<Back to Index>

- Physicist Paul Langevin, 1872

- Painter Édouard Manet, 1832

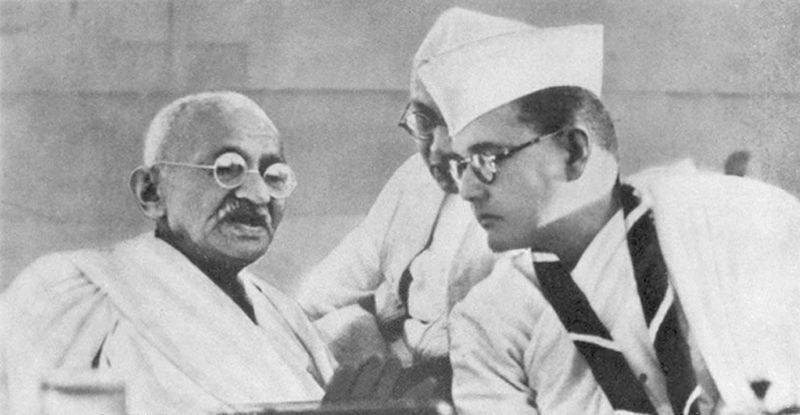

- President of the Indian National Congress Subhas Chandra Bose, 1897

PAGE SPONSOR

Subhas Chandra Bose (born 23 January 1897; presumed to have died 18 August 1945, although this is disputed), popularly known as Netaji (literally "Respected Leader"), was one of the greatest leaders in the Indian independence movement.

Bose

advocated complete freedom for India at the earliest, whereas the

Congress Committee wanted it in phases, through a Dominion status.

Other younger leaders including Jawaharlal Nehru supported Bose and

finally at the historic Lahore Congress convention, the Congress had to

adopt Purna Swaraj (complete freedom) as its motto. Bhagat Singh's martyrdom and the inability of the Congress leaders to save his life infuriated Bose and he started a movement opposing the Gandhi-Irwin Pact.

He was imprisoned and expelled from India. But defying the ban, he came

back to India and was imprisoned again. Bose was elected president of

the Indian National Congress for two consecutive terms, but had to resign from the post following ideological conflicts with Mahatma Gandhi and

after openly attacking the Congress' foreign and internal policies.

Bose believed that Mahatma Gandhi's tactics of non-violence would never

be sufficient to secure India's independence, and advocated violent

resistance. He established a separate political party, the All India Forward Bloc and

continued to call for the full and immediate independence of India from

British rule. He was imprisoned by the British authorities eleven

times. His famous motto was "Give me blood and I will give you freedom". His stance did not change with the outbreak of the Second World War,

which he saw as an opportunity to take advantage of British weakness.

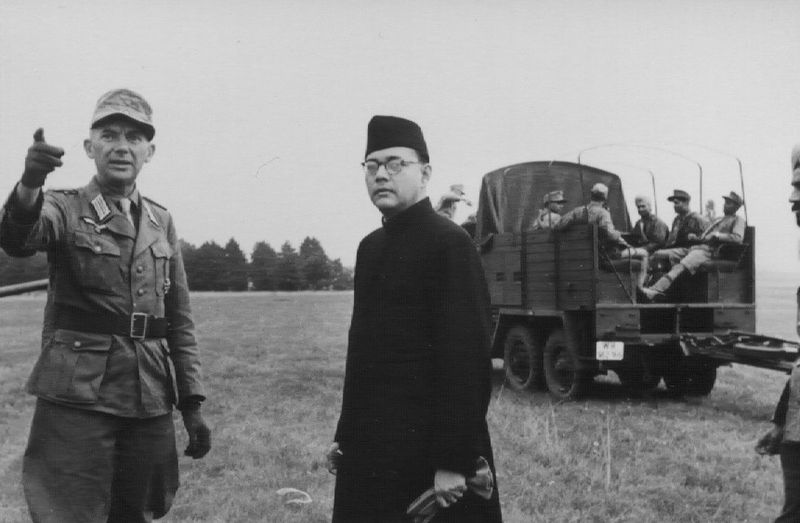

At the outset of the war, he left India, travelling to the Soviet Union, Germany and Japan,

seeking an alliance with the aim of attacking the British in India.

