people crying

together." His funeral procession through Cairo, on 1 October, was attended by at least five million mourners. The

10-kilometre (6.2 mi) procession to his burial site began at the

RCC headquarters with MiG-21 jet fighters flying overhead. His

flag-draped coffin was attached to a gun carriage pulled by six horses

and led by a column of cavalrymen. All Arab heads of state attended. King Hussein of Jordan and the PLO leader Yasser Arafat cried openly while Muammar al-Gaddafi of Libya reportedly fainted twice. Although no major Western dignitaries were present, Soviet premier Alexey Kosygin showed up. Almost

immediately after the procession began, mourners had engulfed Nasser's

coffin shouting "There is no God but Allah, and Nasser is God's

beloved... Each of us is Nasser." Police unsuccessfully attempted to

quell the crowds and as a result, most of the foreign dignitaries

surrounding his coffin — including Kosygin, Hussein, French premier Jacques Chaban-Delmas, and Haile Selassie of Ethiopia — were evacuated. The final destination was the Nasr Mosque, renamed Abdel Nasser Mosque, where Nasser was buried. The

general Arab reaction was one of mourning, with thousands of people

pouring onto the streets of major cities throughout the Arab world.

Over a dozen people were killed in Beirut as a result of the chaos and

in Jerusalem, roughly 75,000 Arabs marched through the Old City chanting "Nasser will never die." The Muslim Brotherhood, however, issued a statement to its followers to "not pray for the faithless Nasser." Nasser's

legacy is much debated today. To his sympathizers, he was a leader who

reformed his country and re-established Arab pride both inside and

outside of it. They testify that under him, Egyptians enjoyed

unprecedented access to housing, education, health services, and

nourishment as well as other forms of social welfare. Nasser is

credited for severely curtailing British influence in Egypt, elevating

it to upper world circles, and reforming the country's economy through agrarian reform,

major modernization projects such as Helwan and the Aswan High Dam, and

various nationalization schemes. While Nasser was president, Egypt

experienced a cultural boom, particularly in theater, film, literature,

and music. Nasser's Egypt dominated the Arab world in these fields, producing singers such as Umm Kulthum and Mohammed Abdel Wahab, literary figures such as Naguib Mahfouz and Tawfiq el-Hakim, and producing over 100 films a year compared to just more than a dozen in recent years. Time magazine

stated that despite his mistakes and shortcoming, Nasser "imparted a

sense of personal worth and national pride that they [Egypt and the

Arabs] had not known for 400 years. This alone may have been enough to

balance his flaws and failures." Until the present day, he serves as an iconic figure throughout the Arab world. Through

his speeches and his actions, and because he was able to symbolize the

popular Arab will, Nasser inspired several nationalist revolutions in

the Arab world. Muammar al-Gaddafi who overthrew the monarchy of Idris I in Libya in 1969, considered Nasser his hero and after his death, sought to succeed him as the "leader of the Arabs." Ahmed Ben Bella who led Algeria to gain independence from France in 1962 was a staunch Nasserist and held him in great esteem. Abdullah as-Sallal drove out the king of North Yemen in the name of Nasser's pan-Arabism. Other Arab nationalist-led coups influenced by Nasser included those that occurred in Iraq and Syria in 1963. They were led by Abdel Salam Aref and Luai al-Atassi, respectively. Both were strong supporters of the Egyptian president and advocated pan-Arab unity. George Habash, founder and secretary-general of the Arab Nationalist Movement, embraced Nasser's ideas and helped spread them throughout the Arab world, particularly among the Palestinians. He was a recipient of the Hero of the Soviet Union title. Opponents

of Nasser in Egypt accuse him of committing numerous human rights

violations, thwarting democratic progress, and leading a repressive

administration that imprisoned thousands of Egyptians who opposed him,

including Communists and members of the Muslim Brotherhood. Western

political scientists claim his largely charismatic and direct

relationship with the Egyptian people "rendered intermediary

organizations and individuals unnecessary." Therefore,

because of Nasser's failure to create institutions, Egypt returned to

the unstable political state it was in before his coming to power.

Author Mark Cooper states Nasser's legacy was a "guarantee of

instability." Nasser's

failure to democratize Egypt was a major rallying point for his

opponents, although his supporters argue that he attempted to lay the

groundwork for democracy through various liberalization reforms.

Ultimately, Nasser's efforts failed in this respect and democracy

remains virtually absent in Egypt until the present day.

Vice

President Anwar Sadat, who had been interim president following

Nasser's death, was officially selected to succeed him on 5 October.

Unlike Nasser, Sadat was not a passionate advocate of pan-Arab unity

and concentrated on restoring Egyptian dignity and territory lost in

the 1967 War. Aware

of the Egyptian people's attachment to Nasser's memory, Sadat declared

in his inauguration speech before the National Assembly on 7 October

1970, "I have come to you along the path of Gamal Abdel Nasser and I

believe that your nomination of me to assume the responsibility of the

presidency is a nomination for me to continue the path of Nasser." Following the 1973 War,

however, in which Egypt's army performed better than in previous wars,

but ultimately failed to recapture the Sinai Peninsula, Sadat launched

a campaign to eradicate Nasser's influence and Nasserism as a whole in

Egypt. This

angered a large section of Egyptian society who saw the attempt as an

assault on their national memory and political views. According to

Egyptian journalists Hani Shukrallah and Hosny Guindy, because of the

campaign, until modern times, "Half the country [Egypt]... is at war

with Abdel-Nasser, half with Anwar El-Sadat."