<Back to Index>

- Scientist and U.S. Founding Father Benjamin Franklin, 1706

- Painter Pieter van Bloemen, 1657

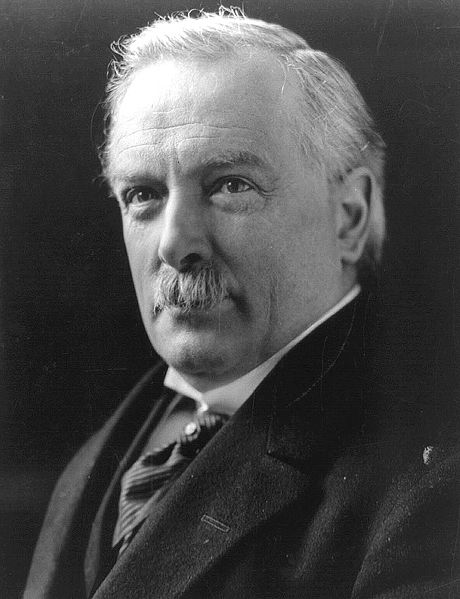

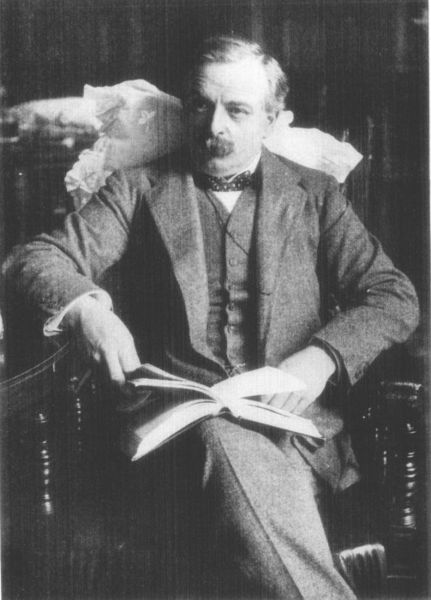

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom David Lloyd George, 1863

PAGE SPONSOR

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was a British statesman who was the first Welsh Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the only Prime Minister to have spoken English as a second language, Welsh having been his first.

During a long tenure of office, mainly as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he was a key figure in the introduction of many reforms which laid the foundations of the modern welfare state. He was the last Liberal to

be Prime Minister, as his coalition premiership was supported more by

Conservatives than by his own Liberals, and the subsequent split was a

key factor in the decline of the Liberal Party as a serious political

force. When he eventually became leader of the Liberal Party a decade

later he was unable to lead it back to power. He is best known as the

highly energetic Prime Minister (1916 – 1922) who guided the Empire

through the First World War to victory over Germany. He was a major player at the Paris Peace Conference of

1919 that reordered the world after the Great War. Lloyd George was a

devout evangelical and an icon of 20th century liberalism as the

founder of the welfare state. He is regarded as having made a greater

impact on British public life than any other 20th century leader,

thanks to his leadership of the war effort, his postwar role in

reshaping Europe, and his introduction of the welfare state before the

war. Born in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, Lloyd George was a Welsh-speaker and of Welsh descent and upbringing, the only Welshman ever to hold the office of Prime Minister of the British government.

In March 1863 his father William George, who had been a teacher in

Manchester and other cities, returned to his native Pembrokeshire because of failing health. He took up farming but died in June 1864 of pneumonia, aged 44. His mother Elizabeth George (1828 – 1896) sold the farm and moved with her children to her native Llanystumdwy, Caernarfonshire, where she lived in Tŷ Newydd

with

her brother Richard Lloyd (1834 – 1917), a strong Liberal. Lloyd

George's uncle was a towering influence on him, encouraging him to take

up a

career in law and enter politics;

his uncle remained influential up until his death at age 83 in February

1917, by which time his nephew was Prime Minister. He added his uncle's

surname to become "Lloyd George". His surname is usually given as

"Lloyd George" and sometimes as "George." His childhood showed through

in his entire career, as he attempted to aid the common man at the

expense of what he liked to call "the Dukes". However, his biographer John Grigg has

argued that George's childhood was nowhere near as poverty-stricken as

he liked to suggest, and that a great deal of his self-confidence came

from having been brought up by an uncle who enjoyed a position of

influence and prestige in his small community. Articled to a firm of solicitors in Porthmadog,