With Japanese assistance, he re-organised and later led the Azad Hind Fauj or Indian National Army, formed from Indian prisoners of war and plantation workers from British Malaya, Singapore, and other parts of Southeast Asia, against British forces. With Japanese monetary, political, diplomatic and military assistance, he formed the Azad Hind Government in exile, regrouped and led the Indian National Army in battle against the allies at Imphal and in Burma. His political views and the alliances he made with Nazi and

other militarist regimes at war with Britain have been the cause of

arguments among historians and politicians, with some accusing him of

fascist sympathies, while others in India have been more sympathetic

towards the inculcation of realpolitik as a manifesto that guided his social and political choices.He is presumed to have died on 18 August 1945 in a plane crash over Taiwan. However, contradictory evidence exists regarding his death in the accident. Subhash Chandra Bose was born in a Bengali Kayasth family on January 23, 1897 in Cuttack (Odia Bazar), Orissa,

the ninth child among 14, of Janakinath Bose, an advocate, and

Prabhavati Devi. Bose studied in an Anglo school at Cuttack until

standard 6 which is now known as Stewart School and then shifted to

Ravenshaw Collegiate School of Cuttack. A brilliant student, Bose

topped the matriculation examination of Calcutta province in 1911 and

passed his B.A. in 1918 in Philosophy from the Scottish Church College of the University of Calcutta. Bose went to study in Fitzwilliam Hall of the University of Cambridge,

and his high score in the Civil Service examinations meant an almost

automatic appointment. He then took his first conscious step as a

revolutionary and resigned the appointment on the premise that the

"best way to end a government is to withdraw from it". At the time,

Indian nationalists were shocked and outraged because of the Amritsar massacre and the repressive Rowlatt legislation of 1919. Returning to India, Bose wrote for the newspaper Swaraj and took charge of publicity for the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee. His mentor was Chittaranjan Das, spokesman for aggressive nationalism in Bengal. Bose worked for Das when the latter was elected mayor of Calcutta in

1924. In a roundup of nationalists in 1925, Bose was arrested and sent

to prison in Mandalay, where he contracted tuberculosis Released from prison two years later, Bose became general secretary of the Congress party and worked with Jawaharlal Nehru for independence. Again Bose was arrested and jailed for civil disobedience; this time he emerged Mayor of Calcutta. During the mid 1930s Bose traveled in Europe, visiting Indian students and European politicians, as well as Hitler in 1942. He observed party organization and saw communism and fascism in action. By

1938 Bose had become a leader of national stature and agreed to accept

nomination as Congress president. He stood for unqualified Swaraj (independence), including the use of force against the British. This meant a confrontation with Mohandas Gandhi, who in fact opposed Bose's presidency, splitting the Congress party.

