<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, 1689

- Actor Oliver Hardy, 1892

- 1st Prime Minister of Australia Sir Edmund Barton, 1849

PAGE SPONSOR

Oliver Hardy (born Norvell Hardy; January 18, 1892 – August 7, 1957) was an American comic actor famous as one half of Laurel and Hardy, the classic double act that began in the era of silent films and lasted over 31 years, from 1926 to 1957.

His father, Oliver, was a Confederate veteran wounded at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. After his demobilization as a recruiting officer for Company K, 16th Georgia Regiment, the elder Oliver Hardy assisted his father in running the vestiges of the family cotton plantation, bought a share in a retail business and was elected full-time Tax Collector for Columbia County. His mother, Emily Norvell, the daughter of Thomas Benjamin Norvell and Mary Freeman, was descended from Captain Hugh Norvell of Williamsburg, Virginia. Her family arrived in Virginia before 1635. Their marriage took place on March 12, 1890; it was the second marriage for the widow Emily, and the third for Oliver. The family moved to Madison in 1891, before Norvell’s birth. Norvell’s mother owned a house in Harlem, which was either empty or tenanted by her mother. It is probable that Norvell was born in Harlem, though some sources say it was in his mother’s home town, Covington. His father died less than a year after his birth. Hardy was the youngest of five. As a child, Hardy was sometimes difficult. He was sent to a Milledgeville military academy as a youngster. In the 1905/1906 school year, fall semester (September - January), when he was 13, Hardy was sent to Young Harris College in north Georgia. However, he was in the junior high component of that institution (the equivalent of high school today), not the two-year college which exists today.

He had little interest in education, although he acquired an early interest in music and theater, possibly from his mother’s tenants. He joined a theatrical group, and later ran away from a boarding school near Atlanta to sing with the group. His mother recognized his talent for singing, and sent him to Atlanta to study music and voice with singing teacher Adolf Dahm Patterson, but Hardy skipped some of his lessons to sing in the Alcazar Theater, a cinema, for US$3.50 a week. He subsequently decided to go back to Milledgeville.

Sometime prior to 1910, Hardy began styling himself "Oliver Norvell Hardy", with the first name “Oliver” being added as a tribute to his father. He appears as “Oliver N. Hardy” in the 1910 U.S. census, and in all future legal records, marriage announcements, etc., Hardy uses “Oliver” as his first name.

Hardy’s mother wanted him to attend the University of Georgia in

the fall of 1912, to study law, but there is no evidence that he ever

did or did not. In 1910, a movie theater opened in Hardy’s home town of Milledgeville, and he became the projectionist, ticket taker, janitor and manager.

He soon became obsessed with the new motion picture industry, and

became convinced that he could do a better job than the actors he saw

on the screen. A friend suggested that he move to Jacksonville, Florida, where some films were being made. In 1913, he did just that, where he worked as a cabaret and vaudeville singer at night, and at the Lubin Studios during the day. It was at this time that he met and married his first wife, pianist Madelyn Saloshin. The next year he made his first movie, Outwitting Dad,

for the Lubin studio. He was billed as O.N. Hardy, taking his father’s

name as a memorial. In his personal life, he was known as “Babe” Hardy,

a nickname that he was given by an Italian barber, who would apply talcum powder to

Oliver’s cheeks and say, “nice-a-bab-y.” In many of his later films at

Lubin, he was billed as “Babe Hardy.” Hardy was a big man at six feet,

one inch tall and weighed up to 300 pounds. His size placed limitations

on the roles he could play. He was most often cast as “the heavy” or

the villain. He also frequently had roles in comedy shorts, his size

complementing the character. By 1915, he had made 50 short one-reeler films at the Lubin studio. He later moved to New York and made films for the Pathé, Casino and Edison Studios. He then returned to Jacksonville and made films for the Vim and King Bee studios. He worked with Charlie Chaplin imitator Billy West and

comedic actress Ethel Burton Palmer during this time. (Hardy continued

playing the “heavy” for West well into the early 1920s, often imitating Eric Campbell to