Lloyd George was admitted in 1884 after taking Honours in his final law

examination and set up his own practice in the back parlour of his

uncle's house in 1885. The practice flourished and he established

branch offices in surrounding towns, taking his brother William into

partnership in 1887. By then he was politically active, having

campaigned for the Liberal Party in the 1885 election, attracted by Joseph Chamberlain's "unauthorised programme" of reforms. The election resulted firstly in a stalemate, neither the Liberals nor the Conservatives having a majority, the balance of power being held by the Irish Parliamentary Party. William Gladstone's announcement of a determination to bring about Irish Home Rule later led to Chamberlain leaving the Liberals to form the Liberal Unionists.

Lloyd George was uncertain of which wing to follow, carrying a

pro-Chamberlain resolution at the local Liberal club and travelling to Birmingham planning to attend the first meeting of Chamberlain's National Radical Union,

but he had his dates wrong and arrived a week too early. In 1907, he

was to say that he thought Chamberlain's plan for a federal solution

correct in 1886 and still thought so, that he preferred the

unauthorised programme to the Whig-like platform of the official Liberal Party, and that had Chamberlain proposed solutions to Welsh grievances such as land reform and disestablishment, he, together with most Welsh Liberals, would have followed Chamberlain. On 24 January 1888 he married Margaret Owen, the daughter of a well-to-do local farming family. Also in that year he and other young Welsh Liberals founded a monthly paper Udgorn Rhyddid (Bugle of Freedom) and won on appeal to the Divisional Court of Queen's Bench the Llanfrothen burial case, which established the right of Nonconformists to

be buried according to their own denominational rites in parish burial

grounds, a right given by the Burial Act 1880 that had up to then been

ignored by the Anglican clergy. It was this case, which was hailed as a great victory throughout Wales, and his writings in Udgorn Rhyddid that led to his adoption as the Liberal candidate for Caernarfon Boroughs on 27 December 1888. In 1889 he became an Alderman on the Caernarfonshire County Council which had been created by the Local Government Act 1888. At that time he appeared to be trying to create a separate Welsh national party modelled on Parnell's Irish Parliamentary Party and worked towards a union of the North and South Wales Liberal Federations. Lloyd George was returned as Liberal MP for Carnarvon Boroughs — by a margin of 19 votes — on 13 April 1890 at a by-election caused by the death of the former Conservative member. He was the youngest MP in the House of Commons, and he sat with an informal grouping of Welsh Liberal members with a programme of disestablishing and disendowing the Church of England in Wales, temperance reform, and Welsh home rule. He would remain an MP until 1945, 55 years later. As

backbench members of the House of Commons were not paid at that time,

he supported himself and his growing family by continuing to practise

as a solicitor, opening an office in London under the title of Lloyd George and Co. and continuing in partnership with William George in Criccieth. In 1897 he merged his growing London practice with that of Arthur Rhys Roberts (who was to become Official Solicitor) under the title of Lloyd George, Roberts and Co. He

was soon speaking on Liberal issues (particularly temperance, the

"local option" and national as opposed to denominational education)

throughout England as well as Wales. During the next decade, Lloyd

George campaigned in Parliament largely on Welsh issues and in

particular for disestablishment and disendowment of the Church of

England. He wrote extensively for Liberal papers such as the Manchester Guardian.

When Gladstone retired after the defeat of the second Home Rule Bill in

1894, the Welsh Liberal members chose him to serve on a deputation to William Harcourt to

press for specific assurances on Welsh issues; when those were not

provided, they resolved to take independent action if the government

did not bring a bill for disestablishment. When that was not

forthcoming, he and three other Welsh Liberals (David Alfred Thomas, Herbert Lewis and Frank Edwards) refused the whip on 14 April 1892 but accepted Lord Rosebery's assurance and rejoined the official Liberals on 29 May. Thereafter, he devoted much time to setting up branches of Cymru Fydd (Young