Bose attempted to maintain unity, but Gandhi advised Bose to form his

own cabinet. The rift also divided Bose and Nehru. Bose appeared at the

1939 Congress meeting on a stretcher. Though he was elected president

again, over Gandhi's preferred candidate Pattabhi Sitaramayya,

U Muthuramalingam Thevar strongly supported Bose in the intra-Congress

dispute. Thevar mobilised all south India votes for Bose. However, due

to

the manoeuvrings of the Gandhi-led clique in the Congress Working

Committee, Bose found himself forced to resign from the Congress

Presidency. His uncompromising stand finally cut him off from the

mainstream of Indian nationalism. Bose then organized the Forward Bloc on

June 22, aimed at consolidating the political left, but its main

strength was in his home state, Bengal. U Muthuramalingam Thevar, who

was disillusioned by the official Congress leadership which had not

revoked the CTA, joined the Forward Bloc. When Bose visited Madurai on

September 6, Thevar organised a massive rally as his reception. Bose

advocated the approach that the political instability of war-time

Britain should be taken advantage of — rather than simply wait for the

British to grant independence after the end of the war (which was the

view of Gandhi, Nehru and a section of the Congress leadership at the

time). In this, he was influenced by the examples of Italian statesmen

Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini. His

correspondence reveals that despite his clear dislike for British

subjugation, he was deeply impressed by their methodical and systematic

approach and their steadfastly disciplinarian outlook towards life. In

England, he exchanged ideas on the future of India with British Labour

Party leaders and political thinkers like Lord Halifax, George

Lansbury, Clement Attlee, Arthur Greenwood, Harold Laski, J.B.S.

Haldane, Ivor Jennings, G.D.H. Cole, Gilbert Murray and Sir Stafford

Cripps . He came to believe that a free India needed Socialist

authoritarianism, on the lines of Turkey's Kemal Atatürk, for at

least two decades. Bose was refused permission by the British

authorities to meet Mr. Ataturk at Ankara for political reasons. It

should be noted that during his sojourn in England, only the Labour

Party and Liberal politicians agreed to meet with Bose when he tried to

schedule appointments. Conservative Party officials refused to meet

Bose or show him the slightest courtesy due to the fact that he was a

politician coming from a colony, but it may also be recalled that in

the 1930s leading figures in the Conservative Party had opposed even

Dominion status for India. It may also be observed here that it was

during the regime of the Labour Party (1945 - 1951), with Attlee as the

Prime Minister, that India gained independence. On

the outbreak of war, Bose advocated a campaign of mass civil

disobedience to protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's decision to

declare war on India's behalf without consulting the Congress

leadership. Having failed to persuade Gandhi of the necessity of this,

Bose organised mass protests in Calcutta calling for the 'Holwell

Monument' commemorating the Black Hole of Calcutta, which then stood at

the corner of Dalhousie Square, to be removed. A

reasonable measure of the contrast between Gandhi and Bose is captured

in a saying attributable to him: "If people slap you once, slap them

twice". He was thrown in jail by the British, but was released

following a seven-day hunger strike. Bose's house in Calcutta was kept

under surveillance by the CBI, but their vigilance left a good deal to

be desired. With two court cases pending, he felt the British would not

let him leave the country before the end of the war. This set the scene

for Bose's escape to Germany, via Afghanistan and the Soviet Union.On

the night of his escape he dressed as a pathan left his house under

strict observation. Bose had never been to Afghanistan, and could not

speak the local tribal language (Pashto). Bose

escaped from under British surveillance at his house in Calcutta. On

January 19, 1941, accompanied by his nephew Sisir K. Bose, Bose gave

his watchers the slip and journeyed to Peshawar. With the assistance of

the Abwehr, he made his way to Peshawar where he was met at Peshawar

Cantonment station by Akbar Shah, Mohammed Shah and Bhagat Ram Talwar.

Bose was taken to the home of Abad Khan, a trusted friend of Akbar

Shah's. On 26 January 1941, Bose began his journey to reach Russia

through India's North West frontier with Afghanistan. For this reason,

he enlisted the help of Mian Akbar Shah, then a Forward Bloc leader in

the North-West Frontier Province. Shah had been out of India en route

to the Soviet Union, and suggested a novel disguise for Bose to assume.