West’s Chaplin.) In 1917, Oliver Hardy moved to Los Angeles, working

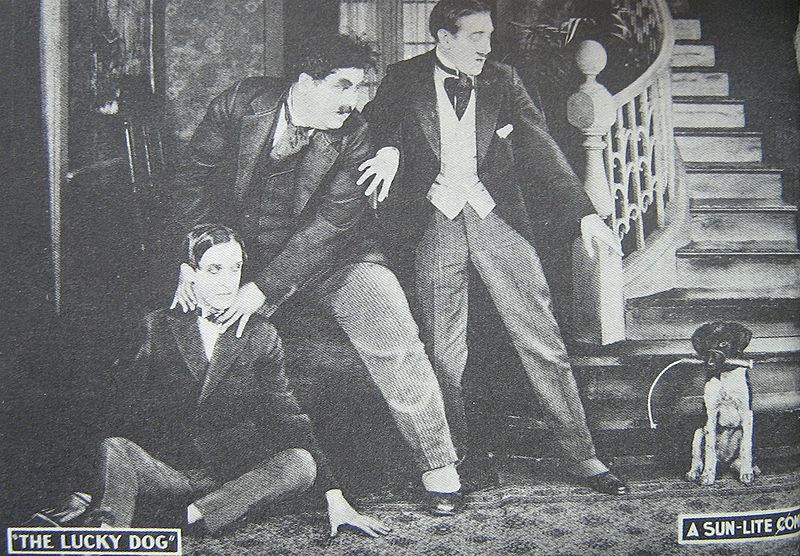

freelance for several Hollywood studios. Later that year, he appeared

in the movie The Lucky Dog, produced by G.M. (“Broncho Billy”) Anderson and starring a young British comedian named Stan Laurel. Oliver Hardy played the part of a robber, trying to stick up Stan’s character. They did not work together again for several years. Between 1918 and 1923, Oliver Hardy made more than forty films for Vitagraph, mostly playing the “heavy” for Larry Semon. In 1919, he separated from his wife, ending with a divorce in

1920, allegedly due to Babe’s infidelity. The very next year, on

November 24, 1921, Babe married again, to actress Myrtle Reeves. This

marriage was also unhappy and Myrtle eventually became an alcoholic. In 1924, Hardy began working at Hal Roach Studios working with the Our Gang films and Charley Chase. In 1925, he starred as the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz. Also that year he was in the film, Yes, Yes, Nanette!, starring Jimmy Finlayson, who in later years was a recurring character in the Laurel and Hardy film series. The film was directed by Stan Laurel. He also continued playing supporting roles in films featuring Clyde Cooke and Bobby Ray. In 1926, Hardy was scheduled to appear in Get ’Em Young but

was unexpectedly hospitalized after being burned by a hot leg of lamb.

Laurel, who had been working as a gag man and director at Roach

Studios, was recruited to fill in. Laurel kept appearing in front of the camera rather than behind it, and later that year appeared in the same movie as Hardy, 45 Minutes from Hollywood, although they didn’t share any scenes together. In 1927, Laurel and Hardy began sharing screen time together in Slipping Wives, Duck Soup (no relation to the 1933 Marx Brothers’ film of the same name) and With Love and Hisses. Roach Studios’ supervising director Leo McCarey,

realizing the audience reaction to the two, began intentionally teaming

them together, leading to the start of a Laurel and Hardy series late

that year. With this pairing, he created arguably the most famous double act in movie history. They began producing a huge body of short movies, including The Battle of the Century (1927) (with one of the largest pie fights ever filmed), Should Married Men Go Home? (1928), Two Tars (1928), Unaccustomed As We Are (1929, marking their transition to talking pictures) Berth Marks (1929), Blotto (1930), Brats (1930)

(with Stan and Ollie portraying themselves, as well as their own sons,

using oversized furniture to sets for the ‘young’ Laurel and Hardy), Another Fine Mess (1930), Be Big! (1931), and many others. In 1929, they appeared in their first feature, in one of the revue sequences of Hollywood Revue of 1929 and the following year they appeared as the comic relief in a lavish all-color (in Technicolor) musical feature entitled: The Rogue Song. This film marked their first appearance in color. In 1931, they made their first full length movie (in which they were the actual stars), Pardon Us although they continued to make features and shorts until 1935. Perhaps their greatest achievement, however, was The Music Box (1932), which won them an Academy Award for best short film — their only such award. In

1936, Hardy’s personal life suffered a blow as he and Myrtle divorced.