Wales), which, he said, would in time become a force like the Irish

National Party. He abandoned this idea after being criticised in Welsh

newspapers for bringing about the defeat of the Liberal Party in the 1895 election and when, at a meeting in Newport on 16 January 1896, the South Wales Liberal Federation, led by David Alfred Thomas and Robert Bird moved that he be not heard. He gained national fame by his vehement opposition to the Second Boer War. He based his attack firstly on what were supposed to be the war aims – remedying the grievances of the Uitlanders and

in particular the claim that they were wrongly denied the right to

vote, saying "I do not believe the war has any connection with the

franchise. It is a question of 45% dividends" and that England (which

then did not have universal male suffrage) was more in need of

franchise reform than the Boer republics. His second attack was on the

cost of the war, which, he argued, prevented overdue social reform in

England, such as old age pensions and workmen's cottages. As the war

progressed, he moved his attack to its conduct by the generals, who, he

said (basing his words on reports by William Burdett-Coutts in The Times),

were not providing for the sick or wounded soldiers and were starving

Boer women and children in concentration camps. He reserved his major

thrusts for Chamberlain, accusing him of war profiteering through

the Chamberlain family company Kynochs Ltd, of which Chamberlain's

brother was Chairman and which had won tenders to the War Office though

its prices were higher than some of its competitors'; after speaking at

a meeting in Chamberlain's political base at Birmingham, he had to be

smuggled out disguised as a policeman, as his life was in danger from

the mob. At this time the Liberal Party was badly split as Herbert Henry Asquith, Richard Burdon Haldane and others were supporters of the war and formed the Liberal Imperial League. His

attacks on the government's Education Act, which provided that County

Councils would fund church schools, helped reunite the Liberals. His

successful amendment that the County need only fund those schools where

the buildings were in good repair served to make the Act a dead letter

in Wales, where the Counties were able to show that most Church of

England schools were in poor repair. Having already gained national

recognition for his anti-Boer War campaigns, his leadership of the

attacks on the Education Act gave him a strong parliamentary reputation

and marked him as a likely future cabinet member. In 1906 Lloyd George entered the new Liberal Cabinet of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman as President of the Board of Trade.

In that position he introduced legislation on many topics, from

Merchant Shipping and Companies to Railway regulation, but his main

achievement was in stopping a proposed national strike of the railway

unions by brokering an agreement between the unions and the railway

companies. While almost all the companies refused to recognise the

unions, Lloyd George persuaded the companies to recognise elected

representatives of the workers who sat with the company representatives

on conciliation boards — one for each company. If those boards

failed to agree then there was a central board. This was Lloyd George's

first great triumph for which he received praises from, among others, Kaiser Wilhelm II. Two weeks later, however, his great excitement was crushed by his daughter Mair's death from appendicitis. On Campbell-Bannerman's death he succeeded Asquith, who had become Prime Minister, as Chancellor of the Exchequer from

1908 to 1915. While he continued some work from the Board of

Trade — for example, legislation to establish a Port of London

authority and to pursue traditional Liberal programmes such as

licensing law reforms — his first major trial in this role was

over the 1908 – 1909 Naval Estimates. The Liberal manifesto at the 1906 general elections included a commitment to reduce military expenditure. Lloyd George strongly supported this, writing to Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty,

"the emphatic pledges given by all of us at the last general election

to reduce the gigantic expenditure on armaments built up by the

recklessness of our predecessors." He then proposed the programme be reduced from six to four dreadnoughts. This was adopted by the government but there was a public storm when the Conservatives, with covert support from the First Sea Lord Admiral Jackie Fisher,

campaigned for more with the slogan "We want eight and we won't wait".

This resulted in Lloyd George's defeat in Cabinet and the adoption of

estimates including provision for eight dreadnoughts. This was later to

be said to be one of the main turning points in the naval arms race

between Germany and Britain that contributed to the outbreak of World War I. Although

old-age pensions had already been introduced by Asquith as Chancellor,

Lloyd George was largely responsible for the introduction of state

financial support for the sick and infirm (known colloquially as "going

on the Lloyd George" for decades afterwards) — legislation often

referred to as the Liberal reforms.