Since Bose could not speak one word of Pashto, it would make him an

easy target of Pashto speakers working for the British. For this

reason, Shah suggested that Bose act deaf and dumb, and let his beard

grow to mimic those of the tribesmen. Supporters

of the Aga Khan helped him across the border into Afghanistan where he

was met by an Abwehr unit posing as a party of road construction

engineers from the Organization Todt who then aided his passage across

Afghanistan via Kabul to the border with Soviet Russia. Once in Russia

the NKVD transported Bose to Moscow where he hoped that Russia's

traditional enmity to British rule in India would result in support for

his plans for a popular rising in India. However, Bose found the

Soviets' response disappointing and was rapidly passed over to the

German Ambassador in Moscow, Count von der Schulenburg. He had Bose

flown on to Berlin in a special courier aircraft at the beginning of

April where he was to receive a more favourable hearing from Joachim

von Ribbentrop and the Foreign Ministry officials at the

Wilhelmstrasse. In

1941, when the British learned that Bose had sought the support of the

Axis Powers, they ordered their agents to intercept and assassinate

Bose before he reached Germany. A recently declassified intelligence

document refers to a top-secret instruction to the Special Operations

Executive (SOE) of British intelligence department to murder Bose. In

fact, the plan to liquidate Bose has few known parallels, and appears

to be a last desperate measure against a man who had thrown the British

Empire into a panic. Having escaped incarceration at home by

assuming the guise of a Pashtun insurance agent ("Ziaudddin") to reach

Afghanistan, Bose travelled to Moscow on the passport of an Italian

nobleman "Count Orlando Mazzotta". From Moscow, he reached Rome, and

from there he travelled to Germany, where he instituted the Special

Bureau for India under Adam von Trott zu Solz, broadcasting on the

German sponsored Azad Hind Radio. He founded the Free India Centre in

Berlin, and created the Indian Legion (consisting of some 4500

soldiers) out of Indian prisoners of war who had previously fought for

the British in North Africa prior to their capture by Axis forces. The

Indian Legion was attached to the Wehrmacht, and later transferred to

the Waffen SS. Its members swore the following allegiance to Hitler

and Bose: "I swear by God this holy oath that I will obey the leader of

the German race and state, Adolf Hitler, as the commander of the German

armed forces in the fight for India, whose leader is Subhas Chandra

Bose". This oath clearly abrogates control of the Indian legion to

the German armed forces whilst stating Bose's overall leadership of

India. He was also, however, prepared to envisage an invasion of India

via the U.S.S.R. by Nazi troops, spearheaded by the Azad Hind Legion;

many have questioned his judgment here, as it seems unlikely that the

Germans could have been easily persuaded to leave after such an

invasion, which might also have resulted in an Axis victory in the

War. The

lack of interest shown by Hitler in the cause of Indian independence

eventually caused Bose to become disillusioned with Hitler and he

decided to leave Nazi Germany in 1943. Bose had been living together

with his wife Emilie Schenkl in Berlin from 1941 until 1943, when he

left for south-east Asia. He travelled by the German submarine U-180

around the Cape of Good Hope to Imperial Japan (via Japanese submarine

I-29). Thereafter the Japanese helped him raise his army in Singapore.

This was the only civilian transfer across two submarines of two

different navies in World War II. The Indian National Army (INA) was

originally

founded by Capt Mohan Singh in Singapore in September 1942 with Japan's

Indian POWs in the Far East. This was along the concept of — and with

support of — what was then known as the Indian Independence League,

headed by expatriate nationalist leader Rash Behari Bose. The first INA

was however disbanded in December 1942 after disagreements between the

Hikari Kikan and Mohan Singh, who came to believe that the Japanese

High Command was using the INA as a mere pawn and Propaganda tool.

Mohan Singh was taken into custody and the troops returned to the

Prisoner of War camp. However, the idea of a liberation army was

revived with the arrival of Subhas Chandra Bose in the Far East in

1943. In July, at a meeting in Singapore, Rash Behari Bose handed over

control of the organisation to Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose was able to

reorganise the fledging army and organise massive support among the

expatriate Indian population in south-east Asia, who lent their support

by both enlisting in the Indian National Army, as well as financially

in response to Bose's calls for sacrifice for the national cause. At

its height it consisted of some 85,000 regular troops,

including a separate women's unit, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment (named