While waiting for a contractual issue between Laurel and Hal Roach to

be resolved, Hardy made Zenobia with Harry Langdon. Eventually, however, new contracts were agreed and the team was loaned out to General Services Studio to make The Flying Deuces.

While on the lot, Hardy fell in love with Virginia Lucille Jones, a

script girl, whom he married the next year. They enjoyed a happy,

successful marriage until his death. Laurel and Hardy also began performing for the USO, supporting the Allied troops during World War II. They also made A Chump at Oxford (1940) (which features a moment of role reversal, with Oliver becoming a temporarily concussed subordinate to Stan) and Saps at Sea (1940). In the early 1940s, Laurel and Hardy left Roach Studios and began making films for 20th century Fox, and later MGM.

Although they were financially better off, they had very little

artistic control at the large studios, and hence the films lack the

very qualities that had made Laurel and Hardy worldwide names. In

1947, Laurel and Hardy went on a six week tour of Great Britain.

Initially unsure of how they would be received, they were mobbed

wherever they went. The tour was then lengthened to include engagements

in Scandinavia, Belgium, France, as well as a Royal Command Performance for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

Biographer John McCabe said they continued to make live appearances in

the United Kingdom and France for the next several years, until 1954,

often using new sketches and material that Laurel had written for them. In 1949, Hardy’s friend, John Wayne, asked him to play a supporting role in The Fighting Kentuckian. Hardy had previously worked with Wayne and John Ford in a charity production of the play What Price Glory? while

Laurel began treatment for his diabetes a few years previously.

Initially hesitant, Hardy accepted the role at the insistence of his

comedy partner. Frank Capra later invited Hardy to play a cameo role in Riding High with Bing Crosby in 1950. In 1950—51, Laurel and Hardy made their final film. Atoll K (also known as Utopia)

was a simple concept; Laurel inherits an island, and the boys set out

to sea, where they encounter a storm and discover a brand new island,

rich in uranium,

making them powerful and wealthy. However, it was produced by a

consortium of European interests, with an international cast and crew

that could not speak to each other. In addition, the script needed

to be rewritten by Stan to make it fit the comedy team’s style, and

both suffered serious physical illness during the filming. In

1955, the pair had contracted with Hal Roach, Jr., to produce a series

of TV shows based on the Mother Goose fables. They would be filmed in

color for NBC. However, this was never to be. Laurel suffered a stroke, which required a lengthy convalescence. Hardy had a heart attack and stroke later that year, from which he never physically recovered. In

May 1954, Hardy suffered a mild heart attack. During 1956, Hardy began

looking after his health for the first time in his life. He lost more

than 150 pounds in a few months which completely changed his

appearance. Letters written by Stan Laurel,

however, mention that Hardy had terminal cancer, which has caused some

to suspect that this was the real reason for Hardy’s rapid weight loss. Hardy

suffered a major stroke on September 14, which left him confined to bed

and unable to speak for several months. He remained at home, in the

care of his beloved Lucille. He suffered two more strokes in early

August 1957, and slipped into a coma from which he never recovered. Oliver Hardy died on August 7, 1957, aged 65 years old. His remains are located in the Masonic Garden of Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in North Hollywood. In 2006, BBC Four showed a drama called Stan based on Laurel meeting Hardy on his deathbed and reminiscing about their career. Although based on fact, it took great liberties with both the events and main characters.

Hardy’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 1500 Vine Street, Hollywood, California.