In 1909

he introduced his famous budget imposing increased taxes on luxuries,

liquor, tobacco, incomes, and land, so that money could be made

available for the new welfare programs as well as new battleships. The

nation's landowners (well represented in the House of Lords) were

intensely angry at the new taxes. In the House of Commons Lloyd George

gave a brilliant defense of the budget, which was attacked by the

Conservatives. On the stump, most famously in his Limehouse speech, he

denounced the Conservatives and the wealthy classes with all his very

considerable oratorical power. The budget passed the Commons, but was

defeated by the Conservative majority in the House of Lords. The

elections of 1910 upheld the Liberal government and the budget finally

passed the Lords. Subsequently, the Parliament Bill for social reform

and Irish Home Rule, which Lloyd George strongly supported, was passed

and the veto power of the House of Lords was greatly curtailed. In 1911

Lloyd George succeeded in putting through Parliament his National

Insurance Act, making provision for sickness and invalidism, and this

was followed by his Unemployment Insurance Act. These social reforms

began in Britain the creation of a welfare state and fulfilled in both

countries the aim of dampening down the demands of the growing working

class for rather more radical solutions to their impoverishment.

In 1913 Lloyd George, along with Attorney-General Rufus Isaacs, was involved in the Marconi scandal.

Accused of speculating in Marconi shares on the inside information that

they were about to be awarded a key government contract (which would

have caused them to increase in value), he told the House of Commons

that he had not speculated in the shares of "that company", which was

not the whole truth as he had in fact speculated in shares of Marconi's

American sister company. This scandal, which would have destroyed his

career if the whole truth had come out at the time, was a precursor to

the whiff of corruption (e.g. the sale of honours) that later

surrounded Lloyd George's premiership. Lloyd George was considered an opponent of war until the Agadir Crisis of 1911, when he had made a speech attacking German aggression. Nevertheless, he supported World War I when it broke out, not least as Belgium, for whose defence Britain was supposedly fighting, was a "small nation" like Wales or indeed the Boers. For

the first year of the war he remained chancellor of the exchequer, but

when the shortage of the English supply of munitions was revealed and

the cabinet was reconstituted as the first coalition ministry in May 1915, Lloyd George was made Minister of Munitions in

charge of the newly created Ministry of Munitions. In this position he

was a brilliant success, but he was not at all satisfied with the

progress of the war, and late in 1915 he became a strong supporter of

general conscription. He put through the conscription act of 1916, and

in June 1916 he became Secretary of State for War.

The weakness of Asquith as a planner and organiser was underscored as

the war plans did not work well. Asquith, who was forced out in

December 1916 and Lloyd George unexpectedly became Prime Minister, with

the nation demanding he take charge of the war in vigorous fashion. In

1916, Asquith was replaced as Prime Minister, splitting the Liberal

Party into two factions: those who supported him and those who

supported the coalition government. His support from the Unionists was

critical. After 6 December 1916, Lloyd George was dependent on the support of Conservatives and of the press baron Lord Northcliffe (who owned both The Times and The Daily Mail)

for his continuance in power. This was reflected in the make-up of his

five-member war cabinet, which as well as himself included the

Conservative Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of

Lords, Lord Curzon; Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons, Andrew Bonar Law; and Minister without Portfolio, Lord Milner. The fifth member, Arthur Henderson, was the unofficial representative of the Labour Party.

This accounts for Lloyd George's inability to establish complete

personal control over military strategy, as Churchill did in the Second

World War, and also for his reluctance to put his foot down and demand

a halt to the Passchendaele Offensive of

autumn 1917. Nevertheless, Lloyd George engaged in almost constant

intrigues to reduce the power of the generals, including trying to

subordinate British forces in France to the French General Nivelle in spring 1917, sending forces to Italy and Palestine, and in the winter of 1917/18 securing the resignations of both the service chiefs, Admiral Jellicoe and General Robertson. In December 1917, Lloyd George remarked to C.P. Scott that:

"If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of

course they don't know, and can't know." Nevertheless the War Cabinet

was a very successful innovation. It met almost daily, with Sir Maurice Hankey as

secretary, and made all major political, military, economic and

diplomatic decisions. Rationing was finally imposed in early 1918 for

meat, sugar and fats (butter and oleo) – but not bread; the new

system worked smoothly. From 1914 to 1918 trade-union membership doubled, from a little over four million to a little over eight

million. Work stoppages and strikes became frequent in 1917–18 as the

unions expressed grievances regarding prices, liquor control, pay

disputes, "dilution," fatigue from overtime and from Sunday work, and

inadequate housing. Conscription put

into uniform nearly every physically fit man, six million out of ten

million eligible. Of these about 750,000 lost their lives and 1,700,000

were wounded. Most deaths were of young unmarried men; however, 160,000

wives lost husbands and 300,000 children lost fathers. Most of the organisations Lloyd George created during World War I were replicated with the outbreak of World War II. As Lord Beaverbrook remarked, "There were no signposts to guide Lloyd George." In 1903, after the Kishinev Pogrom, Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain offered the Zionist Movement the possibility of settling in Uganda. Lloyd George represented the movement in drafting an agreement with the