after Rani Lakshmi Bai) headed by Capt. Laxmi Vishwananthan, which is

seen as a first of its kind in Asia. Even

when faced with military reverses, Bose was able to maintain support

for the Azad Hind movement. Spoken as a part of a motivational speech

for the Indian National Army at a rally of Indians in Burma on July 4,

1944, Bose's most famous quote was "Give me blood, and I shall give you

freedom!" . In this, he urged the people of India to join him in his

fight against the British Raj. Spoken in Hindi, Bose's words are highly

evocative. The troops of the INA were under the aegis of a provisional

government, the Azad Hind Government, which came to produce its own

currency, postage stamps, court and civil code, and was recognised by

nine Axis states — Germany, Japan, Italy, the Independent State of

Croatia, Wang Jingwei's Government in Nanjing, Thailand, a provisional

government of Burma, Manchukuo and Japanese controlled Philippines.

Recent researches have shown that the USSR too had recognised the

"Provisional Government of Free India". Of those countries, five were

authorities established under Axis occupation. This government

participated in the so-called Greater East Asia Conference as a observer in November 1943. The

INA's first commitment was in the Japanese thrust towards Eastern

Indian frontiers of Manipur. INA's special forces, the Bahadur Group,

were extensively involved in operations behind enemy lines both during

the diversionary attacks in Arakan, as well as the Japanese thrust

towards Imphal and Kohima, along with the Burmese National Army led by

Ba Maw and Aung San. A year after the islands were taken by the

Japanese, the Provisional Government and the INA were established in

the Andaman and Nicobar Islands with Lt Col. A.D. Loganathan appointed

its Governor General. The islands were renamed Shaheed (Martyr) and

Swaraj (Self-rule). However, the Japanese Navy remained in essential

control of the island's administration. During Bose's only visit to the

islands in late in 1943, when he was carefully screened from the local

population by the Japanese authorities, who at that time were torturing

the leader of the Indian Independence League on the Islands, Dr. Diwan

Singh (who later died of his injuries, in the Cellular Jail). The

islanders made several attempts to alert Bose to their plight, but

apparently without success. Enraged with the lack of administrative

control, Lt. Col Loganathan later relinquished his authority to return

to the Government's head quarters in Rangoon. On

the Indian mainland, an Indian Tricolour, modelled after that of the

Indian National Congress, was raised for the first time in the town in

Moirang, in Manipur, in north-eastern India. The towns of Kohima and

Imphal were placed under siege by divisions of the Japanese, Burmese

and the Gandhi and Nehru Brigades of I.N.A. during the attempted

invasion of India, also known as Operation U-GO. However, Commonwealth

forces held both positions and then counter-attacked, in the process

inflicting serious losses on the besieging forces, which were then

forced to retreat back into Burma. Bose

had hoped that large numbers of soldiers would desert from the Indian

Army when they would discover that INA soldiers were attacking British

India from the outside. However, this did not materialise on a

sufficient scale. Instead, as the war situation worsened for the

Japanese, troops began to desert from the INA. At the same time

Japanese funding for the army diminished, and Bose was forced to raise

taxes on the Indian populations of Malaysia and Singapore, sometimes

extracting money by force. When the Japanese were defeated at the

battles of Kohima and Imphal, the Provisional Government's aim of

establishing a base in mainland India was lost forever. The INA was

forced to pull back, along with the retreating Japanese army, and

fought in key battles against the British Indian Army in its Burma

campaign, notable in Meiktilla, Mandalay, Pegu, Nyangyu and Mount Popa.

However, with the fall of Rangoon, Bose's government ceased be an

effective political entitiy. A large proportion of the INA troops

surrendered under Lt Col Loganathan when Rangoon fell. The remaining

troops retreated with Bose towards Malaya or made for Thailand. Japan's

surrender at the end of the war also led to the eventual surrender of

the Indian National Army, when the troops of the British Indian Army

were repatriated to India and some tried for treason. In a speech broadcast by the Azad Hind Radio from Singapore on July 6, 1944, Bose addressed Mahatma Gandhi as the "Father of the Nation". This was the first time that Mahatma Gandhi was referred to by this appellation. His

other famous quote was, "Chalo Delhi", meaning "On to Delhi!". This was

the call he used to give the INA armies to motivate them. "Jai Hind",

or, "Glory to India!" was another slogan used by him and later adopted

by the Government of India and the Indian Armed Forces.

Bose is alleged to have died in a plane crash over Taiwan, while flying to Tokyo on 18 August 1945. It is believed that he was en route to the Soviet Union in a Japanese plane when it crashed in Taiwan,

burning him fatally. However, his body was never recovered, and many

theories have been put forward concerning his possible survival. One

such claim is that Bose actually died later in Siberia, while in Soviet captivity. Several committees have been set up by the Government of India to probe

into this matter. In May 1956, a four-man Indian team (known as the

Shah Nawaz Committee) visited Japan to

probe the circumstances of Bose's alleged death. However, the Indian

government did not then request assistance from the government of Taiwan in the matter, citing their lack of diplomatic relations with Taiwan. However, the Inquiry Commission under Justice Mukherjee,

which investigated the Bose disappearance mystery in the period

1999 - 2005, did approach the Taiwanese government, and obtained

information from the Taiwan Government that no plane carrying Bose had

ever crashed in Taipei, and there was, in fact, no plane crash in

Taiwan on 18 August 1945 as alleged. The Mukherjee Commission also received a report originating from the U.S. Department of State supporting the claim of the Taiwan Government that no such air crash took place during that time frame. The

Justice Mukherjee Commission of Inquiry submitted its report to the

Indian Government on November 8, 2005. The report was tabled in

Parliament on May 17, 2006. The probe said in its report that as Bose

did not die in the plane crash, and that the ashes at the Renkoji

Temple (said to be of Bose's) are not his. However, the Indian

Government rejected the findings of the Commission, though no reasons

were cited. Several

documents which could perhaps provide lead to the disappearance of Bose

have not been declassified by the Government of India, the reason cited

being publication of these documents could sour India's relations with

some other countries.

Bose was posthumously awarded the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award in 1992, but it was later withdrawn in response to a Supreme Court directive

following a Public Interest Litigation filed in the Court against the

"posthumous" nature of the award. The Award Committee could not give

conclusive evidence on Bose's death and thus the "posthumous" award was

invalidated. No headway was made on this issue however. Bose's portrait hangs in the Indian Parliament, and a statue of him has been erected in front of the West Bengal Legislative Assembly.

Several people believed that the Hindu sanyasi named Bhagwanji or 'Gumnami Baba', who lived in the house Ram Bhawan in Faizabad, UP at

least until 1985, was Subhas Chandra Bose in exile. There had been at

least four known occasions when Gumnami Baba reportedly claimed he was

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. The

belongings of the sanyasi were taken into custody after his death,

following a court order. These were later subjected to inspection by the Justice Mukherjee Commission of Inquiry. The commission came down against this belief, in the absence of any "clinching evidence". The independent probe done by the Hindustan Times into the case however provided hints that the monk was Bose himself. Some

people believe that Gumnami Baba died on 16 September 1985, while some

dispute this. The story of Gumnami Baba came to light on his death. It

is alleged that he was cremated in the dead of night, just under the

light of a motorcycle's headlamp, at Faizabad's popular picnic spot, on

the bank of River Saryu. His face distorted by acid to protect his

identity. Faizabad's Bengali community still pays homage at the

memorial built at his cremation site on the anniversary of his birth.

However, the life and activities of Bhagwanji remain a mystery even

today. Justice

Manoj Kumar Mukherjee who probed into the disappearance of Netaji

Subhas Chandra Bose stated in his report that the sanyasi of Faizabad (Bhagwanji)

was not Bose as there was no clinching evidence to prove it. However,

he inadvertently stated in a documentary shoot that he believed

Bhagwanji was none other than Bose. This revelation supports the view that Bose had not died in the plane crash in 1945, and was in fact in India after that.