government; however, the issue was controversial for both sides, and

the proposal was eventually voted down by the Zionist movement at a

special convention. In 1917, one of Lloyd George's first acts as Prime Minister was to order the attack on the Ottoman Empire and the conquest of Palestine. Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour issued his famous Declaration in favour of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people". Lloyd George played a critical role in this announcement. At the end of the war Lloyd George's reputation stood at its zenith. A leading Conservative said "He can be dictator for life if he wishes." In the "Coupon election" of 1918 he

declared this must be a land "fit for heroes to live in." He did not

say, "We shall squeeze the German lemon until the pips squeak" (that was Sir Eric Geddes), but he did express that sentiment about reparations from Germany to pay the entire cost of the war, including pensions. At Bristol,

he said that German industrial capacity "will go a pretty long way." We

must have "the uttermost farthing," and "shall search their pockets for

it." As the campaign closed, he summarised his programme: His

"National Liberal" coalition won a massive landslide, winning 525 of

the 707 contests; however, the Conservatives had control within the

Coalition of more than two-thirds of its seats. Asquith's independent

Liberals were crushed and emerged with only 33 seats, falling behind

Labour (their parliamentary leadership was briefly taken over by the

unknown Donald Maclean until Asquith, who, like the other leading Liberals, had lost his own seat, returned to the House at a by-election).

Lloyd George represented Britain at the Versailles Peace Conference, clashing with French Premier Georges Clemenceau, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando.

Lloyd George wanted to punish Germany politically and economically for

devastating Europe during the war, but did not want to utterly destroy

the German economy and political system the way Clemenceau and many

other people of France wanted to do with their demand for massive

reparations. Memorably, he replied to a question as to how he had done

at the peace conference, "Not badly, considering I was seated between Jesus Christ and Napoleon". The British economist John Maynard Keynes attacked Lloyd George's stance on reparations in his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace, calling the Prime Minister a "half-human visitor to our age from the hag-ridden magic and enchanted woods of Celtic antiquity". In Poland his

position is controversial, it being believed that he had saved that

country from the Bolsheviks but he was also vilified in Poland during

1919–20 for his supposed opinion that Poles were "children who gave

trouble".

A substantive programme of social reform was introduced under his government. The Education Act 1918 raised the school leaving age to 14 and increased the powers and duties of the Board of Education. The Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 provided subsides for house building by local authorities. A total of 170000 homes were built under this Act. The Unemployment Insurance Act 1920 extended national insurance to 11 million additional workers. However, the reform was substantially rolled back by the Geddes Axe, which cut public expenditure by £76 million, including substantial cuts to education.

Lloyd

George began to feel the weight of the coalition with the Conservatives

after the war. His decision to extend conscription to Ireland in 1917 had been disastrous, leading to the wipeout of the old Irish Home Rule Party at the 1918 election, replaced by Sinn Féin MPs who immediately declared independence. Lloyd George presided over the Anglo-Irish War, which led to the negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty with Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins and the formation of the Irish Free State. At one point, he famously declared of the IRA,

"We have murder by the throat!" However he was soon to begin

negotiations with IRA leaders to recognise their authority and end the

conflict. Lloyd

George's coalition was too large, and deep fissures quickly emerged.

The more traditional wing of the Unionist Party had no intention of

introducing these reforms, which led to three years of frustrated

fighting within the coalition both between the National Liberals and

the Unionists and between factions within the Conservatives themselves.

It was this fighting, coupled with the increasingly differing

ideologies of the two forces in a country reeling from the costs of

war, that led to Lloyd George's fall from power. In June 1922

Conservatives were able to show that he had been selling knighthoods and peerages — and the OBE which

was created at this time — for money. Conservatives were concerned

by his desire to create a party from these funds comprising moderate Liberals and Conservatives. A major attack in the House of Lords followed on his corruption resulting in the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act 1925. The Conservatives also attacked Lloyd George as lacking any executive accountability as Prime Minister, claiming that he never turned up to Cabinet meetings and banished some government departments to the gardens of 10 Downing Street. However it was not until 19 October 1922 that the coalition was dealt its final blow. After criticism of Lloyd George over the Chanak crisis mounted, Conservative leader Austen Chamberlain summoned a meeting of Conservative Members of Parliament at the Carlton Club to

discuss their attitude to the Coalition in the forthcoming election.

They sealed Lloyd George's fate with a vote of 187 to 87 in favour of

abandoning the coalition. Chamberlain and other Conservatives such as

the Earl of Balfour argued for supporting Lloyd George, while former party leader Andrew Bonar Law argued the other way, claiming that breaking up the coalition "wouldn't break Lloyd George's heart". The main attack came from Stanley Baldwin,

then President of the Board of Trade, who spoke of Lloyd George as a

"dynamic force" who would break the Conservative Party. Baldwin and

many of the more progressive members of the Conservative Party

fundamentally opposed Lloyd George and those who supported him on moral

grounds. A motion was passed that the Conservative Party should fight

the next election on its own for the first time since the start of

World War I. Throughout

the 1920s Lloyd George remained a dominant figure in British politics,

being frequently predicted to return to office but never succeeding; this period of his life is covered in John Campbell's book The Goat in the Wilderness. Before the 1923 election, he resolved his dispute with Asquith, allowing the Liberals to run a united ticket against Stanley Baldwin's policy of tariffs (although

there was speculation that Baldwin had adopted such a policy in order

to forestall Lloyd George from doing so). At the 1924 general election, Baldwin won a clear victory, the leading coalitionists such as Austen Chamberlain and Lord Birkenhead (and former Liberal Winston Churchill) agreeing to serve under Baldwin and thus ruling out any restoration of the 1916–22 coalition. In

1926 Lloyd George succeeded Asquith as Liberal leader. Although since

the disastrous election result in 1924 the Liberals were now very much

the third party in British politics, Lloyd George was able to release

money from his fund to finance candidates and ideas for public works to

reduce unemployment (as detailed in pamphlets such as the "Yellow Book"

and the "Green Book"). However, the results at the 1929 general

election were disappointing: the Liberals increased their support only

to 60 or so seats, while Labour became the largest party for the first

time. Once again, the Liberals ended up supporting a minority Labour

government. In 1929 Lloyd George became Father of the House, the longest serving member of the Commons. In 1931 an illness prevented his joining the National Government when

it was formed. Later when the National Government called a General

Election he tried to pull the Liberal Party out of it but succeeded in

taking only a few followers, most of whom were related to him; the main

Liberal party remained in the coalition for a year longer, under the

leadership of Sir Herbert Samuel.

By the 1930s Lloyd George was on the margins of British politics,

although still intermittently in the public eye and publishing his War

Memoirs. In 1934 Lloyd George made a controversial statement about reserving the right to "bomb niggers" that has since been quoted by political activist Noam Chomsky and others. The

quote was originally attributed to Lloyd George in 1934 by Frances

Stevenson, his secretary and second wife, in her diary, which was

published in 1971. On page 259 of Lloyd George: A Diary by Frances Stevenson,

the 9 March 1934 diary entry includes the following passage: "Debate

last night in the House on Air — strong demonstrations in favour

of increased no. of fighting planes. D. [David Lloyd George] says it

could have been avoided but for Simon's [Sir John Simon's]

mismanagement. At Geneva other countries would have agreed not to use aeroplanes for bombing purposes,

but we insisted on reserving the right, as D. puts it, to bomb niggers!

Whereupon the whole thing fell through, & we add 5 millions to our

air armaments expenditure." British

historian V.G. Kiernan wrote that Lloyd George and others in the

British government had argued during that period for the right to bomb

British colonies as they deemed it necessary. On

17 January 1935 Lloyd George sought to promote a radical programme of

economic reform, called "Lloyd George's New Deal" after the American New Deal.

However the programme did not find favour in the mainstream political

parties. Later that year Lloyd George and his family reunited with the

Liberal Party in Parliament. In March 1936 Lloyd George met Adolf Hitler at the Berghof in Berchtesgaden and offered some public comments that were surprisingly favourable to the German dictator,

expressing warm enthusiasm both for Hitler personally and for Germany's

public works schemes (upon returning, he wrote of Hitler in the Daily Express as "the greatest living German", "the George Washington of Germany"). Despite this embarrassment, however, as the 1930s progressed Lloyd George became more clear-eyed about the Nazi threat and joined Winston Churchill,

among others, in fighting the government's policy of appeasement. In

the late 1930s he was sent by the British government to try to dissuade

Hitler from his plans of Europe-wide expansion. In perhaps the last

important parliamentary intervention of his career, which occurred

during the crucial Norway Debate of May 1940, Lloyd George made a powerful speech that helped to undermine Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister and to pave the way for the ascendancy of Churchill as Premier. Churchill

offered Lloyd George a place in his Cabinet but he refused, citing his

dislike of Chamberlain. Lloyd George also thought that Britain's

chances in the war were dim, and he remarked to his secretary: "I shall

wait until Winston is bust". He wrote to the Duke of Bedford in September 1940 advocating a negotiated peace with Germany after the Battle of Britain. A pessimistic speech by Lloyd George on 7 May 1941 led Churchill to compare him with Philippe Pétain.

On 11 June 1942 he made his last-ever speech in the House of Commons,

and he cast his last vote in the Commons on 18 February 1943 as one of

the 121 MPs (97 Labour) condemning the Government for its failure to

back the Beveridge Report. Fittingly, his final vote was in defence of the welfare state which he had helped to create. He enjoyed listening to the broadcasts of William Joyce.

Increasingly in his late years his characteristic political courage

gave way to physical timidity and hypochondria. He continued to attend

Castle Street Baptist Chapel in London, and to preside over the national eisteddfod at

its Thursday session each summer. At the end, he returned to Wales. In

September 1944, he and Frances left Churt for Tŷ Newydd, a farm near

his boyhood home in Llanystumdwy. He was now weakening rapidly and his

voice failing. He was still an MP but had learned that wartime changes

in the constituency meant that Caernarfon Boroughs might go

Conservative at the next election. On New Years Day 1945 Lloyd George was raised to the peerage as Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor and Viscount Gwynedd, of Dwyfor in the County of Caernarvonshire.

Under the rules governing titles within the peerage, Lloyd George's

name in his title was hyphenated even though his surname was not. He died of cancer on 26 March 1945, aged 82, without ever taking up his seat in the House of Lords, his wife Frances and his daughter Megan at the bedside. Four days later, on Good Friday, he was buried beside the River Dwyfor in Llanystumdwy. A great boulder marks his grave; there is no inscription. However a monument designed by the architect Sir Clough Williams-Ellis was subsequently erected around the grave, bearing an englyn (strict-metre

stanza) engraved on slate in his memory composed by his nephew Dr

William George. Nearby stands the Lloyd George Museum, also designed by

Williams-Ellis and opened in 1963. On

20 January 1941, his wife died; Lloyd George was deeply upset by the

fact that bad weather prevented him from being with her when she died.

In October 1943, aged 80, and to the disapproval of his children, he

married his secretary and mistress, Frances Stevenson. He had been involved with Stevenson for three decades by then. The

first Countess Lloyd-George is now largely remembered for her diaries,

which dealt with the great issues and statesmen of Lloyd George's

heyday. A volume of Lloyd George's letters to her, "My Darling Pussy", has also been published, the editor A.J.P. Taylor pointing

out that Lloyd George's nickname for Frances referred to her gentle

personality. The 2nd marriage caused severe tension between Lloyd

George and his children by his first wife. He

had five children by his first wife — Richard (1889 – 1968), Mair

(1890 – 1907), Olwen (1892 – 1990), Gwilym (1894 – 1967) and Megan

(1902 – 1966) — and one child by Stevenson, a daughter named

Jennifer (born 1929). His son, Gwilym, and daughter, Megan,

both followed him into politics and were elected members of parliament.

They were politically faithful to their father throughout his life but

following their father's death each drifted away from the Liberal

Party, Gwilym finishing his career as a Conservative Home Secretary while Megan became a Labour MP in 1957, perhaps symbolising the fate of much of the old Liberal Party. Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan, who detailed Lloyd George's role in the 1919 peace conference in her book, Paris 1919, is his great-granddaughter. The British television presenter Dan Snow is his great-great-grandson, as is the Internet usability

guru Bryn Williams. Other descendants include Owen, 3rd Earl

Lloyd-George, who is his grandson, and his son Robert (the chairman of

Lloyd George Management).